Whether out of laziness, fear or just plain emotional exhaustion, we're living in a time when we feel more comfortable with combat movies that are completely divorced from political ideology. We can all accept the futility and tragedy of young men who die fighting for a cause. What's harder is tangling with the idea of whether or not the cause was worthy in the first place.

That's either a relief (no more rippling flags and rugged middle-American barns in need of a paint job, ` la "Saving Private Ryan," at least for a while) or a troubling development, depending on how you look at it. Or, more specifically, depending on how a filmmaker handles it. Both Ridley Scott's "Black Hawk Down" and Randall Wallace's new "We Were Soldiers," an account of the first significant battle of the Vietnam War, allow us to join complicated conflicts already in progress -- we don't need to trouble ourselves with the how or why of them; we simply need to accept that they already exist.

Both movies take place in what critic Paul Fussell called the ideological vacuum, a place where the meaning of the initial cause has dissolved away to leave only the bloodier and much more immediate reality of young men fighting not just for their own lives but for those of the guys next to them. In his book "Wartime," Fussell quotes an American soldier who fought in World War II: "It took me darn near a whole war to figure what I was fighting for. It was the other guys. Your outfit, the guys in your company, but especially your platoon. When there might be 15 left out of 30 or more, you got an awful strong feeling about those 15 guys."

You could look at both "Black Hawk Down," which details the U.S. military's tragically failed mission in Mogadishu, Somalia, in 1993, and "We Were Soldiers" as movie-length versions of that soldier's quote. And yet the movies are hardly equal. Of the two, "We Were Soldiers" is the one with the more honorable sheen: It may be just a gloss, but at least Wallace took the time to add a few layers of it.

"We Were Soldiers" is a conventional picture in the old-Hollywood sense as opposed to the new -- in other words, action and emotion take precedence over cool effects. Wallace is more of a storyteller than a dazzler, which makes his movie at least feel more honest than Scott's; Scott dances around the issue of addressing what the hell the U.S. was doing in Somalia in the first place by distracting us with energy, movement and booming sound. (And just who are those Somalis, anyway?) Wallace does essentially the same dance, and yet it comes off as a wholly different one. There's more graciousness and feeling in it, which also, admittedly, makes it much stickier. "We Were Soldiers" isn't a great movie; I'd say it's barely a good one. But it's a war movie that at least acknowledges the distinction between macho and masculinity, always putting the dignity of the latter over the bluster of the former.

Wallace adapted the screenplay himself from Harold G. Moore and Joseph Galloway's 1992 book "We Were Soldiers Once ... and Young." Moore was the lieutenant colonel who in 1965 led the First Battalion of the Seventh Cavalry (ominously, the same regiment headed by Gen. George Armstrong Custer at Little Big Horn) in the battle of Landing Zone X-Ray in Vietnam's Ia Drang valley. Galloway (played in the movie by Barry Pepper) was a civilian reporter who covered the battle, as well as briefly taking part in it. Moore lost more than 70 men from his regiment alone at Ia Drang, and a total of more than 300 died during the Pleiku campaign of which it was a part.

In his book Moore shows no sympathy for antiwar protesters who treated the soldiers who fought in it like villains. But his views have nothing to do with flag-waving and everything to do with the men he and his fellow officers lost: "Many of our countrymen came to hate the war we fought. Those who hated it the most -- the professionally sensitive -- were not, in the end, sensitive enough to differentiate between the war and the soldiers who had been ordered to fight it. They hated us as well, and we went to ground in the crossfire, as we had learned in the jungles."

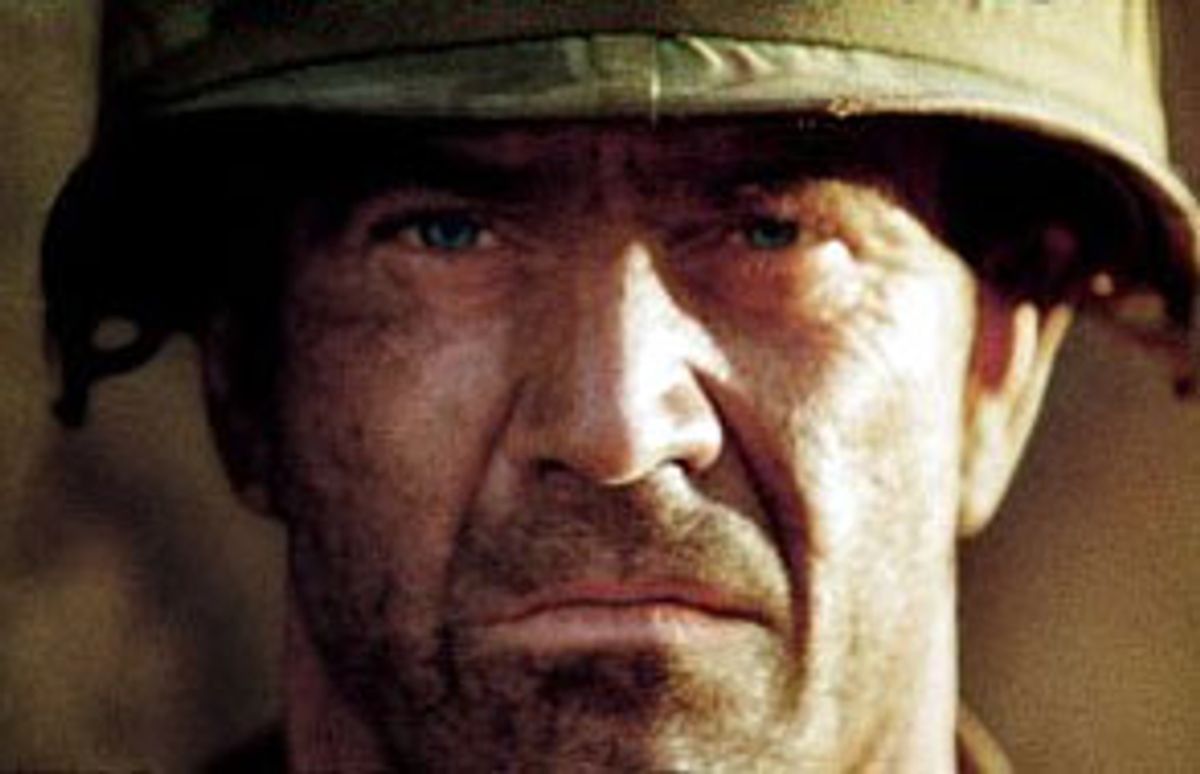

That seems to have been the significant jumping-off point for Wallace's picture, and it's not a bad one. Mel Gibson plays Moore, a devout Catholic family man with a wife, Julie (Madeleine Stowe), and five children. In the first section of the movie, set in Georgia's Fort Benning where the cavalry is training, Wallace takes some care to delineate the characters before we're confronted with the chaos of the battlefield: Sam Elliott is Sgt. Major Basil Plumley, Moore's second-in-command, whose cowboy gruffness is funny and real. (When an eager-to-please private bids him good day, he barks, "I don't care what kind of a goddamn day it is.")

Greg Kinnear is Major Bruce Crandall, the kind of chopper pilot who'll fly back into combat, against orders, to pick up wounded men. (Kinnear has disappointingly little to do in the movie, but his face shows just the right mix of good humor and gravity; if I were a wounded soldier on a battlefield, it's the kind of face I'd want to see swooping down to recover me.)

Chris Klein, an actor whose face is so openly fresh and innocent that I can almost never believe how good he is, plays Second Lieutenant Jack Geoghegan, an earnest and enthusiastic new dad. He has his finest moment when, in the Fort Benning chapel, he asks Moore about the connection between being a soldier and a father. Moore's mechanically homespun answer ("I hope that being good at one makes me better at the other") feels facile and hokey, but Klein's response to it is anything but. In that moment his face carries a look of both wonder and grave apprehension that a lesser actor could never pull off.

Wallace too often allows "We Were Soldiers" to sit in the puddle of its own melodrama, and Gibson, whose instincts should tell him otherwise, plays right into it. When Moore's lovable moppet of a daughter -- in the old days of the movie biz, you'd have called her a tot -- asks him what a war is, he stumbles through an awkwardly simplistic explanation along the lines of "Some people in another country or any country try to take the lives of other people, and it's the job of people like your daddy to go and stop them." It's a forced and highly moviefied treatment of a moment that Moore addresses much more simply, and more movingly, in his book: "I tried my best to explain, but her look of bewilderment only grew."

There are plenty of other moments that, even if they're based on real events, are dramatized in such a way that they almost throw you out of the movie. Wallace takes a tip from Philip Kaufman's "The Right Stuff" and tries to show the texture of the lives of the soldier's wives as they wait for news. But Wallace doesn't handle those scenes with the delicate forcefulness that Kaufman did: With the exception of one stunning moment by Simbi Kali Williams, they unfold like stock wartime footage of the brave womenfolk at home.

Worse yet, Wallace doesn't have a particular knack for battle sequences. They're extremely difficult to pull off: If war is chaos, how do you put it on a movie screen so it makes sense to viewers, so they always know where the opposing factions are in relation to each other? Wallace sets the scene well enough, showing us ragged swarms of Army helicopters, the military's newest and most potentially effective weaponry at the time, dipping and diving through a smoky, careworn landscape that might be beautiful under other circumstances. But for the most part, Wallace doesn't stage the fighting as clearly as he needs to; the action often feels confused and muddled, if also highly realistic.

But there are also sequences that, while they may not really work dramatically, at least suggest an underlying decency coupled with its natural and necessary twin, a sense of outrage. At one point, Gen. William Westmoreland calls Moore on the battlefield to inform him that he's going to be moved elsewhere, and Moore, battle-weary yet almost unnervingly alert, barks into the phone, "I will not leave my men!" as if he were dismissing a pesky telemarketer. (Might history have been different if more people had talked to Westmoreland that way?)

Wallace also doesn't shy away from the callousness of the U.S. government (nor did Moore, in his book): In the early days of the Vietnam War, the government sent news of soldiers' death to their families by telegram -- delivered in regular old yellow taxicabs. Wallace conveys the sense of menace those cabs came to represent for the wives at home; he shows them, glimpsed from behind the false security of cheerfully homey curtains, creeping tentatively alongside the curb like lumbering predators looking for their next victim.

"We Were Soldiers" contains one stunningly put-together sequence that takes place far from any battlefield. The soldiers leave Fort Benning for their tour of duty early in the morning, before daylight, in some cases before their families have awakened. A mere look passes between Klein's Geoghegan and his wife (Keri Russell) as they lie on their bed with their sleeping baby between them. In another house, Moore kisses Julie gently, so she barely stirs. Both men silently leave their homes, shouldering their packs and heading out on foot to the long line of inappropriately pedestrian-looking buses that will take them to their transport. Wallace shows the men in a long shot, with very little sound, gathering slowly in the still-shaky morning light, greeting one another with good humor that's all the more genuine for the way it's soaked in melancholy and apprehension.

Ostensibly, the battle sequences are the guts of Wallace's movie. But oddly enough -- and, unintentionally, to the movie's credit -- they're what you remember least when you leave the theater. "We Were Soldiers" doesn't break any new ground, and it treads some of the old ground too clumsily. But if nothing else, the sight of those men getting ready to board those pathetic-looking buses captures something of what it must have been like to leave home for a war whose aims were never clear (and, for many of us, never supportable). As Wallace shows it, those men must have felt isolation and comradeship in equal measures. Before long they'll understand that an ideological vacuum isn't a protective bubble, but a place where you have to fight to breathe.

Shares