Before you crack this book open, close your eyes and let your imagination roam into the eons to come. Maybe pets will have evolved to do housework. Maybe real food will no longer exist. Maybe humans will have developed a handy fertility switch, to be flicked on only when we want babies. A title like “Future Evolution: An Illuminated History of Life to Come” inspires fanciful musings, no?

Well, this book isn’t anything like that.

Peter Ward, a geology professor at the University of Washington in Seattle, is not really a details man. Even in the chapter dealing with the future evolution of humans — and let’s face it, that’s what we shallow laypeople are interested in — there’s little to really set your heart aflutter. He speculates vaguely that the races may merge, yielding “a universal brown-skinned future.” That’s nice. And that we may be genetically engineering our offspring. Well, yes. The one really intriguing suggestion he raises is that we should somehow manage to stop eating and become solar-powered, but he expends a mere paragraph on the idea.

Despite what its title may imply, this book is concerned more with the process of evolution than with its specific results. Almost half the book is taken up with evolution’s historical record, and the other half is basically a framework for how it will carry on.

But Ward’s Big Idea is a fascinating one. (Good thing, too, as this isn’t the first book he’s written on the topic.) Unlike the doomsayers out there, he doesn’t think there’s another mass extinction looming. Rather, he’s convinced it’s well underway, and that the worst is already over. Most of the big mammals that are going to die off already have. Among those no longer with us are the mastodons, the mammoths, the saber-toothed tiger, the giant short-faced bear. “It is visible in the rear-view mirror, a roadkill already turned into geologic litter — bones not yet even petrified — the end of the Age of Megamammals,” he writes.

History has taught us that mass extinctions like these — especially of large beasts — usually give rise to exciting new species. The Permo-Triassic extinction 250 million years ago lost mammal-like reptiles and gained dinosaurs. The Cretaceous-Tertiary extinction 65 million years ago extinguished the dinosaurs, making way for mammals. But if you’re eagerly awaiting the new exotica, you might be disappointed. Ward thinks that most of the new species to spring from this round of death have already sprung. They are mostly farm animals, transgenic plants and drug-resistant bacteria.

And while human beings had a hand in the demise of the megamammals, and even in determining which among the new species would survive, we aren’t going to die out in some kind of earthly tit-for-tat. Indeed, Ward describes us humans as “functionally extinction-proof.” We’re smart, for one thing, and adaptable. Chances are, says Ward, humans will be around to see planet Earth through to its end.

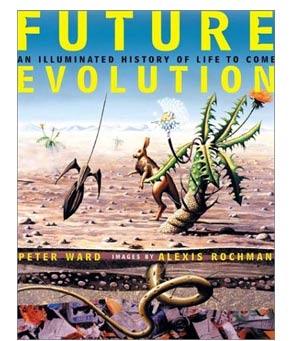

A particular pleasure of the book is the futuristic artwork that accompanies the text. In glowing color, we are presented with everything from square tomatoes to kangaroo-like rats. Artist Alexis Rockman adds this delightful dimension to the book.

Ward, for his part, is a very capable writer. His words are well chosen and carefully polished. Occasionally he’s downright eloquent, as here, on the impact of cities:

“Our plane lifted from the lushly verdant Yucatan on a luminous day, and we flew over a starkly visible Mexico. The flight was not very long, and a vista of mountains and forests passed far beneath us. Eventually I spotted a distant mountain, larger than the others, and as we approached I was filled with wonder. Never had I seen a mountain like this before, perfectly dome-shaped, brown in color, impossibly tall, a vision that enlarged and degenerated into implausibility. Our pilot headed straight toward the summit of this great mount, and just as we were about to crash into it, I realized what it was: the air over Mexico City, a mountain of pollution covering the huge sprawl below.”

Ward’s early chapters, highlighting the two above-mentioned extinctions as well as the current one, are authoritative and clear. However, when he strays from his areas of expertise, as when writing on the future shape of man, I found it harder to trust him. He relies too heavily on single sources to flavor his predictions, and too often those single sources are writers of outdated popular science books.

Ward gets in a muddle on the issue of intelligence, for instance. First he struggles a bit to define it, then decides it’s irrelevant to do so. He summarizes two theories on how human intelligence evolved in a paragraph each. Then, borrowing heavily from a book called “The Gene Bomb,” published in 1996 — so, probably written around 1994, years before some of the biggest leaps in human genetics — he raises the possibility that we could get dumber and more mentally unstable. Ward doesn’t exactly buy the idea that we’ll be less intelligent, but he nevertheless reiterates the suggestion by the author, David Comings, that we are unwittingly passing on the genes for behavioral and mental disorders.

According to Ward, Comings makes that stale old argument that people with behavioral and mental disorders get pregnant earlier and more often, thus sullying the gene pool — a sort of “unnatural” selection — while “intelligent” people go to university and breed less. Comings apparently suggests that the former is true of people with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). But do people with ADHD really reproduce more and at a younger age? How many studies have been done on that question since the disorder was first recognized and included in the DSM, the bible of mental disorders, in 1980? And are people with ADHD really less intelligent, or do they just perform less well on standard intelligence tests because of their inability to concentrate?

These are but a few examples of factoids I would have liked to see referenced. But, alas, there are no footnotes. Has genetic engineering of plant species really yielded “spectacular dividends in terms of crop yield”? Exactly which “further work” has found that “depression, addiction, and impulsive, compulsive, oppositional and cognitive disorders” may be “coded on only a few genes”? How can I be confident in what Ward is saying if he doesn’t tell me where the learned ideas come from?

In a way, I have to admire Ward. He builds most of his case on the science as he knows it. He is well aware that a lot of readers are clamoring for a sensationalist life-after-man story. He even includes a charming anecdote of how the BBC asked him to be a scientific advisor for a television series on the future of evolution — with one catch. The future of evolution, they had decided, would not include humans. Needless to say, he politely declined.

Ward’s book is fun, insightful, educational and bold. Sadly, for me, there was just a tad too much Evolution, and not enough Life to Come.