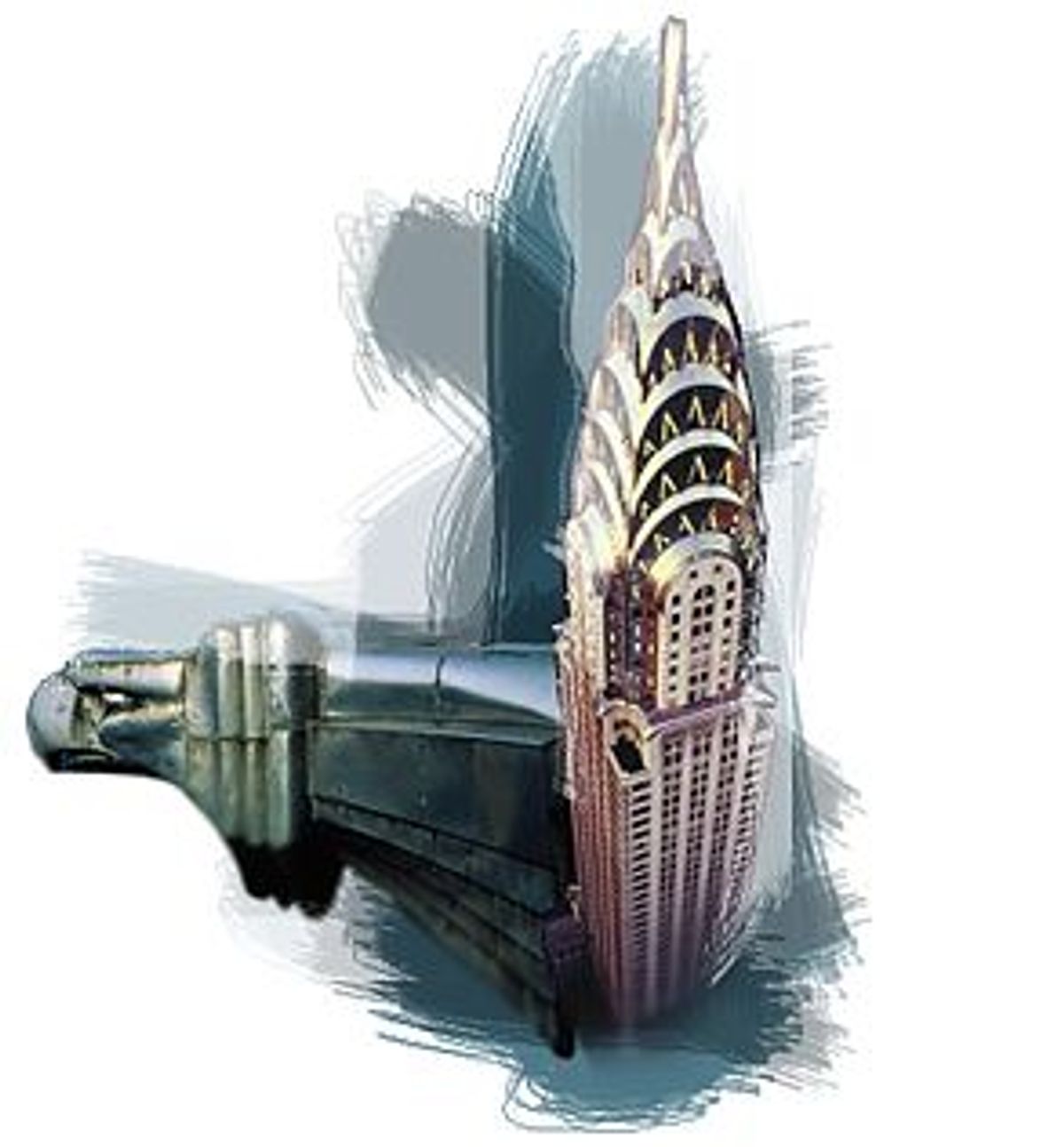

Forget that the Chrysler Building went up more than 70 years ago. In daylight, with its stainless-steel crown gleaming in the sun, or at night, when the triangular windows of that crown are lit up, lined up in seven curving rows that overlap like fish scales as they stretch up to that swordfish-nose spire, the Chrysler Building always looks like the future. It's Jazz Age poetry, rendered timeless by the ever-changing sky around it.

Architects, who have both intuition and training on their side, have some very good reasons for loving the Chrysler Building. The rest of us love it beyond reason, for its streamlined majesty and its inherent sense of optimism and promise for the future, but mostly for its shimmery, welcoming beauty -- a beauty that speaks of humor and elegance in equal measures, like a Noel Coward play.

How can a mere building make so many people so happy -- particularly so many ornery New Yorkers, who often pretend, as part of their act, not to like anything? There may be New Yorkers who dislike the Chrysler Building, but they rarely step forward in public. To do so would only invite derision and disbelief. The Chrysler Building is shorter than its fellow art deco triumph, the Empire State Building (which took its place as the tallest building in the world only a few months after the Chrysler's completion), but it looks so much more significant. The Chrysler Building is indisputably the gem of the city's skyline. In his small and wonderful book "The Look of Architecture," critic Witold Rybczynski calls the exterior of the Empire State Building "the architectural equivalent of a gray flannel suit." The Empire State Building has its own charms -- but it doesn't sing to us as the Chrysler Building does.

The Chrysler Building, on Lexington Avenue at 42nd Street, was completed in the spring of 1930, but the most significant triumph in its construction had occurred several months before. The building was originally commissioned by developer William J. Reynolds, who hired William Van Alen as his architect. New York was caught up in a rush to put up the world's tallest building, although several potential record-breaking skyscrapers that were in the planning stages never panned out. The Chrysler Corporation took the project over from Reynolds; the company's chairman, Walter P. Chrysler, wanted the prestige of claiming credit for the world's tallest building. Chrysler didn't demand drastic changes to Van Alen's original design, but the building's most significant embellishments came about as the result of Chrysler's involvement -- most notably the famous hood-ornament eagles, whose sleek heads extend majestically from eight corner points at the building's 61st floor.

As it turned out, Van Alen found himself in competition with his former partner, H. Craig Severance, who was building what he claimed would be the world's tallest building, the Bank of Manhattan, at 40 Wall Street. In the fall of 1929, word came to Van Alen that Severance had added a flagpole to the top of his edifice that would beat out Van Alen's project by 2 feet. Not to be outdone, Van Alen hatched a secret plan. In November 1929, over a period of just 90 minutes, a crew of construction workers assembled and erected the Chrysler Building's 180-foot spire, which had previously been constructed in parts, secretly, inside the building. With the addition of that spire, the Chrysler Building stretched 1,046 feet into the air, leaving Severance's building not in the dust but at least a few feet lower in the clouds, and surpassing even the Eiffel Tower's 1,024 feet. For a few months, until the completion of the Empire State Building, the Chrysler Building held the honor of being the tallest building in the world.

At the time, though, that wasn't as much of an honor as you might think. As all new constructions do, the Chrysler Building fell under the close scrutiny of critics. It was viewed as a folly, a vanity project. The architecture critic Kenneth Murchison called Van Alen "the Ziegfeld of his profession," and while Murchison may have meant it as a compliment, there were plenty of others who thought of Van Alen as little more than a flashy showman. What's more, after the stock market crash, the skyscrapers of the '20s were seen as showy and somewhat unpleasant reminders of more prosperous times.

But that's only one way of looking at it. You could also look at Van Alen's erection of that spire in November 1929, less than a month after the stock market took its horrifying plummet, as a brashly hopeful gesture.

Looking at the Chrysler Building now, though, it's hard to argue against its stylish ebullience, or its special brand of sophisticated cheerfulness. It has often been noted that the building's design was influenced by German expressionism, and it does look like something out of Fritz Lang's "Metropolis." But the Chrysler Building isn't nearly dour enough to have been dreamed up by a true German expressionist. Particularly at night, the crown's triangular windows -- lit up, fanned out and stacked high into the sky -- suggest a sense of movement that has more in common with dance than with architecture: Those rows of windows are as joyous and seductive as a chorus line of Jazz Age cuties, a bit of sexy night life rising up boldly from an otherwise businesslike skyline.

But while we're on the subject of art deco beauties, whether they're girls or buildings, we need to talk about the more disappointing qualities of the Chrysler Building. It may be true that all interesting architecture begins on the second floor, but you have to look up quite a few more stories than that before the Chrysler Building gets cooking. It belongs to the sky, not the street. The spire, the cowl and crown, the eagle gargoyles at the 61st story, are all made of what, in 1929, must have looked like the material of the future, a type of German-made stainless steel called Nirosta.

But you can walk right by the Chrysler Building and, discounting its imposing, space-age, cathedral-like main entrance on Lexington Avenue, easily mistake it for any other garden-variety office building of its era. At street level, most of what you see is an expanse of rather common, if not unpleasant, white brick. (For deco grandeur closer to eye level, check out the Chrysler Building's neighbor across the street, the Chanin Building, whose bas-relief façade is a wide ribbon of stylized Egyptian-influenced flora.)

That's not to say the Chrysler Building doesn't hold its share of wonders inside, even if some of them are at this point, sadly, mere ghosts. The lobby is an oddly welcoming expanse of red African marble (said to have been mined 200 feet underwater): The warm russet color, veined with gray, black and cream, seems to beckon you in. A majestic mural, including a likeness of the building itself as well as scenes of construction workers (some of them real men who worked on the building), airplanes and other symbols of the modern age, stretches across the ceiling, a Sistine Chapel to honor the gods of industry and prosperity. (The mural, which had grown dark with age over the years, was recently restored by the building's current owners, TWM Real Estate and Tishman Speyer Properties.)

Unfortunately, not all of the interior's art deco opulence has been lovingly cared for -- at least not yet. In the '30s, the 66th, 67th and 68th floors of the Chrysler Building were devoted to a speakeasy known as the Cloud Club, which was appointed with lavish pink marble bathrooms and a gleaming bar of Bavarian wood. Members had their own lockers (each marked with a secret code written in hieroglyphics) so they could stash their hooch in the event of a police raid. The Cloud Club is currently not in use, and there have been reports that the current owners have gutted it and parceled its fixtures out to museums. (For some present-day pictures of the Cloud Club, as well as other historical tidbits, see Chris Damore's helpful and entertaining Chrysler Building Web site.)

Until 1945, the Chrysler Building housed an observatory on the 71st floor, featuring futuristic, slanted walls decorated with deco sun-ray graphics. (The 71st floor is currently rented out as corporate office space, although the tenant has reportedly made efforts to preserve its original flavor.) It's disappointing that the observatory is no longer in use: What would it be like to view the landscape of modern New York from a room whose decoration and design were suffused with grand dreams of that as-yet-unglimpsed future?

But then, maybe it's enough of an honor to enjoy the view from the ground. It's true that New Yorkers can be disdainful of anyone who looks up: You're marked as a tourist if you're too visibly impressed by the size and scale of the city's grandest buildings. You're also likely to hold up foot traffic, which is decidedly frowned upon.

But if you don't look up at least once in a while, you'll miss out. I love looking up at the Chrysler Building from somewhere close to its base -- to see the way its glistening silver decorations, including ornaments shaped like radiator caps, seemingly appear out of nowhere against the building's simple white expanse. And beyond those radiator caps, beyond the ready-for-flight eagles, the crown is the most glorious decoration of all. Against the newly altered New York skyline, the glow of that crown seems more hopeful than ever. Eternally poised for takeoff, the Chrysler Building is always pointed toward the future. It's a building that never looks back.

Shares