By now, the oppression of the Tibetan people, their culture and their religion by the Chinese government is a proven and accepted fact. Since 1950, when the Chinese invaded sovereign Tibet, the circumstances of the deaths of hundreds of thousands of people have been chronicled in print and film many times over, as have the destruction of Tibetan Buddhist monasteries, priceless art and the livelihoods of many more thousands who have had to flee that country.

One aspect of the situation that has been less chronicled is the migration of thousands of Tibetan children every year, very often without their parents, over the Himalayan Mountains to Nepal and India. Usually they go in groups, led by mercenary Tibetan guides who are paid for their efforts by the families of these children, who wish better lives for them than can be found in Tibet. Many thousands of children have reached the Dalai Lama's Tibetan capital-in-exile in Dharamsala, India. Some have not. The routes are dangerous and on occasion deadly, simply by virtue of the weather and terrain. The children can attempt escape by less arduous routes as well, although these routes are frequented by Chinese police and army, Nepalese bandits and other brigands who may attack, imprison or rob the children.

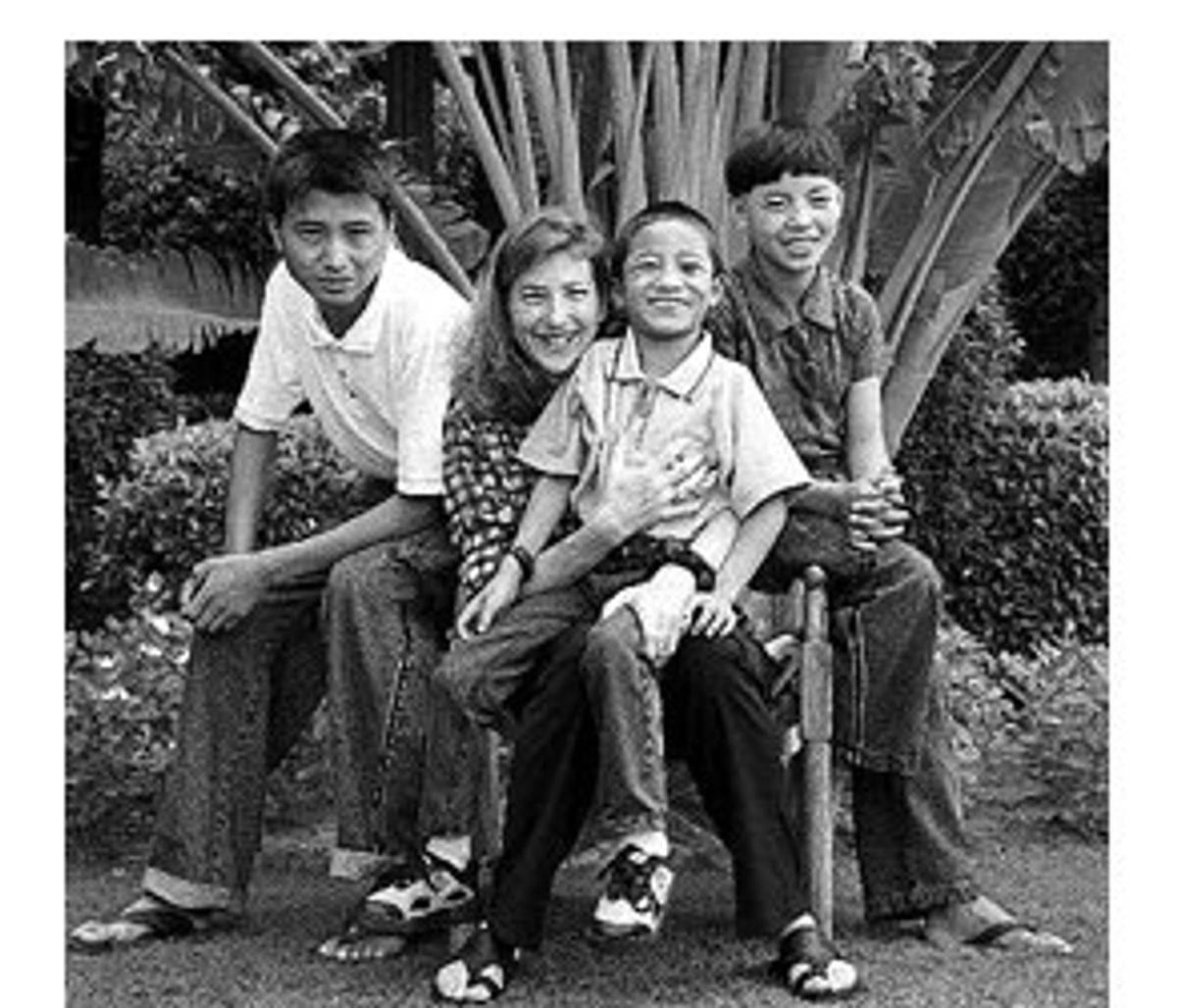

New York photographer Nancy Jo Johnson helped three young Tibetans leave the country in 1996. Her harrowing effort was chronicled the following year in a LIFE magazine article, accompanied by her photographs. She first encountered Tibetan refugees in the early 1980s while living in Katmandu, Nepal, and has been involved in the Tibetan issue ever since. She is a member of the board of directors of the United States Tibet Committee.

Johnson has been working to raise awareness about Tibetans through her photography for over 15 years. A recent exhibit of her work, "Tibet: Survival of the Spirit," held at the Canon Rotunda of the U.S. House of Representatives, was sponsored by Rep. Tom Lantos, D-Calif., and former Rep. John Edward Porter, R-Ill., co-chairman and honorary co-chairman, respectively, of the Congressional Human Rights Caucus. It commemorated the 40th anniversary of the Dalai Lama's March 1959 flight to exile in India. In a recent conversation, Johnson talked with Salon about Tibet past and present.

The story of the children that you brought out of Tibet is a kind of mini-novel in the Graham Greene mold, of a Westerner risking her life for three Tibetan children who, until shortly before the story begins, she had not even known. This was an extraordinarily dangerous thing to do. Where are the children now?

There are three of them: Tsering Norden, a boy, who is 9; Lhakpa Dolma, a girl who is 13; and Tsering Dorje, another boy who's now 17. They're living in northern India at one of the Dalai Lama's compounds that is called a Tibetan Children's Village. There are many of these villages, and they'll contain schools, medical facilities and so on. So the children are getting an education in Tibetan, English and Hindi. The purpose of these villages is to ensure that the children maintain their Tibetan identity. The environment is entirely Tibetan, or as much so as possible without actually being in Tibet itself.

I plan to sponsor the higher-education studies of the children I brought out here in the U.S.

Does the Tibet -- or more specifically, the capital city Lhasa -- that existed in 1950, or even as recently as 10 years ago, still exist?

The fact is that the cultural and religious landscape of Tibet has lost its traditional basis, by now almost entirely. But there are many people who continue to believe that their children will be able to better maintain themselves as Tibetans elsewhere -- in India or elsewhere. They worry that, if their children stay in Tibet, they will not have even the opportunity to know their Tibetan identity.

But this wish for escape is not universal among Tibetans?

No, not any longer.

What's happened to change that?

It's important to know that, from the 1950 Chinese invasion up to about 1989, 90 percent of the Chinese presence in Tibet was military personnel. Before 1989, the uprooting of the Tibetan culture had not really happened in the way that it has happened since 1989. So when I went there the first time in 1987 and observed the military occupation, the place still felt like Tibet in every way that we think about it: historically, culturally ... in the way that we've read about it. Even though most of the monasteries were destroyed in the occupation and during the Cultural Revolution, those few that did remain cultivated a religious activity that was more pure in the traditional sense than what is taking place there today.

Starting in 1989, the Chinese government developed a policy of population transfer, to move Han Chinese citizens from Mainland China into Tibet. They offered bonuses, financial and otherwise. Basically, they helped them get set up there. By 1995, everything in Lhasa had begun to have the Chinese look and feel, from the bottom up -- store fronts, schools, whole neighborhoods. And there were profound cultural upheavals as well. The curriculum in schools, for instance, which was taught almost entirely in the Chinese language. I visited a couple of schools in Lhasa that Tibetan kids go to. They get instruction in the Tibetan language. But it's simply a class that is part of the larger curriculum.

So, you've had a generation of Tibetan children caught in this change that are now in their 20s, who've either been raised in these Chinese language schools inside Tibet or who were shipped off to mainland China to school and have since returned. They're speaking fluent Chinese, and have been brought up under the Chinese political system and its propaganda. So they've actually changed. They don't present the same portrayal of religion, spirit and energy that had fascinated so many of us on the outside when we had first encountered the Tibetan people some years ago.

I personally went from the experience of Lhasa years ago as a place that had a kind of underlying tension everywhere you went, where the religion was alive, where there was a fierce defense of it against very stiff odds, to a place that now suffers a clear sense of resignation. I felt this very strongly during my last two trips.

There's a point where you fight the system or you join it. People are making money now in Lhasa. You see cellphones. SUVs. Theme parks for children! Children dressed in frilly and colorful imported clothing.

Are the Tibetans themselves allowed to buy into this new Tibet?

Yes. Absolutely. For example, the woman who helped me obtain all the permits I needed during my last trip -- which would be a very tough thing for me to do alone, dealing with the Chinese government as an outsider -- was a 30-year-old Tibetan woman who had started a travel business, speaks fluent Chinese, regularly shops in Hong Kong, whose parents still speak only Tibetan. She's not interested in the Tibetan traditions at all. She never goes to a monastery. She's not religious. She's an entrepreneur, and a very successful one. She goes to a Lhasa health spa in the evenings, where the better-to-do Chinese prostitutes go to work out. There are other wealthy Chinese women there, wealthy Tibetan women. She invited me to go there one evening for a massage. So I went. I was very curious.

What language were the Tibetan women speaking at the health club?

Chinese! So you wonder, are these women speaking Chinese to their children? And the answer is, yes.

What happened spiritually is that the Chinese government went into the monasteries and imposed a re-education process upon them, in which they made it illegal to worship the Dalai Lama. Anyone who had a picture of His Holiness had to get rid of it. Imagine having to burn the very representation of your heart's center! When that process began, we saw a huge escape from Tibet of young monks and nuns who had been trying to hold out under the Chinese influence. This was very recently -- 1998, 1999.

But then the Chinese government realized how forceful the Tibetans outside of Tibet really are. So now they've changed that policy. Now they say, "OK, you sent your monks and your kids out of Tibet. You get them back right now, or you guys will go to prison." They now realize that maybe those kids and those monks that went to Dharamsala are not ever coming back. Maybe they're going to join the Free Tibet movement (what the Chinese call the "Splittist Movement"), and maybe now they're going to have a voice! So the Tibetan parents that are left in Tibet don't know whether, or how much, they can trust the Chinese, because the Chinese change their tune so often and so violently.

Also, when you land in Lhasa and encounter the Chinese who work at the airport, you know that you're in a police state. It's clear. People don't smile. And when you consider the traditional Tibetan culture, in which people did nothing but smile for thousands of years, and then consider what's happening now, with this new Tibetan consciousness (like that of my woman friend at the health club who is so driven to succeed) you realize the level of confusion that exists for the Tibetan people now. You realize, seeing what has happened, that maybe the parents of these young Tibetans who did not leave the country saw that their children, in order to survive, had to buy in to the Chinese model. Those parents didn't cop out. They didn't have any choice, if they wished for their children to survive.

What is the instance now of Tibetan young people going to university in China?

Much higher. The Chinese took a lot of Tibetan students, even at the high school level, out of Tibet and into China, where they gave them an extensive education. Those students are now back in Tibet, a part of this "successful" Lhasa business community. I've worked with them.

This Chinese higher university education scheme for the Tibetans is even more pronounced now. It's almost as if the opportunities for education are attractive to anybody, whether it's Chinese education or not. And the Dalai Lama himself will say the same thing. I paraphrase him: "OK, we had this large percentage of our population that was not educated. At least now they're getting an education, even though it's totally directed by the Chinese. It's better than no education at all."

I have met a lot of those kids, educated in India, who have gone back to Tibet. And what happens is that they no longer have access to books, other than what's available in the Chinese-controlled situation. The kind of freedom of creative thinking ... whatever they worked so hard to develop in exile, it just gets squashed when they get back to Tibet. They become very lazy. They get really depressed. They go to the discos that are offered to them now, and they just seem to exist. This is tremendously sad.

Presumably they're not speaking Chinese when they come back.

They have to learn Chinese in order to get work. There has to be communication on that level as well as in English. A lot of the older kids who have come out do speak Chinese already. In fact, my older boy, Tsering Dorje, has just taken his vacation from school to travel to Nepal and work on his computer skills and his Chinese language skills. He speaks Chinese, and I've made a point of having him continue that Chinese language instruction because he will need it if he ever decides to go back to Tibet.

Are they teaching Chinese in Dharamsala?

Privately, some do. Some of the schools are trying to get it into the curriculum, as an elective for those older escaped kids who want to keep up their fluency in Chinese.

There's a certain irony in that, of course.

Of course!

What I understand to be the case is this: There is a continuing resistance effort in Tibet. There are still freedom fighters. People are still trying to get out. But as the economic situation improves there for the Tibetans themselves, and as they begin to be immersed within the Chinese society -- economically, linguistically, etc. -- the opposition to the government and the need to flee seem to be less. And the Tibetan consciousness, that was so famous and so much in the foreground 15 years ago, is slowly being reduced and reduced and reduced.

I think so. But, I must say that that is completely and totally my own opinion. No one wants to hear it, I will tell you that. But I think it is the truth. So ... now there is this new, young class of Chinese nouveaux riches in Lhasa. They bring their children to an amusement park that the government recently built. And the upwardly mobile young Tibetan parents bring their children there, too. They're all mixing together at the amusement park. You see people renting these little go-carts for their kids. Go-carts in the form of Chinese tanks or Chinese dragons. Two or three of the families will be Chinese; one or two will be Tibetan. They're all getting into these weird little decorated carts, and the whole thing is so surreal!

It's surreal because this park is located on a big open square right below the front of the Potala, the Dalai Lama's old monastery-palace, an ancient monument and a place sacred to Tibetan Buddhism. It is almost too much to bear. It is so painful that, well, you just can't think about it too much. On my last visit there, I vowed to try to look at such things in the new Tibet objectively, which, with my history in Tibet, is almost impossible to do. To really see that these young Tibetans are now living in a society in which their children are eating well, they're going to school ... They're not unhappy! They may not be happy in the way that they were, but it's a changed world.

The most tragic part of it, though, is the loss of the spiritual element. Somehow with Tibetan culture and the Tibetan Buddhist Dharma, there was a practice that was really true in the lay people. The whole spiritual community was supported and embraced by the lay people in a way that wasn't just an activity. It was a way of life. There was a characteristic of inner beauty that always came to the surface. Famously so. And I think it is that that they're losing. I think it's maybe what they have already lost.

Shares