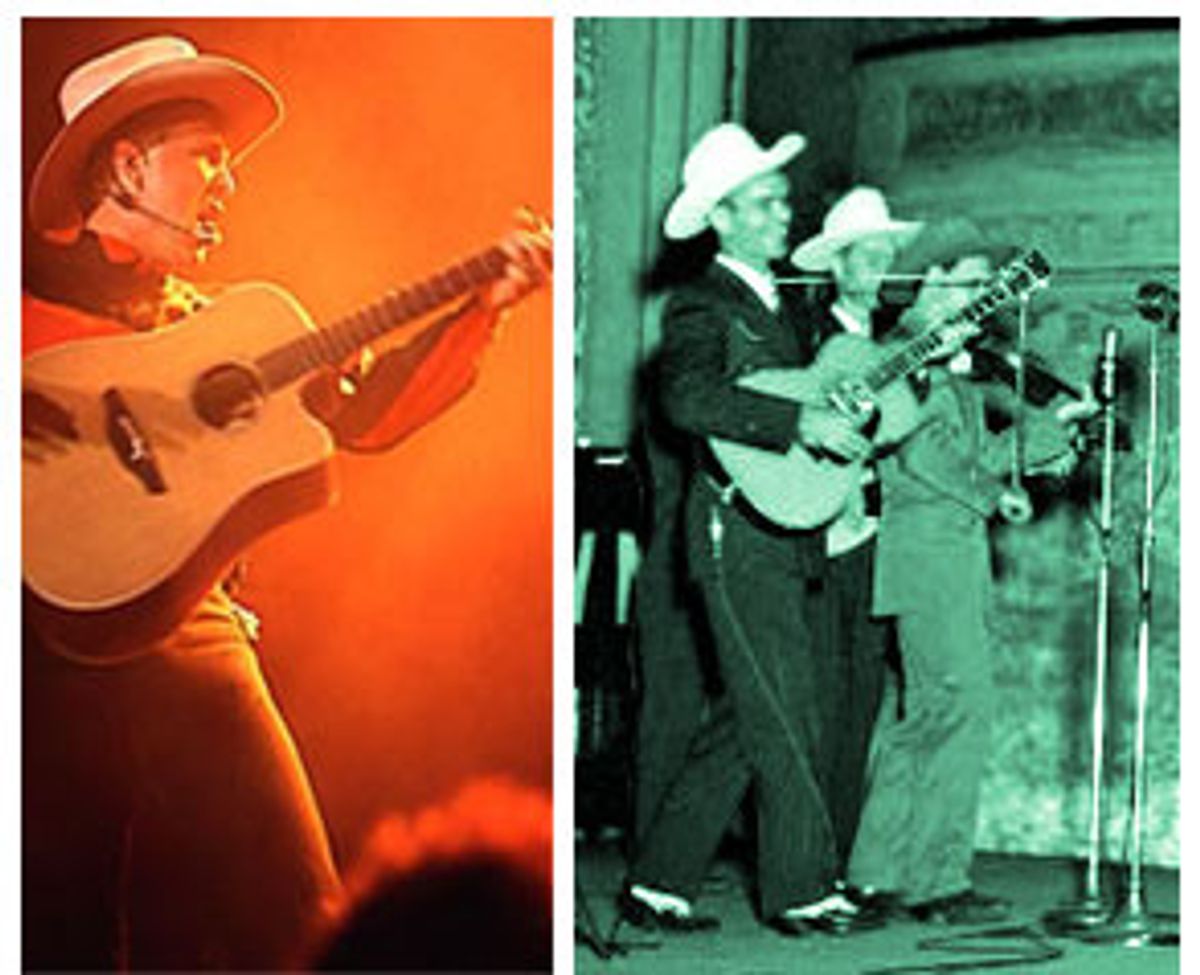

If Shania Twain had danced on Hank Williams' grave in spike heels and bustier, it would not have sparked a firestorm like the one that hit the Country Music Foundation when it fired Ronnie Pugh last fall. Most country music fans -- let alone nonfans -- have never heard of Pugh. But to pop-culture scholars, entertainment writers and editorial fact-checkers, the affable, low-key Texan was pretty much the guy who knew everything.

The CMF is the not-for-profit organization that owns and operates the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum in Nashville, Tenn., which, besides being a tourist magnet, also houses the world's largest collection of country recordings and reference material. With Pugh gone, scholars fear there is no one left to steer them intelligently through this labyrinth of vital information. The foundation has yet to prove otherwise.

Pugh had been at the foundation 22 years, doing basic library work and assisting in special projects, when, on Sept. 7, CMF director Kyle Young summarily dismissed him. It was a bloody day all around. Also sent packing were Chris Dickinson, the much-admired editor of the Journal of Country Music, and three lower-level staffers. Young told Pugh and Dickinson he was doing away with the special projects department for which they worked.

On Sept. 16, Charles Wolfe, a country music historian and professor of English at Middle Tennessee State University, sounded the alarm in an open letter sent to various colleagues and posted on the Internet. "The Country Music Foundation Library and Archives has been severely decimated," Wolfe wrote. To underscore this indignity, he noted -- incorrectly as it turned out -- that Pugh "was given an hour to leave the premises [and] escorted outside by a security guard."

Dickinson's exit, Wolfe said, raised the specter that "the Journal of Country Music will be changed from its present form and stripped of any historical material and turned into a slick Garthian [as in Garth Brooks] fan magazine, full of eye candy for the high rollers who contribute to the [Hall of Fame]." He urged those who agreed with him to protest the firings to the CMF's board chairman and president.

And the protests rolled in. Richard D. Smith, author of the Gleason Award-winning "Can't You Hear Me Callin'," a biography of bluegrass pioneer Bill Monroe, told the board's leaders, "I am genuinely afraid that -- under the command of the persons responsible for these firings -- the CMF will abandon its world-renowned commitment to country music history and scholarship. The brutal fact is that this will reflect very badly on you gentlemen in years to come since it happened on your watch."

"The actions of [the Hall of Fame] administration," wrote James E. Akenson, co-chairman of the International Country Music Conference, "show that they do not know the meaning of the word loyalty, nor do they understand the marvelous contributions of Ronnie Pugh to the [Hall of Fame] mission."

Nolan Porterfield, the eminent Jimmie Rodgers scholar, proclaimed, "I know of no more asinine move than the firing of Ronnie Pugh. Chris Dickinson, with whom I have worked on several projects for the Journal, is the finest writer and editor they'll ever have. It's a severe insult to anyone who genuinely cares about country music and its history. The Board of Trustees, it seems to me, has an obligation to correct this situation. Until that happens, you may be sure that I will take every opportunity to speak negatively and harshly about the Country Music Foundation and Hall of Fame."

The fact that Porterfield could muster up no worse threat than bad-mouthing the CMF illustrated the box Pugh's supporters found themselves in. No matter how outraged they were, they could hardly boycott their single most important reference source. It remains unclear whether the foundation is trying to remake itself in some more commercial, less historical image, but fans and scholars of traditional country are watching anxiously. At the very least, the CMF faces an ugly public relations gaffe, one that could affect contributions and grants, as well as sully its standing among research institutions.

Hoping to still the growing turbulence, Young dispatched a letter to Wolfe on Sept. 17 and sent copies of it to all the others who had lodged complaints at Wolfe's urging. Young's response took the high road: "I share your respect and appreciation for Ronnie Pugh and Chris Dickinson, two sticklers for the facts who each made important contributions here and who are deeply appreciated." What Young's letter did not do, however, was explain why he found such "appreciated" employees so dispensable.

The CMF suffered another blow when Bob Pinson, the only other scholar on staff in Pugh's encyclopedic league, announced he was quitting in support of his colleague. Pinson had already been easing into retirement and was working only part-time at the foundation, mostly helping Pugh prepare a massive discography of pre-World War II country music for Oxford University Press. They were only days away from completing the job when the ax fell.

To those who knew the principal players, the dismissals were as mystifying as they were outrageous. Did this signal a shift from the historical to the promotional in the CMF's mission? No, said the foundation, pointing to an array of upcoming scholarly projects. Were Pugh and Dickinson let go to save money? Perhaps. The Hall of Fame and Museum had just moved into a block-long, $37 million temple in downtown Nashville and tourists weren't exactly flocking in. Was it something personal between Young and the outcasts?

Pugh traces his "troubles" with the foundation to the regime of Bill Ivey, Young's close friend and predecessor at the institution, who left in 1998 to become chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts. Pugh had written a book on Ernest Tubb, the great Texas singer and bandleader, and given the CMF the option to publish it. The foundation declined. Soon after, Duke University Press snapped up the manuscript and, in 1996, published "Ernest Tubb: The Texas Troubadour" to near universal academic acclaim. "Still," says Pugh, "they sort of faulted me then for going outside. It was like I was trying to make a name on my own and not being a team player."

In November 1999, Pugh asked Young to relieve him of his duties as head reference librarian. "I had grown tired of it," he says. "The problem is that in nearly 20 years, you get asked the same questions many, many times." Young moved him into special projects, where he worked on fact-checking for the Journal of Country Music, proofreading books for CMF's joint publishing venture with Vanderbilt University and doing research for exhibits at the new museum.

One project CMF and Vanderbilt had in the pipeline on Sept. 7 was Pugh's proposal for a book on country music and politics. The joint press had already paid him a small advance. Young offered to go forward with the book even after firing Pugh, but the latter declined. (He has since placed the project with another publisher.)

"My official conversations in Kyle's office," Pugh says, "were never pleasant, never friendly, always some sort of reprimand. I got into trouble over some comments to the [Country Music Association] regarding potential Hall of Fame nominees they sent by us. I made it plain that I thought some of them were rather ridiculous in [suggesting] people like Patti Page. It was an absolute travesty. He called me on the carpet for that."

Young also forbade Pugh and other staffers -- regardless of their stature -- from responding directly to questions from the public and the press. Everyone seeking information had to be referred to the foundation's outside publicist, who then determined which staffer could best answer the inquiries. "They were just totally paranoid about the press," Pugh says. "Even Ivey never did that."

When the foundation moved to its new location last May, Pugh, Pinson and other veteran staff researchers learned they would not even be issued keys to the museum's archives, even though they had helped build them and used them constantly in their work. To access the collection, they had to track down a librarian and ask to be let in.

Young won't discuss the specifics of the firings. But he says there are good reasons for the restrictions he imposed. "We get a lot of calls on a lot of subjects, and this is a complicated place," he points out. "Some questions are financial, some have to do with tourism, some have to do with the history of the music. So what we do is channel the calls directly to [the publicist] so that we will know that the media get a timely response and that they get connected to the right person. To my way of thinking, it's not about restricting access, it's about creating access."

On the matter of keys to the collection, Young notes, "I don't have a key." He contends that this particular safeguard is dictated by the larger size and increased functions of the new building. "In the old place, we had 22 people. Now we have about 50 full-time employees, and a couple of hundred people working in this building every day. So security in general is different. We used to operate on a couple of million dollars a year; now we're looking at about $11 million a year. We're spending about $230,000 a year on security alone."

Young admits that money is tight at the CMF. "We opened in a real tough time," he says. "We know now that we were in a recession. Then there's the war and the fact that the country music industry is not exactly thriving. But we are meeting budget. Attendance is not exactly what we expected, but the great thing about this place is there are lots of sources of revenue. We are not a one-trick pony."

To reassure doubters, Young ticks off a series of serious projects nearing completion. These include the publication of "Singing in the Saddle," Doug Green's study of western music and singing cowboys, and the issuance of a revised edition of Mary A. Bufwack and Robert K. Oermann's out-of-print classic on women in country music, "Finding Her Voice." On the record front, the foundation is plumbing its archives to release annotated CDs of live radio performances by Chet Atkins, Eddy Arnold, Loretta Lynn, Carl Smith and others. Young stresses that the discography Pugh and Pinson were working on will be published in 2003 as scheduled. For the time being, the Journal of Country Music, which usually fields three issues a year, will be assigned to freelance editors.

Pugh says he doesn't know what he will do next. He's applied for library jobs and has gotten his real estate license. Then, of course, there's his book on country and politics to finish. Dickinson has moved to Chicago and is contributing articles on country music to the Chicago Tribune and writing her own book.

Wolfe, meanwhile, views the foundation's efforts to mend fences with considerable skepticism, although there are no plans so far to chuck out the archives and replace them with a display of Garth Brooks and Billy Ray Cyrus' Stetson hats. "I know how weird and quirky that collection is," he says." A lot of times what myself and other people would do is go up to Ronnie and say, 'Here's what I'm working on. What do I need to look at?' And Ronnie would just sit there and rattle off stuff that would never show up in a computer search. That's what they've lost."

Shares