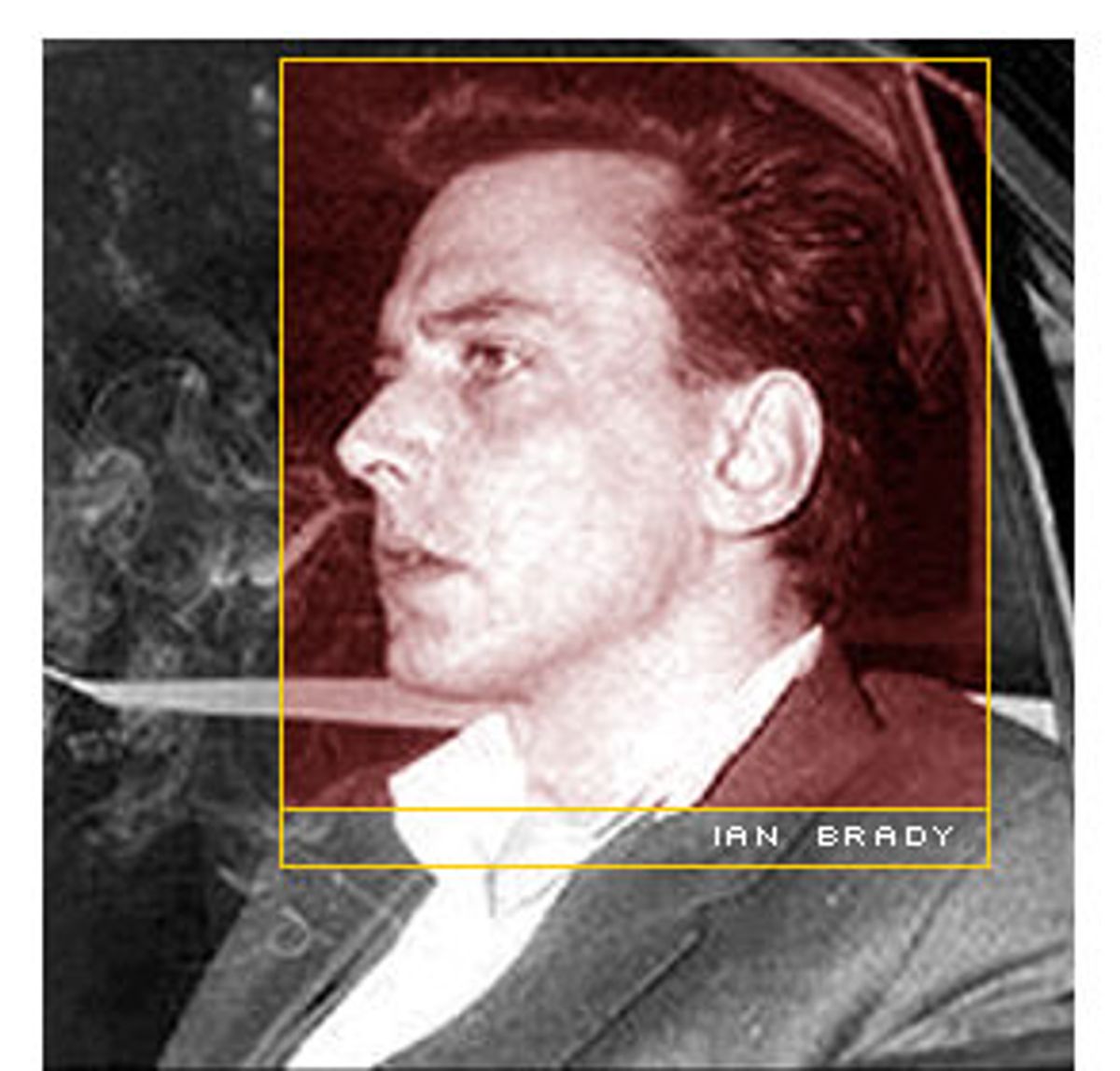

Ian Brady's darkly handsome visage is forever floating to the surface of Great Britain's collective psyche, a sleek, brooding specter of malevolence and sadism that the tabloids and the broadsheets simply cannot leave alone. The most iconic image in Brady's portfolio of infamy was snapped in 1966 as he was being tried for three of his five murders of Manchester children and teens during a two-year killing spree. Sitting in the back of a police car on his way to court, the stylish, Scottish-born sociopath exudes an imperious nihilism as foreboding as it is seductive.

In one particularly sinister, oft-used head shot, a defiant Brady looks like he could give suspected terrorist mastermind Mohammad Atta lessons in ghoulishness. On February 29, 2000, the Sun took up the whole front page with this picture and the bold legend "Brady: Let Me Leave This Cesspit in a Coffin." The story told of the murderer's campaign to starve himself at Ashworth Mental Hospital, near Liverpool, where he's a permanent resident. So far British justice has been unwilling to intervene, and his keepers have been force-feeding him.

The most chilling photo is from 1987. In it an older Brady, in sunglasses and surrounded by policemen, returns to the Saddleworth Moor, near Manchester, to help find the grave of his very first victim, the lovely, 16-year-old Pauline Reade, whom Brady had consigned to the earth some 20 years before. When they uncovered the corpse, it was apparent that her throat had been cut and that she had been sexually assaulted. To this day, the body of one other victim, 12-year-old Keith Bennett, has never been located on the moors where Brady says he buried him.

Given the recurring simulacra of horror, it's understandable that all hell broke loose in Albion once American publisher Adam Parfrey of Feral House revealed that he would be releasing a manuscript the child killer had produced under the tutelage of acclaimed crime and occult writer Colin Wilson. Titled "The Gates of Janus: Serial Killing and Its Analysis," the book is a mixture of sociology, psychology and philosophy wherein Brady theorizes that serial murderers rise above the "bovine conformism" of the human herd. He then goes on to dissect the work of his peers: Ted Bundy, John Wayne Gacy and Peter Sutcliffe (aka the "Yorkshire Ripper"), among others.

Here in the States, where few but the most ardent crime buffs know about the homicides Brady and his paramour Myra Hindley perpetrated in the early '60s, the book has been selling online since September. The book's journey to the shores of Brady's homeland has been far more tortuous. Ashworth Mental Hospital initially objected on the grounds that their privacy rules had been violated, but they eventually relented. Relatives of the victims called the book obscene on principle, and pundits raised Cain because Parfrey paid a $5000 advance.

"Ian Brady doesn't see a cent," asserted the L.A.-based Parfrey when asked about the deal. "The proceeds go to Benedict Birnberg, Brady's solicitor, who has reconfirmed to me that the money goes to Ian's 90-year-old mother. [Brady] has no way to spend the money; no commissary accounts, nothing. After all, he is trying to kill himself."

A British court cleared the way for the book to be released in Britain, where it became available in stores on Dec. 4, but that only provided more fodder for Fleet Street's insatiable minions. British journalists leap at any opportunity to write more about their caged pet demon, now 64 and decrepit. In the '60s, when both Brady and accomplice Hindley escaped the hangman's noose by a few months because of the abolition of the death penalty in Britain, reporters clamored for blood. More recently, when Brady's appeal for the right to stop eating failed, one cheeky tabloid started a "Post a Pie to Brady" effort to "keep the evil bastard alive." Even the far more sophisticated Guardian ran a commentary by columnist Hugo Young on March 2, 2000, in which the author demanded that both Brady and Hindley rot in their cells.

"The Moors Murderers have no parallel in the culture, no equal in the almanac of foul, remembered crimes," wrote Young. "A vast publication industry has been built on their continued existence unhanged, after butchery which 10 years earlier would have sent them to the gallows."

This national obsession strikes me as a sort of fetish, like the mania for Nazism that an endless march of films, books and documentaries will never slake. But why Brady and not some other notorious psychopath? Certainly there have been more successful killers in Britain and in the States, murderers far more monstrous in their modus operandi. For example, Charles Manson, though iconic, doesn't get nearly the amount of spilled ink in America that Brady gets in England.

Part of this intense hatred has to do with the nature of the crime itself and the climate in which it took place. The early '60s was a more innocent time, in some ways, or at least better about keeping its hypocrisies hidden. Both Brady and Hindley were young and good looking, and on the surface they seemed like any other working-class couple of the era. With Brady, then 27, dressed in collar and jacket, and Hindley, then 23, in her bleached-blond bouffant and go-go attire, the two of them together could have been up to nothing more fiendish than a hot time at the local disco.

They met while working for a small chemical corporation near Manchester. Brady was a stock clerk with a criminal past, having done some time for petty thievery. He planned to execute future criminal enterprises, and maintained connections to Britain's underworld. More significantly, Brady was an intellectual with unusual predilections. Hitler, Dostoevski and De Sade were a few of his favorite authors; "Crime and Punishment" and "The Possessed" were his favorite books. Already he had declared himself an enemy of society, and he was but one step away from the Dostoevskian hypothesis that if God is dead, all things are permitted.

Myra Hindley, however, was nothing close to an intellectual. By all accounts, she was a completely average young Catholic girl with an affection for animals and children, perhaps a bit more naive and easily led than most. Not long after she went to work at the same firm as Brady, she fell in love with him. He spurned her for some time before coming around, but once he did, Hindley became slavishly devoted. Brady introduced her to S/M and amateur pornography, and filled her credulous noggin with his peculiar blend of moral relativism and the Marquis de Sade. She became his willing apprentice, his faithful servant. When his talk of criminal enterprises turned to talk of murder for pleasure, she procured his young victims for him, offering them rides or otherwise luring them in for the kill.

Together Brady and Hindley used the young boys and girls they abducted for sexual gratification, on occasion forcing them to pose for pornographic shots before raping and killing them. They buried the bodies on the moors, and sometimes even enjoyed picnics and tea parties on the graves. The snapshots they took of themselves in these gay vignettes later led investigators to the graves of 10-year-old Leslie Ann Downey and 12-year-old John Kilbride.

What gave the pair away was their attempt to recruit Hindley's brother-in-law David Smith. Smith walked in on Brady as he was finishing off 17-year-old Edward Evans with an ax in the council house Brady and Hindley shared with her grandmother. But instead of joining their homicidal cabal, Smith went to the cops, and that was the end of the duo's bloodstained adventures. On May 6, 1966, they both received life in prison for their crimes.

For many years, Hindley insisted that Brady alone killed their victims and that she was an unwilling accomplice. She later changed her tune and expressed sorrow for her deeds, all in the hopes of winning parole. But whenever the parole idea has been floated in the press, it's immediately been shot down. Brady for his part has demonstrated very little remorse and a longing to die unless his situation in the mental hospital improves. At one time hospital administrators allowed him access to a word processor and let him transcribe books into Braille for the blind, but no longer.

In his introduction to the book, Colin Wilson quotes from one of Brady's letter to him, part of an ongoing, 10-year correspondence between the two:

My life is over, so I can afford honesty of expression those with a future cannot. If I had my time over again, I'd get a government job and live off the state ... a pillar of society. As it is, I'm eager to die. I chose the wrong path and am finished.

Brady comes off as far more bellicose in "The Gates of Janus." Janus is the two-faced Roman god of doorways and beginnings, the entity from which January derives its name. The choice of this title implies several layers of meaning: Brady looking backward at his own actions; Brady as a duplicitous man with two sides to his personality; and so on. Janus' temple in the Roman Forum was a double-gated structure with high symbolic value to the Roman state. When the gates of Janus were closed, the Roman Empire was at peace. When they were open, it indicated that Rome was at war. In Brady's book, at least, those metaphorical gates are open, and it is with civilization that he does battle. Hence Brady's quote from Shakespeare's "King Richard III" at the beginning of the first chapter: "Let us to it pell-mell; if not to Heaven, then hand in hand to Hell."

Like a modern-day incarnation of Milton's Satan, Brady delivers a discourse that is twisted, self-serving and strangely persuasive. Quoting liberally from the likes of Dylan Thomas, Byron, Nietzsche, Sun Tzu and Buddha, Brady mocks what he regards as the rank mendacity of the status quo. Society's laws and morality derive from the ruling classes and their need to maintain their collective position at the pinnacle of the food chain, according to Brady. In his eyes, these assorted generals, politicians, lawyers and so on are just as rapacious and cruel as any serial killer. He asks:

How many centuries would you suppose it would take for freelance "criminals" and "madmen" to equal the numerical carnage the "law-abiding" and "sane" can achieve in such a comparatively short span of time? One should cultivate discrimination in accepting or respecting one's moral "superiors." So often they certainly are not.

Brady may be technically correct here, but with a few more Osama bin Ladens in the world, freelance psychopaths might one day even the score. This skewering of modern mores takes up the first half of the book, with the second half given over to a far more intriguing section wherein Brady examines the crimes of his fellow serial killers. Like a literary critic analyzing his favorite novels, Brady takes on the mantle of a murderous eminence grise -- a professorial Hannibal Lecter holding forth on the practitioners of his métier.

Speaking of Richard Ramirez, known as the "Night Stalker," Brady in fact compares serial killers to writers, as they both pursue "the quest for immortality" with serial killers using "a knife rather than a pen, skin rather than paper." He further states that "anything less a medium than human material" is no substitute for the "actual experience of writing on living and breathing pages." Considering Ramirez's delight in raping and humiliating his victims before consigning them to oblivion, this commentary is especially chilling.

Brady is quite clear that he regards a certain class of serial killers to be superior beings, gods by their own choice. For him, John Wayne Gacy was "the perfect psychopath." And Ted Bundy takes on the mantle of some bloody demiurge:

Life was too short to be restricted and deformed by the selfish designs of the already privileged. [Bundy] would thoroughly enjoy giving them a lesson in idiosyncratic "justice," and lead them on a dance worthy of Zarathustra, "lover of leaps and tangents," monster of divine laughter! A Dionysiac demon was rising from the abyss of his subconscious, eager to take flight, sink talons and teeth into living flesh, savor the blood, rip out the soul.

Brady wanted his book to be published under the pseudonym "Francois Villon," the renowned 15th century criminal/poet of France, but his publisher persuaded him to use his own name. Brady barely touches on his own crimes, and Feral House's Parfrey says Brady's solicitor has an autobiography under lock and key. One wonders if Brady is toying with us from his living grave at Ashworth, trying to whet the public's appetite for his life story, to be published on his death.

Certainly, Brady commands an audience. Something about the mournful poetry of the moors and the folie à deux between Brady and Hindley has snared the imaginations of many in Britain and out. Manchester-bred rock star Morrissey wrote a controversial Smiths song, "Suffer the Little Children," wherein Brady's victims call out from the grave, "Oh, find me ... find me, nothing more/We are on a sullen misty moor."

American novelist Peter Sotos makes incessant references to the case in his work, and on the cover of his book "Tick," there's a picture of Pat Hodges, a little girl Brady and Hindley enlisted to read newspaper accounts of the children they had "disappeared" into a tape recorder. Painter Marcus Harvey incurred the wrath of visitors to the much-maligned 1997 "Sensation" show in London with a portrait of Hindley that viewers pelted with eggs.

Brady's writings, as macabre and vengeful as they are, cannot be easily dismissed, even for those who find them repulsive and repugnant. They offer a unique moral lesson, a glimpse into the abyss of a damned soul as well as an illustration of the reductio ad absurdum of the moral relativism Brady espouses. In the end, that moral relativism is the slipperiest of ethical slopes, leading those who embrace it without hesitation to the sort of self-made hell in which Brady evidently now dwells.

Shares