The Indianapolis Vipers have just beaten the Alabama Slammers 44-8 on the muddy but not quite frozen tundra of the Arlington High School field, and fullback Jodi "Moose" Armstrong is talking about the state of women's professional football.

"There's the WAFL," she says, citing the league in which the Vipers, the Slammers and 14 other teams play. "There's the NWFL, there's the WSFL, there's the WFA, there's something else in the West, I forget what it's called. It's alphabet soup."

She's forgotten the IWFL, the WPFL, the LTFL and maybe a few others. But the point is: You probably didn't even know there was such a thing as women's professional tackle football, and if you talk to a woman professional tackle football player, she'll tell you the problem is there are too many teams, too many leagues. And if you ask her to explain how we got to this point, how the Women's American Football League, for example, came about, your head will soon be hurting like an offensive lineman who's spent a long afternoon getting helmet-slapped by Warren Sapp, who plays over in the men's league.

The WAFL is in its first season. It grew from the ashes of the Women's Professional Football League, though a remnant of that league still exists, with four teams and a spring schedule. The WPFL, in turn, grew out of a 1999 barnstorming tour of two teams, the Minnesota Vixens and the Lake Michigan Minx, who were formed for the purpose of the tour. (The Vixens-Minx enterprise was chronicled in a documentary called "True-Hearted Vixens," which aired on PBS over the summer.)

Moose, whose nickname comes not from her small-town Minnesota background but from her on-field resemblance to former Dallas Cowboys fullback Daryl "Moose" Johnston, is not only a running back for the Indianapolis Vipers, she is also the director of operations, as she puts it, for the Minneapolis Vixen, who used to be the Minnesota Vixens, and who aren't actually in the WAFL, but did play three exhibition games against WAFL teams that counted in the WAFL standings. The Vixen are sort of on hold, waiting for an infusion of cash, and hope to play in a league next year.

Have I lost you? Let's back up a little.

The Women's American Football League consists of 16 teams playing in five divisions coast to coast. The teams play tackle football in full pads, under NFL rules, during the fall. Six games into the 10-game season the undefeated Tampa Bay Force and the Vipers are shaping up as the contenders for the Atlantic Conference championship, and the powers in the Western Conference are the division-leading Seattle WarBirds, Sacramento Sirens and California Quake, along with the San Diego Sunfire. The conference champions will play in the World Women's Bowl championship game on Feb. 9.

The players, says Vipers coach K.C. Carter, come from all walks of life. "They're a range of women who come from all over," he says, "from Division I [in other sports] to your local housewife to a novelist who's watched football and has probably played pick-up games with her brothers."

Some of them have played flag football in organized leagues, and there are quite a few from the world of women's rugby. But tackle football experience is rare. There have been attempts at women's pro football leagues since the '60s, and the original National Women's Football League formed in 1974. Who can forget the Oklahoma City Dolls, the Toledo Troopers, the Los Angeles Dandelions? But the league began to falter in the late '70s and eventually disappeared, and no league since has reached even its modest level of success. (A 1981 TV movie called "The Oklahoma City Dolls," starring Susan Blakely and Eddie Albert, was not about the real Dolls team.)

Dana Miller, a 35-year-old physical therapist and the Vipers' starting quarterback, ticks off her athletic background: basketball, softball, volleyball, track, karate, kickboxing, boxing. She says she was the first female Golden Gloves champion in Indiana, at 156 pounds. "Just a lot of contact sport stuff," she says. "I've always really been into it. I of course played in the yard a lot with all the neighborhood boys."

Miller heard about tryouts for the new league from teammates on a summer softball team.

"I told Coach, I've been dreaming about this kind of opportunity since I was probably 6 years old, but athletics like that, for girls, was just unheard of," she says. "It's like a high, just being out here and playing football, something I never thought I'd be able to do."

The Vipers practice three nights a week at an Indianapolis park. On the night before Saturday's Slammers game, assistant coach Cedric Markes is leading the various units in a walk-through as head coach Carter tries to jury-rig Miller's helmet with a one-way walkie-talkie device so he can relay plays to her from the sidelines during the game without resorting to hand signals or courier players. He tapes the receiver into the helmet, then has her put it on and walk about 50 yards away. "If you can hear me, raise your hand," he says into the microphone several times. She finally does give a little wave. She jogs back and reports that the speaker's digging into her ear. "If I get hit it's gonna take my ear off," she says matter-of-factly.

Carter says he'll work on it some more. He'll have time. "If I get to bed before 4 the night before a game, I'm in trouble," he laughs.

Carter is 36 years old and a Marion County special deputy sheriff. After an injury kept him from competing for a roster spot at Indiana State, he played semipro football for 11 years as a wide receiver. "My wife made me retire," he says. He's coached from youth leagues on up to semipro. He saw an article about the barnstorming tour and began making inquiries, eventually becoming involved with the new WAFL after talking to the league's founder, Carter Turner.

He says coaching women is a lot like coaching men. "When I'm talking to the ladies out here, I'm pretty much talking to them like I'm talking to guys," Carter says. "If they mess up I jump on their butt just like you would any other athlete, and at the same time I'll build them up and pat 'em on the back when they do something right. When you're on this field you're an athlete. Male, female. Don't matter."

Game day dawns cold and cloudy. Several days of rain have left the field muddy. The Vipers, in their black uniforms with green trim, do calisthenics in the west end zone. In the muck of the east end zone, assistant coach Brian Watson leads the Alabama Slammers, in red and white uniforms, through their drills. He tells them to get down in the mud for stretching.

"We're gonna wallow in it," Watson bellows. "We're from Alabama! We know what mud is!" As they hold a stretch he asks his players, "Is it burning yet?" One of them yells back, "It's squishing!"

But despite the levity, this is going to be a long day for the Slammers. They've come north with only 14 players.

"It's tough, they have to play both sides of the football," Watson says. "But they've got heart. That's all you need." Watson is here because he was asked to help out as an assistant by his wife, Mandi, an offensive tackle, and by head coach Mark Leslie, a soft-spoken youth league coach. Though the league envisioned a team in Birmingham, the Slammers split their games between Birmingham and Huntsville, and they've been drawing poorly, fewer than 500 fans a game. They have one win in their first five contests, and they've already taken a beating from Indianapolis, 52-6.

The Vipers are 3-2, including a forfeit win over the Jacksonville Dixie Blues, who didn't make their trip north, the sanction for which is that they will also forfeit their scheduled home game against Indianapolis. The Vipers figure to win the Atlantic Conference's Central Division unless the New Orleans Voodoo Dolls go on a major hot streak.

Having to send the same players out on both offense and defense against the Vipers, who have dressed 32 and play in platoons, the Slammers pretty much have no chance.

"Basically we just tell the players to pace themselves, try not to do more than they would normally do," Leslie says softly. "Just play the game."

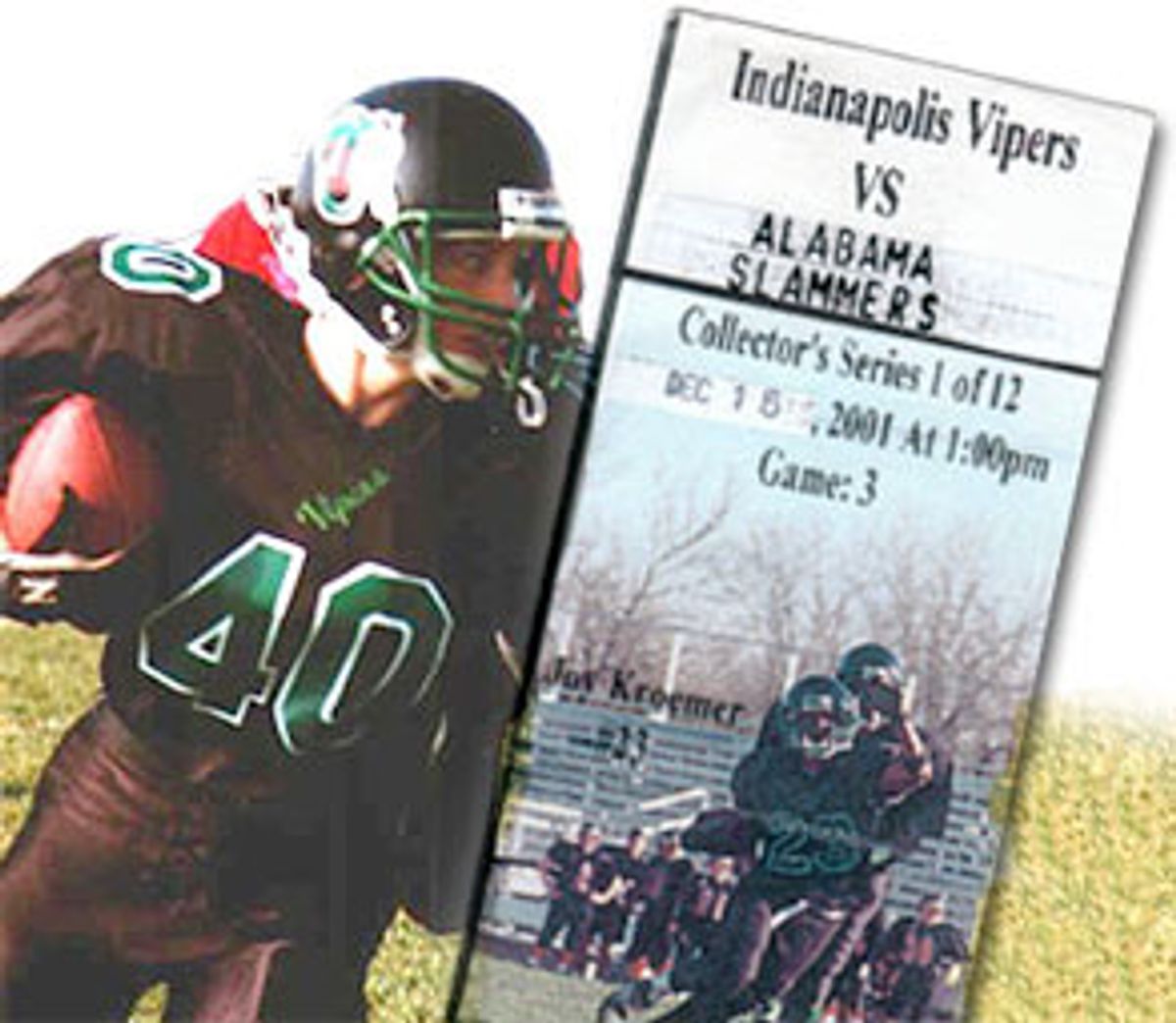

The Vipers' marquee player is Joy Kroemer, who was a member of the first professional women's baseball team, the barnstorming Colorado Silver Bullets. Kroemer is a cornerback, though she also sometimes plays in the offensive backfield. The Slammers mostly avoid her, rarely even lining up a wide receiver on her side of the field, but she still manages to intercept a pass and make seven tackles, including a textbook, bone-crunching hit that stops a ball-carrier at the line of scrimmage late in the game.

Though the talent level varies from world-class athletes like Kroemer or Tampa Bay's Sabrina Kelly, whom Carter calls "the Walter Payton/Barry Sanders of our league," to women who cannot be mistaken for athletes at all, they produce pretty good football.

"I think the quality of play has gone up every week," says Chuck Townsend, the referee for the Slammers-Vipers game. "I just think that once this catches on, more and more people get involved, the talent level will increase, but it's exciting football. I think it's on a par with high school football. Maybe a little better than that. Some aspects yes and some aspects no."

Townsend leads a five-man crew that officiates high school games. They pick up another two to form an NFL-style seven-man crew for work in WAFL games, for which they're paid expenses. "We do it because we love the game. It extends our high school season," he says. I ask him if officiating women is different than officiating for men.

"The ladies seem to have a different demeanor about them out there," he says. "They seem to be more helping each other along. It's more cutthroat with the guys. [In their first game against Indianapolis] Alabama came down here and scored a touchdown. It was their first touchdown of the year. The Alabama team was thrilled, but I think even the Indianapolis team was thrilled. They were up by 40 points, you know. It wasn't that they tried to let 'em in, but they were like, 'Good job, you guys got a touchdown,' where guys would have been, 'Daggone, we actually let 'em score.'"

That difference is evident during the game. Players help each other to their feet more often then men do, and when receivers and defensive backs jaw at each other, they're not talking smack. They just seem to be joking around a little, enjoying their time together on the field.

The Slammers put up some resistance. It's not easy for the Vipers, but things are going their way. Coach Carter speaks into the microphone that relays the plays to Miller's helmet speaker, saying things incomprehensible to nonfootball people, things like, "Seven, stay-five-stay." At one point, the system breaks down. Miller holds her hands out, palms up. She can't hear him. Carter shouts to her, "Seven, five, zero." She goes back to the huddle, brings the team to the line, drops back to pass and hits wide receiver Virginia Hicks in stride for a 48-yard touchdown and a 12-0 lead. It's the first of Hicks' four TD catches of the day, the second of a league-record six touchdown passes for Miller. That kind of day.

At halftime, Indianapolis leads 24-0. The Vipers are standing around outside their locker room, which is locked for the moment, as the 14 Slammers trudge by on the way to theirs. The Vipers players make an alley for them. As the Slammers walk through, each one gets a series of encouraging slaps on the shoulder pads from their opponents. "Good job, ladies," the Vipers players tell them. The players all refer to each other as ladies or girls.

The second half is more of the same, with Indianapolis scoring three more touchdowns -- and their only successful two-point conversion; the kicking game is one of those aspects that seems to be lacking -- and Alabama getting into the end zone once, for the final score of 44-8. The Vipers attracted about 3,000 fans for their opening game, and have since had crowds of about 1,000, but on this chilly late fall day there are only about 120 people in the stands, mostly friends and family of the players and coaches. In the fourth quarter they get on the officials for throwing too many flags and on the hometown team for throwing too many passes, both of which extend the game, and their shivering.

"It's a little discouraging," receiving star Hicks says about the small crowd, "but you know, the die-hards are out here."

Hicks, 30, is a veteran of four years of flag football. Though she's a bit of a joker off the field, she's also an upbeat team leader and one of the Vipers' best players. I ask her if she thinks the WAFL can succeed, a term defined in the league's promotional materials as reaching the level of the WNBA, the women's pro basketball league, which has backing from the NBA.

"I definitely think we can get to that level," she says, "especially if we can get the NFL to back us at some point in time. I know lots of people who, next year when we have tryouts, they're like, 'I'm there.' Since people have heard about it now, we have a lot more people interested in it. I think if we can continue to get the fans involved and get the community involved, it's definitely going to succeed."

That sentiment is echoed by the league's founder, Carter Turner, in Daytona Beach, Fla. Turner promoted the 1999 barnstorming tour. "That developed into the WPFL. We played a limited season there. We got about halfway through that season." Then, he says, "What they call 'fraudulent investors' came in."

"The funny thing about women's football is that it's attracted about 99 percent really good people, but it has attracted some people who think they can make fast, easy money off of women and football, and that's what happened in the WPFL," he says.

Catherine Masters, who runs an entertainment marketing company in Nashville, spun off a new NWFL, which plays in the spring. The Philadelphia Liberty Belles are the current champions, and there are 21 teams set to play in 2002, all of them east of the Mississippi.

Turner, 48, who has a master's degree in sports administration and has worked in both women's and men's sports on the college and pro level for many years, decided to stick with an autumn schedule for the nationwide WAFL.

"We feel that playing traditional fall football, for traditional reasons as well as health reasons, is the way to go," he says. And this is the time of year, he says, when it pays off. "Our window of opportunity, we felt, was when college and high school football wound down, and the only football programming available now is the NFL and us."

Turner says the difference between last year's WPFL and the WAFL is that the former had a centralized structure, with one investor setting up all the teams and taking the lion's share of the profits. That didn't work out, he says, because first one investor and then a second "never performed." So he decided the WAFL would be decentralized, with the teams responsible for their own outfitting, upkeep and travel, and keeping any profits. "That's worked out really well."

It hasn't been without a few bumps. Turner cites San Diego as the attendance leader, with crowds of up to 5,000 people, with Sacramento and Oakland not far behind. But there are teams that aren't drawing well, and there was some fractiousness in late October when Turner, who is listed as the director of league operations and media relations, fired commissioner Cindi Dwyer. "Not only has Ms. Dwyer failed to achieve any of the goals and objectives for which she was brought on board," read an unsigned league statement, "but she has contributed negatively with actions detrimental to the welfare of the league and has actively sabotaged business operations of the league while promoting discontent amongst member teams with false information." The statement said that no legal action would be taken. Asked if there was wrongdoing, Turner says no.

Dwyer couldn't be reached for comment.

Turner also says, "We don't say disparaging things about other leagues because they're all pushing women's football forward in their own way," but he feels the WAFL, with its fall schedule and nationwide, decentralized structure, is the best of them.

"History's repeating itself. Back in the '70s, the old NWFL had the same problem, where they split into several different leagues and, well, the country really just wasn't ready for women playing full contact sports back then," Turner says. "But the same thing has happened now where people have come along who say they can do it better or have a better way to do it, and we've stayed the course and been pretty much successful throughout."

Turner also insists the WAFL has the best talent. "We're getting the top athletes, and that's what we're touting ourselves as, the top professional league," he says. It should be noted that the term "professional" is thrown around loosely in the world of women's football. No one draws a salary, and WAFL players will get paid only if there's profit left over at the end of the season. Turner says that's likely for any team that can pull in more than 1,000 or so fans a game, but it doesn't figure to translate into anything like a living wage. The women are required to have jobs and their own health insurance in order to play.

The world does seem to be ready for women to play football, though. While local media has for the most part ignored the games, the coaches and players I talk to all say that response to the new league has been positive, both in the scant media coverage and just around town. "You know, we don't hear a lot of the negative parts, people saying, well, women shouldn't be playing football," Carter says. "We probably heard that maybe when we first started, but we don't hear that anymore. Everybody says, 'Man, women playing football. That's cool.'"

Boo Hunter, an offensive lineman for the California Quake in Long Beach, is the unofficial online chronicler of women's pro football at her Unofficial Guide to Women's Pro Football site. Though she plays in the WAFL, Hunter says, via e-mail, that while the NWFL "may be growing too fast, adding 11 new teams for 2002 ... if they pull off another successful season, they will have established themselves as the premiere women's football league." Hunter, like Turner, dismisses the various other leagues as having "not really played serious league games."

Jodi Armstrong -- "Moose," the Vixen official and Vipers fullback -- has been part of this adventure for three years. As much as she loves the game, this longtime St. Paul Pioneer Press copy editor is realistic about what she's seen.

"There's more women playing, there's better athletes being attracted, but as far as the overarching: We need some national unity, we need a major financial backer, we need some corporate sponsors to take us seriously," she says.

As for all the competing leagues, "They all believe their management system is going to win out in the end and they're so frustrated with each other that they won't talk to each other, which is what has to happen if we're going to be nationally successful," she says. "The Nikes and the Reeboks and the people who we need to have behind us in order to have people at the NFL take us seriously, I just worry that they look at us and think, 'Huh, no way.' Too bush, too fractured, too, just, risky. I mean, you saw the game. We're not putting on bad football. We're just not making sure that we crawl before we walk."

While Turner insists, "We feel we're just right on the edge now of the big sponsors coming in," Armstrong says, "Carter Turner could sell ice cream to Eskimos," and expresses some misgivings about Turner's ability to lead the league to success.

I ask Armstrong why she's involved.

"I think that even if this is going to run into the ground, for as long as it lasts, it deserves to be given every chance to be legitimate," she says. "And there are some bright spots. The West Coast teams in the WAFL are going strong. I mean, there are bright spots, and I want Minnesota to be one of the bright spots, and we are one of the charter members of this whole frickin' thing, and to let us fall by the wayside is, I think, in some ways, to admit defeat, and I'm just a stubborn Minnesotan who doesn't -- I will not go down without a fight."

Back on the muddy field at Arlington High School, after the players had congratulated each other and made arrangements to meet at a local chicken wing joint, an exhausted Dana Sanders, Alabama Slammers quarterback/defensive back, assesses her afternoon.

"Very long game," she says. "We had a few girls couldn't make it because of their jobs and different things like that, childcare, so we're a little bit short-handed. We were playing with 15."

Actually, 14. I ask her the same question I'd asked Armstrong. Why stay with it?

"Oh, I love it," she says, still panting from her efforts. "I love playing. If we have 15 or 50, I still love it."

Shares