At some point in his or her career, every writer probably hits a wall where he wonders if he has anything left to say that he has not said already, and better. Fifty-four-year-old Stephen King, author of over 40 novels, thinks he may have reached that watershed. “That’s it,” he told the Los Angeles Times last week. “I’m done. You get to a point where you get to the edges of a room, and you can go back and go where you’ve been and basically recycle stuff.”

Better, King suggested, to lower the curtain on a truly dramatic career.

For legions of fans addicted to devouring a new King tome every six months or so, his self-exile would be a devastating loss. But they should not abandon all hope. King has spoken of retirement before, and his agent, Arthur Green, told the Associated Press, “I think it’s unlikely he’ll stop working.”

King’s retirement may be unlikely, but it’s not a bad idea. In fact, it’s a great idea. Truth is, King hasn’t reached the point of recycling; he’s been recycling for years. His fans may not want to admit it, but Stephen King’s most recent books are dull, dreary, repetitive, unoriginal, uninspired hack work. And the best thing — perhaps the only thing — that King can do about it is to stop writing.

Don’t think I enjoy saying that. I’ve been reading King novels over the course of three decades now, and I’ve never felt apologetic about doing so — never felt defensive about his, shall we say, unpolished literary gifts, or the validity of the horror genre, or what my love for his talents said about my own maturity and mental health.

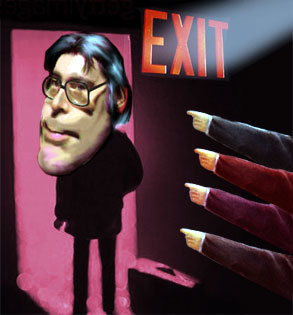

For me, getting scared by King was one of life’s necessary escapes. I remember buying “Salem’s Lot” from a supermarket checkout rack when I was 12 years old. I read the book, which is about vampires taking over a small Maine town, in the bedroom of a lonely, creaky house on the wind-buffeted tip of an Atlantic island. My bedroom was the only one on its floor, and I would read the book before going to sleep. When I turned the lights off and the wind-blown branches scraped against my curtainless window, I’d shiver and wonder if, just possibly, just maybe, there weren’t vampires scratching the glass with their dirty fingernails, begging to be let in, longing to feed … on me.

I imagine anyone who’s read a Stephen King novel has experienced a similar moment where, if only briefly, horror and reality blur. The unsettling force of King’s powers of persuasion — maybe there really are monsters outside the window — has sent some readers I know scurrying back to the more secure, high-walled realms of highbrow literature. Others, like me, get hooked on the intensity of being scared, the adrenaline of terror. We are safely scared, though. We know that when we finish a King novel, the worst terrors will have been averted, the protagonists will be victorious (though not usually without casualties) and in any case, our own problems are not nearly as horrible as what happens to the characters in King-world.

And so, after racing through “Salem’s Lot,” I read gleefully on, back to King’s first novel, “Carrie,” a pulp classic, then forward to “The Shining,” which I read in the backseat of a station wagon while a friend’s mother drove a fellow ninth-grader and me to Walt Disney World. Thanks to King, I didn’t know the streets of my own suburban hometown until I got my driver’s license and was required to look out the window.

With memorable characters and strong plots, “Carrie” and “The Shining” were great reads. So were subsequent books such as “Firestarter,” “The Dead Zone,” “The Stand,” “The Talisman” and “It.” They featured a variety of terrors: telekinesis, a haunted hotel, Satanic villains. But all of them worked because King recognized our most basic fear: that some monster, figurative or literal, will invade our daily existence and deprive us of our opportunity to seek — and find — happiness. As in that old horror myth about the threatening phone calls that turn out to be made from the attic, the real monsters in King’s fiction lie very close to home: In both “Carrie” and “The Shining,” for example, the greatest violence is inflicted by the protagonists’ parents.

“Horror” was always a reductive label for King’s work, for all its guts and gore; his best books are more like Gothic tragedy, in which fulfillment is yanked away from characters just as they think they’ve finally found it. In “Carrie,” Carrie White’s chance to become accepted by her high school peers is cruelly stolen from her just as she’s finally allowed herself to trust the possibility of happiness. Naturally, much death and destruction result.

In “The Dead Zone,” John Smith — King likes everyman names — meets the girl of his dreams, only to lose her the very same night when a car crash plunges him into a prolonged coma. For Larry Underwood in “The Stand,” tragedy comes just as the Huey Lewis-like rocker has finally found his personal Jesus: a hit single. Unfortunately, even as his song is climbing the charts, a deadly virus is wiping out 99.8 percent of the population. Not good for sales.

The real intruders in King books aren’t usually so grandiose as a plague. His genius — yes, he did have a kind of genius — was his intuitive understanding that, more than any imagined monster, it’s the terrors of everyday life that truly frighten. Poverty. Cancer. Alcoholism. Spousal abuse. The loss of a child, as in “Pet Sematary.”

His happy endings were what made King so redemptive. By creating monsters who could be slain, King always gave his characters — and his readers — a way to fight back, a happy (or at least a bittersweet) ending; he helped us put a stake in the vampires scratching at our window. Stephen King gave his readers hope.

It’s hard to say exactly where King lost his way, but at some point in the late 1980s, his books became increasingly less distinctive. I remember his early works vividly. But I can’t name a character from “The Tommyknockers,” “Gerald’s Game,” “Insomnia,” “Rose Madder,” “The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon,” “Needful Things” or “The Langoliers.” In those second-tier works, plots and themes were repeated from earlier, better King books, and characters became types rather than people. How could they not, really? By this point King was well into double-digit novel production. Judging by his sales, his fans didn’t seem to care that the books were less and less compelling. Why should he?

King’s most interesting books of the 1990s give some hint as to what might have been going on. In one way or another, they all focus on the horrors of literary success beyond his wildest imagination. In “The Dark Half,” King’s protagonist is a bestselling writer whose sadistic doppelganger comes to life when he tries to stop writing. In “Misery,” another bestselling writer is taken hostage by a rabid fan, who disapproves of the writer’s attempt to kill off a serial character. And in “Bag of Bones,” yet another bestselling writer stops writing.

It’s never a good sign when a writer gives up writing about the problems in his readers’ lives and starts writing about the burdens of success. King is said to have an excellent relationship with his many readers, but the evidence that he feels harassed by his large, loyal and hungry fan base (are the fans the real bloodsuckers?) is ubiquitous.

Consider the series of questions and answers his Web site, StephenKing.com, provides for fans. “Will he read my manuscript?” Nope. “To avoid any litigation problems, he has been advised by his agents not to look at any manuscript that has not been accepted by a publisher.” Does he accept story ideas? “To avoid any litigation problems, he has been advised … ” Can he help find an agent? “There being some legal problems with this … ” You get the picture. King has built a tall, spiked, wrought-iron fence around himself, and hung a “Beware of (Rabid) Dog” sign on it.

Or maybe his devoted readers built it for him. It’s hard not to be sympathetic to King’s plight — at least as sympathetic as one can be to a writer who’s earned over one hundred million dollars in his career. I do not doubt that people exist who, in a bogus attempt to make a fast buck, would claim that King read and stole their story idea. And the nature of King’s material pretty much guarantees that some of his readers are going to be a little, well, odd.

Still, one gets the feeling that King’s efforts at isolation are about more than legal concerns. King feels so imposed upon by his audience that he has to tell them, in books such as “Misery,” to back off — they’re losing their grip on reality. They have become the ones scaring him.(And there are a lot of more of them than of King.) But it doesn’t work: The readers make even these passive-aggressive books massive bestsellers. So King resorts to less artistic forms of self-defense.

A couple years ago, my sister and brother-in-law spotted King at a Washington, D.C., restaurant. (With his spiky black hair, weirdly wide eyes, and semiskeletal features, he’s pretty distinctive.) Thinking that I might like an autograph, they approached him and said politely, “Excuse me — are you Stephen King?” A little intrusive, perhaps, but not terribly; my siblings are polite people, and distinctly non-threatening.

King looked at them, uttered a flat “No,” and turned away. End of conversation.

My siblings wouldn’t have been offended if King had declined their request for an autograph. What startled them was that he was rude and dishonest to people who, for all he knew, had done nothing other than contribute to his children’s college tuition fund. Unless you’re in the Sex Pistols, showing contempt for your fans is never good marketing strategy.

For any writer, however, death is a great career move, and in June 1999 King almost obliged. While walking down a country road in Maine, he was hit by a van driven by one Bryan Smith — a very King-like name — who was, at the time he hit King, reaching into the backseat to push his Rottweiler, Bullet, away from a cooler of meat. (His other Rottweiler was named Pistol.)

In King’s subsequent recounting of the story, Smith was semi-coherent when he came to find the man he’d hit, appearing not to realize what he’d done. With his normal name, odd behavior and scary dogs, Smith resembled one of Stephen King’s deranged characters. Or one of his fans. Increasingly, they’re the same thing.

The bad news is that King was nearly killed. The good news, for King, was that the experience prompted the arbiters of elite culture to consider him with a new generosity. A recovering King became the critics’ darling. Soon King was mingling with a more sophisticated breed of fan — not the kind who picks up a cheap paperback at the supermarket and throws it into her cart with the Jif and Cinnamon Toast Crunch, but the kind of reader who might avidly devour the New Yorker profile of King, then hide his books when guests came over for supper.

In 2000, the New Yorker also invited King to grace its 75th anniversary series of author readings. Following trendy short story writer Matt Klamm at the grunge-chic Bowery Ballroom, King made what he said was his first public appearance after the accident. Leaning heavily on a cane, he hobbled on stage looking frail and vulnerable and surprisingly old. The audience gave him (rather ironically, I thought) a standing ovation. King promptly announced that the battered glasses he was wearing were the same ones that he’d worn on the day of the accident. They’d been knocked off in the collision and landed, strangely, in the front seat of Smith’s van. The crowd loved this gruesome detail — as King knew it would. I couldn’t help but wonder if it were true.

Not coincidentally, the same tidbit shows up in “On Writing,” a combination writing manual/literary biography King published in 2000. “The frames were bent and twisted, but the lenses were unbroken,” King wrote. “They are the lenses I’m wearing now, as I write this.” What, I thought, did those glasses represent to King?

Being hit by a van could have been — should have been — King’s midlife heart attack, the sign from above that tells the victim, Hey, there’s more to life than the daily grind. Instead, in “On Writing,” King details how, five weeks after the accident, he began writing again. He set up his trusty Powerbook, propped himself up next to a fan, and wrote for an hour and 40 minutes before the pain in his hip got too great. “When it was over, I was dripping with sweat and almost too exhausted to sit up straight in my wheelchair.”

Although I suspect it’s a composite story, an artificial narrative, it’s certainly a moving one; King hadn’t gone five weeks without writing since, probably, he knew how to write, and the experience of sitting before the keyboard and staring at an empty screen after such an unwanted interruption must have been terrifying. The description of it — as with all of King’s portrayals of the writer’s life — certainly is.

The work that followed, however, was less successfully realized. His first novel after the accident was “Dreamcatcher,” the story of four men hunting in Maine woods when aliens invade. The men fight back, using telekinesis that they have possessed since adolescence — traces of “Carrie” — when they intervened to save a mentally retarded child from bullies.

“Dreamcatcher” is over 700 pages long, and it is incomprehensible. It reads like a jumbled, slapped-together collage of King’s past work. The aliens? “Tommyknockers.” Lost in the woods? “Tom Gordon” and “The Railroad.” The mysterious government forces who converge on the area to eradicate the invaders and all who’ve seen them? “Firestarter” and “The Stand.” It’s all been done before, by King himself — and better.

“Dreamcatcher” also suffers from embarrassingly flimsy efforts at characterization. The protagonists’ names are Beaver, Henry, Jonesy and Pete, which is taking the Everyman thing a little too far. It’s just lazy. These men have been barely introduced to us when the action kicks in, and when Beav and Pete get knocked off in the first hundred pages or so, it seems as if King himself doesn’t care about their fate. (And if he doesn’t, why should we?)

We’re left with Jonesy and Henry, who are so exactly alike — and so like so many other King heroes — that I couldn’t tell them apart through the next 500 pages. I’d keep reminding myself: “Henry, he’s the one with the alien in his head, that’s right.” Well, no. That was Jonesy.

And then there’s that problem of Duddits, the retarded boy with psychic powers. The simple savior is a recurring and weary trope in King’s fiction. Usually, however — and somewhat disturbingly — the saintly simpletons are black characters, pretty much the only black characters in King, such as the cook in “The Shining,” Speedy in “The Talisman” and Mother Abigail Freemantle, the Christ-like old woman in “The Stand.”

Or, sometimes, the black character and the mentally retarded character are merged into a sort of supersaint, such as the angelic John Coffey in “The Green Mile.” King is on shaky ground here. Could it be coincidence that Maine, his longtime home, has virtually no African-Americans? If King weren’t a well-known liberal, would we call these characterizations racist?

An incoherent plot, translucent characters, self-plagiarism — these are not the only flaws in “Dreamcatcher.” More worrisome for King in the long run is the pop culture problem. King is a baby boomer, and he’s always had a dead-on sense of middle-class boomer taste — which, I think, is one reason so many readers feel connected to King and his books. In his pages, they see themselves.

But in “Dreamcatcher,” I noticed something I’d never seen in King before: King’s middlebrow references felt dated and off-key. When an army of helicopter-flying hit men cue their soundtrack — hasn’t King seen any movies since “Apocalypse Now”? — the song they play is “Sympathy for the Devil.” Except that these days, it wouldn’t be. Our boys in Afghanistan aren’t playing Vietnam-era Stones. They’re listening to Outkast and Kid Rock.

If you like King, seeing him age like this is painful; it’s like watching a great athlete lose a step, or senior citizens try to boogie at a rockin’ wedding reception. King could fix the problem, but he’d have to work at it, and he’s no Tom Wolfe. In fact, he’s never really reported at all. His world comes from his experiences and his imagination. And when you spend every day of the year writing, as King has said he does, in a fenced-off house in an isolated state where it’s winter for about nine months of the year, and you’re cranking out books like a roomful of monkeys, you’re going to run low on original material. It’s just a matter of time. King only lasted longer than most.

“Dreamcatcher” was followed by “Black House,” a sequel to “The Talisman,” and if “Dreamcatcher” could have been chalked up to post-accident jitters, there’s no excuse for “Black House.” It’s an atrocious piece of work. (As “The Talisman” was, “Black House” was co-written with Peter Straub, but the book feels dominated by King.) Some of the problems are the same: flimsy characters, lazy plotting. There is only a token attempt to connect “Black House” to “The Talisman,” as if King has simply taken it for granted that if you’re reading the second, you read the first. Frankly, anyone who hadn’t read the first wouldn’t have a clue what was happening in the second.

It’s possible that King’s remarkable imagination — surely one of the most fertile in American literature — has finally grown barren. In both “Dreamcatcher” and “Black House,” he resorts to cheap vulgarity and violence far more repulsive and over-the-top than anything in his best books. “Dreamcatcher” features “shit-weasels” who grow in victims’ stomachs, then — after the victim suffers prolonged and odiferous farting — eat their way out of the victims’ anuses. (Okay, King also saw “Alien.”) How charming. The plot of “Black House” hinges on the cannibalization of young children; apparently the flesh of the buttock is the most tender. Even for a King fan, this is beyond the pale. It reeks of creative desperation and verges on pornography.

Ideally, the writer-reader relationship is a symbiotic one. But King seems to be taking his readers for granted. His impatience with the role of celebrity author and his new, post-Bryan Smith appreciation for life have made him resent all those demanding little people who made him rich and famous. In “On Writing,” King declares that “Life isn’t a support system for art. It’s the other way around.” I’m not quite sure what that means, but it sounds to me like King needs to get a life.

Not knowing what else to do but write, and happy to keep the money pipeline open — “Black House” reads like a Hollywood sequel, manufactured solely to cash in on a far superior predecessor — King still keeps the books coming. Even if he stops now, he’s got enough manuscripts in the drawer for years of new material.

But he’s not writing. He’s shoveling, and asking us to grin and swallow it. Better for Stephen King to stop publishing altogether than to keep churning out crap, like a shit-weasel, eating its inexorable way through our insides, making us not King’s fans but his victims.