It was Monday morning and time to go to back to Afghanistan. Fabled United Nations flights to Kabul were either booked or canceled or vaporized by Secretary of State Colin Powell's impending visit to Islamabad's backwards airport. That meant that it was time to drive, which was fine, anything to be in motion and get out of the purgatorial Best Western. During every news cycle for the past two nights, the BBC was running clips of the blind lion in the Kabul zoo, zooming in on his empty sockets, intercut with a sequence of a noseless bear, another helpless victim of the Taliban, so said the report.

Afghanistan's weird radiation was coming over the mountains two hundred kilometers away. Had it been a sound it would have been a low electrical hum.

Quick, what is the difference between Pakistan and Afghanistan?

Pakistan is a country.

Outside the Best Western, Nizar had the cab ready at exactly the appointed time and the moment he peeled out of the driveway, things began to look up. On the side of the road there were hundreds of young men milling around doing nothing. Further on, as the country opened up a little, the mountains slowly rose into view in front of us. Peshawar is a smuggling city, and it is everything Islamabad is not. There are weapons markets, jewelry markets, hashish markets, anything markets. If the proprietor doesn't have your gun, give him time and he will make it for you. Some bazaars are supposedly closed to foreigners, but that could mean anything here.

Is this toy safe for children ages 3-7, sir?

No, ma'am, that's a grenade.

There is an old city, a twisted warren. Old cities like this one and Barcelona's Barri Gotic and all the others are always called warrens, because they are overcrowded hives, and this is what gives them their edge. I dumped my stuff in a room at Peshawar's Pearl Hotel, and started walking toward the Moghul fort, looking for the bazaar, but kept blowing the map directions, getting hideously turned around and finally located a street that fed into the great central bazaar and went in just for a look.

On the Qissa Khani, the old street of story tellers, a runner brought tea with milk and sugar, and a few minutes later a madman paraded down the street shouting, windmilling his arms, and the whole population of the street poured out of the buildings after him and shouted one mysterious sentence until it became a roar. It was over in seconds. In the old city, that strange telescopic time warp hit; when I next looked at my watch, it was dark and three hours were gone.

Back at the Pearl, when the uniformed floor guard asked if everything was alright, I explained that I had a small problem that involved having to go to Afghanistan. That problem was not really a single difficulty but a chain of headaches, like a distinct lack of understanding of the necessary permission letters and passes, bribes, and fixers necessary for the crossing. Add to that the ridiculous transport mystery, the inevitable lodging mystery, the armed guard hassles. I knew banknotes were getting ready to leave my wallet like startled birds, all twenties and fifties, but once started, it can't stop because the deal gathers momentum at each step. Hiring a fixer is also vital because the supplicant, who needs juice with the authorities, arrives with absolutely no juice.

"One moment, sir."

Four minutes later the shift supervisor appeared, a man named Shafraz, dressed impeccably, exhibiting signs of dwarfism. He came in, said he knew a man who could help and would it be OK if he used the phone. Shafraz made a quick phone call, speaking in Pashto. Exited quietly and promised to be back. Forty minutes later, Shafraz reappeared with a tall Pashtun in a flak jacket and introduced us.

"Here is Manzoor, he can take care of everything, please." When I shook Manzoor's hand, it was a little warm. Then, Shafraz left us and said we could work things out together.

Manzoor wanted to see my entire file of papers, accreditation and visa documents. When he looked at my writer's union card, he said, "What's this?"

"My writer's union membership card."

"This is nothing, this is a coupon." Manzoor waved it in the air to demonstrate its corrupt and insubstantial nature.

"You're hired," I said.

Manzoor told me to be ready at 9:30 the next morning for the pilgrimage to all the various competing agencies and offices, and it seemed like bad luck to ask which of them exactly were on the list, because the mere question would illuminate the thousand ways the process could go tits up.

Our first stop was the Press Information Office, then the North West Frontier Province Home and Tribal Areas Office, then the Khyber Political Agency office, and finally, as a grace note, the Afghan Embassy for a safe passage letter, from the family of Abdul Haq. The Pakistanis had kept the entire bureaucratic effluvia of the British Empire without changing the smallest detail, and the process took a respectable three hours, plus $40 for the Khyber Pass bribe.

In the car, Manzoor wanted to know something.

"Would you mind if I didn't come with you to the border crossing at Torkham? My malaria is acting up. The driver can take you there without me."

"You have malaria?"

"Yes, it is bothering me, and I don't feel well." He was petulant.

"No way. You are coming with me right to the bitter end."

"OK, no problem."

It didn't feel right to head to the frontier without a translator.

On the way out of Peshawar, a young boy came up to the window of our car with a steel cup full of burning herbs. He blew the smoke into the car. In Tajikistan, it was explained to me that the smoke had curative powers, a tradition which dates back to Avicenna, the 11th century Persian Muslim physician and philosopher. Poor children move around the streets of these places, offering the cure in return for alms. These trips across the Afghan border are marked with the appearance of these street curers, making it a ritual of departing for the war zone. It's happened to me twice so far. Once in Dushanbe and now in Peshawar.

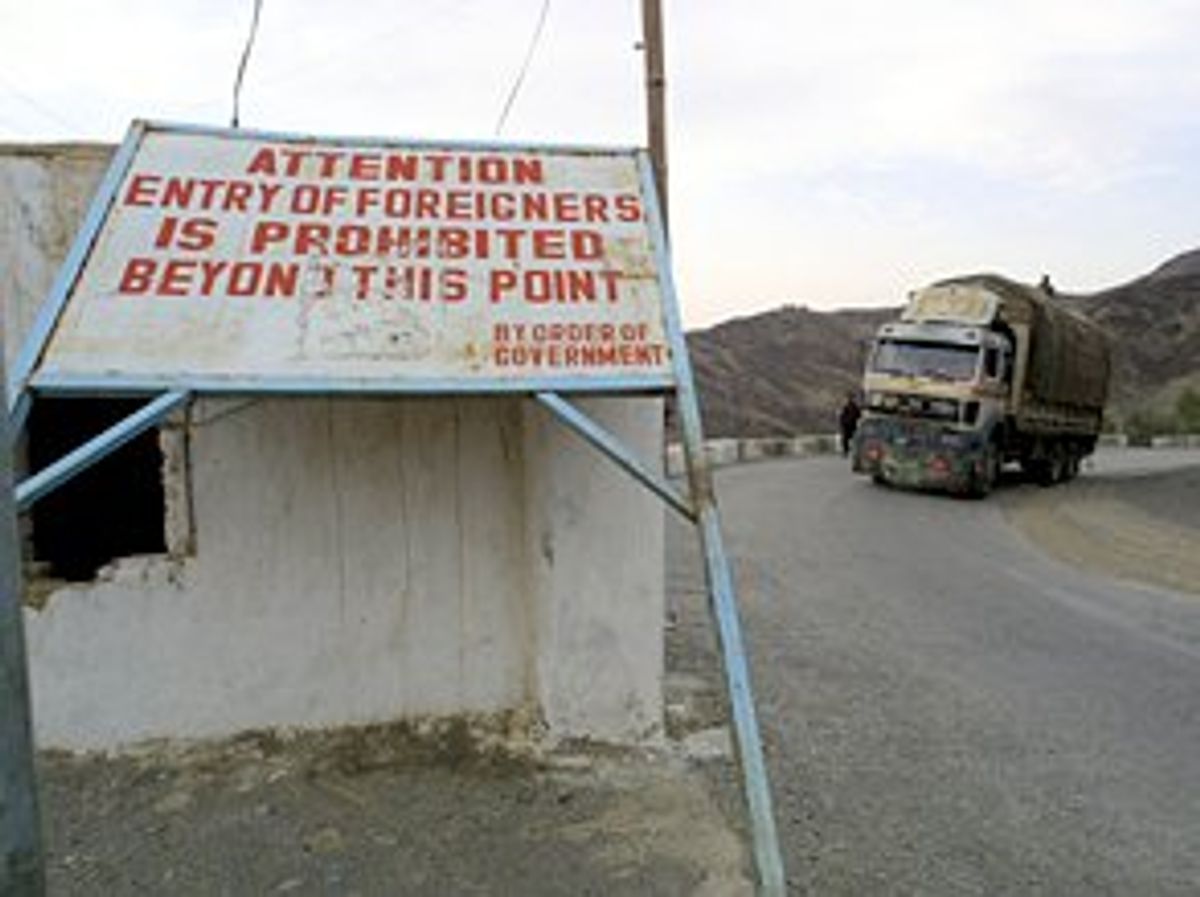

Outside the city there's a police gate with a sign that reads, "No Foreigners Beyond This Point." Manzoor handed over the first letter and we kept on going up into the hills. Tons of material moves across the border, day in and day out, and I got the feeling that I could have taken a bus to Afghanistan for a hundred rupees, or just paid a bribe to be smuggled cargo. It's an unsealable border, despite Pakistan President Pervez Musharraf's assurances to the contrary, and everybody knows it.

We were in the mountains now, which are more jagged than the smooth lunar hills of northern Afghanistan. The Khyber Pass is covered with rocky spurs and dotted with small watchtowers, leftovers from the Empire. As we approached the Torkham crossing, Manzoor leaned over and explained that he thought the Taliban had a point, and that Musharraf was making a big mistake with the mass arrests of religious party members. I asked him what he thought was going to happen, and without hesitating, he said, "The next war is going to be here."

After the last checkpoint we drove into Torkham, a frenzied tangle of low buildings, buses and freight trucks. People moved back and forth across the border between Pakistan and Afghanistan without going through customs. Manzoor, our driver and the Pakistani armed guard that the government had insisted on, waved goodbye and wished me luck. Then the Pakistani customs official stamped my passport and I walked down the hill, past a metal barrier, into Afghanistan.

Shares