"The Business of Strangers" belongs to a genre of films that usually make me feel like I'm waiting to take a beating. In this type of picture, the audience, kept at a deliberate remove from the characters, is invited to observe them as if they were bugs under glass, and the head games and power plays they indulge in are like the behavior of some inferior species. It's like some sadistic encounter session where the objective is "truth telling": In other words, the moment when all niceties break down and the characters are at their ugliest.

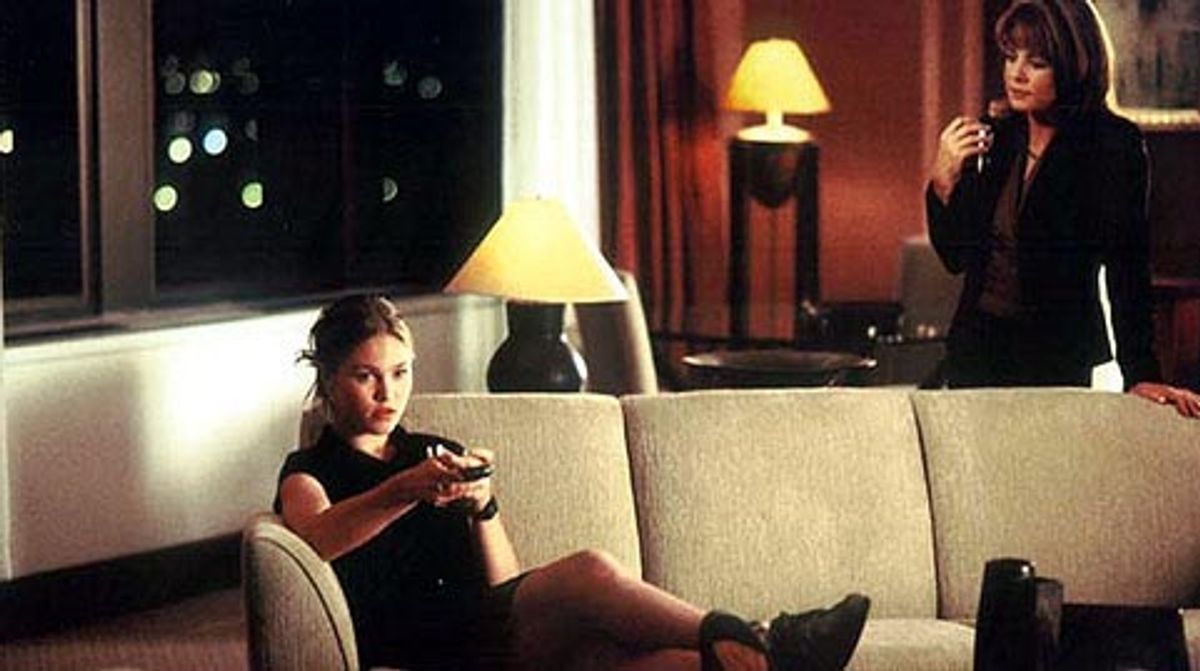

Watching "The Business of Strangers" you know that it's only a matter of time before the barely disguised hostility between the two characters -- a successful businesswoman (Stockard Channing) and her young, punkish assistant (Julia Stiles) -- results in emotional freakout. The movie has been described as a female "In the Company of Men" (and there must be at least -- what? -- four people longing to see that).

The faint praise I can offer "The Business of Strangers" is that the writer/director, Patrick Stettner, making his feature debut, shows a smidgen more humanity than is typical for this type of movie. Part of his plan is to reverse our initial reactions to both characters, and in the process he shows Stockard Channing's character more empathy than businesspeople usually get in the movies. (There are some solid reasons why moviemakers and writers show such a lack of interest in the inner workings of corporate characters -- namely the lack of interest corporations seem to have in the rest of us.) A good part of that empathy is due entirely to his two lead actors, who put recognizable flesh on Stettner's programmatic conceptions of his characters.

The setup for any head-game movie is to bring the characters together and isolate them. The beginning of the cat-and-cat game of "The Business of Strangers" is an important out-of-town presentation that Julie Styron (Channing), a driven corporate vice president, is sent to make. On the way, Julie gets word from her secretary (who is as much her spy and confidant and confessor as her gal Friday) about some secret executive meeting of which she hasn't been told and which she's sure can only mean she's fired. After arranging to fly out a corporate headhunter (Frederick Weller) to plan her next move, Julie shows up for the presentation but finds that Paula (Julia Stiles), the young assistant in charge of the audio-visual part of her dog-and-pony show, has not turned up. Paula rushes in at the end of the meeting (her plane had been delayed), but not soon enough to prevent Julie from firing her. Shortly after, Julie finds out that she was reading her company's maneuverings all wrong: She is not going to be fired, but has been offered the position of CEO. Celebrating with a drink in the lounge of her airport hotel, Julie sees Paula sitting alone and buys her a drink. What follows is a predictable, higher stakes version of truth or dare.

Stettner does everything he can to set the stage for what follows. No matter what you think of it, there's no denying that "The Business of Strangers" has been carefully and fully conceived. The look of the movie, shot by Teo Maniaci, is perfect, if off-putting. It's a cold assemblage of hard edges; even the functional furniture doesn't promise anything in the way of comfort. The offices where Julie works are all glass and chrome. Meeting in them, she and the other execs seem both exposed and cocooned. The hotel restaurant where her boss delivers the news of her promotion is so vast and unpopulated that their table might as well be in the middle of a runway. We're never told what Julie's business is, or where this meeting is taking place. This works to the movie's advantage. The locale of the movie is a "virtual" corporate world of limos and office parks and anonymous hotels catering to business travelers. It's both nowhere and everywhere.

"The Business of Strangers" is very much about how corporate jobs become both all-consuming and alienating -- the only person Julie seems at all close to is her secretary and even that's an impersonal connection, tethered as they are by cellphone. But the movie is alienating, too. Stettner is such a precise filmmaker that his technique isn't just a reflection of Julie's rigidly ordered world (she unpacks in her hotel room as if on autopilot, finding the proper place for each piece of clothing, each accessory), it's a sign of his own rigidity.

At 83 minutes the movie is without a wasted movement. But when you're dealing with material as narrow as Stettner is here, when your purpose isn't to enrich your characters but to break them down to their hard, frightened essences, that kind of whittling away exposes the shallowness of the movie even as it intensifies the meaning. Stettner directs as if a joke, or a stray shot included just for the beauty of it, or, hell, as if a flash of beauty would destroy his precious design. (There is one good deadpan throwaway gag: Julie making a call on her cellphone oblivious to the bank of pay phones next to her. It's like the gag in Bill Forsyth's "Gregory's Girl" where the hero, standing in front of a huge public clock he doesn't even notice, consults his wristwatch.) Even the scenes that take place at the highest emotional pitch feel as deliberate as Julie's presentation. Stettner's writing and direction is an example of the very control-freak approach he means to criticize.

But Channing and Stiles push at the bounds of that rigidity. Their performances are remarkable because they both make you feel as if you've encountered these people before. Along with Blythe Danner, Stockard Channing must be the best, least-used American actress in the movies. Luckily for both of them, they've had a great body of stage work. Movie audiences got a glimpse of that work when Channing reprised the unforgettable, high-style comic performance she gave on stage in John Guare's "Six Degrees of Separation" in Fred Schepisi's brilliant film of the play. She gets so few movie leading roles that it's a treat when she does, and she doesn't squander the opportunity here.

It's no small feat for an actor whose features are as open as hers -- big eyes, round cheeks, a downward-turned mouth that can seem both pouting and sardonic -- to turn that openness to the guarded tautness Channing does here. Even when she's seemingly not doing anything -- just standing in the shower as if the water could wash away the tensions knotted inside her, or reclining afterward in a bathrobe as she tries in vain to relax -- her skin seems to be working overtime, straining to hold in her frazzled nerves. Julie gets through her days on a combination of Zoloft, Valium and Dewar's, none of which seem to have much effect on her. It's sheer will that drives her on. The knowledge of everything she's given up to get where she has is never far from her mind, nor is the determination to make sure that those sacrifices weren't in vain.

Channing imbues every inflection, every precise movement with a sense of barely concealed panic. You hear it in the false cheeriness of her voice when she checks in with her secretary, or in the forced confidence of her presentation. It's as if she walks through life with a chip implanted in her brain playing the O'Jays' "Back Stabbers" on a repeating loop. So it's no surprise that she savors the moments when she can exercise power. There's more than a touch of condescension in the amusement she shows when she tries to make amends to Paula, and the young woman tests that friendliness, ordering the most expensive drink she can, not budging an inch in her resentment.

But then it's hard not to be amused by Paula. She's the essence of every young person of limited experience who's certain she knows everything there is to know about life. When she tells Julie that the job she's just lost was merely a money job, that she's really a writer, Julie asks her if she writes for Web zines, and she replies, "I'm pretty old-school. I've been published." That combination of arrogance and an utter lack of perspective is part of the reason you watch Stiles' Paula so warily. Stettner plays us, winning us immediately to her side (a young woman who loses her job through no fault of her own) while encouraging us to see Julie as a corporate ballbuster.

Of course, Stettner's scheme calls for the tables to be turned (and just how he does that requires divulging a spoiler). When Nick, the corporate headhunter, joins the women for a drink, Paula freezes. Alone with Julie, she explains that Nick, who doesn't recognize Paula, once raped a friend of hers at a frat party. Outraged, Julie says they should get back at him. Paula, indulging in self-pity as much as contempt for someone who thinks the world is fair, dismisses the idea. Men get away with these things all the time, she tells Julie. But when Nick shows up at Julie's suite, it's Paula who instigates a plan, and Julie, titillated at stepping outside of her respectable boundaries, plays along.

Stiles, who can play vulnerable, as she did in "Hamlet" and "Save the Last Dance," can also make her features frighteningly small and hard and unforgiving. It's as if all the resentment she feels has been translated into making her a stone monolith of judgment. Paula is a damaged brat, the kind who holds people at arm's length while she scrutinizes them, only to reveal a margin of vulnerability and then rebuff any attempt at consolation or intimacy. We've all seen Paula, in the crowd at rock clubs, working (or browsing) in a bookstore, sizing up whoever drifts into her sphere of self-protection, treating each human interaction as if it were an intrusion. And yet you can never quite dismiss her, never lose the feeling that she'll respond to some kindness, even as she exasperates you whenever you try to act decently toward her.

It's a booby-trapped role, offering both a pat psychological explanation for Paula's behavior, and ultimately casting her in the role of Pinteresque intruder, the enigma who sows chaos seemingly for the sheer hell of it. The movie is carefully designed so that we can look back and see every bit of her feistiness revealed as treachery. It's to Stiles' credit that she shows no instinct to soften the character, to play for the audience's sympathy. We are never sure whether to trust her, and Stiles is gutsy enough not to offer any assurances, to be more interested in burrowing into the character than giving a damn whether the audience likes her.

Julie's long night with Paula is meant to trigger her realization that what she's worked toward amounts to nothing. The contours that Channing works into the performance, particularly the repressed instinct for fun that Paula brings out in her, keep Julie's fate from seeming her comeuppance. Julie's pride in what she's accomplished meshes with Channing's pride as an actress. She'll be damned if she allows someone else to make her feel small. It's that knife's edge of pride that allows Channing to overcome the limitations of the role. Julie is just as familiar as Paula. We've all had a boss like her, someone who hides her humanity behind a wall of corporate responsibility, afraid that acting like a person will make her less effective in her job. She's frustrating because of the humanity that comes out in sudden glimpses that she works so hard to hide most of the time.

Channing grounds the performance in just that hidden humanity. She subverts Stettner's tendencies to see a corporation woman as the other. She doesn't have to elucidate indignities and sacrifices she's made to get where she is. We can see them in the way she goes through her job as if striding onto the battlefield. Without losing her dignity, Channing scrapes away Julie's protective veneer, robbing us of the notion that successful businesspeople are immune to the slights all of us face every day.

It's not that either Channing or Stiles work against Stettner. It's just that they bring more to their roles than his constricting conception allows. And inadvertently, they expose his shortcomings. Stettner is unusually sure of himself for a first-time director, without showing much freedom or range. (Perhaps he's sure of himself because he doesn't show much freedom or range.) But "The Business of Strangers" suggests that he may have a talent for directing actors. He must be one of the luckiest and unluckiest debut directors in years, blessed with actors who both take the focus away from his limitations and wind up shining a spotlight on them.

Shares