Seven years ago, Clay Logan, owner of Clay's Corner, the general store in Brasstown, N.C., counted all the possums killed on nearby roads. A few friends helped with the count, did some mysterious math and came up with a figure that would surpass any possible competing estimate. The town's title was born: Possum capital of the South.

For most North Carolinians to get to Brasstown, they must drive to the western end of the state, take a left and go along State Road 64. They will pass a brick millhouse being consumed by kudzu, a few horse farms and a thrift store, where proprietors discourage shoplifting with framed Bible verses: "For the ways of man are before/ the eyes of the Lord/ And he pondereth all his goings." Even then, they must continue beyond the illuminated advertisement for ammo standing out front of the local BP, and follow signs to the Brasstown Speedway where, during warm nights, stock car engines scream and echo off the surrounding mountains.

Arriving in Brasstown, then, they will notice the buildings lining Cherokee Creek -- a post office, a folk art gallery and Clay's Corner, a one-story white wooden building, with windows and a bench lining the front. Two gasoline pumps, under a metal canopy, stand between the store and road.

In addition to offering gasoline, groceries and auto parts, Clay's Corner gives Brasstown residents almost all the services they need: They can rent videos, weigh killed or captured game, hear bluegrass on Friday nights and celebrate civic events.

Clay's store also hosts the biggest New Year's Eve party in the region. Brasstown's population of 240 doubles when residents and guests celebrate the only way a possum capital knows how. The celebrations began at 10:30 a.m. this past Dec. 31, when a few men gathered behind a white trailer parked out front of Clay's. One, wearing a camouflage jacket, stuck his thumbs in his jean pockets and snickered while the others lit a neon-pink firework. It fired up and over Cherokee Creek, away from the gas pumps, and resounded into the surrounding farmland. "We just wanted to make sure they would work," Logan said, as he walked toward the store.

Half of one wall at Clay's is dedicated to opossum merchandise -- shirts, postcards, canned meat, videos of opossum hunts and bottled water. It sells briskly. The most popular items are those that hint at the evening's culminating event, in which Brasstown residents lower a caged marsupial from the store's gas station canopy.

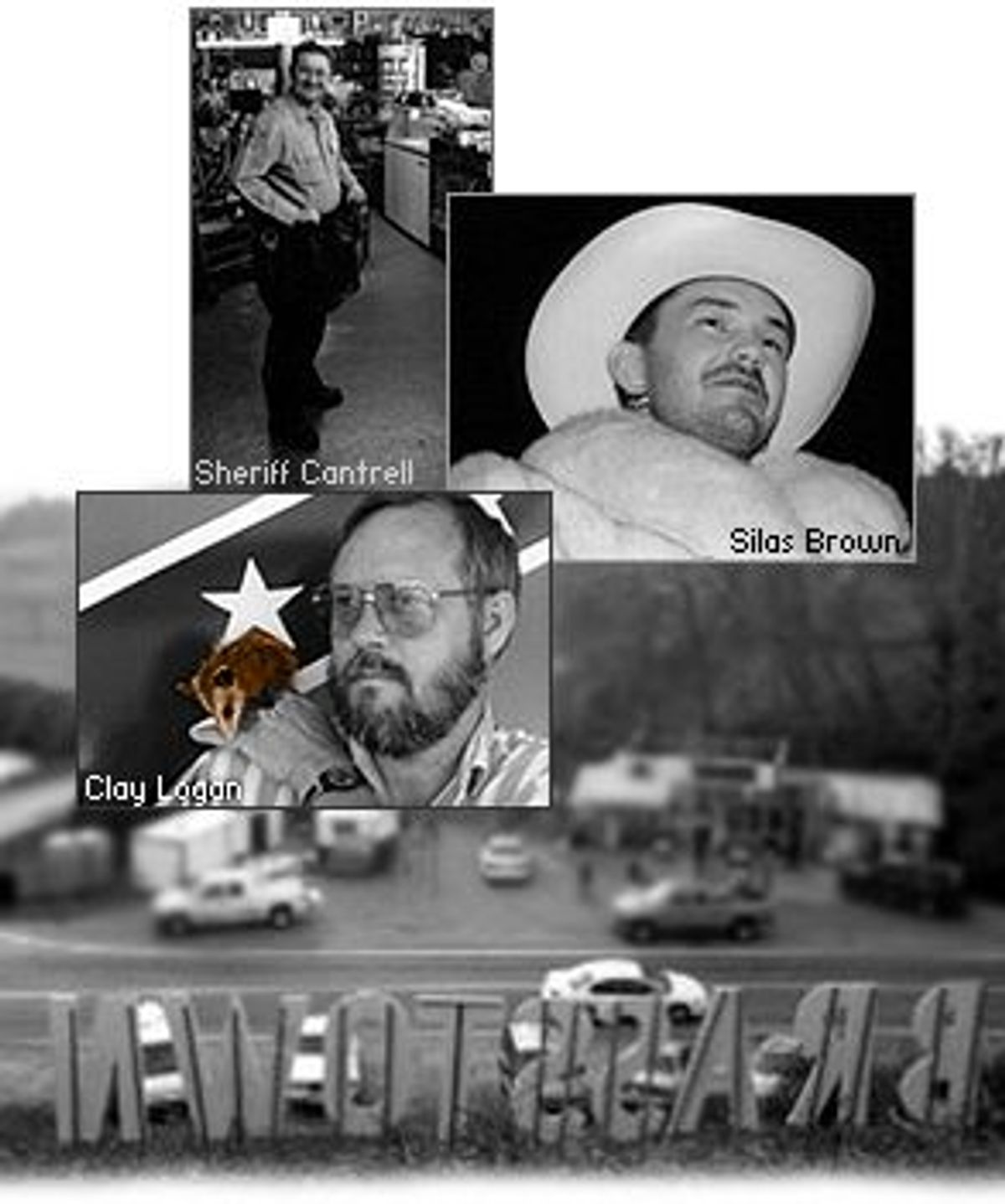

As Logan discussed the history of Brasstown's obsession with opossums, some Brasstown regulars stopped by: Charlene Thomas dropped off some cheddar sausage balls; Sheriff's Deputy Melvin Cantrell came by to pick up his costume; Bill Timpton, a local log-home builder and dairy farmer, stopped by to see if Clay needed some help setting up the stage.

Although it was a busy afternoon, Timpton said, most of these folks congregate at the store every day. They come in for coffee around 8, and then around noon they drop in for lunch and messages. "We use Judy as our secretary," he said of Judy Logan, Clay's wife. "She takes all the calls during the day and we come in during the afternoon to see if somebody's called and needs us when we're out working."

Brasstown made headlines for reasons other than opossums about three years ago when national media accused the town, and the region, of hiding Eric Rudolph, a prime suspect in the bombings of the 1996 Olympics and of abortion clinics in Atlanta. The neighboring community of Andrews was Rudolph's last known place of residence. His abandoned truck was found about three miles away from Clay's Corner, on Martin's Creek Road.

Cantrell, who stopped in the store Dec. 31, continues to work with the FBI search. He said the most intense portion of the investigation -- about three years ago -- revealed a disconnect between the federal organization and the small community.

"The FBI did not fit in well at all," he said. "They came here and really didn't get cooperation from the local people. They came in and tried to strong-arm people."

Their presence and tactics weren't even necessary, Cantrell says -- Rudolph could have been under arrest. "All they [the FBI] had to do was call Jack Thompson, who was sheriff of Cherokee County, and tell him where Rudolph was, what he did, and Jack would have been waiting on him."

Instead, Cantrell said, the FBI alerted the national media, which prompted Rudolph to flee. The suspect left his house so quickly that police found the lights on and the door wide open.

Logan says the FBI's presence had one good effect: Brasstown's economy soared with the long-term visitors. "Our economy was really a-booming," he said. "The restaurants stayed open late. The motel business was good." He then laughed and said, "We're thinking about resurfacing him to get the economy back up."

As folks at Clay's Corner prepared for the party outside the store, hanging lights, setting up stages and roping off the perimeter of the gas station, one of Brasstown's doctors, Bryan Mitchell, drove by in his pickup. He was on his way to Debbie and George Heilner's house, where he would meet up with other members of the Brasstown Brigade.

Dr. Mitchell is in his 50s, has a large white beard and speaks in a calm, deliberate voice. This evening would be the first time he had formally gathered with his friends in almost a month. A little over three weeks ago he had been in the hospital, having his prostate removed; since then he'd been lying in bed attached to a catheter. Mitchell was excited about the evening's festivities, and about putting the past year behind him.

When he pulled up the Heilners' driveway and parked behind some cars, gunfire sounded in the surrounding woods. For 15 years Mitchell and his friends have celebrated New Year's the same way -- visiting Brasstown homes, invoking a German chant of prosperity in front of the residents and then firing off their black-powder muskets. "It's strictly done in good fun and goodwill," he explained.

By the time Mitchell arrived, most of the other Brigades members had already gathered at the Heilners. There was Dave and Eldon Peters, a psychologist and his son; Kelly and Kenny Hyde, a registered nurse and state trooper; Leslie Kerlstein, a doctor; Keri and Laura Young, 17- and 14-year-old sisters; and Dan Stroup, another doctor and the man responsible for importing this ritual from Cherryville, his hometown in the North Carolina Piedmont region.

Stroup was especially excited because earlier in the day he had spoken with Don Yoder, professor emeritus of folk culture at the University of Pennsylvania, who described the history of the Brasstown ritual. It came from Germany, and the chant was originally written in High German. Participants started at midnight and went to every home's door. Sometimes residents would request extra symbolic measures, like shooting under fruit trees to invite fertility or firing something symbolic out of a cannon. Some attendees even used to cross-dress.

"Folks dressed up crazy," Stroup explained. "Men would dress up like women, and they would wear bells. And kids would wear masks. They called them bellsnickers."

When the Brigades arrived at the first house, Tom and Patsy Hudson's place, they gathered on their porch and began loading their muskets. Each removed a ramrod from the side of the musket's .50 caliber barrel, poured a film canister of black powder down the gun, followed by a cotton swab, and compressed it all with rapid stabbing motions, which emitted a loud, metallic shing-shing-shing.

Stroup then faced the Hudsons and recited the translated German prayer. A section of the 33-line text read: "We have this New Year's morning/ Called you by your name/ Since Christ for you has paid the whole/ You shall hear the art of science/ When we pull trigger and powder burns."

Afterwards, the members of the brigade walked to the end of the Hudsons' porch and swung their muskets into firing position. They held the guns at waist level, away from the body, because the kick is enough to dislocate a shoulder. Smoke shot out of the barrels, sometimes in perfect rolling rings, and the blasts echoed through the valley.

Their next stop was the Cherokee County School Board fundraiser and dance, which Dr. Mitchell said catered to the old money in Brasstown. Inside an auditorium, giant archways of blue and silver balloons crisscrossed a dance floor; punch flowed from a cascading fountain; a DJ, surrounded by party lights, played light music. The host, Julie Nix, who was wearing an open-shouldered, floor-length sequined dress, mingled cheerfully with attendees.

The crowd numbered no more than 10, but the members of the Brigade offered to "shoot them in" anyway. They did so outside, even adding shots from a cannon. Afterwards, they brought their guns back into the auditorium and ate hors d'oeuvres.

A few minutes later, and a few miles down the road, the Brasstown Brigade arrived at Clay's Corner to shoot in the New Year's Eve party there. Nearly 500 people stood around the stage. George introduced the group. "Although we appear to be a motley-appearing assemblage of variegated immigrants, of common attire, lacking regimental embellishment, we are vivacious and [have] colorful spirits second to none."

The speech, complicated in its rhetoric and purposely anachronistic, escaped many listeners' attention, who thought they had gathered to hear loud guns get fired.

The Possum drop officially began when a fire engine driving along State Road 64 turned on its sirens and red lights. Mike Logan, Clay's son, followed closely in his red semi. The attendees stood at attention and watched the procession. When the vehicles were directly in front of the gas station, the semi's doors swung open and about six hillbillies -- Clay's friends wearing straw hats, Billy Bob fake teeth and overalls -- jumped out and ran around crazily.

Then, from out of a small door in the semi, one hillbilly passed something to another. It was a Plexiglas pyramid, about a foot square at its base, adorned with gold tinsel. Inside, an opossum, alive but playing dead, lay surrounded by its own feces.

The crowd parted to let the hillbillies and their opossum through. Camera bulbs flashed as the hillbillies tied the cage to a string dangling beneath the metal Citgo canopy. They attached a glass disco ball to the bottom of the cage and hoisted the whole thing about three feet above the crowd. They tied the connecting string to a nearby post.

It was 19 degrees outside, and attendees stayed warm with hot chocolate and cigarettes. No one seemed concerned over the close proximity of fire and gasoline -- smokers puffed and flicked ashes by the pumps. Children huddled under three blazing kerosene heaters, resting above tanks of gasoline.

The first show, the annual Ms. Possum contest, featured seven local men dressed as women. First, Logan introduced last year's queen, Silas Brown. The young man stepped onto the stage with confidence. He wore earrings, a beaded necklace, a full-length fur coat and a cowboy hat. He walked across the stage, giving only coy glances to the screaming crowd.

The next contestant, Sheriff's Deputy Cantrell, emerged in a black vinyl miniskirt, wielding a police baton. As the next six contestants appeared on the stage, Logan incited the crowd: "Keep your clothes on," he yelled. He mimicked dancing with the men.

After the Ms. Possum contest, and a gospel choir's rendition of "The Road to Heaven," many of the celebrants wandered inside to warm themselves and peruse the tables of opossum merchandise. A bluegrass band had set up in the backroom, beside a wall of videos. One man, leaning against a life-size cardboard cutout of racecar driver Dale Earnhardt, nodded to the music so forcefully that he made the cutout's head bob back and forth.

At 15 minutes until midnight, the bluegrass band finished its last song, "I'm a Man of Constant Sorrow," and filed out of the store with the others. Outside, over loudspeakers, a record of John Wayne reading the Pledge of Allegiance became audible, while the patriotic text scrolled on a nearby movie screen. The Duke followed the speech with definitions for all of the pledge's important words. The crowd stood rapt and attentive. When Wayne's pledge was over, they all yelled, clapped and hollered.

As the end of 2001 approached, people moved toward the pumps and encircled the opossum's cage. The dead-still animal spun in its pyramid as the final seconds flashed on the distant movie screen. Someone took the string and dropped the opossum about six inches per second. At zero, it fell to its final position, seven feet off the ground: It was New Year's in Brasstown.

On top of the hill across the road from Clay's store, Jamie Logan and some others began setting off fireworks. Crowds, walking toward their cars, began ducking as purple sparks shot toward them. Then an unintended fire started on the hilltop. It grew to about the size of three chimney fires. The celebrants stared. Finally someone on the hill walked toward the fire and began stomping around its perimeter.

With the fire out, those still present could turn back to the movie screen, which bore the image of Robert E. Lee. The Confederate general sat in a regal pose on top of a gray horse, surrounded by his men. The image was replaced by a picture of an American flag and Confederate flag, lying across one another, with gold tassels at their tops.

The image was followed by a home movie depicting Logan and his friends dressed as hillbillies, strumming instruments in a barn. Playing as background to the strange scene was the song "I'm a Man of Constant Sorrow," excerpted from the "O Brother, Where Art Thou?" movie soundtrack. Clay and his friends appeared to be lip-synching to the lyrics.

The party was now breaking up. Clay stood near one of the kerosene heaters beside the store's front door. He was laughing with some folks when someone approached and asked, "What happens to the opossum?"

He said, "We let him out when the crowd goes away."

At about noon the following day, Dr. Mitchell stood in his kitchen as he watched a procession of cars pull into his driveway. It was the Brasstown Brigade, coming to shoot him in. Bryan greeted them and requested a change in the ceremony: He wanted to shoot something symbolic out of the cannon. He fetched his old catheter and loaded it into the iron barrel.

A few seconds later Stroup lit the cannon's short fuse. The catheter fired out of the barrel in a barrage of flames and landed in the branches of a nearby pine tree.

"I like that spot," Bryan said, looking into the branches. "I hope it stays there."

Shares