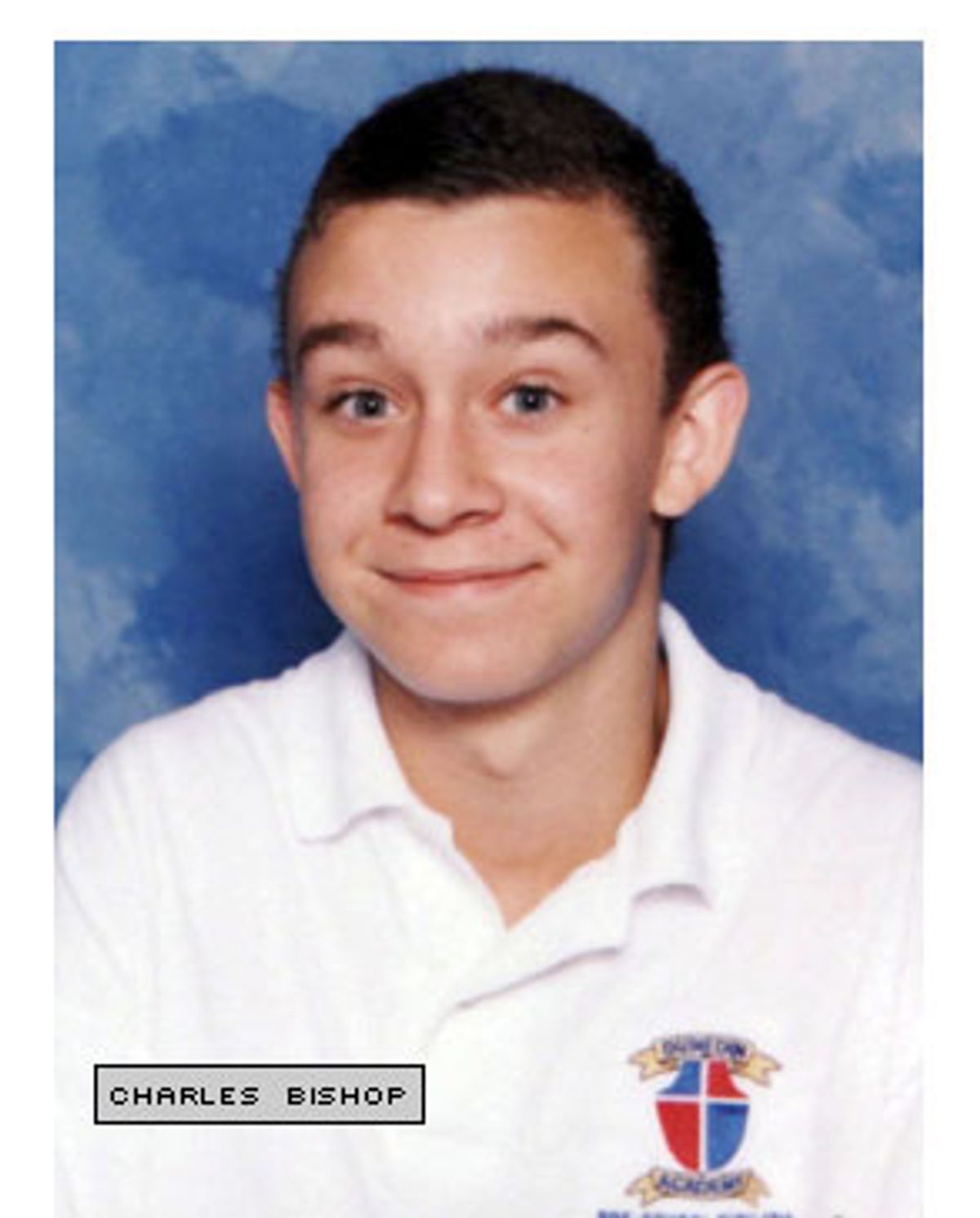

We now know a little bit more about Charles Bishop, the 15-year-old Florida high school student who flew a small plane into a Tampa office building on Saturday and killed himself -- carrying a suicide note in his pocket expressing solidarity with Osama bin Laden and the terrorist attacks on New York.

According to the Associated Press, Bishop earned straight A's, carried the flag at school assemblies, planned bake sales for his school, entered essay contests run by the Daughters of the American Revolution and wanted to join the Air Force. His suicide and the pro-terrorist note he wrote have perplexed those he left behind, who knew him as an apparently patriotic young man.

When I read these details I shook my head, as no doubt most readers did. I also wondered how the story would play across the radar screens of the conservative pundits who recently turned the life story of John Walker -- the American-born, Marin-raised Taliban fighter now in custody on a U.S. warship -- into a broad indictment of American liberalism.

Walker's background -- raised in permissive Marin County, hotbed of "cultural relativism" -- fueled his traitorous behavior, according to Shelby Steele in the Wall Street Journal. Andrew Sullivan also blamed Marin liberalism, writing in the Sunday Times of London that "Walker's own sad young life is an obvious testimony to how lost some young souls can get in a culture where nothing is deemed sacred, nothing right, nothing wrong, and everything equally true."

Given that argument, one can only wonder what to make of Bishop's story. Is Tampa -- in many ways the cultural antithesis of Walker's Marin -- also responsible for fueling bin Ladenism? Does belting out "My Country 'Tis of Thee" at school assemblies, as a teacher recalls Bishop doing, indicate latent terrorist tendencies? Does a desire to join the Air Force suggest a future in treason?

Of course not. Bishop's story can no more be reduced to culturally deterministic oversimplifications than Walker's could. In both cases, we're dealing, it seems, not with mature ideologues possessing consistent worldviews but rather with troubled adolescents taking figurative potshots at the adults around them. (Walker, now 20, was not much older than Bishop when he first turned to Islam.)

But Walker fit the social right's culture-wars template so conveniently that writers like Steele and Sullivan couldn't resist his poster-boy-ization. Now that we have the counterexample of Bishop, they are unable to respond coherently.

Thus, on his weblog Tuesday, Sullivan scratches his head: "This story of an isolated, desperate early adolescence is heart-wrenching stuff. Yes, I know he seemed to have sympathy for bin Laden. But he was 15 years old. Can we also have sympathy for him?" This plaintive query stands in stark contrast to Sullivan's tough-guy rhetoric in the days following Walker's imprisonment, when he knocked both "Bay Area dupes" and President Bush for suggesting the possibility of compassion toward Walker.

Certainly, Walker is older than Bishop; our legal system draws a distinction between minors and adults, and Walker, having now crossed that magic line, should properly stand trial for whatever charges our government chooses to bring against him. If Bishop had survived his sorry stunt, his age might have protected him from the full weight of the law (although given that Florida is the state that sentenced 14-year-old Lionel Tate to life in prison after he killed a playmate, a surviving Bishop might have faced as much trouble as Walker).

But let's not whitewash the violence of Bishop's act: Stealing an airplane and flying it into an office building is potentially catastrophic mayhem that could easily have killed lots of people. Where Walker bore arms in a war against other soldiers (we don't even know whether he actually ever fired a shot), Bishop targeted civilians in the American "homeland." That we're able to view his death as a sad suicide rather than a terrorist crime is a matter of sheer luck.

In any case, the law, loving precision, declares a world of difference between a human being one day before his 18th birthday and the same person one day after. But that difference may not register on the scale of emotional maturity, which can fluctuate wildly from teenager to teenager and even from year to year within the trajectory of a single teenager's life.

If we're talking about sympathy and compassion, you can surely -- without suspending the legal process -- extend it as equally to a mixed-up 20-year-old as to a screwed-up 15-year-old. Unless, that is, you want to use them as rhetorical fodder on behalf of an intolerant cultural agenda. Then, you have to twist yourself into knots until you come up with a rationale for embracing one while scorning the other. Watch those knots tighten on the talk shows and Web postings over the next few days.

Shares