One of the advantages of geezerhood besides getting up four times a night and forgetting our children's married names (and even our children's names) is that you often can get your way, even when you shouldn't. I had a chance to experience this when I went to Mexico this fall.

My friend Jesús and I drove for a day across the upper part of Mexico from Tijuana to the end of the free zone and the jumping-off point of Sonoita. However, when we went to pick up the papers for my car (which would enable me to legally make the long drive south to my home in Oaxaca), I was told that since I didn't surrender the car papers when I returned last year, I am technically still in Mexico, illegally.

My truck and I are right there in front of them to prove that I have indeed returned, but the great logic of all bureaucracy of all times is that if you didn't do it right, you didn't do it at all.

I am told thus that they will not issue me a new visa. It's 8 p.m. The temperature has dropped to subfreezing. The office of appeal that they direct me to has no heat and is all government --- dull fluorescent lights, dirty walls, stacks of papers everywhere. The man at the front desk, a Mr. Toad, demands to know what I want. I have never seen a grown man who looks more like a bufadora, warts and all. Even to the hands, set on the desk, palms down, fingers turned inward. He's squatting there, and I'm his fly.

I explain to Toad Man that I have been going to Mexico for 15 years and it is ridiculous that they will not give me a visa. I tell him I want to see whoever is in charge. He says that's impossible, that La Abogada de la Frontera, the chief, is very busy. I say I have to see her just for 30 seconds. He says it cannot be done. I say I'll wait.

I have Jesús put my wheelchair right next to El Bufadoro's desk, so that I'm in his line of vision. Then, with no prompting, after five minutes, I begin to shake. Northern Mexico desert country can be very cold, and I am, after all, a nervous old guy with the heebie-jeebies in a wheelchair in an unheated government office. In the words of the old Appalachian folk song as collected by John Jacob Niles, I begin to shake, rattle and roll.

My wheelchair is an antique (Quickie II --- like a 1953 Bentley). It has loose wheels and mysterious chains and hanging things, so, under normal operation, there's always clanking and banging. In the cold, it is redoubled. And while my wheelchair cranks up with the "Anvil Chorus," my teeth decide to join in. Also my arms --- this one's new to me --- go into attacks of palsy. It gets quite noisy in that normally quiet office.

I say nothing to Mr. Toad, don't even look at him, just sit there and jingle my bells. There might even be a splotch or two of saliva that escapes my purple lips (I am no longer in control, right?). After an hour of this, the Toad gives Jesús a tight smile and tells him that La Abogada is still busy. But I sense, through all the racket, that something has changed.

I have proved my stoicism, my willingness to sit -- neither cool, calm nor collected, but at least a presence, perhaps an artistic statement out of Laurie Anderson: "Persistent Old Fart with St. Vitus' dance."

A signal is passed somewhere. The Abogada's pretty assistant comes and asks me what I want. "Si mira Vd. mis documentos ... " I hand her my papers and give her my well-rehearsed 30-second explanation of why I've been terribly wronged.

In 10 minutes she is back, tells us to go on down the ramp, that they will give us our papers. I thank her profusely, smile at the sullen Mr. Toad -- thank him too -- and we are off in a flash.

I live half the year south of the border, and it is written, despite NAFTA and all good sense, that certain animals, along with drugs and guns, are not to be admitted into Mexico. Some animals are OK. For instance, they let in Americans by the millions, those who have nothing better to do than drink themselves silly on $6-a-gallon mescal beginning at the breakfast hour, ending at midnight or so, lurching about the bars, cursing Mexicans and looking for a good fight.

These -- along with dogs, cats and, possibly, Gila monsters -- are acceptable. But feathered creatures, no. This includes chickens, ducks and, presumably, ostriches and moas. I suppose the rationale is that the Mexican government wants to prevent the spread of certain avian diseases, like dropsy, henbane fever, chicken pox and cockamamie.

For those of us who are chicken or duck lovers, this amounts to discriminatory treatment. Why should a poodle with pink ribbons be given preferential treatment over a Cochin, a White Crested Black Polish or a Pekin?

Fortunately for those of us who have this feathery love that dare not speak its name, our pets come in two forms: born and unborn. If you can't import the full motley, there are always a dozen or so hard-shelled fetuses, delivered fresh from the womb, ready to be scrambled, fried ... or hatched.

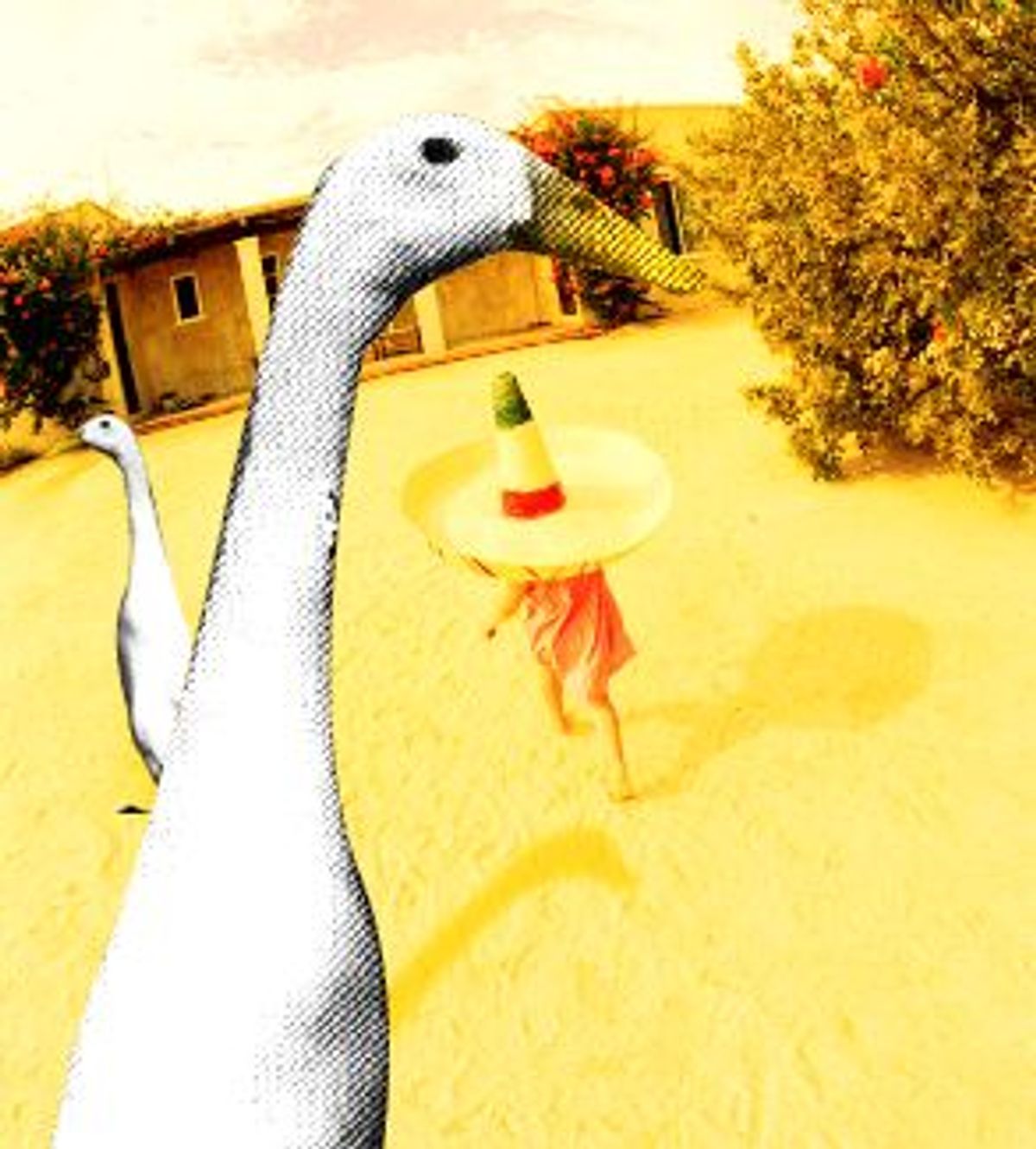

This year I've come to be interested in the rarest of the rare of ducks. They are called Indian Runners, and they'll knock your socks off. Runners do that all the time -- that is, they run about, willy-nilly. Also, unlike your regular duck, which is hung fairly close to the ground, the runner stands upright, like a penguin. If it weren't for their wings and coloration, it would be like having a flock of Emperors in your backyard.

Last year, I shipped 20 black Indian Runner eggs down to my winter shack in Southern Mexico, along with an incubator. When they arrived, Jesús popped them in the incubator, and exactly 28 days later, 12 of them were, as they say in Spanish, "dierón a luz" -- given to the light. Three of them succumbed to what I believe was excessive quackery. The other nine have grown at an alarming rate, and now stand 6 foot 3.

I exaggerate a bit, but given their noise and blind, down-home stupidity and their need to run about -- should I say it? -- like chickens with their heads cut off, they fill a space as big as all outdoors. They measure about 30 inches from stem to stern.

I left these noisy freaks in the hands of Jesús and he cared for them next to his outhouse until I returned this fall. There they were -- nine black beauties -- waiting for me. With only one problem.

Puerto Perdido is forever short of water, and so Jesús had not been able to give them a swimming area. Thus when I arrived, my ducklets did not recognize the tub of water we set out for them. They thought it was something dangerous and moved to the far side of their cage, eyeing it warily. I immediately instituted daily YMCA swim classes for our charges.

You would think it easy to teach a duck how to tread water, right? No dice. They are as receptive as your mother was to your first sweetie. And these quackers have immense wing power, somewhere around, it's been estimated, 25,000 foot-pounds per square inch of lift.

They struggle when we pick them up, scream when we put them in the tub of water. They fly out of it as fast as they can, sopping us -- their loyal instructors -- and then skulking about on the far side of the cage, muttering like American teenagers after you've invited them to do a little yardwork. In other words, they were not overly fond of our Esther Williams Beauty Swim Course.

But I am patient, and loving -- and we are still far from the Hatchet Solution (duck à l'orange) for our landlocked Indian Runners. I hope to report to you shortly that they have accepted their lap pool -- that they have come to know and love what is, after all, their true nature: that they have taken to it like a duck to water.

You'd probably like No Name. She has eyes bigger than my own, skin of fine mahogany, a nose they used to call "button" and a mouth given to much smiling and little crying. She's exactly a year old, and she was offered to me yesterday; if I want another daughter, she's mine.

Her mother is María. María's poor, pretty and now pregnant with child No. 2. She "likes the men," says my worker Jesús. We don't know who the father is and the child has no name because her mother hasn't gotten around to it. Thus, "Sin Nombre."

I thought about that one for a while: being a father again. The last time I did it was over 40 years ago. I'm not sure if I am up to it. There's a certain, well, running about to be done -- responsibility, caring, love. It's something we might do if we were 35, or even 50 again. But no matter how fetching the young lady, no matter how well behaved, I don't think I can pull it off at this late date.

She scarcely cries -- "No Name" is not given to tears. She does know how to hug, however. She took quite naturally to my holding her, laid an affectionate hand on my arm, head on my chest. They are quite warm at that age, sweet-smelling.

Is it immoral, this offering up of one's own flesh and blood to a stranger -- albeit a stranger who's a gringo, and, presumably, will have the wherewithal to care and feed for her? Who's to say? She was born at a time when her mother was 17, ill-prepared for diapers and the messy world of child care.

Her mother is smitten with the men. Among the caravan, No Name's father is an unknown. He was one of a series who came through the hutch, spent a night or two, moved on. It was only after a year of motherhood that María let it be known to her family (which includes the wife of my worker Jesús) that the child was available for the taking.

Up north, public service agencies would become involved to keep the family -- what little there is of it -- together. A social worker would be called in to deal with the violence (the mother has a tendency to slap her unwanted daughter around, I am told). There might be a foster family found who would be paid on a per diem basis, willing to take her on for the cash flow, if for nothing else. In any event, it would have been handled differently -- not this general call put out to all comers, with the need of a quiet girl-child, of winning ways, who is, now, of so little interest to her mother.

I asked Jesús and his wife, Maruga, if they could take No Name. "Creo que no," he said. They already have two boys, one 6, the other 4. Jesús and Maruga grew up in families where there were many hungry mouths and little food -- sometimes, for days at a time, nothing in the house to eat but tortillas and salt. There was not much in the way of help from the fathers (Jesús' father disappeared; hers was an alcoholic). Both had to drop out of school early on to support a dozen or so brothers and sisters.

They have vowed that their two boys will do better: Felipe of the shy smile, Rogelio -- who, full of 4-year-old wisdom, will talk your ear off if you give him half a chance. Telling me, for example, the important news of the day: He and his mother went to the public market; she bought him an apple; he wanted a balloon; she told him he'd have to wait for Los Reyes -- the Day of the Three Wise Men -- he told her he didn't want to wait and so on.

Jesús and Maruga want their two boys to escape the world they grew up in. They want them to have more than one set of shirts and shorts, shoes that aren't falling apart, a doctor to look after them when they get sick. They want the two to go to school and to stay there. Two boys -- for now, that's enough. Thus they rejected her cousin's offer. She then asked Maruga if she would ask me.

"Sin Nombre." No name. A tiny human life. Offered up just like that. This is no book or television "novela." This is the real thing. Her fingers clutch around my index. She looks at me, looks into the heart of me. Will you be my father? Ah, those eyes. Stop looking at me, will you?

A child with, perhaps, no future, unless I choose to give her one. A child I could raise as if she were my own. Or, maybe, just to be the affectionate uncle: to be sure that she has all she needs, to protect her from the anger of a frustrated mother. A mother who, after all, just wants to get out of the house, to be with the boyfriends she fancies more than setting up housekeeping for her daughter, and the second on the way.

A sweet child. For the taking. If I want.

Shares