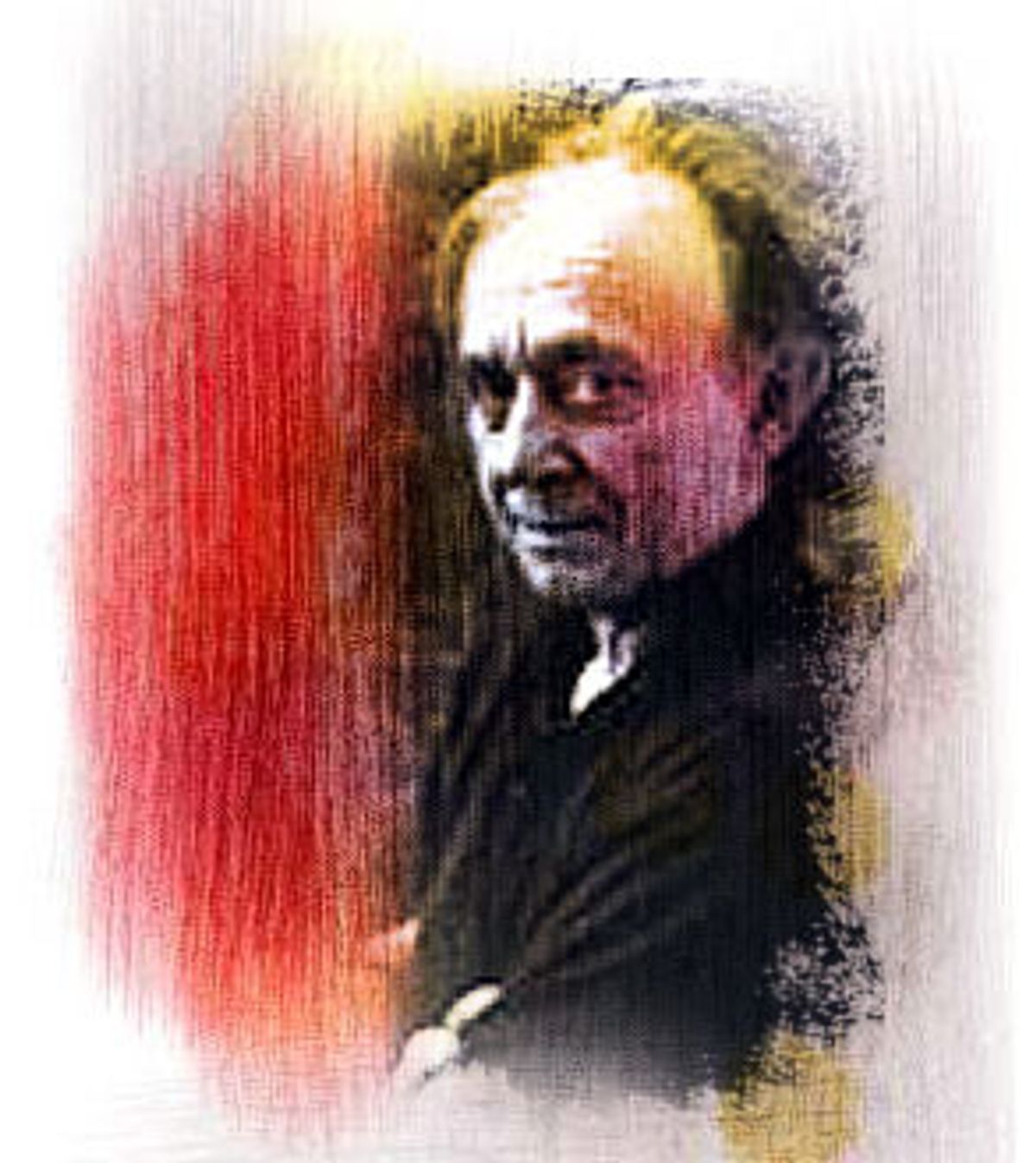

Though he gets less press than, say, Scorsese or Spielberg (or Brett Ratner or Tom Green, for that matter), Frederick Wiseman for over 30 years has quietly forged a lasting impression of our nation on celluloid. The Cambridge-based documentarian, along with D.A. Pennebaker and the Maysles brothers, is a pioneer of cinéma vérité. In its early years, cinéma vérité consisted of more than just its stylistic trappings (grainy footage, hand-held camera work and natural sound); it sought to reveal the underlying truths of situations by capturing the unscripted action of real people. Think of the vérité filmmakers as the very disappointed stepfathers of "The Real World" and "Cops."

Wiseman, whose works include "High School," "Hospital" and "Public Housing," began making films while working as a law school professor in 1967. "Titicut Follies," his searing exposé of Bridgewater State Hospital for the Criminally Insane in Massachusetts, earned him much acclaim, as well as several lawsuits. Ever since, Wiseman has trained his camera, and his critical gaze, on the workings and practices of American institutions. PBS has a long-standing agreement to broadcast each of his films as they come out.

Wiseman's newest film is a three-hour-plus study called "Domestic Violence," opening this week in New York. The 71-year-old filmmaker and his crew spent more than two months in and around Tampa, Fla., following the police as they responded to domestic violence calls, and spending time with residents of The Spring, a shelter for abused women. The result is an unblinking portrait, at once engrossing and difficult to watch. We see a woman, bloody and broken from a beating, being taken away in an ambulance. We hear a 5-year-old girl talk about her abusive father; she tells her counselor, "When my dad dies, I won't cry." At The Spring, women who are victims of violence gather to discuss their lives, and we are treated to story after story of cruelty and abuse. One counselor notes that there is "not a facet of the world unaffected" by violence in the home. Incredible figures corroborate this: One-third of all police time is devoted to domestic violence cases; one woman in three will be abused in her lifetime.

"Domestic Violence" is intelligent, and scarcely didactic. It offers no solutions, and it does not moralize; rather, it paints an unforgiving picture, in strokes broad and fine, of the violence men inflict on women. A follow-up film, "Domestic Violence II," now in post-production, will study the court system and look at the perpetrators of such violence. "Domestic Violence" is Frederick Wiseman's 32nd film, and it is as pure and as powerful as his first.

Wiseman spoke to Salon from Paris, where he is editing his second fiction feature.

In your career, you've addressed a vast range of issues and institutions. What gave you the idea to make a film about domestic violence?

It's a subject that's interested me for a long time, so when I found a situation where I could get permission to do the film, I jumped at the opportunity. Violence is a subject that has interested me in a lot of my other films -- "Titicut Follies," "Law and Order," "Juvenile Court," "Missile," "Maneuver," "Basic Training" and "Sinai Field Mission" all deal with aspects of violence. "Domestic Violence" is just a natural extension of some of the ideas and themes that I've been dealing with in these other films.

What did you know about domestic violence before you started the project?

Very little. I had a slight acquaintance with it from reading the newspaper accounts of various well-known cases. And many years ago, I taught family law, so I was familiar with some of the legal issues connected with domestic violence. But in no way would I suggest that I was an expert on the subject, or even very knowledgeable about it. Like the subjects of all these films, whatever knowledge I acquired, I acquired in the course of making the film.

The film takes place entirely in Tampa. Did you choose Tampa because it was a typical American city, or because it was in some way unusual?

I made the movie in Tampa because I got permission to make the movie in Tampa. And the community in Tampa seems to me to be extremely well organized to deal with domestic violence issues. There is a judge in the Hillsborough County Court, the chief judge there, who was interested in domestic violence, and he and other leaders of the community put together a coordinating group, which consists of judges, the sheriff's office, the police department, the D.A.'s office, legal aid, the shelter, children and family services.

All the various city and state and county organizations that deal with domestic violence work together, and as a result, my impression of Tampa is that there's been a great effort to educate the people in the community to recognize that it's not shameful to report incidents of domestic violence. Florida has a zero tolerance law, so that if there's any kind of physical abuse, an arrest has to be made. As a consequence, a lot more domestic violence cases get reported. It doesn't mean that there's more domestic violence, it just means that people feel somewhat more comfortable about reporting it, and less shameful about it.

Did you encounter any resistance to this project?

No, I didn't. I was very pleased that I didn't, obviously. The women in the shelter were extremely cooperative. Toward the end of the shooting I was talking about the film with a group of them. I had previously told them that the film would be shown theatrically and on public television and I asked them why they agreed to be in the movie. They said they cooperated because they wanted to let other people know about their experiences with the hope that it might be helpful to others in a similar situation. I thought this was extremely generous given the complexity and difficulty of their lives.

So, what's to be done about all this?

What's to be done? I'm no expert on that. I admire the patience and perseverance of the people working at the shelter. I thought that the staff, with their diligence and their patience, got through -- at least appeared to be getting through -- to some of the clients. It's hard to know the long-term effect. It seems to me they were people of good will who were committed to trying to help their clients understand the destructive patterns in their behavior, and to try to assist them to break the pattern. That's quite a lot, actually, because it requires grinding, day-to-day work. There's no kind of "shazam" or easy solution to the situations the clients were in.

I'm interested in the idea of documentary film having some social utility. Could you speak to that?

Well, it's very hard to know. It's very hard to measure. When I first started out, I had a rather naive and pretentious view that there was some kind of one-to-one connection between a film and social change. But now, while I like to think there might be a connection, I think there is no real way of knowing. People have all kinds of sources of different information, and it's totally presumptuous to assume that any documentary, or any one work of any sort, is going to be that important. Which is not to say I don't hope it has an effect, but I think if it does, it's elliptical, subterranean, circuitous and certainly not measurable.

Could you describe the process of making this film? How much footage did you shoot? How long did it take to edit?

The shooting was eight weeks, and in eight weeks I accumulated about 110 hours. The movie took about a year to edit. And the second one will also take about a year to edit. You make or break a movie like this in the editing. You can have good material and screw it up, and you can have mediocre material and improve it by the way you put it together.

I have no idea what the themes or the point of view are going to be until I get well into the editing. I don't have a story in mind in advance and I don't set out in these movies to prove a thesis. I discover what the themes are as I put the film together, as I edit the sequences and study the material.

So it's only after maybe six or seven months of editing, when I've edited all the scenes that I think might make it into the final film, that I actually start working on a structure. And then it takes me a couple of days to do the first assembly of the film. The first version of the film comes out to be 20 or 30 minutes longer than the final version. And then what I do is work on the internal rhythm of the sequences, and then, particularly, on the rhythm between the sequences. I work very hard to find a dramatic structure for the material. They're meant to be movies, and so they have to work as movies, whatever that may mean. Timing and rhythm are extremely important.

Could you talk about your editing style? A lot of movies and television shows today use lots of fast cuts. You seem to be in a different camp.

I think I have an obligation, to the people who have consented to be in the film, to make a film that is fair to their experience. The editing of my films is a long and selective process. I do feel that when I cut a sequence, I have an obligation to the people who are in it, to cut it so that it fairly represents what I felt was going on at the time, in the original event. I don't try and cut it to meet the standards of a producer or a network or a television show.

My principal obligation is to make as good a movie as I can, and try to fairly represent the complexity of what went on. That means that sometimes the films are long, it means that sometimes the scenes are long. I don't think it's fair just to cut to the most sensational part of the scene, and then cut to another sensational scene, because that means that there's absolutely no context. In each scene, I have an obligation to provide the context and, from my point of view, the result is more dramatic than when you just cut to the most sensational aspect. The so-called juicy part of the scene is more comprehensible and more powerful because the context is clear.

When you're working on a film, do you consider your audience?

When I'm making a movie, I have no idea how to think about an audience. I think the kinds of surveys they do in Hollywood are basically high comedy. I hope you don't think that what I'm about to say is arrogant. I have no idea how anybody else is going to respond to the movie, what their experience or their interests are, what books they've read or movies they've seen, what their general interests are, etc. So the only audience I have in mind when I make the movie is myself. And I try to make it to my own standards, and I hope that somebody else who sees it will connect to it. The only things I know a little bit about -- and I don't say I know a lot about them either -- are my own standards.

Shares