The U.S. should have gotten an early clue about how hard it would be to win the war in Afghanistan — or even to define winning — on the bright morning of Nov. 26, less than an hour after the city of Kunduz fell to the Northern Alliance. Instead of celebrating that important victory, rival Alliance factions began firing rockets and automatic rifles at each other in a fight over the spoils of war. A Northern Alliance fighter, seeing everyone in the main square start to panic at the violent chaos, made a point of shouting at me, “It’s happy shooting. They are happy. Happy.”

He said the last word in a particularly manic way, delivering it like a tennis ball aimed at my head. I told him that they didn’t look very happy, since they were, after all, shooting at each other.

Moments later, the center of Kunduz was empty of everyone except gunmen.

The fighter’s absurd statement was a valiant if unconvincing attempt to spin the factional fighting that gripped Kunduz that Monday morning, one of the first breakdowns of an embryonic Afghan civil order, and a harbinger of worse times to come. In fact, a larger-scale version of Kunduz that morning is exactly what the Bush administration and the international peacekeeping coalition are dealing with today. Since the rout of the Taliban government, there have been fierce outbreaks of violence between warlords, harassment of ethnic minorities and rampant banditry, as well as evidence that both Iran and Pakistan continue to exercise their influence in the politics of Afghanistan, which has been the world’s boxing ring for the past quarter century. Demarcated by land mines and surrounded by lunatics, Afghanistan will know stability only if the U.S. makes an aggressive and not-at-all ambivalent commitment to building it.

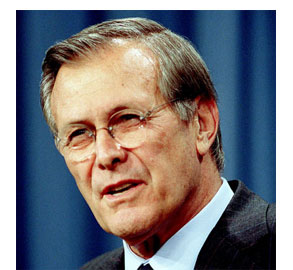

And yet the U.S. seems unwilling to make that commitment. A Feb. 20 New York Times story referenced a classified CIA report warning of further chaos and fighting between warlords if ethnic tensions are not reduced. That’s a straightforward observation, but exactly how to accomplish this task has apparently split the administration into two camps. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, articulating the Pentagon’s hands-off view, believes that the U.S. should back the creation of a national army for Afghanistan and avoid costly peacekeeping missions.

“Why put all the time and money and effort in that?” Rumsfeld said, referring to a State Department plan to increase the number of peacekeepers and extend their reach to cities beyond Kabul. “Why not put it into helping them develop a national army so that they can look out for themselves over time?”

Rumsfeld’s plan has a familiar, common-sense ring to it, like a speech given by a stern father to a no-good kid when it’s time for him to get a job. It will also lead to disaster.

Although a national army is crucial for Afghanistan’s long-term security, such an institution will be years in the making. To form a national army, after all, you need a nation, and the truth is that there isn’t enough nation yet in the inchoate chaos known as Afghanistan to develop, control or maintain an army. Afghanistan is a patchwork of tribes and ethnicities, divided and distrustful, each with their own warlord patron who claims to be the only defense against hostile forces. Major warlords control almost every large city and its surrounding provinces — Gul Aga Shirzai, a Pashtun, controls Kandahar; Ismail Khan, a Tajik, has Herat; and Abdul Rashid Dostum, an Uzbek trained by the Soviets, is the boss of Mazar-e-Sharif — and in this feudal system, each man has his own private gravitational field, a fuzzy security region that extends in direct proportion to his military influence, outside of which is lawlessness and banditry.

Here’s a snapshot of what happens when warlords cross each other in the new regime. I’d been in Kandahar only one day when my friend Amanullah Khan stopped by with interesting news. “Something’s happening,” he said. “Gul Aga Shirzai and Ismail Khan are going to war. Herat and Kandahar will start fighting soon.” Reports that fighters loyal to Ismail Khan, an ethnic Tajik, had been abusing Pashtuns had been filtering down to the Kandaharis, and they were outraged. It was Jan. 29, five days after Gul Aga had addressed a crowd of thousands in Kandahar, saying that he would wait and see what the Karzai government instructed him to do about Khan’s mistreatment of Pashtuns, saying that he preferred talking to fighting. But now everyone I spoke to was expecting bloodshed. Ismail Khan was rumored to have moved his troops south from Herat into a province controlled by Gul Aga, and in response, Gul Aga had moved his forces north and the rival factions were facing each other, ready to go at any moment. Men gathering to watch Indian television at a teahouse that evening were talking excitedly about the prospect of war.

Then, just as soon as it came up, the situation resolved itself. Frantic calls were made. Beards were stroked, and the problem suddenly vanished. What caused the almost-battle, of course, did not go away. Violent reprisals against Pashtuns were not limited to Herat. In the north near Kunduz, Uzbeks under Dostum’s control had been beating and robbing Pashtuns in the guise of disarmament, and the Kandaharis knew about that as well. Future warlord clashes are almost inevitable.

And at least a few of the warlords have powerful allies. Ismail Khan, for instance, is not just your average recalcitrant Afghan gunman; Iran is covertly supplying his men with thousands of brand-new Egyptian AK-47s, in a strategy to keep him as their proxy warlord and possibly prevent the Karzai government from unifying the country. In Afghanistan’s recent past, it is this proxy effect that has fueled ethnic tensions and kept the country in a state of perpetual civil war. When news of Iran’s military aid to Khan made its way to the United States, the State Department warned Iran to steer clear of Afghan affairs and refrain from undermining the current regime. Journalists who asked to visit the bases where Khan’s fighters were training under the guise of Iranian advisors were told bluntly to forget about it.

What does it all mean? It means the U.S./Northern Alliance victory quickly rolled Afghanistan back to a pre-Taliban boil of warlords, and the war planners are busy searching for a lid. Lately, it’s come in the form of airstrikes and special forces operations, but this is not enough to arrive at a lasting peace, only the bandit peace that war-weary Afghans have to live with for now, which will likely turn many of them into supporters of warlords, however unsavory, who can keep them safe.

What must the U.S. do? Much more than it seems prepared to. And the process may well take more than a decade — not all that long, given what the country has suffered through. First, the international security assistance force (ISAF) must grow rapidly to 100,000 troops. ISAF can, with its increased strength, branch out to cities beyond Kabul, where it has worked fairly effectively, and help restore public confidence in the civil order. In Afghanistan, the vast empty space between warlords is never secure. Most of the road separating the powers in Kabul from Gul Aga’s sphere of influence, for instance, is too dangerous to drive, but the citizens don’t have much choice if they need to travel from one city to another. (The technique is to leave early in the morning, drive as fast as possible and stop for absolutely nothing.) If ISAF took on the bandits and secured the roads, the gratitude of the Afghan people would go off the charts and the mission would gain enormous public support. The Taliban first gained credibility by ending banditry and road extortion in Kandahar province, and that was not an accident of history.

Next, and this is dangerous, the warlords must be completely disarmed, and Iran and Pakistan restrained by aggressive diplomacy. It should be obvious that leaving private armies in Afghanistan will result in civil war in a matter of months. Just as soon as the Americans and ISAF return home, the fuse will light and Afghans will re-experience the horrors of 1992-93, the worst years of the civil war. Armed principalities don’t make a nation.

The list of critical next steps seems to go on without end. Protection from famine and drought. Medicine and basic health care. Representative government. The creation of national institutions like an army. Afghanistan has a young population desperately in need of work and willing to do it. There are all manner of things to build — roads, hospitals, schools — and an organization similar to the WPA is the way to start the process. Our help rebuilding the country offers us a measure of redemption from our complicity in its destruction, going back to the war against the Soviets, and our subsequent abandonment of Afghanistan during the last decade.

The cornerstones of a peaceful Afghanistan are not so distant as they would seem, but it requires what they call in the aid business “a sustained commitment.” And there is good reason to fear that the administration, which has already eschewed nation-building as overly expensive and a general pain in the ass, will give Afghanistan a token of its affection and then simply move on to the next crisis. It doesn’t have to be that way, of course, and significant public pressure might alter the U.S. government’s posture in the region. It’s also certain that the administration’s either-or take on how to help Afghanistan — peacekeepers or the foundation of a national army — is a mistake. Peace will require both.

When I was in Afghanistan, soldiers often came up to me with the same question: Will America help us rebuild? Ashamed, I had to say that I didn’t know the answer. It should, of course, be yes. Throughout both my stays there, I saw the way Afghans treated journalists as their couriers to the West, saying to us, “Tell them that we need security, clean water. Tell them we want to live in peace.” We had to make sure to write it all down. Every request was made with a visceral longing for what we live with day after day, and we took these messages back in notebooks and tried not to forget them. It is miraculous that more Afghans are not bitter about what they have gone through, that so many look to the future with a fair measure of hope.

It seemed to me that for many of the Afghans I met, the meaning of peace transcended the absence of war. The word promised a resurrection of their civilization.

That was another message I came home deterrmined to deliver.