Late last week, the hot rumor going around all the embassy clubs in Islamabad was that it was possible to fly to Kabul on a United Nations world food program transport. At the bar, when people talked about it, the words "flight" and "plane" were said with such reverence that it seemed like the speaker was talking about a personal religious ritual. What it meant was, if you had the money and the right cellphone number, driving across the treacherous Khyber Pass through dangerous tribal areas was no longer necessary.

If you are going to Kabul by car from Pakistan's capital, the first big stop is Peshawar, just at the foot of the Hindu Kush range. It's a smuggler's clearinghouse for unrefined opium and everything else coming into and out of Afghanistan. Next comes the long climb through the Khyber Pass, a place famous for the 19th century massacre of an entire group of British soldiers by Pashtun fighters, who, with great media savvy, left one man alive to tell the bloody story. Jalalabad is just on the other side of the mountains, in a long valley of green fields and shade trees.

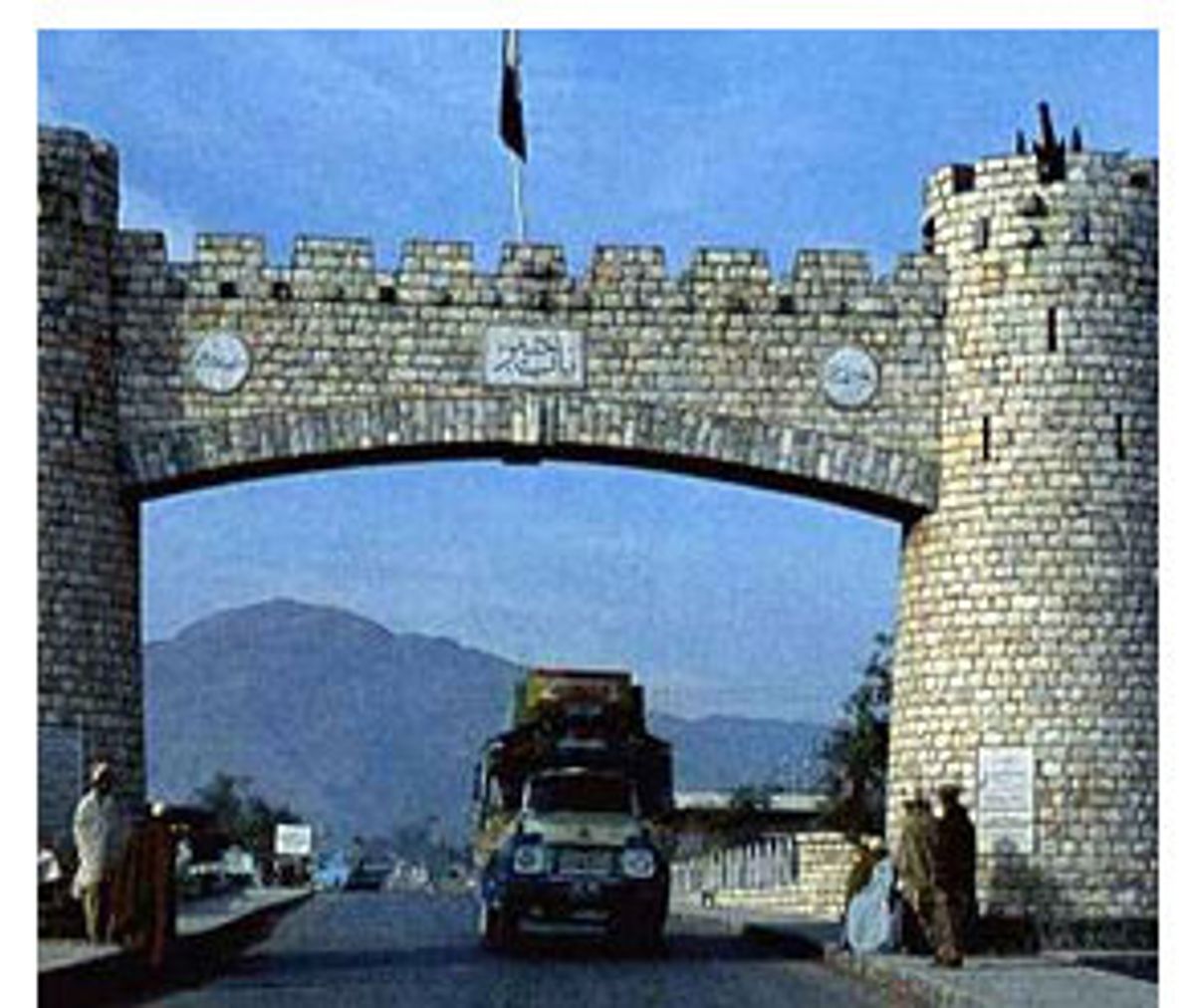

After that is the Kabul-Jalalabad road, made notorious when four journalists were murdered there in November. It's a bit better now, but all driving has to be done during the daylight hours, because trying to go anywhere in the dark is asking for it. But even before that, the last checkpoint before arriving in Afghanistan is Torkham, and here the traveler must leave behind everyone who is working for him. You can't bring in a driver or a translator, even Afghan nationals. In November, a British journalist told me that his translator had come across from Tajikistan and received a brutal beating for it, but at least he was allowed in. At Torkham that's not even an option. Transport cartels now control the Afghan side of the border, and new arrangements with drivers and translators associated with the cartel have to be made once you cross the frontier. Hajji Kadir, the brother of the late Abdul Haq -- who was ambushed coming back into Afghanistan at the start of the war -- is now the governor of Nangharhar province, and he gets a substantial piece of all this border action.

The U.N. food transport flights would make all of this just a bad dream, of course. But the first flights were full, and then on Sunday they were canceled due to bad weather. It rained, but nobody could understand why the planes weren't taking off, so there was plenty of drinking at the clubs, along with bitching and moaning. Gin-and-tonics took the edge off the feeling of being stranded, and also helped quell the thought of what would go down if India invaded Pakistan. Both countries possess starter nuclear missiles, intermediate range things with names like Prithvi and Ghauri which will go just far enough to wipe out a major city. Some of them were almost certainly hauled up into the passes of the Jammu Kashmir, close to the Line of Control, where there are at least a million troops ready to go at each other with knives or whatever else is handy. Islamabad wasn't all that far away from those mountains.

On Friday, a day before Musharraf gave his big speech cracking down on Islamist militants and trying to placate India, I asked the the U.S. Embassy press attaché, Mark Wentworth, if he thought India and Pakistan would go to war. He looked across his desk for a second and said, "I don't know. Do you?" I started in on how it seemed like even odds, how the U.S. could possibly help to avert something truly evil, but he wasn't listening. The TV was on and a military jet was taking off and it had hypnotized everyone in the room.

Then on Saturday, Musharraf gave his speech to the world, a long, plaintive desperation-tinged rant, in which he gave up on the principles of an Islamic state. The roundup of extremists got most of the media coverage, but the speech did more than launch that. Buried in his talk there was a line about how mosque loudspeakers could no longer be used for angry sermons, and how any mosque that broke the rules would have its privileges revoked.

Musharraf talked to his countrymen as if they were children playing with dangerous toys, but almost everyone I spoke to about it said that he had done the right thing, that he was doing his best for his country. A Pakistani citizen at the U.N. club said that the speech was good, but that we had to wait and see what the mullahs would say.

"Are they going to be angry about it?" I wanted to know.

"Oh yes, they will be very angry," the staffer said, and laughed.

Still, the India-Pakistan standoff continues. It goes like this: Musharraf is afraid of losing a war, while Vajpayee is afraid of losing an election. It's hideous politics that makes rational people want to drink. I kept thinking about what India named her first nuclear test in the 1970s. It was called "The Smiling Buddha."

On the day of Musharraf's speech, a small group of Pakistanis were demonstrating for peace. They were breaking the law. In the News, an Islamabad paper that morning, there was a microscopic blurb about "Section 144" being imposed in the capital, which, among other restrictions, "prohibits all kinds of gatherings of five or more persons, including processions, rallies and demonstrations at any public place within the limits of Islamabad." So at the appointed time, we went out to Aabpara Chowk, a busy intersection, and waited. But we saw only police with riot shields. Across the street, on the opposite corner, a few people were standing around; then a few more arrived, trickling in with handmade signs in Urdu and English. The demonstrators held their signs up to the traffic.

Aasim, the leader of Citizen's Peace Committee, said that they had a much larger demonstration planned, but that the Intelligence Bureau had called him and told him he'd better not do it, so he told everyone to stay home. What we were seeing was the organizers themselves. As Aasim and I talked, a man with a three-day growth of beard came up to listen. We shook hands, and Aasim leaned over to me and said in Oxford English, "He's the secret police."

"Really?"

"Absolutely." Aasim said.

The three-day growth and the dead eyes, I gradually realized, was a kind of Pakistani secret policeman's uniform. The hotels where the foreigners were staying, I soon noticed, were crawling with them.

After three more days of stagnating in sleepy Islamabad, it was clear a flight to Kabul was going to remain a lovely dream. It was time to go to Peshawar and drive to Afghanistan through the Khyber Pass.

Shares