In Preston Sturges' great 1944 World War II comedy, "Hail the Conquering Hero," Eddie Bracken plays a small-town boy mustered out of the Marines because of his chronic hay fever. He hides out in San Francisco, working in a shipyard and sending letters home to his mother with phony stories of his combat experience overseas. Dragged home by six Marines on leave, he finds himself acclaimed as the town hero, a survivor of Guadalcanal and an unwilling candidate for mayor.

In "The Majestic," which is set about 10 years later, Jim Carrey plays a blacklisted Hollywood screenwriter whose car careers off a bridge in a rainstorm. Surviving the accident but amnesiac, he washes up on the shores of a small California town still reeling from all the local sons lost in the war, and is mistaken for the town's war hero, who's been presumed dead and buried for the last decade.

Sturges' movie, like all his movies, is about the dementia that ordinary people are capable of, in this case the myths of American innocence and patriotism. "Hail the Conquering Hero" is both satiric and loving. Sturges' characters exist in a sort of patriotic fever dream, but it's their intense belief in that dream that winds up eliciting all sorts of small, vital acts of decency, and also allows Bracken's character to become a genuine hero. The irony of the movie is that the heroes that dream celebrates have seen too much to ever fully believe in the small-town life that honors them, even though they want nothing more than to believe in it.

Frank Darabont, who directed "The Majestic" (as well as "The Shawshank Redemption" and "The Green Mile"), is not a man given to irony. "The Majestic," which was written by Michael Sloane, is oppressively sentimental and uplifting. It's basically "Hail the Conquering Hero" redone as an unironic celebration of small-town American virtues -- that is to say, with no sense that the idealized vision it depicts is in any way false.

There's none of the pettiness or gossip that Sturges' characters are capable of, none of the crazy individuality that was his way of saying that ordinary people can be some of the most extraordinary characters you'll ever meet. Each of the characters in "The Majestic" fulfills his or her civic/central casting function: There's the kindly town doc, the good-looking dame who runs the diner, the doddering dear-old duffer with the town movie house, the cheerily boosterish mayor, the kids who've graduated high school and stayed on to marry their sweethearts, and the wise old black man, that contemporary movie sop to the sins of our racist past in real life as well as in our pop culture.

Even the embittered war vet turns out to be a stand-up guy. And true to the blasé familiarity of these types, the movie is populated with blasé actors (James Whitmore, acting with his eyebrows as usual) or actors striving to be blasé (David Ogden Stiers as the town doctor). All that's missing is Hal Holbrook, and damned if he doesn't turn up later on as a congressman.

When Peter admits that he finds it strange he can recall the plots of movies but not his former life, you wonder, Why, for God's sake? Towns like this exist only in the movies, and I kept waiting for some "Twilight Zone" plot twist telling us that Peter had somehow landed in one of his scripts. But no -- Darabont means us to take this hamlet utopia straight, not to snort when the town beauty reveals that she was inspired to become a lawyer after seeing Paul Muni in "The Life of Emile Zola." Henry Luce would have killed to get this perfect a vision of small-town America into the pages of "Life."

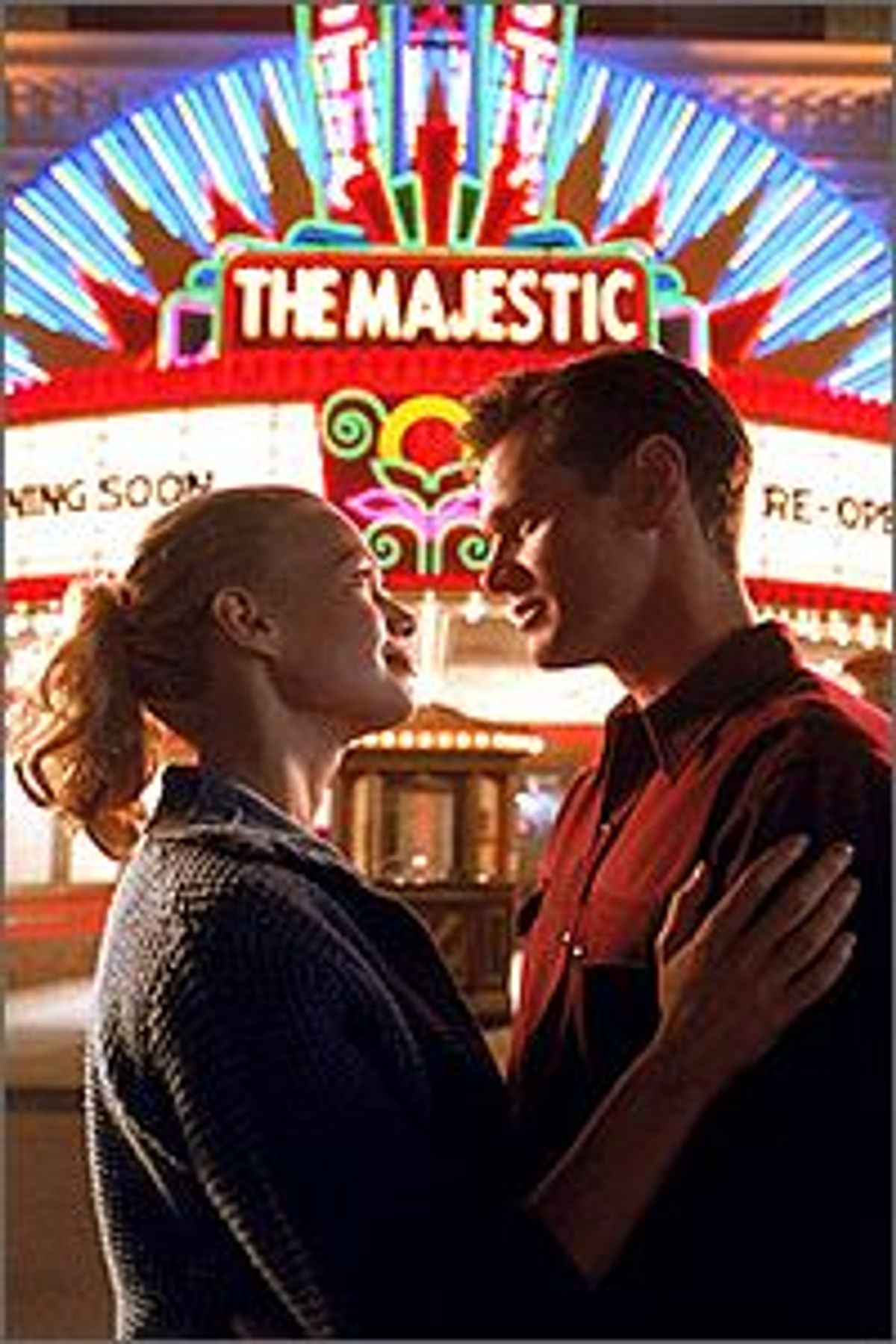

But Darabont works on a scale Luce could only dream of. Call it intimate elephantine. The movie, which goes on for two and a half hours, has been designed by Gregory Melton and shot by David Tattersall as a creamy pageant of iconic perfection. No stray litter blows around the streets, no greasy spoons mar the diner, there's not a tool out of place in the hardware store, the homes are all homey little nooks. Everything is spruced-up and inviting, as if company were always coming. The exception is the town's movie theater, the Majestic, which the owner, Harry (Martin Landau, playing a wasp but with so much baggy-cardiganed wisdom he might be auditioning for Doc in a road company of "West Side Story"), closed after the war because nobody wanted to go to the movies anymore. Carrey's Peter Appleton is the catalyst whose job is to fulfill the town's appetite for dreaming again.

He appears as a stranger who doesn't remember his own name but who looks strangely familiar to the townspeople who see him. When Harry spots Peter, he knows it's his son Luke come home miraculously from the war. Peter can't remember being Luke, but he gets caught up in the role nonetheless, courting Luke's girlfriend Adele (Laurie Holden, whose adorable nose is the only distinguishing thing in this small-town sweetheart role), and getting behind Harry's plan to spruce up and reopen the Majestic. Meanwhile, certain that Peter's disappearance after he's named as a former Communist means he's a big-time Commie spy on the lam, the FBI is hunting him down to make him testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee.

Peter's "communist" past is as flimsy and ludicrous as many of those dragged before the committee. He attended a few meetings of a socialist group in college because a girl he wanted to score with was caught up in the group. The blacklist is used shrewdly here, something the filmmakers can point to to say that theirs is not an unmitigated vision of American goodness. The trouble is that nothing about their version of the times rings true.

In the opening, Peter goes to see his movie "Sandpirates of the Sahara" at Graumann's Chinese, and we see a newsreel that reports, with undisguised contempt, the jailing of the Hollywood Ten, the group of writers and directors who refused to cooperate when called before HUAC. So how does Darabont reconcile that with the scene where another witness, refusing to cooperate, reads the committee members the First Amendment and receives a standing ovation from the crowd? People were too terrified to demonstrate in that way. (It took some heavy lobbying on the part of Edward R. Murrow, who had unimpeachable respect as a journalist as well as the power of CBS behind him, to go ahead with the documentary that spelled the end of Joe McCarthy.) Or the way the witness is let off on a technicality? (If HUAC was so willing to trample constitutional rights, why would they care any more about due process?)

So many writers and filmmakers have taken a superior attitude to the Americans gulled into believing the hysteria about a Red Menace rampant in Hollywood and the government and the military that I don't wish to add to it. But didn't it ever occur to Darabont and Sloane that the small-town people they are celebrating were likely just as susceptible to that propaganda? Yes, America did eventually see through HUAC and McCarthy, but it wasn't some spontaneous revelation that came from small-town ideas of fairness and decency.

Still, this confusion is exactly what might work in the picture's commercial favor. "The Majestic" is patriotic enough to be in tune with the times, but since the un-American evil being named is McCarthyism, liberals can stand up and cheer, too. I dread the thought that this cant might go over. "The Majestic" is one of those movies that makes you feel as if the national IQ was dropping while you're watching it. It's the return of all the homiletic clichés about an America that never existed, which were swept off the screen years ago, and which, when they were attempted during the "golden age" of the '30s and '40s, were never as popular as the wisecracking, fast-talking heroes and heroines of comedies and musicals and gangster pictures, all distinctly urban genres.

"The Majestic" moves toward a celebration of American isolationism, not just from the world, but within America itself. The only contact the residents have with the outside world seems to be newspapers and, fitting for a film so awash in illusion, movies. Outside of town lies heartache and phoniness and an evil government, and so Peter has to accept his role as the revivifier of town spirit. If "The Majestic" works for some moviegoers at all, it will be due to Jim Carrey. Nothing Jim Carrey does here is bad, exactly. He doesn't condescend to the conception, or make himself consciously heroic (except in the excruciating climactic scenes, and even then, he's not as inflated as the material would certainly allow him to be).

The movie trades on what's barely been noticed in his roles as crazies and spazzes and oddballs: his open-faced good looks. He's got an all-American freshness here that's more appealing than banal, and given the shameless melodramatic twists the movie indulges in, he underplays as much as possible. But he's still blanding himself out. By that I don't just mean that he's not showing sparks of his comic inventiveness (the role doesn't allow for it -- and he doesn't go saintly, as Robin Williams does in his dramatic roles), but that he's giving himself over to a conception that's not worthy of him.

There's no zip, no wit, not even the genuinely touching quality he had playing a man who was a bit of bumpkin in "The Mask," and certainly not the sweetness he showed as the hero of "The Truman Show," playing a man living in a hermetically sealed universe of small-town perfection. I feared for Carrey watching "The Majestic," in the way that watching the later upright men played by Gary Cooper made you long for the sexy young actor he was, the one Frank Capra crushed out of him. In the end of "The Truman Show," Truman left the stifling sterility of his make-believe world behind. The town in "The Majestic" is hermetically sealed as well, but by the residents' conviction, and eventually Peter's, that the outside world just isn't worth their while.

The best American movie heroes may have finally embraced virtue (like Bogart in "Casablanca"), but they kept their tough, faux-cynical veneer. In "The Majestic" goodness is equated with divesting yourself of all traces of cleverness or worldliness or doubt. It's exactly the vision of America that the blacklisters and Commie hunters were promoting, even though it could also be the sort of fantasy that blacklisted writers and directors like Dalton Trumbo, Ring Lardner Jr. and Edward Dmytryk might have had of finding themselves acclaimed as apple-pie American heroes. You just know that, if Peter ever goes back to screenwriting when the blacklist is over, he'll make lousy pictures.

Shares