Michael Mann is one of those filmmakers who makes sure that he's the star of his movies. Mann works in a huge, even overblown style, with the portentous winds of myth blowing. The style worked in his last movie "The Insider." The huge screen spaces that threatened to swallow up Russell Crowe and Al Pacino felt like the machinations of the corporate, media and political world their characters found themselves caught in.

It doesn't work in "Ali," which constantly struggles to attain the level of myth. Didn't Mann realize that Muhammad Ali already is a myth? Had he just told Ali's story, and not let his own excess get in the way, the movie might have succeeded. As it is, his style constantly gets in the way, pumping up events that are so embedded in our consciousness they don't need to be made any bigger.

The screenplay, by Stephen J. Rivele and Christopher Wilkinson, and Mann and Eric Roth, spans 10 years, from when Ali won the heavyweight title from Sonny Liston in 1964 to when he reclaimed it from George Foreman in Kinshasa, Zaire, in 1974 -- the famous "Rumble in the Jungle." That's a good arc, bookended as it is by two triumphs, and encompassing the four years when he was banned from boxing for refusing induction into the Army, a decision later unanimously overturned by the Supreme Court when it ruled that Ali's right to practice his religion had been violated.

At first it looks like Mann's style might be just the way to go. The montage that opens the movie contrasts the public showboating of Ali (then Cassius Clay, played by Will Smith), boasting that he would defeat Sonny Liston, with the intensity of his training when there was no audience around. And all of this is intercut with a deliciously sexy scene of Ali's idol, Sam Cooke (David Elliott, doing a pretty damn good impersonation), performing in a Miami club.

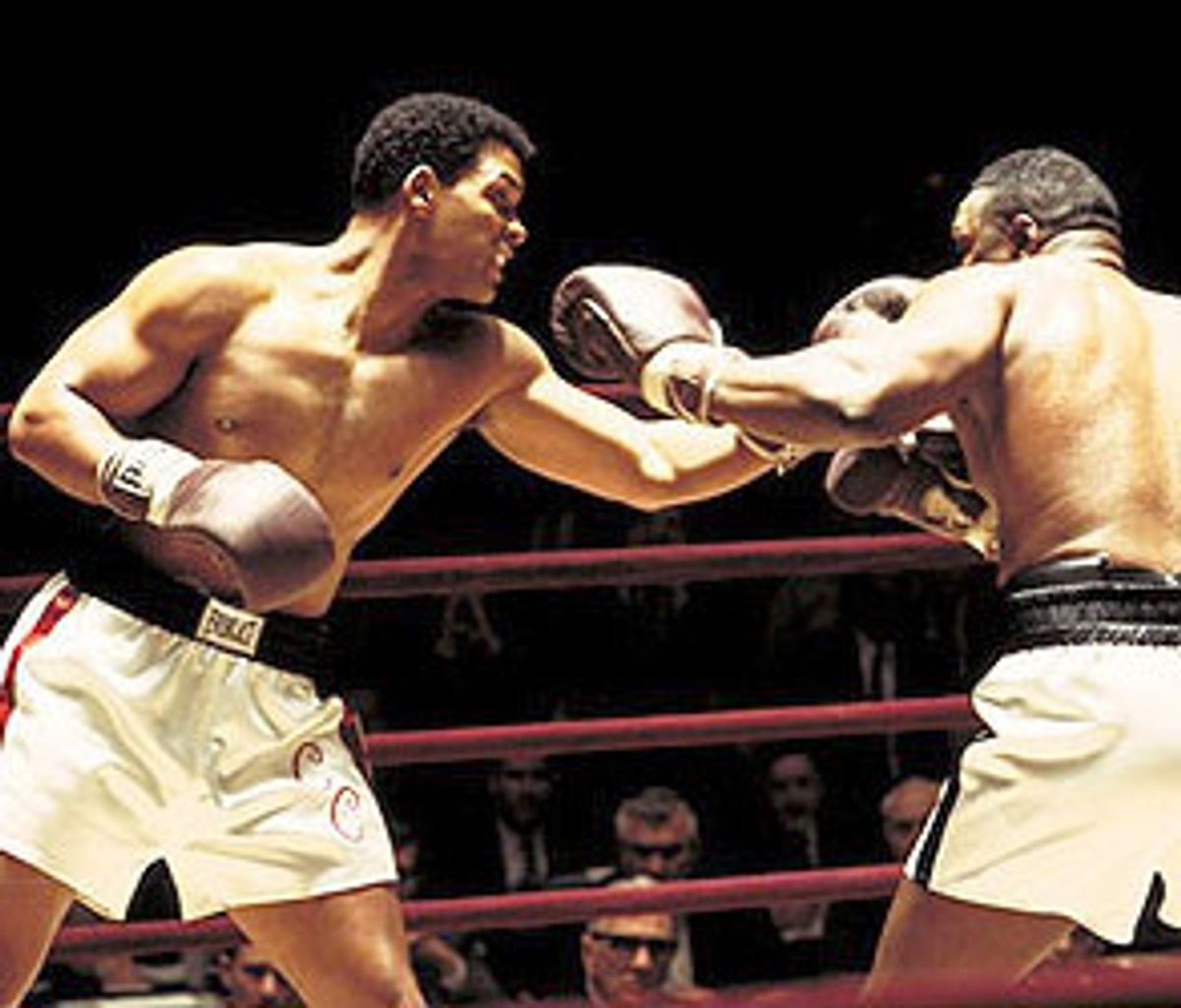

The fight sequences that begin and end the film are both smartly conceived and executed. In the first, we watch from Ali's point of view as Liston (Michael Bentt, one of a series of real boxers who play Ali's most famous opponents) lumbers menacingly towards him and throws a punch that whooshes by the camera. That's, of course, what happened in the legendary fight: The 23-year-old Clay stymied Liston with his speed. As the film's Ali grows more confident, Smith captures his arrogance, circling the ring as he contemptuously takes in the damage he's done to Liston, his agility conveying to the huffing and puffing (and furious) champ that the power of his punch counts for nothing.

That's the same message Ali sends to George Foreman in the climactic fight scene in Zaire, the bout in which Ali took back the title from Foreman (who had taken it from Joe Frazier). In "On Boxing," Joyce Carol Oates wrote that when Ali returned from his forced hiatus the speed of his youth was gone, but he had learned a terrible lesson: He could take a punch. Foreman was such a powerful fighter, and Ali had suffered so badly at the hands of Joe Frazier, that even his own camp was sure he was going to be terribly hurt in the fight.

Even if you know what's coming at this point in "Ali" (a victory described blow-by-blow a few years back in the documentary "When We Were Kings"), it happens so fast that you're not prepared for it. The cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki shoots the fight scenes close in, so we feel each opponent's breath, but there are times when you want more of a wide view to allow you to see their footwork. And the washed-out grain used to reflect what Mann thinks is a semi-documentary style has none of the rich sensuousness of Lubezki's work for "Great Expectations" director Alfonso Cuaron. At the same time, the style does work to put you in the midst of the action, and to make what's going on outside the ring fall away.

Elsewhere in "Ali" you may feel in the midst of the action without bearings. If you don't know a lot about Ali, or if you don't know the names of the people who surrounded him -- his trainer Angelo Dundee (Ron Silver), his friend and "voodoo" man Bundini Brown (Jamie Foxx, who keeps bringing the movie needed jolts of energy), his photographer Howard Bingham (Jeffrey Wright, who stands around looking suspicious, as if waiting for a role to play) -- you're very likely to feel lost.

I like movies that cut away the fat (even though Mann's method stretches the movie out to two hours and 40 minutes), that allow you to work out the relationships on your own without a lot of phony exposition. But names and introductions are muffled here. When Ali, in Kinshaha, asks someone what the chant "Ali! Bumaye!" means, the answer ("Ali! Kill him!") is lost in the surrounding noise. Mann can ladle the syrupy spiritual score by Lisa Gerrard and Peter Bourke on the soundtrack to make us feel, in scene after scene, as if we're in church. Or he can pull the camera back to give us big expanses of space in which dust motes float in the light, or bring a camera in so close that we might be having an anatomy lesson. But he can't keep the camera still to allow two people to have a conversation or to find a way to provide basic information for the audience.

The movie isn't a disaster. The script very clearly says that Ali was a means of publicity and a cash cow for the Nation of Islam (Ali was managed by Elijah Muhammad's son Herbert for years). And the movie is not at all complimentary toward the Nation. It shows how Ali's childish adherence to the Nation's sexist rules on what constituted proper dress and behavior for women broke up his first marriage (to Sonji Roi, played with insouciance by Smith's real-life wife Jada Pinkett Smith). And we see him, parroting the ruling of "the honorable Elijah Muhammad," snubbing Malcolm X after Malcolm has been suspended from the Nation.

But Mann can't decide whether he wants to treat the story in the urgent style of a late-breaking news item (most of the atrocities of the '60s are present in re-creation or newsreel footage) or as a monument worthy of Mount Rushmore. When Ali refuses the Army induction, you want the camera to stay on Will Smith's face, and instead Mann pulls back so we can see the ornate hall he's standing in. Mann is always heightening, heightening, heightening, but the drama feels somehow both leaden and cut loose from any moorings that would ground it.

For someone like me who loves Muhammad Ali, "Ali" is a major disappointment. This could be the only movie we'll get on the fighter, and it's just not good enough. But for people who feel as I do about Ali, the surprise here is Will Smith. Frankly, I didn't think anyone could pull off the role. Who could live up to that charisma, that motormouth wit? Who could possibly capture the beauty of the young Cassius Clay? Often, actors playing real people uneasily straddle the line between impersonation and inhabitation. Smith crosses it as much as the script and direction allow. Here, 30 pounds heavier, he's in fighting trim, muscled and sleek and, in the opening scenes, bouncing across the ring. One of the most stunning moments in Smith's performance is near the end, when Ali, after defeating Foreman, slumps to the floor of the ring, a marked contrast to his ebullience following his defeat of Liston. You look at Smith's face and know there's no innocence left in Ali anymore, that every victory from now on will cost in a way the victories of his youth didn't.

The key to the whole performance is in Will Smith's face, usually so friendly, conveying nothing more than a desire to be liked and an unwillingness to do anything that would prevent an audience from responding to him. As Ali, his eyes are heavy-lidded, as if there's some part of him that will always be private, ready to cut off anyone at any moment. Smith is right at home playing Ali the cutup (and his mimicry of Ali's speech patterns is often uncanny), tossing off jokes and his wonderful doggerel poems to reporters and fans, sparring with his great admirer, champion and most stubborn interviewer Howard Cosell (played by a vastly amusing Jon Voight, done up in prosthetic makeup; Voight and Smith effortlessly get the prickly affection between these two men). But he's also at home with the side of Ali that wasn't ingratiating, that was determined to do things his way, whose outspokenness caused uproars ("Man, I ain't got no quarrel with those Viet Cong. Ain't none of them ever called me nigger!"), who wasn't deterred when he was despised by the white public read (for those who have only known Ali as a beloved public figure, it wasn't always so).

What Smith is reaching for is Ali's transformation from a kid into an adult, and his realization that, though he always made good on his boasts (which, of course, means they weren't boasts), the stakes got higher when he went from making a boast to taking a stand. He confers gravity on Ali without deifying him or cutting the life out of him. Smith reminds us of how Ali went from delighting us to moving us. Michael Mann is so busy whipping up the atmosphere and erecting his Parnassus that he has little time to work with Smith. The actor at times seems to be carrying the movie on his expressions -- sly or foreboding or defiant -- alone. He made a believer of me. He's taken a leap as an actor and landed on his feet. Why, oh why, couldn't he have touched ground in a movie worthy of his hard work?

Shares