What was that doing here?

He was scarcely even a puppy, a tiny black bit of fur the size of my own small hand, just able to walk across the beach. I scooped him up and turned around, looking for his owner. There was no one behind me, just the beach restaurant where my lunch had been cooked. It had been simple grilled fish with rice and a few tomato slices. The restaurant offered salt but no pepper or hot sauce -- expensive luxuries here.

Twenty feet in front of me, close to the turquoise sea, a group of Italian men with Cuban girls laughed and bantered. The men were 40-ish but fending off gravity better than most American males, and they didn't look bad in their bathing trunks. The women were spectacular in their tangas, not an ounce of fat on their 20-year-old bodies. They were ebony. There was an adage around that you heard once you'd been in Cuba a few times, that the Italian men always went for the really black Cubanas. What interested me about this was that in Italy, bourgeois Northern Italians will sneer at Sicily or even Naples as "Africa."

The puppy was completely black and would have been beautiful, but for the way every inch of his skin was covered with fleas or flea bites. Using the big bottle of water I'd brought to the beach, I began to clean him and scrape away the fleas. He squeaked in discomfort as I cleaned him, but he was so little that his resistance was no impediment.

By this time other beachgoers were coming round to watch the drama. The Cuban girls ignored the puppy, but the foreign men were concerned. An Italian man thought he'd seen a black bitch with milk-full teats nearby. But when he found her -- X-ray thin, mangy, unhappy -- and led her over, she turned her back on the puppy. The puppy followed her. He grabbed helplessly for her teats as she backed away.

A Spanish man volunteered that the perrito -- the puppy -- was probably under a week old and needed milk. At the restaurant they regretted they had none. I had forgotten that in Cuba milk is rationed, and only government-sanctioned restaurants and families with children may obtain it at local peso prices. Everyone else has to pay in dollars, at prices approximating American supermarket prices. This puts it out of the reach of most Cubans, whose official state salary is about $10 a month.

The Spaniard left to go buy milk from the dollar store a hundred yards away, refusing my offer of payment. He returned with one of those European brick containers. When we opened it and poured some milk into a bottle cap, it was ochre. Probably old, no expiration date. Luckily I was feeding a dog, not a baby. The perrito gladly drank four bottle caps' worth. I'd have to give him a bath in the sink back at the hotel in Havana, I decided. And then I'd have to try to find a family to adopt him.

On my fourth visit to Cuba, I knew enough to realize that this would not be an easy task. Most families could hardly afford to feed their kids, much less a pet. This was why the lovely girls on the beach were sleeping with the foreign men old enough to be their daddies. And while well-off Cubans did have dogs, as often as not they were an element of conspicuous consumption and had to be recognizable breeds. This puppy was a mutt -- he wouldn't increase anyone's status.

That evening, with the perrito asleep in my hotel room, I found myself at El Rio, or Johnny's, a Havana nightclub that exists for one reason. Very short brown girls were trying to attract the attention of substantially built white men, mainly, judging from the looks of them, Northern Europeans. Perhaps twice as many women as men were in the bar, and some of the girls danced with each other. They were animated but self-conscious. There was no joy here; it was a place of business, though the decor was delirious and the flashing strobe lights made the cushiony metallic walls even odder.

My friends Beth and Lucy and I were here because two German men we had met over dinner invited us, but it wasn't clear why they would want us around to watch the scene unfold.

The girls, I knew from previous visits to Cuba, were not only college age, but actual college students. They were not quite part-time prostitutes, but something like prostitution was going on. "They're happy if you buy them a good dinner and a pair of shoes," one Italian man had told me.

The girls were so short -- at 5-foot-6 I was a head taller -- because of malnutrition during the so-called Special Period in the early '90s when they were growing up. When the Soviet Union stopped supporting Cuba and then suddenly collapsed, food had become scarce in this one-time agricultural nation. Even middle-class urban Cubans found themselves short of food. Judging by their skin tone, these girls were not middle-class.

Even five decades after the Revolution, color lines largely equal economic lines in Cuba. Though the gross inequities of pre-Revolutionary days had been eliminated, blacks clearly occupied a lower economic rung. I'd never seen a casa particular, or pension, run by a black family, or a paladar, an informal restaurant, with black owners. I'd never seen a black driver of an official cab. These were three of the best legal ways to acquire foreign currency in Cuba and blacks didn't seem to have access to them. (The houses people had at the time of the Revolution were largely the houses they had now, which is why white people were the owners of the big places that made good pensions.)

Blacks could play music, of course, just as they could in the Jim Crow South, and some of Cuba's economic elite are successful salseras who make money overseas. But the most obviously black occupation is not singing and dancing. The hardcore whores, the jinateras, are almost all very dark-skinned.

"Hello, I am Aracelys." A brown girl with smooth black hair looked up at me with a sweet face and the social ease of a debutante. I shook her hand, glad that we would be able to talk in English. My Spanish is weak.

"Are you a friend of Hans?" she asked. He was one of the Germans.

"I just met him tonight", I answered, then amplified, "Solo esta noche. Somos in un palador insieme."

Her face lit up. "So you no ... " and here she wiggled her hips, "... with Hans?" The debutante aura collapsed abruptly.

"No, no," I replied with genuine shock. "Solo un amiga nueva. Mio novio es in Nueva York," I lied. The notion of a liaison with the pallid whore master appalled me.

"Hans very good man," Aracelys observed.

"Si, claro," I allowed.

Aracelys began to tell me of her refrigeration technology studies, but just then Hans joined us, sweeping her up in a bear hug. She clung to him and whispered something in his ear. He whispered back, then she moved away, clearly disappointed. Soon she was dancing with another girl, obviously trolling for a man.

"Are you enjoying yourself?" Hans asked.

"Yes, but I'm tired. I was at the beach today. I think we'll be taking off soon."

I am rarely tired. I was angry. Did these men ever wonder whether the little Cuban girls were enjoying themselves? Whether the sex was good for them, too?

I have led an adventuresome life with a lot of casual sex. Mainly it has been pretty good, even very good. When you make impulsive decisions to go to bed with someone you usually at least pick someone you have chemistry with, if not someone whose character you will come to admire. But sometimes it wasn't good and I had to get out of it, hopefully without destroying the man's ego.

What would it be like to have to continue to have sex with one of those men, if I wanted to eat? What if I were getting $5,000 a night to fuck him? Wasn't that about what $50 translated into here? Could I learn to like the bad sex, or at least persuade him that I did? Why had Castro beggared his nation and put a generation of young women in the position of learning to be whores? Did the daughters of the Cuban leadership have to wiggle their butts in nightclubs? What color were those girls?

In the cab back to the hotel, Beth, who like me is old enough to feel protective of the Johnny's girls, blurts out, "I would like to pay those girls $50 not to go home with those men!"

Beth and I are both staying at the Hotel Nacional ($110, or ten months' wages for the average Cuban, or the price of three girls from El Rio). It's a deal; the place would cost three times as much anywhere else in the Caribbean.

There is an argument to be made that this is politically incorrect, because the money goes to the Cuban government. If you stay at a casa particular, a private house, as I have sometimes done, the money, less some taxes, goes to the family that runs it. You can bring Cubans there to have sex. They can't go above the lobby at the hotels. And the private houses are cheaper. Lucy, a part-time editor on a budget, is staying at a nice one for only $25 a night.

But the Nacional is very beautiful, with a lawn that runs down to a view of the harbor, and there are two pools where I can swim laps and a tennis court where Beth and I can play for $4 an hour. Besides, I had traveled in China and stayed at government-run or -sanctioned hotels without concerning myself with the politics of the situation.

When I enter my room, Perrito is curled up in a ball on top of my beach tote bag. He is the size of a large sandwich. Fleas still hop on his back, but fewer. Perhaps I should bathe him again tomorrow. I force a little of the yellow milk down his throat. He doesn't seem to be able to sip from the saucer yet. He's so helpless, so adorable. I contemplate bringing him back to the States.

When I call the American Interests Section the next morning a nice Cuban woman says she thinks I would have to put Perrito in quarantine if I take him back to the States. That would be a death sentence to so young a puppy.

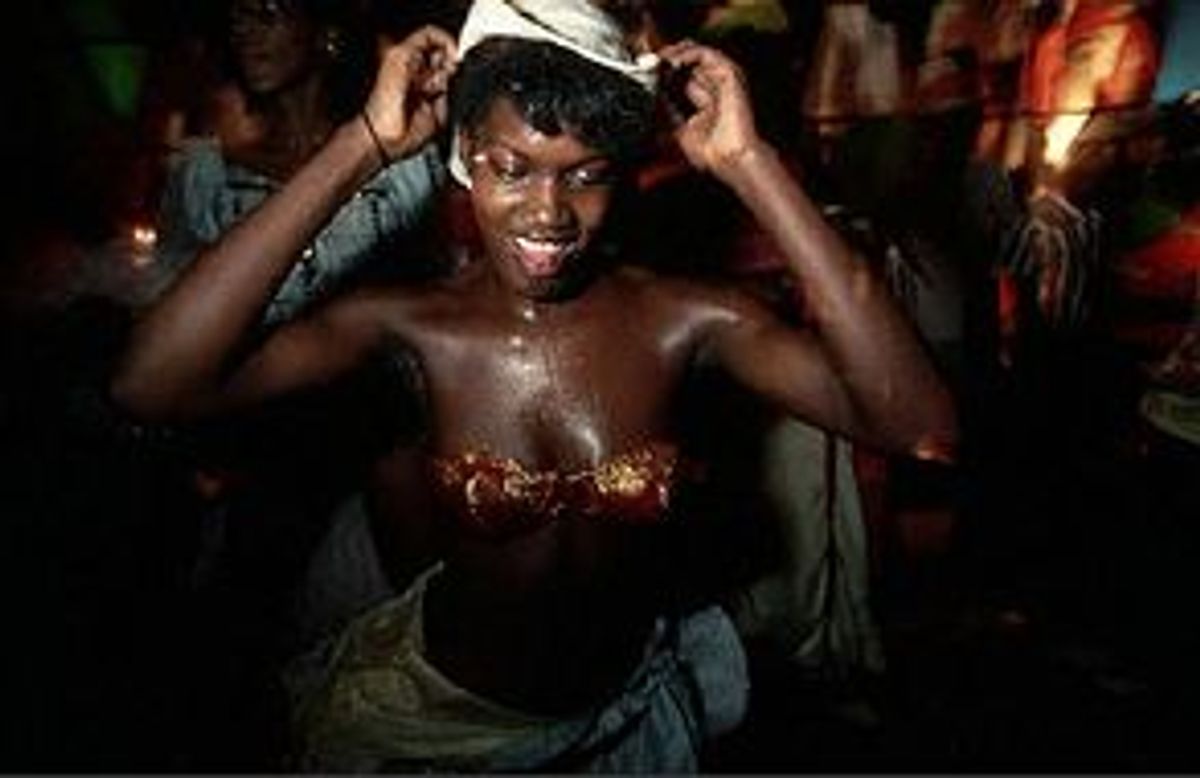

The next evening I go with my friend Tom to another nightclub, Palermo, in Havana's Chinatown. This part of town, just a couple of hundred yards from the central shopping district and a few of the nicer hotels, has a forlorn, ragged feel that reminds me of Mexico City. Maybe I have just traveled too much, for the circular bar also reminds me of somewhere else, the East Village's Vazac's. Like El Rio, this is filled with many girls and few men, the opposite of the usual American joint. It's a rougher place than El Rio, and accordingly the women are darker.

"Every girl here is for sale," Tom told me. "At one time, before I was married, I could say I'd sampled a fair percentage of the regulars. One night I did two doubles and one single; I think that was my record. You take them across the street, rent a room for $30, fuck them all night."

"Do you miss it, now that you're married?" In Cuba on business, Tom was being good, this trip.

"My wife and I fuck all night; we have a great relationship." That was more than I wanted to know, and Tom, sensing my discomfort, went on:

"One night I went to the room of this girl who, well, maybe was 16. I felt bad about it, but that added to the thrill, of course."

What were men like Tom thinking when they told me these stories? Now every time I saw him and his wife at a party, I'd be picturing him -- 40-ish, short, balding -- humping an exquisite little 16-year-old mulatta.

A tall brown girl, well dressed by local standards, with the narrow body and small features of a model, put her arm on Tom's shoulder and invited him to dance. I had to stop myself from glaring at her -- Tom had been in the middle of a sentence. He was soon back. "I explained that I'm with you, that I'm just here for the music tonight," he said.

"Not that you were married?"

"No."

The girl soon shimmied her way toward us again. She fingered the cashmere and silk shawl lightly draped on my shoulder, then pulled it away from me and onto her shoulders. I had a strong urge to punch her hard in the solar plexus. I pictured her crumpling forward, then falling down.

Immediately I felt ashamed. Let the poor girl wear the shawl for a minute. It had cost me a price equal to the fucking of many Cuban girls -- when would she ever have one of her own? She returned it as silently as she took it, after an interval of a minute or two. A Carmen, in her insolence and daring. What did she have to lose? Did her customers use condoms? Had she saved any of the money she had made? Was she supporting a family in the provinces, a child in an apartment nearby?

"Let's go," Tom said. "Los Van Van are going on in about a half-hour at Palacio. This place isn't happening tonight. By the way, you better get rid of that dog of yours. It's giving Lucy and Beth fleas, you know."

We walk out of the club with many eyes following us and I decide this is what it must feel like to be a movie star, except that I feel guilty in a way I don't think I would feel if I were a movie star.

The next afternoon I wait in the courtyard of the Hotel Nacional for my Spanish lesson to begin, and I think about the night at the Palermo. It reminds me of the time I went with a bunch of friends to a strip club in Mexico City that had become an obligatory stop for both local and visiting foreign artists for its perfunctory, sad sex show. The girls on the stage were dwarfish and ill-favored. They looked strongly Indian. Another American, the only black among us, explained to me that all the Mexican artists with us were from rich families, who bought them apartments and cars. They did not have to work.

I knew I would not have gone to a similar place in my own country, because Americans are not allowed to condescend to other Americans anymore. My night at the Palermo felt like the frolics of white people in Harlem in 1920. But why did I choose to feel righteous now? Months of my youth were spent in poor countries. I had visited many: Anguilla, Burma, Cambodia, China, Egypt, India, Indonesia, Jordan, Mali, Morocco, Nepal, Senegal, Tanzania, Tunisia, Turkey, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Vietnam, Zanzibar. I had been happy on those trips.

What is it about these poor countries? What savor do they offer us that Europe does not? Is it just the perfume of misery that makes us appreciate our own lives, frustrating as they may be? Was I happier in these countries when I myself was relatively poor for an American? I used to take $2,000 and go halfway across the world for a few months. That money might have been the income of 10 villagers in the country I visited, but it was also the savings of a year's work for me. Now things were different. I was comfortably off by American standards but the villagers were not.

My everyday behavior could not help but be inflected with unintended cruelty. When I invited my Spanish teacher to have coffee with me in the courtyard for our first lesson, it only struck me after I had ordered our coffees that there was something insulting about what I had done.

It was in the contrast between the two economies: I paid her $5 an hour for the lessons; she had initially asked for $2. That was the price of a cafe con leche at the hotel. Five an hour was great money for her -- half a month's official salary -- but it was two coffees for me. After that time, we still had lessons in the courtyard, but without coffee, which I found too embarrassing to order. And of course this was more her loss than mine. Sometimes I brought us chocolates from my room.

In New York I am a libertarian, a die-hard capitalist. In Cuba, I wish for capitalism for the Cubans also. But what to do now, sitting in the Hotel Nacional? The problem is with the luck of nations, the luck of birth into one place or another. I am starting to have a problem with my trips to the developing -- or, in the case of Cuba, the undeveloping -- world, a problem with the perfume of misery, with the way sadism is imposed by the luck of nations.

Cuba is more interesting than St. Barts, but perhaps I should go back there instead. It might be better to complain about the profit the locals are making on the outrageously priced hotel rooms than worrying about whether they have enough to eat.

A night later, I'm with Tom and Lucy and Beth at a big party at Marina Hemingway. This is the place where people with biggish boats dock them when they come to Cuba and also the place where a lot of expatriates with boats live. It is a respite from the dilapidation of Havana, the sense of tragedy that underlies it. It looks like Southern Florida, with well-kept low-rise apartments set in green lawns and with an enormous swimming pool, tennis courts, nice cars in the parking lots. There are even Cuban families with dogs on leashes, well-groomed dogs whose ribs you cannot see.

The crowd is about half Americans and half well-heeled Cubans. I have come with Perrito in my beach bag, hoping to find someone to adopt him. But although there are Cubans with dogs on leashes in the crowd, it isn't easy. Either the people I approach say they have already adopted two strays or they look away as if I were going to ask them for change. I can't seem to find anyone. Then I do. He's a handsome Frenchman walking a white dog, impeccably groomed, who looks very similar to Perrito, but full grown. Would you know someone who might want him, I ask, hesitantly. "I'll take him," he answers quickly. He invites me to tea the next day but I cannot make it. I watch the two dogs, white and black, big and small, sniff each other, and then I walk back to my friends. Already I miss the weight of Perrito's small body in my arms. Perhaps, I think, this is the last time I will come to Cuba.

Shares