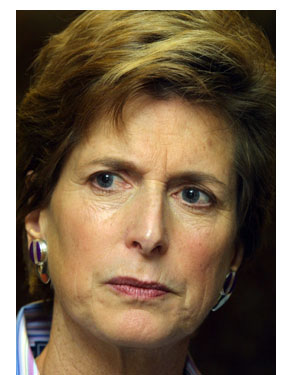

The ombudsman for the Environmental Protection Agency says he was punished by administrator Christine Todd Whitman after he opposed an agreement to sharply limit the amount of money financial titan Citigroup — a principal investor in Whitman’s husband’s venture capital firm — would have to pay in a controversial Superfund cleanup case.

EPA ombudsman Robert J. Martin, who functions as the agency’s public interest advocate, alleges that Whitman ordered his office reassigned within the EPA bureaucracy and stripped of its independence after he opposed a nuclear-waste cleanup settlement with Citigroup that would limit its liability to a fraction of the cleanup cost.

Martin made the conflict of interest charge against Whitman in a lawsuit filed Jan. 10 in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia. The suit sought a temporary restraining order to prevent the ombudsman’s duties and investigative files from being transferred to the EPA’s Office of Inspector General, an agency Martin has clashed with in the past and is currently investigating. Through a spokesperson, Whitman denied Martin’s charges.

Martin won a crucial legal battle Friday, when Judge Richard W. Roberts ruled in his favor, delaying his reassignment until Feb. 26. “Before the hearing I said that I was cautiously optimistic,” Martin said. “I now rejoice that truth has prevailed and justice has been done.”

Martin is opposing, among other EPA moves, a pending agreement that will limit Citigroup’s liability to $7.2 million for cleaning up a nuclear waste Superfund site in Denver. Officials in EPA’s Region 8, which includes Colorado, reckon the cost of cleaning up the Citigroup-owned Shattuck site will be $22 million to $35 million.

Martin’s own analysis separately concluded that a proper cleanup of the site, which is located in a working-class neighborhood and contains a 15-foot tall mound of radioactively contaminated soil, would cost as much as $100 million. Limiting Citigroup’s liability to $7.2 million would therefore transfer as much as $93 million of the cleanup’s cost to taxpayers, Martin alleges.

Whitman’s actions, the ombudsman charged in his lawsuit, will “have the immediate effect of muzzling the voice of accountability within the EPA that has been, and would otherwise continue to be, the primary source of information about the inadequacy of clean-up plans of highly toxic waste sites affecting the public and the environment.”

Historically, the ombudsman has not wielded decision-making authority at EPA, but has responsibility for investigating complaints about the agency brought by citizens, local governments and corporations. The role has caused friction between the ombudsman and the rest of the EPA before, but this is the sharpest conflict to date.

Whatever the reason for Whitman’s move — and Martin has not produced evidence that she intervened to benefit Citigroup — the reassignment could well de-fang an office that has been a sharp critic of industry and an advocate for tougher environmental protection. Coming at the same time as the widening Enron scandal, the lawsuit is one more headache for the Bush administration, which stands accused of being more concerned about its corporate patrons than the public interest. Whitman’s move against Martin has been harshly criticized on Capitol Hill — with the strongest opposition coming from Western-state Republicans.

Sen. Wayne Allard, R-Colo., wrote to Whitman Jan. 8 asking that she delay the transfer until Congress can analyze it. “She’s decided to put him in the Inspector General’s Office, and the way I understand the way it’s set up … he does not maintain his independence,” he says. Allard praises ombudsman Martin and his chief investigator, Hugh Kaufman, for reversing what he calls EPA’s mistaken approach to the original cleanup of Denver’s Shattuck site, and for being the first representatives from the EPA who listened to his constituents’ concerns about radioactive waste. Kaufman is also a plaintiff in the lawsuit against Whitman.

Allard declined to express an opinion on the validity of the financial conflict-of-interest allegations against Whitman. “The charges of conflict of interest by the ombudsman, I think, need to be reviewed,” said Allard, who added, “If the courts determine that there is an improper settlement [in the Shattuck cleanup] because of conflict of interest, I think that they will deal with that.”

Judge Roberts’ Friday ruling means that Martin will remain ombudsman at least long enough for him to challenge the Shattuck cleanup settlement in court and for Congress to hold hearings on Whitman’s attempt to reassign him.

Martin and Kaufman are not newcomers to controversy. In the early 1980s, it was Kaufman’s whistleblowing that led to the resignations of President Ronald Reagan’s EPA administrator, Anne Gorsuch, and Superfund program administrator, Rita Lavelle, over a scandal involving diversion of EPA money to Republican Party political activities. Kaufman was then the chief investigator of EPA’s Hazardous Waste Management Division.

Kaufman argues that his current dispute with Christine Todd Whitman involves even more serious public interest concerns. “If Whitman doesn’t back down on this, we may as well kiss representative government as we’ve known it goodbye. Because it means that a top government official can rule in cases that directly benefit her financially, get called on it, tell her accusers to get lost, and get away with it.”

No one has proven that Whitman made her decision with the specific intention of benefiting Citigroup. But the company is the first one listed on the public financial disclosure report that Whitman filed upon being confirmed as President Bush’s EPA administrator. She and husband John Whitman are listed as owning between $100,000 and $250,000 worth of Citigroup stock, but the couple’s ties to Citigroup go much deeper. John Whitman worked directly for Citigroup from 1972 to 1987 and reportedly received a year-end bonus from the company as recently as 2000. Today, he is a managing partner in Sycamore Ventures, a $550 million venture capital firm whose Web site explains that it was “spun out of Citicorp Ventures, Ltd. [in 1995]. Today we continue to enjoy the backing of the worldwide network of Citigroup, which remains one of our largest investors.”

Whitman declined, through agency spokesman Joseph Martyak, to be interviewed for this story. Deriding the ombudsman’s charges as “specious allegations,” Martyak says that “the administrator, of course, is concerned that these kind of accusations are being raised because they’re totally unfounded … The conflict of interest that’s being proposed here simply doesn’t exist, because she’s been up front about what her involvement is with Citigroup.” He claims that the terms of agreement between the EPA and Citigroup were first reached in December 2000, under the Clinton administration, and before Whitman even took office. The administrator’s reassignment of the ombudsman, Martyak emphasizes, is a “totally separate decision” from the Shattuck case, and one that he says will give the office greater independence.

John Whitman was unavailable for comment, but another managing partner in Sycamore Ventures, Peter Gerry, called the conflict of interest accusations “far-fetched, convoluted, self-serving and contrived.” Gerry, who said Whitman and the other founding partners of Sycamore Ventures had trained and worked together at Citigroup, added, “I’m not going to deny that [Citigroup] is a big investor of ours. We treasure our relationship there. But we have lots of other big investors, too.”

Gerry declined to specify how much of Sycamore’s investment capital came from Citicorp, but he said Sycamore was “not on the radar screen of Sandy Weil [Citigroup’s CEO and chairman], and I’m sure whoever is doing the cleanup in Colorado is absolutely unaware of this coincidental relationship [with Whitman].”

Richard Howe, a spokesman for Citigroup, said, “Citicorp Venture Capital has had a financial relationship with Sycamore Ventures for many years and still does. Never have there been any discussions between us and anybody at Sycamore on any matter of public policy.”

Whitman’s responses to questions about her potential conflict of interest on the Shattuck cleanup site have changed over time. When the issue was first raised in a Denver Post article last March, EPA spokeswoman Tina Kreisher said such concerns were irrelevant because decisions about local Superfund sites are made not by the administrator but by regional EPA officials. Then, in a Jan. 3, 2002, interview for this story, EPA spokesman Dave Ryan said that Whitman had recused herself from the Shattuck case, but Ryan could not produce Whitman’s recusal form.

In a Jan. 9 interview, EPA’s Martyak noted that Whitman is not obliged to sign an individual recusal form. He pointed out that the federal government’s Office of Government Ethics (OGE) stipulates that a two-step process for government officials — declaring one’s financial interests and avoiding substantial participation in decisions that could affect those interests — is sufficient to comply with one’s ethical obligations.

A spokesman at OGE said separately that officials who wish to document their non-involvement in forbidden matters can either sign formal recusal forms or send letters to colleagues directing them not to refer such matters to them. Whitman apparently has not taken either step. Nor has she placed her assets in a blind trust, another common option for wealthy government officials, such as Treasury Secretary Paul O’Neill and Vice President Dick Cheney.

But Martyak insists such steps are irrelevant, because Whitman hasn’t been part of the Shattuck Superfund deliberations. “The fact of the matter here is that the administrator has not been involved in the decision-making on this case,” said Martyak. “The terms of the agreement [between EPA and Citigroup] on the Shattuck case were reached [in] December 2000, before the administrator was even nominated for this position. What’s in the works right now is simply finalizing the documents on that settlement.”

Kaufman argues that Whitman’s attempted muzzling of the ombudsman is itself participation in the Shattuck case, because it effectively prevents Martin and his office from challenging the agreement the EPA has negotiated with Citigroup.

“The reassignment of the ombudsman’s office limits the ability of the ombudsman to do his job as it relates to the Shattuck case,” says Kaufman. “And Mrs. Whitman knew that at the time that she made the decision. She also knew that she has a conflict of interest on cases that Mr. Martin is presently in the middle of investigating. And that’s a violation of the civil and criminal statutes of the United States.” Martyak, speaking for Whitman, dismisses those charges.

Martin and Kaufman’s lawsuit cites another instance where Whitman may have engaged in prohibited participation in the Shattuck case. According to an internal EPA e-mail of March 16, officials in Region 8 were preparing materials to brief Whitman about the Shattuck cleanup. Martyak says he can’t confirm that Whitman was briefed on the case, but adds that a briefing, if it did occur, does not amount to substantial participation in a government decision.

As for Martyak’s contention that the EPA’s approach on Shattuck was decided before Whitman took office, Kaufman insists “there were lots of options [for Shattuck] being discussed under Clinton. But once she became the administrator, Christine Todd Whitman had to decide if she wanted to give Citigroup the same sweetheart deal. And the first signatures on the [Shattuck] agreement came in October 2001, eight months after Whitman took office.”

The pending agreement between the EPA and Citigroup cannot take effect until it is approved by a federal judge in Colorado, following a 30-day public comment period that begins the day the agreement is printed in the Federal Register, which is expected to happen within the next few days. Martin and Kaufman had planned to organize public hearings in Denver about the agreement and present their findings to the judge. They complained that this would be impossible if they were reassigned as Whitman proposed.

When Whitman announced her reassignment of the EPA ombudsman on Nov. 27, she said the move was intended to increase his independence and improve accountability. Citing a report by the General Accounting Office (GAO), Congress’ investigative agency, that urged greater independence for ombudsmen throughout the federal government, Whitman said that shifting the EPA’s ombudsman from the Solid and Hazardous Waste Office to the Office of the Ispector General would ensure “an effective, impartial and independent ombudsman.”

In a Dec. 27 letter to Sen. Allard, Whitman insists she is committed to maintaining the ombudsman’s independence. But in response to specific questions from Allard, Whitman makes it clear the ombudsman will not control his budget, staff or what cases he investigates. “Assignment of staff resources, including hiring, is a responsibility retained by each Assistant Inspector General,” Whitman’s letter states. As for whether the ombudsman will remain able to select his own investigations, the letter says that “no single staff member [within the Inspector General’s Office] has the authority to select and prioritize their own caseload …”

Sen. Mike Crapo, R-Idaho, says that reading Whitman’s Dec. 27 letter led him to request that Whitman not reassign the ombudsman. “The [Bush] administration has time to delay this decision and work with us in Congress to assure a truly independent position for the EPA ombudsman,” says Crapo, who adds that he thought the EPA bureaucracy tried to muzzle the ombudsman in a previous Superfund case in Idaho concerning the Coeur d’Alene Basin, a mining area suffering from severe toxic pollution. He said he made his request in a Jan. 10 meeting with Gary L. Johnson, EPA’s assistant inspector general.

Aside from the opposition in the Senate, a bipartisan group of House members led by Florida Rep. Michael Bilirakis, a Republican, had urged Whitman before Christmas to withdraw the reassignment plan until congressional hearings could be held. Lawsuits opposing the reassignment have also been filed by local governments in Idaho and Pennsylvania and by a citizens group in Florida. They argue that preventing the EPA ombudsman from doing his job will injure their rights to due process in environmental investigations underway in their states.

“I don’t know of any decision that’s been made where categorically the ombudsman is not going to be allowed to do anything further on Shattuck,” said EPA spokesman Martyak, who argued that putting the ombudsman within the Inspector General’s Office is the best possible location “because the Inspector General is independent of EPA. It does not report to the EPA. It does file a report to the U.S. Congress on its activities. I can’t underscore enough the independence of the Inspector General. That office gets its appropriations directly from the Congress; we have no say in that; it has its own staff, in which we have no say.”

But Martin and Kaufman have tangled with the Inspector General’s Office on numerous occasions. They charge in their lawsuit that their investigation of the Marjol Battery Superfund site in Pennsylvania, with whose contractor, Gould Electronics, Citigroup has a $1.5 billion business venture in Idaho, was “obstructed” in 2001 by Assistant Inspector General Johnson (who is slated to become the ombudsman’s boss in Whitman’s reorganization plan). And last week, the ombudsman opened an investigation into the Inspector General’s Office itself.

“Right now we are investigating the EPA inspector general doing a cover-up in Denver, Colo., on air pollution in people’s homes — not just in Denver but all over the country,” says Kaufman. “That investigation will be closed down once we go to the Inspector General’s Office. Because we can’t investigate the inspector general.”

Martin and Kaufman have tangled with Whitman and Citigroup at least indirectly in at least one other case. The financial giant also owns Traveler’s Insurance Co., which faces numerous medical claims from people living or working at New York’s ground zero in the wake of the Sept. 11 terror attacks. After the EPA performed testing at the site, Whitman announced, “I am glad to reassure the people of New York … that their air is safe to breathe and their water is safe to drink.” But the Washington Post reported Jan. 8 that area residents and rescue workers have suffered an epidemic of respiratory illnesses, possibly linked to toxic exposure at the site from contaminants such as asbestos, mercury and other metals. And on Jan. 9, the ombudsman announced he would investigate the EPA’s testing at ground zero.

“Mrs. Whitman said the air is safe [at ground zero],” says Kaufman, the ombudsman’s investigator, “when in fact the documentation of test results show the air has not been safe and people are being made sick. All of the two dozen cases that we’re doing around the country will now lose a public advocate because Mrs. Whitman wants to protect the financial interest of the Citigroup Co. that she has had a longstanding and ongoing financial relationship with.”

Regardless of whether Whitman tried to protect Citigroup specifically, Martin and Kaufman’s defenders say she’s clearly acting to muzzle two staunch advocates for the environment, who’ve been a thorn in the side of industry before. When she was New Jersey governor, Whitman eliminated the state’s environmental ombudsman and sharply reduced related regulations, critics say.

“Administrator Whitman says she’s making this reassignment in the spirit of the General Accounting Office report,” said Tom Devine, legal director of the Government Accountability Project, a public interest group in Washington that is representing Martin and Kaufman in their suit against Whitman. “But nothing could be more contradictory to the report. Instead of beefing up the ombudsman, she has abolished the concept. Thanks to Judge Roberts’ ruling, Whitman’s fait accompli has been thwarted.”