This Dec. 27, Marlene Dietrich would have been 100. It's entirely provable that she died, in 1992 in Paris, in the Avenue Montaigne apartment she had retreated to, because she preferred not to be seen or photographed anymore. There's a death certificate. They took the body back to Berlin and buried it. There are witnesses, and so on. But you don't have to believe anything you don't want to. She may be dealing the cards still in some small cantina on the Mexican border, with the chili pot alive and warm in the tiny kitchen. That woman, Tanya, had a wisdom and fatalism -- not to mention the sex appeal -- that could have suited 1,000 as easily as 100.

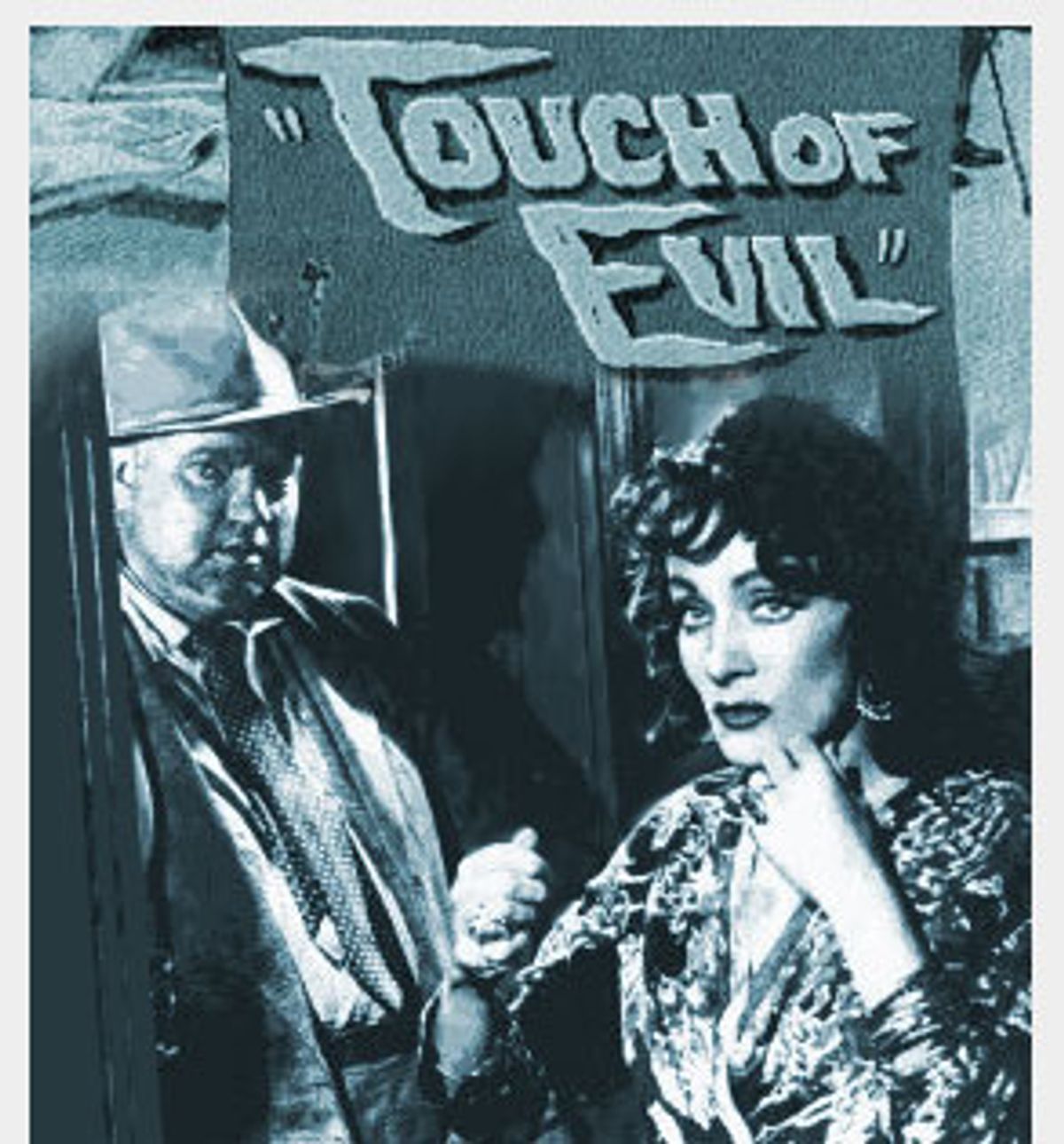

Tanya, you may recall, is the character Dietrich played for Orson Welles in "Touch of Evil." That was 1957, when they filmed it at Universal. Her movie career was largely over by then. She was more famous as a nightclub performer and just for being "Marlene Dietrich," the woman Josef von Sternberg had found in Berlin and cast in "The Blue Angel." This was the woman he had brought back to America, where they'd made six more great films together about the impossibility and the absurdity of enduring romance. They'd been lovers, yes, but she never bothered to get a divorce from her husband, and certainly never stopped taking any sexual opportunity that came into view. "I can't help it," was one of the things she sang, and you understood that it ruled out anything like fidelity. And in the early 1930s, the attitude had been far too unsentimental for the American audience. The films with von Sternberg ran out of audience. His career was finished and she was called box office poison.

But she was and always will be the supreme image of the femme fatale, holding her face straight, severe and beautiful so as not to break out laughing at the idiocy, the feebleness and the hopefulness that still, somehow, lingers in men.

And she knew Orson. During the war, in Los Angeles, in a tent on Cahuenga Boulevard, they had done a show together where he was the magician who sawed her in two and then brought the divine parts together again, properly aligned. What a film that could have been, for Buñuel, say -- the adoring magician who can enjoy the lower or the upper half of his beloved (each has its charms and flavors), but who has forgotten the word that reunites them.

Anyway, on "Touch of Evil," after they had started shooting, Welles called up his old pal. He asked her to find the dark wig she had worn once in a very silly film called "Golden Earrings." He threw together a cheap cantina set, adding a pianola that keeps playing sad, romantic songs. He gave her cigarillos to smoke, and for a moment his own character -- the crooked, bloated border cop Hank Quinlan -- stumbles into the cantina and sees some kind of past.

"Have you forgotten your old friend?" he asks.

She looks more closely with those pitiless eyes and tells him, "You're a mess, honey." So he was, padded up to a size that Orson himself would attain in later years -- a size so grisly you have to wonder how any man that gross could actually have conventional sexual relations. So he might dream of having the separated parts of his goddess, nimble enough to play in the air above him.

That scene in "Touch of Evil" is camp, of course, with its barbed double meanings about the glory that once was Orson and Marlene and the different ways time and chili had treated them both. At the same time, it's a perfect summation of the kind of woman von Sternberg had created with Marlene -- the femme fatale, the beautiful woman who will be an angel of death for her stupid men.

People seldom notice the other meaning in "femme fatale" -- that the woman is dying, too, getting older, losing that youth that is so often the engine of desire and desirability. The femme fatale in so much film noir is a creature made to torture the adolescent self-pity of the guy. Whereas, in Dietrich's real life, in her songs sometimes, she faced the universal tragedy of adult life -- that we all grow older, less lovely and hopeful. We can't help it. What does it matter what else you say about people?

Shares