First: interminable demurrals, apologies, false starts, uncomfortable silences, a clearing of the throat, a shifting from foot to foot, why did I ever say I would do this, it always turns out badly, I have not read the French and Spanish, I cannot vouch for the translations, the surrealists were beyond interpretation, there is nothing new to be said, you must experience these poems yourself, I am merely a stenographer, I am hungry, I could be playing tennis, it's an unexpectedly gorgeous day, I am pleading with my wife to give herself to me but I promised to spend two hours at least writing, what if the poets' heirs come after me with knives?

For some it's baseball or politics or religion that sits at the back door night after night, where night after night you go out on the porch and say No, not yet, I'm not ready yet, half-hoping that the fate you would die for, the thing that says You belong to me, will get tired of waiting for you and seek another victim. For me it's poetry, the atom bomb of letters, the big Jesus in the garden.

So all this hemming and hawing is me just trying to be cheerful and aw-shucks about what is actually an endeavor of obeisance. Which is to say, before saying anything, that I bow, I scrape, I beg forgiveness, turn on my back, open my legs and offer up my throat to the poets who can make the moon rise in my heart.

I'm no scholar, no critic, not big on subtlety. I'm for poetry that can flatten you even when you're drunk, a poetry with the smash, crackle and pop of punk, the roar of rock, the noisy slap of love in a cheap hotel, the sensei's wake-up blow with that damn stick; I don't want to be getting out the slide rule.

And it's no good to be alone with your madness, to feel you're the only one in the room who sees the toothless woman with the Luger trimming her nails. So to read the work of inspired madmen is to experience a kind of communion, and to be inoculated with madness, like taking a tiny dose of subcutaneous laboratory-grade schizophrenia, to ward off the genuine heebie-jeebies.

Hey. Wake up. You were mumbling. Are you trying to write the whole review without mentioning the book?

So there was indeed a book, indeed there was, edited and translated by Mary Ann Caws ... I must have a snack. Some cheese and crackers.

Mary Ann Caws, the translator, teaches at City University of New York and has written other books including "The Surrealist Look: An Erotics of Encounter" and "Dora Maar With and Without Picasso: A Biography."

Listen to this by Thelonious Monk! (You can't hear that?) Sorry, have to take the poodle out. Be right back.

Ah. What glorious white dogs!

And so here in the church of the surrealist poets, as I was saying, the reader and the poet are conjoined by words.

"My love whose hair is woodfire," begins André Breton, leader of the surrealists. "Her thoughts heat lightning / Her waist an hourglass / My love an otter in the tiger's jaws / Her mouth a rosette bouquet of stars of the highest magnitude / Her teeth footprints of white mice on white earth."

Isn't that good? Oh, you can't hear that, can you? Oh, well, bend down there to your computer and maybe you can hear what I hear: "Her tongue a doll whose eyes close and open."

Did you ever go out with a woman whose breasts were molehills beneath the sea?

"My love her breasts molehills beneath the sea / Crucibles of rubies / Spectre of the dew-sparkled rose / My love whose belly unfurls the fan of every day / Its giant claws / Whose back is a bird's vertical flight / Whose back is quicksilver / Whose back is light." Oh, but there's more: "The nape of her neck is crushed stone and damp chalk / And the fall of a glass where we just drank ..." Help! I can't stop quoting! It's too gorgeous! "... My love ... / Whose hips are chandeliers and feathers / And the stems of white peacock plumes."

Enough of the great Breton? OK? You get it? Why? And why at Valentine's Day? Could it be that such derangement can rescue us from a torpor of the senses? That when in February the Romans filled the streets for Lupercalia they were still a little stiff and chilly from too much sleeping on the stone floors of Rome, and so had to create rites of extravagant sensuality? I don't know. But come dance with me, the days are getting longer.

If you just stopped right there and said That's enough, I must buy this book and read it aloud to my beloved under the sheets, at whatever the price (My copy doesn't seem to have a price on it) you'd be in good shape. But there are pictures too. Who is that nude, corpselike sleeping woman whose hair falls out of the picture onto the floor of our study, whose eyelashes are so brittle with detail you can feel them brush against your cheek but whose body is so soft with blur it's just like she was right here in front of us, so detailed in the face and yet so mysterious in her more passionate and alluring areas? That's a photograph by Jacques-André Boiffard, "Renée Jacobi," from 1930, it says in the back, and you could see it if you went to the Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, Musée national d'art moderne, I guess.

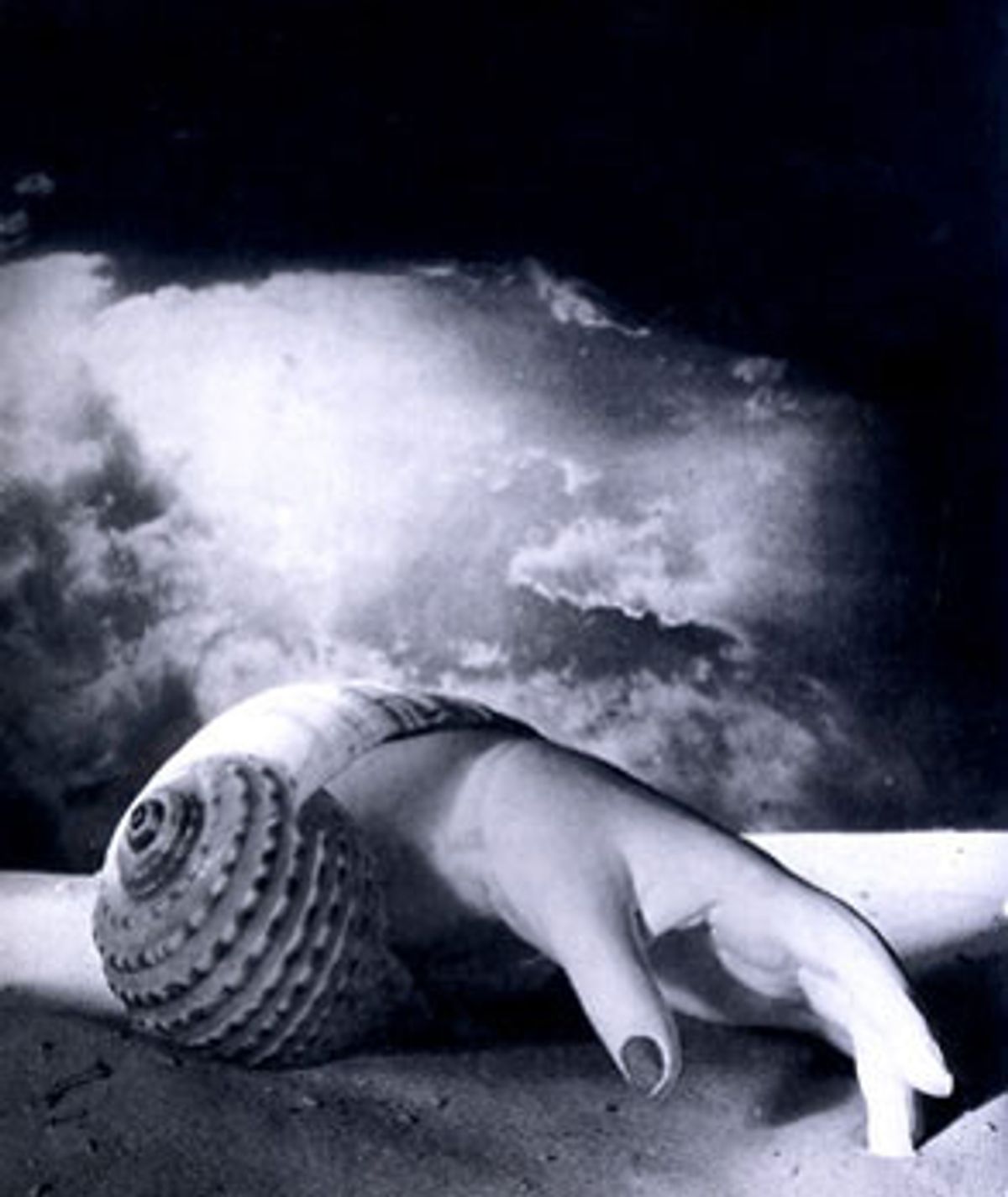

And there's this enormous weird hand crawling out of a snail shell by Dora Maar, too. And all through the book, while you're reading lines like "pilots steer according to my eyes / builders grow dizzy listening to me / architects leave for the desert / murderers bless me / flesh quivers at my call / the one I love does not listen to me / the one I love does not hear me / the one I love does not answer me" from "The Voice of Robert Desnos," you can look at that luscious untitled nude by Man Ray on approximately Page 63.

And if you demand an explanation, Caws provides one in her introductory essay, "The Poetics of Surrealist Love."

Had you forgotten, or didn't you realize, that surrealism got its start from the crazy dadaists? Ah, what glorious liberation from the ordinary did that troupe bring to the souls of early 20th century Europe (dadaism was founded in Zurich in 1915, she says). "The dadaists greatly enjoyed undoing every idea of the rational in favour of the violently active and highly coloured," she says. And they still do, I imagine, if you can still find one, what with rents so high. "Their performances included simultaneous readings of the same text in different languages, and combined outlandish costume with gesture, noise, art and drama."

In case you're bored with "The West Wing."

Oh, and maybe after so many Salvador Dalí paintings you'd forgotten that, as Caws says, "Surrealism began as a literary movement, visual art only being fully accepted when Breton later acknowledged that 'vision is the most powerful of the senses'' and downplayed the aural: 'Let the curtain fall on the orchestra.'"

Wouldn't it be great to live in a world where guys with mustaches ran around saying, "Let the curtain fall on the orchestra"? Well, I guess that's why so many of us fled the suburbs for the great American cities, hoping to find crazy guys with mustaches and manifestos. It's still a dream worth pursuing: to find a dark basement club where the only light comes from the spark of the new. Especially now: This is no time to become a bond salesman. Why not light out for the territories, culturally speaking? These poems, and Caws' condensed history of surrealism, provide a wonderful reminder of how powerful and necessary are the voices of the irrational.

Know what I mean?

Oh, but there's so much more, now that the dogs are walked and I've got some coffee, and Monk and Mulligan have moved on to "I Mean You" (take 4). Sure you can't hear that? Here, I'll turn it up.

"Surrealism laid great stress on the liberating power of sexuality, which found a firm support in the texts of Sigmund Freud. Breton's text 'Mad Love' (L'Amour fou), published in 1937, illustrates how for Freud, sexual love 'breaks the collective links created by race, rises above national differences and social hierarchies.'" Caws explains how the French surrealists' desire for freedom "linked the surrealist revolution with the French Revolution two centuries before."

It's a good 10-page introduction to about 100 pages of poems by such greats as the aforementioned Breton and Desnos but also by Pablo Picasso, Salvador Dalí, Frida Kahlo, Paul Eluard, Octavio Paz and others.

I wish I could say I have a favorite. That would indicate that I have at least some critical faculties, wouldn't it? That I could at least make a few comparative judgments? Let me just instead quote some more of the more beautiful and interesting lines.

From Octavio Paz in "Clear Night" (extract): "your name is downpour and your name is meadow / your name is high tide / you have all the names of water / But your sex is unnameable / the other face of being / the other face of time"

From Benjamin Péret in "Wink": "Parakeets fly through my head when I see you in profile / and the greasy sky streaks with blue flashes / tracing your name in all directions."

Many of the poems seem to be incantations or chants, rather than arguments, and work by the accretion of images, so that at the conclusion what is left in the mind is not a single unified vision but a collection of disparate objects. It's like the poets are in your head, up on ladders, painting on your brain. For instance, in Péret's incantatory "Hello": "my opal snail my air mosquito / my quilt of birds of paradise my hair of black foam / my tomb burst open my red grasshopper rain / my flying island my turquoise grape."

Or in Picasso's "Her Great Thighs," a sort of catalog of her body parts -- "her hips / her buttocks / her arms," etc., is followed by a more wide-ranging collection of things: "the oil lamps and the little bells of the sugared canaries between the figures -- the milk bowl of feathers, snatched from every laugh undressing the nude from the weight of the arms taken away from the blooms of the vegetable garden ..."

So what the poem invents is not so much a narrative or an argument as a strange machine, or a painting or sculpture of the world, things not held together by functional or narrative relationship but by unconscious associations they have for the poet, or by a visual or tactile affinity. These are exotic recipes for a strange feast.

And finally, ladies and gentlemen, I will make a pronouncement, I will say that there is a good reason this book exists, I will place it in context, I will suggest that it serves some purpose in our culture, that it reminds us to do something we had neglected to do, that it stands in relation to something, that it sheds new light on something formerly in shadow, that it is something to look through to see something else, that it is indeed something, that it is more than something, that it is more than what it appears to be, that it is an important reminder, that it is important in and of itself, that it is necessary, that it is essential, that we cannot believe we lasted this long without it.

Then I will get a snack.

Shares