It is the climax of the movie, and easily one of the most powerful scenes in the history of cinema. Luke Skywalker, facing Darth Vader at the end of "The Empire Strikes Back," losing both the battle and his hand, crouches precariously on a small bridge over a seemingly bottomless pit. Vader picks that traditional bonding moment to inform Luke that he is actually Luke's father.

Luke's whine of disagreement is understandable: His dad is a genocidal planet-destroying maniac, he just lost one of his more useful evolutionary tools and, let's face it, Luke generally whines about everything anyway.

Darth's revelation takes all the film's previous insistence on the easy dichotomy of good vs. evil and throws it, well, into a bottomless pit. Evil can spawn good, and good can become evil, and the lines in between are fluid and ever changing. Suddenly the "Star Wars" universe is much more real and interesting.

It's all too much for both Luke and "Star Wars" founder George Lucas to handle (they're really the same: Luke Skywalker, Luke S., Lucas), so Luke, too, leaps into the pit to his "death" -- although he instead follows the path of his lost hand -- and gets sucked into some kind of venting chamber to be safely deposited underneath Cloud City for easy rescue access.

What a scene! What a moment! What the fuck? I was 8 and a half years old. And in the debates that ensued among my 8-and-a-half-year-old peers ("Is it true?" "No way!"), we discussed the nature of good and evil and moral ambiguity in ways that made us sound more like Old World rabbis than third-graders trying to figure out how to play with our action figures.

And why shouldn't we? Passion for "Star Wars" is like passion for any religion. Some in Australia are even fighting with their government to have "Jedi" labeled an official religion in that country's census. And I was a budding acolyte. Every night at bedtime, snuggled in my "Empire Strikes Back" sheets and sleeping blanket, I would imagine myself up on that bridge, confronting not just Darth Vader but all of the universe's complexities. I knew there would be no easy answers -- at least not until the third "Star Wars" film -- an agonizing three whole years away.

But I knew there'd be answers. The characters -- and thus the makers -- of "Star Wars" were my heroes. They wouldn't let me down.

I was so hooked.

Twenty years later, I find my mind has wandered back to Cloud City; same bridge, same pit. Again, I imagine myself as Luke, only now it's George Lucas wearing the heavy-breathing Darth mask, standing over my head. And he's reaching out to me, holding some crappy "Pod Racing" video game, contemptuously chanting: "Who's your daddy? Who's your daddy?"

At that moment, I think about how "Star Wars" and Luke's tale changed my life. And then I think about Jar Jar, those damned Ewoks and how diluted the original impact has become. The "Star Wars" of my youth, like my desire to purchase action figures, left me long ago. What's left isn't bad -- but while I'm not too old to enjoy a fun movie, I prefer my motion pictures to do something other than have pictures that move.

And so, like Luke, I decide to let go. I leap into the pit -- but not to my doom, because I know there is a vent down there. And that vent's name is Peter Jackson -- director of "The Lord of the Rings."

And as I wait for my ride beneath Cloud City, let me say it for all to hear, and later e-mail me angrily about: "Lord of the Rings" is better than "Star Wars"!

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

It's a tough call to make. Both films -- and both phenomena -- are worthy ways to spend your cinema dollar. Both films are transcendental -- defying genres and expectations, taking the viewer to struggles in fantastical lands and in the process illuminating the struggles within ourselves. That illumination has inspired legions of fans on both sides. J.R.R. Tolkien's "Lord of the Rings" has been part of world consciousness for generations, inspiring artists, writers -- including George Lucas. "Star Wars" defined modern fantasy filmmaking. (There is no science and, therefore, no science fiction in "Star Wars.") The way Lucas went about making "Star Wars" and its sequels -- from the storytelling and special effects to the marketing -- is nearly as much an influence on Jackson as Tolkien.

In her recent Salon article "'The Lord of the Rings' vs. 'Star Wars,'" Jean Tang takes the view that "Star Wars" is the superior effort. She states, quite well, that the simplicity and humanity of "Star Wars," which led to greater accessibility and ultimately a greater phenomenon, made it superior to the dark, explicit and increasingly humorless "Lord of the Rings."

Her citing of plot and character problems in "LOTR" is interesting -- although one could easily catalog the same of "Star Wars," if not more so. I tittered at the supposedly fearsome but easily addled storm troopers when I was 8, yet still overlooked that for the greater film at hand. And in that spirit I'll also overlook the greatest problem with Tang's article: Why on earth compare these two films?

OK, they tell the same story for starters. In his landmark 1949 "The Hero With a Thousand Faces," mythologist Joseph Campbell -- who would later use Luke Skywalker as an example for his theories -- writes of the "monomyth," in which a hero leaves the average world for a supernatural one, defeating foes decisively, growing in the process and returning from this "mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man."

That could be Luke or Frodo Baggins, from "Lord of the Rings," sure. Jesus, Moses or Mohammad, too. Even the fun but hopelessly derivative Harry Potter has a place in the monomyth.

So who does it best?

During an online debate of this very contentious issue, a friend of mine summed it up this way: "'Star Wars' was a pop-culture synthesis which is now being eclipsed by one of its major source materials."

Yes, my friend talks that dorkily. When it comes to "Star Wars" and "LOTR," we all do. We're paying members of the religion. That's why one can't just be content to say: "Both movies are fun. Let's pay attention to the Enron scandal."

To a "Star Wars" or "Lord of the Rings" fan, this is much, much bigger than Enron.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

As stories, and as films, it's almost ridiculous to compare them -- especially now. After all, "The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring" is just the first film of a trilogy, devoted to preserving the integrity of books that everyone has either read or is currently pretending to read. "Star Wars," on the other hand, is an original story, beholden to nothing but George Lucas' vision, and, forgetting the current prequel trilogy, it's finished.

Comparing just the first movie of each trilogy is equally futile: The first "Star Wars" (now known as "Episode IV: A New Hope"), which Tang mostly relies upon, is a stand-alone film. When Lucas made it, he had no idea of its success, or that he'd be able to make his grand vision of three, or six, or 12 films (depending on which of his early interviews you believe). So "Star Wars," the first film, ends.

"The Fellowship of the Ring" does not end. It doesn't even have a cliffhanger -- everyone is already falling off the cliff at film's end. And because it's part of a trilogy, the movie introduces quite a bit of material that isn't going to become particularly useful until later in the series. Arwen, the elf played by Liv Tyler, offers an elvish ex machina rescue, as well as a foreshadowing tender moment or two -- but depending on how Jackson follows the books, her role isn't really interesting until the films that are still to come. And you know those scenes of goblins pulling the trees out of the soil of Isengard? That'll piss off more than the Middle-earth Sierra Club later on.

For this reason, when I say I'm comparing "Lord of the Rings" to "Star Wars," I'm really comparing it to "Star Wars" and its first sequel, "The Empire Strikes Back." Both end on a moment of total transition, both require the creators to plan ahead and to make conscious choices in favor of the story -- not just how audiences want movies to progress. I'm also doing this to be fair; to include the entire "Star Wars" oeuvre would mean bashing the unsatisfying "The Return of the Jedi," Jar Jar Binks and a failed 'N Sync cameo to come, and that's just shooting fish in a barrel.

Looking at the story lines, and the storytelling, you see the potential dangers with each film. The epic plotting of "The Fellowship of the Ring" threatens to ruin the movie more than once. Under the auspices of a lesser director, watching the film could be like watching a freight train go by. This happens, then this happens, then this happens, then this happens -- as our characters are tossed from action scene to action scene. Tolkien got away with this in the books because his writing was extraordinarily boring. You could never really tell you were being overstimulated.

But Jackson's ability to explain in simple ways why his characters go from place to place saves us from that fate. There is a clear goal, and every set piece builds on that goal. Additionally, the land tells the story as much as the characters do: Middle-earth is changing, the old ways are passing and every landscape shot alludes to these changes.

"Star Wars" also takes place during a time of transition. Every battered and rusty space transport implies a history of past battles and other stories. We don't get these deep stories in the "Star Wars" series. Our heroes blithely go from place to place, peril to peril, without the same clear goals. One of the most watchable aspects of the "Star Wars" plots is the focus not on the larger stories, but on the main characters, who affect the big picture, without really being a big part of it. The Rebel Alliance is always just about to start a new mission whenever Luke or Han Solo reach a base. There's a larger tale going on, one of tyranny, rebellion, political and social movement. But "Star Wars" focuses on the characters, not on that story. So, it makes for easier viewing than "Lord of the Rings," but it's not necessarily as compelling viewing.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

Still, the heart and soul of both films is character, not plot. After all, we remember "Star Wars" not as the tale of a vast and unmanageable empire, but as Luke's transformation from Toshi Station mall rat to mystic Jedi knight. Frodo Baggins, the hobbit hero of "The Fellowship of the Ring," also yearns for adventure. He idolizes his weird Uncle Bilbo's adventures, adventures that could take him from the boring but idyllic life in the Shire.

But when a wizard named Gandalf shows up with an all-important adventure that has to start immediately, what does Frodo do? He panics! He goes only reluctantly, always under the impression that he'll get to go home once the first step is through. Frodo doesn't just whine like Luke, he winces, cowers and weeps and is pretty much uncool through most of the film. And as such, the hobbit Frodo -- unlike fun, daring hero Luke Skywalker -- becomes more human than the human Skywalker.

Luke is what whiny dorks daydream they would be. When adventure comes calling, they'd sign up immediately, and succeed totally. Frodo, on the other hand, is the way we are: comfortable in our inadequate lives, yet terrified of change. I cry like a baby if the candy machine at work is on the fritz. If I were being chased by some spectral hooded spirit out for my blood, I'd likely go catatonic.

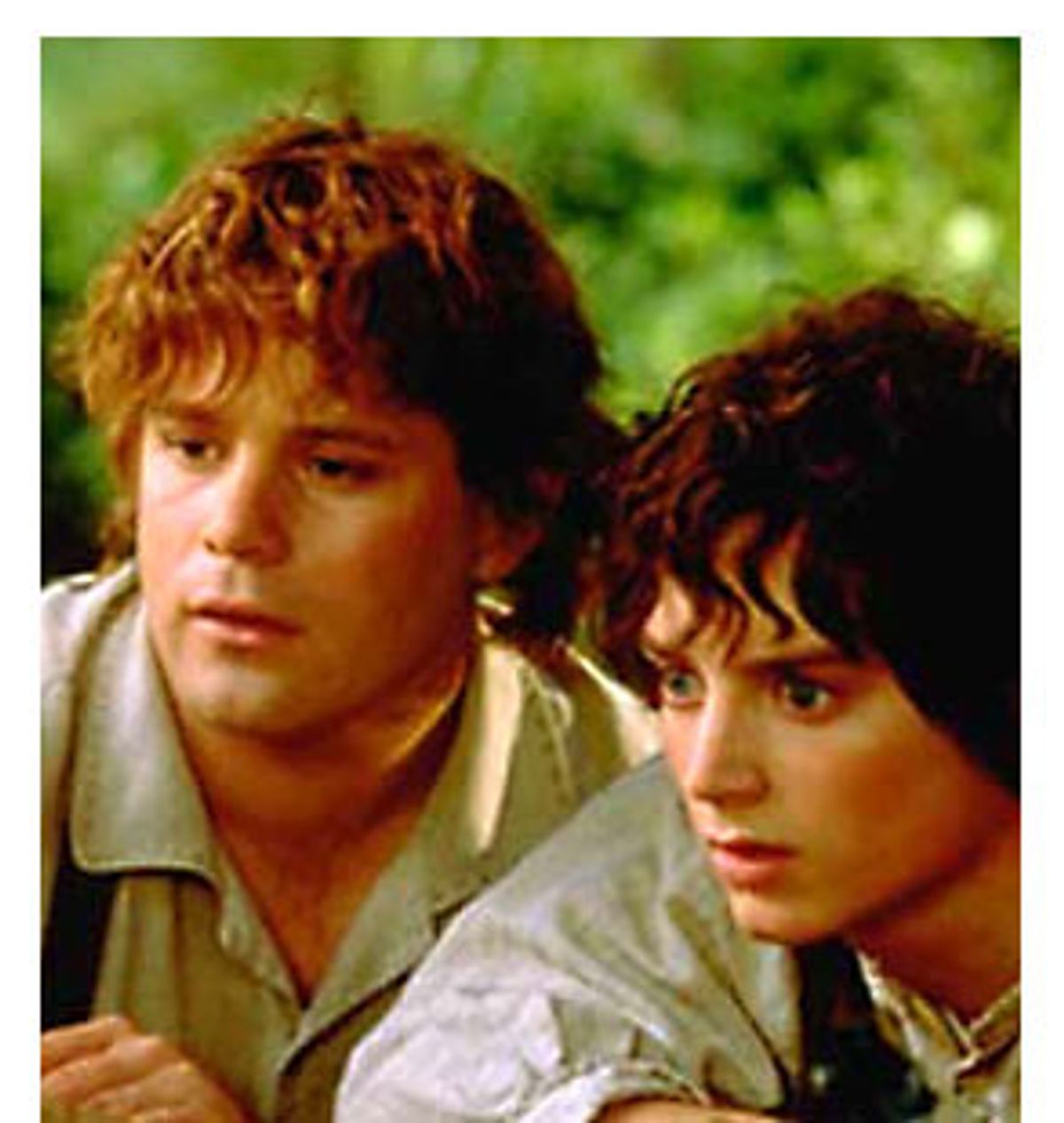

Despite his fears, Frodo goes on his quest -- after all, it wouldn't be much of a monomyth or movie if he stayed, but you never lose the feeling of trepidation that Frodo has. Even if there weren't computer-generated baddies stabbing him at every turn, you know he'd still be bummed about leaving town. His companion Sam is quite vocal about his concerns. He may dream of the outside world, but the reality of going there is awkward and horrible, and it's not often you see an action-adventure film that details homesickness as a movie-long affliction.

This is not pretty heroism. No one daydreams about feeling obligated to go on an adventure. You want to be like selfish, shallow Luke, who goes because ... well, it's the coolest thing to do. His Uncle Owen and Aunt Beru are murdered, and for a while he even believes his father was killed by Darth Vader. Yet avenging their deaths is never on his mind. Their doom just makes it all the easier to cut ties and take off with the first trained British actor who passes by.

But in real life, it's obligation that drives history's heroes, not boredom. Gandhi didn't start a movement because he grew weary of cricket. Lincoln didn't seek the presidency because of log cabin fever. That Lucas was never able to give his characters similar motivations is just a symptom of a shallow film.

But shallow is fun -- you need only compare each of the secondary characters. If you're looking for entertainment rather than case studies in human frailty, then by all means, get that "Phantom Menace" DVD. It's not just Luke vs. Frodo: The "Star Wars" characters are who you'd like to be; the "Lord of the Rings'" various wizards, elves and hobbits, by contrast, are who you are more likely to be in similar circumstances -- especially if you're like me, and are already short and have hairy feet.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

And in the end, it may be that lesson in responsibility that makes "The Lord of the Rings" such a great film. Both "Star Wars" and "Lord of the Rings" are focused on the cartoon battles of good vs. evil, but "LOTR" takes it a step further and says we all have a responsibility to do what we can in that battle.

I cried during Gandalf's speech to Frodo when he speaks of the responsibility to bear great things, and the strength required to succeed. No one seeks these burdens, but those who receive them must rise to the challenge. It's a practical message in the most absurd setting, and it's hardly a salve in the post-Sept. 11 world. There's no "it'll be OK" tacked onto the end -- and we have no way of knowing if happy endings are in store for the future. There are no similar guarantees in the real world.

Though I've read the book, and pretty much know what happens to the ring, I have no such preconceived notions toward the real world. Will I ever lose the sick-to-my-stomach anxiety I still have every morning when I pick up the paper or see an airplane over my head? Will it get worse today? Will we accidentally bomb the wrong people again, or will we ourselves be bombed again? What is my role, what can I do, and if MSNBC says that Americans are recovering, why am I still nervous when I get in an elevator?

So, I go see a movie. And though I wish I could be a hero, with old man Kenobi whisking me away to a place where I can join an easy good vs. evil fight -- I know it's not that simple. So I have old man Gandalf telling me that it's not for me to choose my burden but just to choose how to bear it. And I have Frodo grotesquely weeping to remind me that as far as burdens go, simply getting up in the morning isn't too bad.

"Star Wars" broke out of its formula only once; that classically Oedipal scene in Cloud City is the pinnacle of it. But like Luke's hand, it dropped into a pit, and the series returns to easy-to-stomach simplicity. As if to drive the point home, the bad guys are ultimately defeated by warrior Care Bears.

That's not a bad thing. After all, these are only movies. And when I just wanted a movie to be a place where bad guys lose comically and you could go from bored teen to messiah in just three movies, well, "Star Wars" fit the bill.

I don't remember what I went into "Lord of the Rings" expecting, other than an unsatisfying image of a Balrog, but I came out with so much more. The film transcended itself and took me to a place I hadn't yet been ready to go. This absurd film of hobbits and dwarves and goblins and orcs said enough things to me about living a real everyday life in 21st century America to make it seem truly possible.

So maybe it's not so much that "Lord of the Rings" is better than "Star Wars," but that "Lord of the Rings" is somehow more real than "Star Wars." And right now, that's what I wanted.

There's a scene at the end of "Fellowship of the Ring" -- easily one of the most powerful in the film, and one that perhaps one day will also take a throne in the annals of cinematic history -- when Frodo's devoted friend Sam risks drowning rather than let his friend head off to certain death alone. In the books we know Sam fears water -- but the movie doesn't delve into that. Jackson focuses instead on Sam's simple devotion: Sam wades into a river after Frodo's boat. Underwater and close to death, we see Sam go limp, until Frodo's arm juts down, grabbing Sam's wrist. There's a pause, then the two hands clasp.

Sam isn't alone in being pulled up from the brink. We were, too. George Lucas knows how to make money better than he does how to make films, and it's clear at this point that Lucas doesn't give a damn about the depth some of us wanted to give to his best movie. It was just a movie, and we should just shut up or move on.

And the nice thing is now we can. Because it's obvious that Peter Jackson is as earnest as, well, Luke Skywalker, and Jackson wants his films to be more than that.

Shares