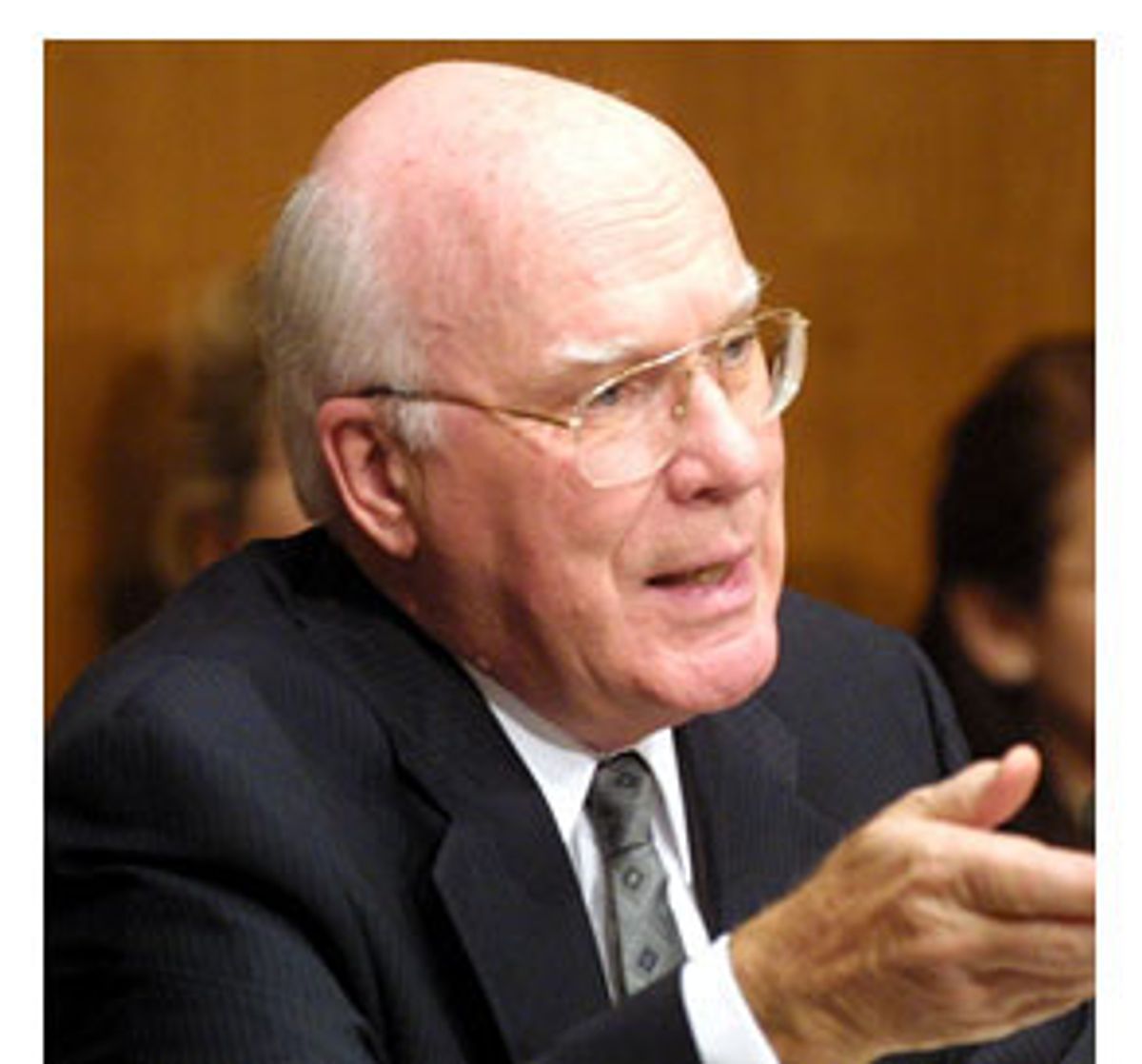

Elected Chittenden County state's attorney at 26, born-and-bred Vermonter Patrick Leahy was first elected to the Senate in 1974 with 49 percent of the vote. He was only 34 -- the second youngest in the Senate. Over the next quarter-century, the Georgetown Law School graduate moved from the status of prematurely bald whipper-snapper to senior Democrat, cruising to increasingly easy re-election victories -- in 1998 he defeated obscure cult-film hero Fred Tuttle, 72 percent to 22 percent.

While his politics are generally old-school liberal in the Kennedy-Humphrey tradition, Leahy is often willing to let his eccentric Vermontness come out, whether through dry wit or professions of his love for the Grateful Dead and Batman. (Leahy had a bit part in 1997's abysmal "Batman & Robin"; he provided the voice of the governor of the Arizona territory in an episode of "Batman: the Animated Series," and wrote the foreword for the 1992 collection "Batman: the Dark Knight Archives.")

The more seriously-channeled energies of the so-called "Cyber-Senator" have been spent in support of foreign aid programs and in defense of civil liberties and privacy rights. He led the charge against both land mines and the death penalty, long before either cause became trendy.

With the defection of one-time rival and state junior Senator Jim Jeffords from the GOP in June, which handed the Democrats control of the Senate, Leahy jumped to the chairmanship of the powerful and high-profile Judiciary Committee. Even before then, as ranking Democrat on the committee, Leahy caused the Bush White House consternation by objecting to his nominee for attorney general -- his former colleague from Missouri, defeated Sen. John Ashcroft -- and holding up the nomination of Ted Olson as solicitor general.

In the post-Sept. 11 era, Leahy has emerged as perhaps the biggest obstacle to the sweeping law-enforcement powers sought by the Bush Administration and Attorney General John Ashcroft. After President Bush's Sept. 20 address to a joint session of Congress, Leahy said that the government's challenge was "to defend our freedoms and not diminish them in this effort."

But constitutional freedoms are hardly the top concern of most Americans right now, so Leahy has recently found himself something of a lightning rod for criticism. On Oct. 2, Ashcroft condemned "the rather slow pace" he felt Senate Democrats were displaying in dealing with his anti-terrorism bill. "Talk won't prevent terrorism; tools can help prevent terrorism," Ashcroft said. In the closed-door confines of a Republican Senate lunch, he was even harsher. "He said he's had three weeks of meetings with Vermont Sen. Pat Leahy and the time for discussions is running out," a GOP source told Salon.

The bill soon passed, but tension between Ashcroft and Leahy -- personifying the current face-off between security and freedom -- did not. On Dec. 6, Ashcroft came before Leahy's committee to answer questions about the Bush Administration's counter-terrorism measures. The attorney general said: "To those who scare peace-loving people with phantoms of lost liberty, my message is this: Your tactics only aid terrorists, for they erode our national unity and diminish our resolve. They give ammunition to America's enemies and pause to America's friends."

Ashcroft clarified that he was referring not to critics like Leahy and others on the Judiciary Committee, but to those in the media who mischaracterize counter-terrorism proposals and laws. "The attorney general has the same right of free speech that we all do," Leahy said after the hearing.

On Wednesday, Dec. 19, Salon spoke with Leahy by phone to discuss our brave new world.

You took some heat during the debate over what ended up being named the "Uniting and Strengthening America By Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism," or USA PATRIOT Act. When that bill passed the Senate with your support, 98-1, you said that "I did my best to strike a reasonable balance between the need to address the threat of terrorism . . . and the need to protect our constitutional freedoms. Despite my misgivings, I acquiesced in some of the Administration's proposals to move the legislative process forward." What are your problems with the bill that passed?

First, the sense that we were defenseless without it. Underlying that was the feeling by some that our security was more important than our Constitution. I felt that enough was being said by everybody that neither was true. One, we were not defenseless without it -- we have stopped terrorists many times before. We just have to be better with the tools we have. And secondly, even assuming that there was any short term gain in turning back the Constitution, in the long term the damage is greater than anyone could find acceptable.

Like what?

When you start saying that we can forgo the rights to appeal, the rights of the press, that "We should suppress freedom of speech just this one time because it's important." It would take years or more to recover.

The American Civil Liberties Union has referred to some of the counter-terrorism measures as "Assaults on our freedoms." Is the ACLU right?

I think that there are a lot of people who would like to have legislation that would really assault our freedoms. That happens all the time -- it has to be up to those willing to put the brakes on to do so. Sometimes it's easy enough to get enough people so you can be successful and put the brakes on; sometimes it's not so easy. But the fact that there are more than just a very few of us asking questions about military tribunals indicates to me that at least [in that case] the brakes are going on.

The anti-terrorism legislation originally proposed by the administration -- and given strong lip service by others -- was stopped because we refused to be steam-rolled into the legislation, and we ended up with a package that had some very good things in it. It had some things in it that otherwise wouldn't have been there, too, but the overall package was light years ahead of what was originally proposed.

In June, you held an FBI oversight hearing, saying that "the image of the FBI in the minds of too many Americans is that this agency has become unmanageable, unaccountable and unreliable. Its much-vaunted independence has transformed for some into an image of insular arrogance." This came after a bunch of high-profile bungles -- the arrest of Russian spy Robert Hanssen, or the last-minute discovery of more than 4,000 documents that had been withheld from Timothy McVeigh and his attorneys. You were going to hold another hearing after Labor Day, but obviously Sept. 11 postponed that. Do you think that the problems within the FBI may have hindered its agents from preventing the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks?

That's one of the things we have to find out. One of the problems is that the Congress got in the habit of not having real oversight over the FBI. There was a feeling that, in a number of areas where the FBI had problems, that [former FBI director] Louis Freeh had corrected them. And indeed he had; after Ruby Ridge and some other problems he greatly improved a lot in the FBI. But there's also a reluctance, for whatever reason -- whether it goes back to the days of J. Edgar Hoover, I don't know -- to have responsible oversight.

But I said I would have no such reluctance. And when I became chairman, I said it would be one of the first priorities. It was an ideal time to do it; we had a new director coming in, and a new attorney general. And early on the attorney general and I talked, and we said let's look at this anew. Let's look at where there have been problems in the past and correct them in the future. One very obvious problem is that the FBI's computer systems and communication systems are antiquated. And that's been a problem in their ability to manage the flow of critical information. They've also had a lack of translators to handle the materials they were picking up.

I've felt this -- I've said it publicly for years -- that we need to have more of an emphasis on terrorism. I've felt that way as a member of the defense appropriations subcommittee. I've said it so many times I'm almost tired of hearing it: I'm not concerned about someone marching an enemy against us, or flying an air force against us, or sending a barrage of ICBMs against us because we're far, far too powerful. The reaction and retaliation of the United States would be massive. I'm far more concerned about terrorists, who are dedicated and have state-sponsored financing and training, driving into one of our major cities with a U-Haul truck containing weapons of mass destruction -- it could be chemical or nuclear or a dirty bomb, any number of things. The only way to stop something like that is before it happens. And the only way to do that is with good intelligence.

Are we doing enough now?

Well, I think we're doing more. But a lot of these things don't get put in place over night. To get a cadre of people who can translate languages other than fairly common languages. To put into place the connections -- sometimes which are diplomatic as much as anything else -- to get a heads-up. To realize that there are people -- and always will be people -- who want to damage the United States for whatever reason, whether because of our freedoms, our technology, our advanced wealth or power, whether it's done out of envy or ideology, if they're moved to attack us it's the same.

It sure doesn't feel like we've done enough.

In the past 10 years, with different FBI directors, different directors of the CIA, different attorneys general -- I'm talking about both Republican and Democrat -- we've had a number of successes. Most of which have not been publicized. I've been briefed about times when we've stopped an attack, and there hasn't been lot of press conferences about it for obvious reasons; we hope they won't do it again.

But we defend ourselves by defending ourselves -- not by taking away all our freedoms. I'm constantly encouraged by a quote attributed to Ben Franklin at a time when he literally faced the hangman's noose if he'd been unsuccessful. He said, "People who would trade their liberty for security deserve neither."

What's your take on the thousand or so individuals who have been detained by the FBI in the wake of the Sept. 11 attacks? Apparently 600 or so of them are still in police custody. Does that concern you?

It concerns me because I think it was done very, very quickly. It's been more reactive than proactive. It's too easy to say, "We're only holding people who are out of status on their visas." But there could be people [in custody] from a lot more countries than the ones who were targeted. It's a better thing to say, "Let's have a better way of tracking those with visas in the United States." But it seems that there are probably better checks and balances now. Though I'm not absolutely certain that there are as many as there should be. Look at the number of people whose lives have been disrupted. It seems to me that a better job could be made in determining why someone has been picked up and detained.

Last week, White House spokesman Ari Fleischer took you to task, on the president's behalf and probably behest, for not confirming enough of his judicial nominees. "There are more vacancies in the federal judiciary now than when President Bush came into office," Fleischer said. "The Senate has failed to act on 37 of the President's nominees to the bench. The failure to confirm qualified individuals in the judiciary hurts the American people." Fair criticism?

We're actually moving a lot faster than the Republicans did during the six years they were in charge, but I'm not using them as a touchstone in any way. Look, I've only been here since mid-July as the chairman of the full committee. It hasn't been quite six months, and we've had to get organized. We're moving very, very fast. We've gotten more judges through than either the first year of the first Bush's term or the first year of Clinton's first term, I forget which it is. And in between we've had a few distractions. There was Sept. 11, the anti-terrorism bill, staffs of 50 senators were forced out of their offices because of anthrax. Two anthrax letters were sent here to the Senate, including to my office. I think we've done pretty darn well.

On a personal level, how was it dealing with that anthrax letter sent to you -- was it frightening?

Well, I was more worried about the people in my office. Senators don't usually open their mail -- so much comes in there. We've got some awfully good people working in this office, and they often start off in the mailroom, as an entry-level job, and work up to a much better job. These are very talented, highly educated, highly motivated young people. So I was more concerned about them. Obviously, like all Americans, I was shocked about the people who did die because they did come in contact, either directly or indirectly, with the anthrax in the letter to Sen. [Tom] Daschle or the one intended for me. I come from Vermont where these things don't happen. We know each other, everybody's on a first-name basis, everybody's friends and neighbors.

How have you been getting along with your friend the attorney general? That was a bitter confirmation fight in January -- Ashcroft was confirmed 58-42, a close vote considering his status as a former senator. It can't be easy to work together after you opposed his nomination so vociferously.

When the confirmation hearing was over and the attorney general was confirmed I made a point to tell both him and the president, "He's now the attorney general, he got the votes necessary for confirmation, he was sworn in, and as far as I'm concerned he gets a clean slate and we start anew." We worked together on a lot of things as senators -- the E-Privacy Act, encryption technology. . .

Which is interesting, since Ashcroft as a senator leaned toward the privacy side of the privacy vs. national security debate. And as you said, you and he worked to allow American companies to export encryption technology abroad, despite the opposition of many in the law enforcement community, who argued that would hamper their investigations, including those of potential terrorists. Now, of course, the attorney general seems to have assumed a different side in that debate. Do you see this as indicative of hypocrisy or more just a sign of the changed times?

To be fair to John Ashcroft, he would say that he is now attorney general carrying out the directives of the president, which is different than the position he took as an elected senator, when he would carry out the position of his constituency. [Former Michigan Republican Senator, current Energy Secretary] Spence Abraham is also friend of mine. When he came in here he was supportive of completely doing away with the Department of Energy. Now he's the Secretary of Energy. I don't have any problem with that. In one position he was an elected senator, and the people of Michigan could make up their minds if they wanted to vote for or against him. It's another thing when you have the mandate to be Secretary of Energy and you're trying to make sure the department will run the best that it can.

And in fact since Ashcroft's been attorney general I've worked with him on the whole issue of FBI oversight. We used to talk several times a week about that and with the appointment of the new FBI director I told him I intended to begin a series of oversight hearings and he promised me nothing but complete cooperation and I received nothing but that.

But it got contentious recently.

I think we had a strained time during the terrorism legislation. I think he felt that if the administration said "Do it this way," the Congress would simply do it that way. But we wouldn't have done that when he was a member of Congress, we're not going to do it now, and we're not going to do it in the future no matter who the next president is. From his point of view he should be glad we improved it.

Why should he be glad?

Well, suppose we arrested someone under the law as it was originally proposed. They announce we've gotten a highly dangerous terrorist but then the courts have to void any arrest because it was based on a law that's unconstitutional.

As a former prosecutor I can tell you that arresting someone is easy. Making someone convicted, and making sure that conviction is sustained, that's the hard part.

I've heard you say that your job as a prosecutor was the best job you ever had.

No question. If you come into my office today -- my Senate office -- you'll see there's only one thing with my name on it, and that's a plaque up on my door from when I was state's attorney. The only photographs in my office are photographs which I've taken of family or of places in Vermont or around the world, which is no different than it was in my state's attorney office.

You told an interesting story to Jane Mayer of the New Yorker about a sting operation from those days, an investigation you conducted of Paul Lawrence, a state trooper with a high arrest rate, whom you caught setting up an innocent man, an undercover cop you'd brought in from Brooklyn. This influenced you in making sure that there are checks and balances when it comes to law enforcement. The story said this motivates you today in your battles with the Ashcroft Justice Department. Was that case really so powerful?

Well, I don't know what's the chicken and what's the egg on this. Whether my own thinking grew and evolved as a state attorney and that's why I was able to go after this person, or while I was going after this person I realized more fully that those of us with positions of trust and authority should respect that. In any event, I knew we had someone who had run pretty well free throughout the state -- except in my county -- arresting people, some of whom were probably guilty, but an awful lot of whom were framed.

When he came to my county, where I was the prosecutor, I saw an opportunity to expose him for who he was. So we arrested him, and put in motion what came out a year or so after I left the state's attorney's office when the governor made a very difficult decision and pardoned everybody [Lawrence] had arrested prior to my arresting him. He did that knowing that some of the people he had pardoned were of course guilty. But it was impossible to determine which ones were guilty and which ones had been framed. The governor had been put in an impossible situation.

But he also knew that had I not moved to arrest him -- and had we not had some police officers in that jurisdiction who felt as I did about positions of trust and authority -- he would have continued to operate as he had. And a whole lot of innocent lives would have been wrecked. So those police officers worked with me in my efforts to trap the person.

One of the things you learn very quickly as a prosecutor: it's very easy to charge someone, it's very easy to wreck someone's reputation just by bringing charges. Because no matter what they say about the presumption of innocence, usually the presumption is that the prosecutor has the right person and otherwise he wouldn't be in court.

That's why there's a greater burden on the prosecution to make sure that people's rights are protected. The defense attorney comes in after the arrest has been made, the courts come in after the arrest has been made, but it's the prosecutors who decide whether the arrest should be made at all. Or they decide that this person shouldn't be arrested and tried in the first place. The most discretion belongs to the prosecutor. He can do things police can't do, things a judge can't do, things a defense attorney can't do.

Do you really think the state's attorney job was better than the one you have now?

Well, I say that somewhat from a sense of irony. But it was a better job in this sense: I could make determinations for the public often on my own, and make sure that what I felt was right was the outcome. But when I was a prosecutor, I said that nobody should have that job for more than ten years or so. Because you do have the ability to play judge and jury. You don't have the checks and balances that you might have in a legislative body. Obviously I've been able to use talents -- to the extent that I have talents -- to a greater extent in the Senate than I could as a prosecutor. But it's also faster as a prosecutor.

Long before Sept. 11 you said, "Everybody is in favor of the First Amendment, but we'd have a hell of a time ratifying it today." You must feel that in today's climate it'd be doubly tough.

Not just in today's climate, in any climate. Take the worst-case scenario. Imagine we're in the McCarthy era. People would say, "What do you mean you want the First Amendment for Communists too?!" Today it would be, "What? For terrorists, too?!" It's easy to say "Free speech -- but not for that idiot that says 'fill-in-the-blank.'"

The beauty of the First Amendment -- it's an absolute. That's what so beautiful about it. You have the right to practice a religion -- or not to practice a religion -- as you see fit. It allows you to say what you want, including unpopular speech. It guarantees diversity. And when you guarantee diversity, you guarantee democracy.

Shares