It's October 1991, inside the brass-and-ferns Punch Line comedy club in San Francisco. The sound system is blasting Stevie Ray Vaughan at top volume. I'm here because a friend has pestered me for weeks about a comedian named Bill Hicks, whom I've never heard of. He's performed in the city several previous nights, and I've finally made it down to see a show. I'm busy editing a satirical magazine called the Nose, and writing a similar column for SF Weekly. There's funny all around me. I have plenty of friends who are cartoonists, writers, comedians. And the country is already full to bursting with comedy clubs and lame comics. So who the hell is Hicks?

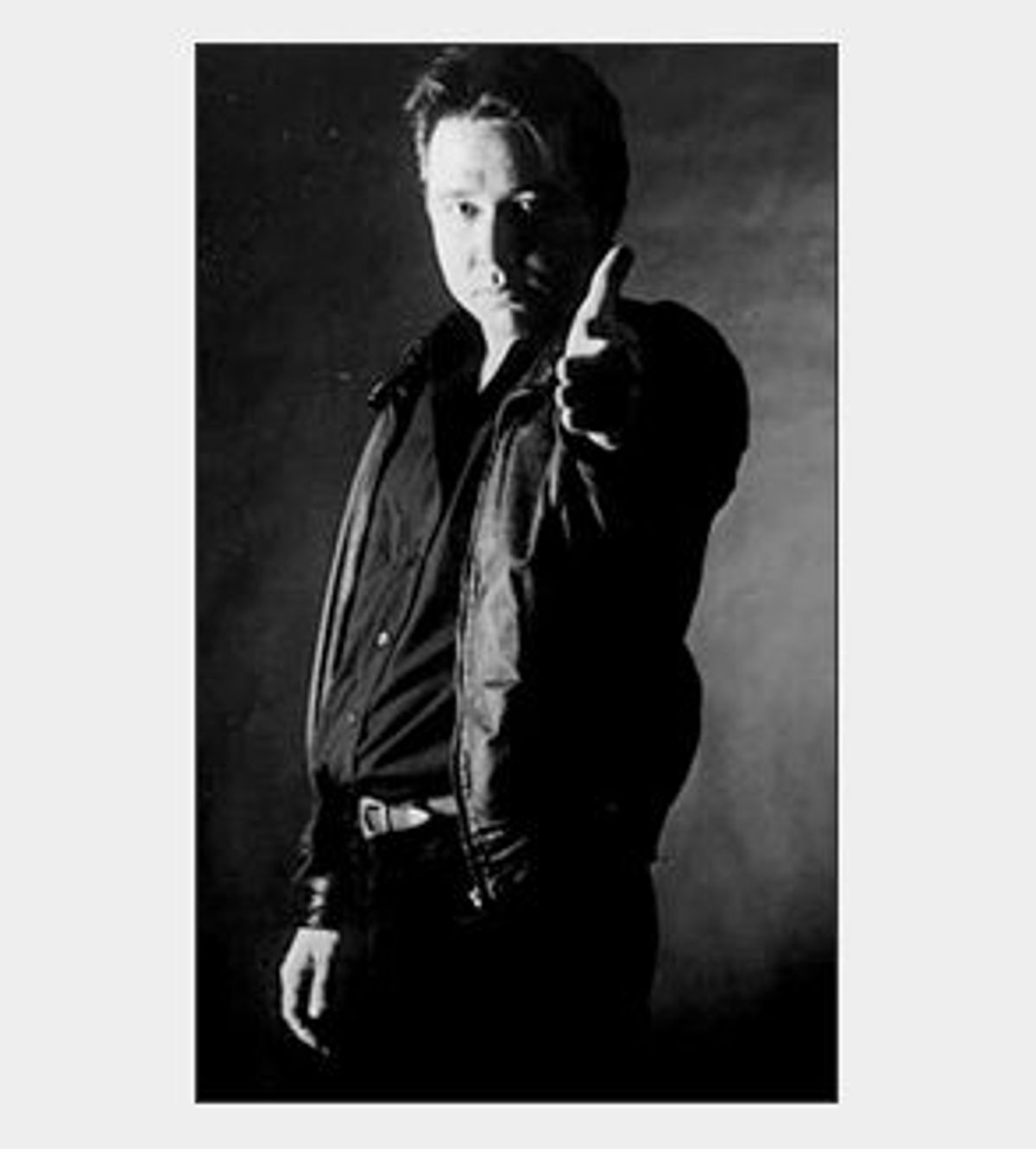

He walks onstage wearing all black, thanks the crowd, and says it's really great to be here, wherever he is. Pulling out a cigarette, he asks a guy in the front row how much he smokes. A pack and a half a day, the man answers. Hicks snorts. "You little puss -- I go through two lighters a day." He lights his cigarette, the flame adjusted to a ridiculous height, flaring like a blowtorch, and delivers a message for all the uptight, whining, prissy little nonsmokers: "Nonsmokers die ... every day." He pauses and exhales up to the ceiling. "Sleep tight."

Bill Hicks died of cancer in 1994. But here in 2002, his career is doing quite well. A greatest hits CD, "Philosophy." A brand-new Harper Collins biography, "American Scream." Bill Hicks tributes at comedy festivals in Aspen and Montreal, another tribute in London, Hollywood screenplays in the works, all of it eight years after his death. The timing is weird, but not surprising. The specter of Andy Kaufman waited 15 years for his film treatment, and 17 years for the biographies. America often overlooks its own best resources, especially in the marginalized subculture of stand-up comedy.

Back at that club in 1991, as I watched the show, I had no idea that my life was going to become intertwined with Bill Hicks, however briefly, until his death. I was preoccupied with listening to the guy, because he was astonishing -- polished, uncompromising comic sermons about hot-button subjects like Christians, JFK conspiracies, drugs, abortion. I'd never seen a comic so committed to communicating with an audience, and yet he could really care less if the crowd liked him. One bit about overpopulation ended with him squatting down to stare at the front row, and miming the act of a trailer-trash mother squeezing out unnecessary babies: "There's Trucker, Junior. There's your brother, Pizza Delivery Boy, Junior. There's your other brother, Will Work For Food, Junior," each birth punctuated with a loud "thunk." This was rude humor taken to a new level. The antithesis of TV-friendly material. No wonder I'd never heard of him.

He was an acquired taste, and the San Francisco audience got it immediately. The city has always been a town hip to comedy, from Tom Lehrer to Lenny Bruce and Robin Williams. When tourists did walk out, he'd wave goodbye and thank them for coming.

This wasn't standup comedy. It was something else: a tent revival meeting for a congregation of paranoid chain smokers? The word scalding came to mind. You felt it in your chest. I kept hearing an image, the sound of bacon frying, and thought, I need to know this guy. I introduced myself to him after the show, and he gave me his number.

I returned to the magazine offices and described to the staff what I'd seen. A black-humored, satanic Texan, holding forth on the world, articulating the doubts of every American who was paying attention. I'm pretty sure it was the first time any of us had heard Dick Clark referred to as "the anti-Christ." In some ways Hicks was expressing in a live context what we were attempting to do in the world of magazines. Except, of course, he was actually making money.

In that pre-Internet time, the Lollapalooza generation developed a perverse fascination with the dark side, from autopsy photos to vintage porn, medical oddities, tattoos, piercings and government conspiracies. America's pop culture was swirling with hellish apocalyptic information. Our magazine eagerly squeezed humor from this new shock chic. We didn't really pay attention to comedy. To us, the world was already funny and disturbing enough. But Hicks seemed to fit into this groove. We had to interview him.

I contacted his management, and starting reading his press kit: suburbs of Houston, doing comedy since age 14, part of the hard-partying Texas Outlaw comedy collective along with Sam Kinison and Ron Shock. He'd recently gotten sober, had headlined six shows at the Just for Laughs comedy festival in Montreal. He'd done Letterman, released a CD, "Dangerous," and was about to put out another. It seemed like he'd had at least two careers already, and he wasn't yet 30.

What impressed me most was that he was an autodidact redneck with a high school education, who turned around and used his background to his advantage. (In one of his bits a dimwitted waffle house waitress came up to his table, saw him reading a book, and asked, "What are you reading for?" Not "what are you reading?" as Hicks put it, but "what are you reading for?" His reply was brutally funny: "Well, I read for a lot of reasons, but one of them is so I don't end up a fucking waffle waitress.")

A few weeks later Hicks, who'd agreed to an interview, called my apartment from a hotel in Houston. As we talked about comedy and sacred cows, he tossed in things he'd read by Ray Bradbury and Kurt Vonnegut. I asked him if he ever saw himself on a network television show. He paused, and then brought up a quote from Paul Westerberg of the Replacements. The idea was essentially if you hate elevator music, by all means write elevator music.

"Like, go in there and change it," he said. "I thought that was very interesting. But I think there's so many people that hate elevator music, they're not all gonna be able to fit on the elevator. I don't know. It depends on the show. I'm totally confused about what I'm going to do with my life. That's why I'm going to an astrologer later today." He laughed.

When asked for a favorite review, he dug up a letter to a club owner from an irate woman who had attended a recent show, hoping to see some "real and refreshing humor," like Milton Berle or Sid Caesar. Instead, she listened to Hicks do bits about serial killer Henry Lee Lucas. He read the entire letter to me over the phone, shrieking with laughter at the woman's anger -- he had a great evil cackle -- and how she thought his act had no scruples or dignity. He loved such feedback; it didn't seem to bother him at all.

"You know, I don't think mass murder is funny at all," he said. "Probably the opposite. But I just have this weird theory. The best kind of comedy to me is when you make people laugh at things they've never laughed at, and also take a light into the darkened corners of people's minds, exposing them to the light. I thought the whole point of it was to make you feel un-alone. Many thoughts I do have are not my own thoughts. You know what I mean? They're not secret thoughts."

Another of his bits, he told me, was about the movie "Silence of the Lambs." The previous night, he had asked the audience if they found the film funny, a man cutting up women and wearing their skin as coats. Because he happened to think it was hysterical. The crowd oohed. Hicks described the movie's advertising, which boasted that the film was so scary, viewers will hold their seats until their knuckles are white.

"That's the way I feel after I see Chevy Chase movies," said Hicks. "I pace the floor, I can't sleep, I'm frightened. Are they makin' another 'Fletch'? How does this guy do it -- is it a pact with the devil? Every one of his movies sucks. And then I go, 'Maybe they should, you know, skin Chevy Chase and put his skin on a funny person.'"

We published the interview in early 1992, and ran cover type which announced: "Bill Hicks: Texas Outlaw Comic Says 'Skin Chevy Chase!'" Hicks returned to San Francisco, and after the show I handed him the issue, pointed to the cover type, and he busted up laughing.

Many comics will put together a solid set of jokes, and then trot out the same bits over and over again, changing words here and there. But Hicks constantly wrote more material. The quality progressed as well. No more images of kiddie-pop stars Tiffany and Debbie Gibson spanking each other's bottoms ("Now there's a video I'll watch"). His attention was shifting to the rest of the world -- the Rodney King beating, President Bush and the Gulf War, America's bully foreign policy and insights gleaned from his tours of Australia and the U.K. He asked for everyone in the audience who worked in marketing or advertising to kill themselves: "Suck a tailpipe. Hang yourself. Borrow a pistol from an NRA buddy. Rid the world of your evil fucking presence. OK, back to the show. You know what bugs me though, is that everyone here who's in marketing is thinking the same thing, 'Oh cool, Bill's going for that anti-marketing dollar. That's a huge market.'"

After the shows we'd chat a bit, but each visit he was attracting more and more people, crowding around him, that unmistakable momentum of someone on the rise. I called up my friend John Magnuson.

Magnuson was in his 60s, a film and advertising producer, and had worked with Lenny Bruce. Their 1965 collaboration, "The Lenny Bruce Performance Film," was shot in one take in a San Francisco nightclub, an unedited record of Bruce's act made expressly as a document, to be submitted as evidence in Bruce's ongoing obscenity trials. Magnuson had told me stories about the two of them planning the project, walking the North Beach streets until the sun rose, talking like maniacs. The final film ended up a legendary piece of history, serving as a record of Bruce's last-ever club gig and playing a pivotal role in clearing his name after his death.

Magnuson was always interested in the current state of comedy and satire. Hicks sounded right up his alley. If anyone could appreciate a scathing comedian who challenged the status quo, it had to be Magnuson. I suggested he check out a Hicks show, but he was skeptical. I guess I wasn't the first to recommend a new comedian to him over the years.

In the summer of 1993, Magnuson caught Hicks' show at Cobb's Comedy Club in San Francisco, and had a peculiar feeling. Afterwards he walked up and introduced himself, as he had done with Lenny Bruce 30 years earlier. Magnuson told him he'd never seen anybody that had reminded him so much of Bruce. Hicks was surprised, and very flattered. The two met up the next day, and drove around the city, shooting scenes for a ninja film spoof that Hicks had been working on.

Later that week, Cobb's was packed. After Austin and Chicago, San Francisco was Hicks' biggest market. Local radio appearances, and a positive review from the Chronicle newspaper were drawing in the curious. But there was something else in the room, a conscious efficiency, as if there wasn't time to waste. Microphones had been mounted in the ceiling of the club, recording the shows as audio sketches for a new album, "Rant in E Minor" (the final taping was eventually done in Austin).

The "Rant" album opens up with Hicks saying hello to the crowd, and immediately going off on the stunted intellectual behavior of Americans, about how the nation operates on an eighth grade mentality. A woman in the crowd shook her head no, and Hicks took the opportunity:

"Please don't debate me, it's my one true talent. I have 23 hours to develop this web of conspiracy theory, so please, just relax and enjoy your hair ... Your little cracker spawn are back at the hotel choking down the mini bar contents, probably fucking each other and producing more little crackers to come fuck with my life, you inbred redneck hillbilly fucking tourist, you. Good evening, how are you tonight? Welcome, welcome to 'No Sympathy Night.' Welcome to 'You're Wrong Night.'"

This new material was his darkest yet. He was furious over how the government handled the David Koresh/Branch Davidian episode, and kept repeating that Janet Reno and Bill Clinton were liars and murderers. "I fucking hate patriotism," he spat. "It's a round world last time I checked."

Hypocritical right-wing Christians were always prominent targets, but now the tone was even more poetically cruel. He envisioned the day when Sen. Jesse Helms finally snapped and committed suicide. Afterwards, authorities would find the skins of young children hanging in his attic, and we'd see his wife on CNN, saying, "I always wondered about Jesse's collection of little shoes."

This phase was some of his best writing, crafted for the hair-raising joy of live performance. His impersonation of a sell-out Jay Leno was devastating. But it bugged me that he kept insulting the audience. If we didn't react properly to something he said, he'd call us a bunch of sleepy cows, following each other blindly, and do a quick impression of a lazy cow chewing its cud. I remember sitting in the audience and thinking, Who are you calling a cow? I came here to see you because I'm not a cow.

When the show ended, I asked the manager if I could speak to Bill. He burst out of the backstage room and came over to where I was sitting, very focused, intense but friendly. We talked about his change in management, and his newest album-in-progress, "Arizona Bay." He thanked me for introducing him to Magnuson, and said he was looking forward to working with him. Over his shoulder I spied the tape recorder.

Hicks had always been obsessed with recording his work. Leaving a legacy was very important to him. But there was another reason for taping all the shows. A month earlier, doctors had diagnosed him with pancreatic cancer. It had already spread to his liver. In most cases, it was quick and fatal. At this point he hadn't told even close friends. That was the last time I saw him.

In the coming weeks, Magnuson talked to Hicks frequently, and kept me updated. Publishers offered book deals. The Nation invited him to contribute. He envisioned a live performance film of his "Rant in E Minor" material, shot in San Francisco, filmed in black and white. Hicks called Magnuson and asked him to do the film. Magnuson was amazed. First he got to work with Lenny Bruce, and now Hicks. As the two discussed the project, Hicks didn't seem at all to Magnuson like the kind of guy who had been told he was going to die.

In October, Hicks was scheduled to be a guest on Letterman, his 12th appearance. I was feeling out of the loop, juggling a magazine and a column, and made it a point to stay home to watch. This was Letterman's new CBS persona, tassle-loafered and double-breasted, no more sweaters and Adidas sneakers. He introduced Hicks at the top of the show, guests came on, I saw another comedian I'd never heard of, and then the program ended. I thought, was I drunk? What happened? Hicks' entire segment had been cut at the last minute.

The censorship made national news, and ended up the centerpiece of a New Yorker profile by John Lahr. In the article, Lahr referred to a letter Hicks had written to him, a 40-page explanation of the Letterman circumstances and a script of the jokes in question. Hicks also sent a copy to Magnuson, who passed a version to me. It's an impressive and heartfelt document, a first draft written longhand. The Letterman staff, especially producer Robert Morton, come off as complete hypocrites, first approving Hicks' material, then deciding at the last minute to scrap the entire segment, and blaming it on the network. Hicks admitted to Lahr that because of the Letterman incident, his awareness of the industry had changed: "I began working quite young, writing, growing, maturing, always striving to top myself -- to make people laugh hard at things they know and believe deep in their hearts to be true," he wrote. "It has been a long road, let me tell you, but after sixteen years of constant performing up until this little incident on October 1, 1993, the cold realization finally struck me. A sobering answer to the wish of that young boy I once was back in Houston, Texas, all excited with the idea that 'if they like these guys, then they're going to love me.' The realization was -- they don't want me, nor my kind. Just look at 90 percent of television programming. Banal, puerile, trite scat. And this is what they want, for they hold the masses -- the herd -- in such contempt."

With the ensuing media coverage, people were finally talking about Hicks. Because I'd written about him, I answered my share of "so what's he like?" questions. One day Magnuson invited me over to his apartment, and we watched the "Revelations" TV special Hicks had shot in London the year before, taped at the 2,000-seat Dominion Theatre. Hicks was introduced with loud Jimi Hendrix music, and walked onstage through a circle of flames, wearing a black, floor-length duster coat and cowboy hat. I thought the opening was cheesy, the cliché Wild West theme, with coyotes howling in the background, but Hicks immediately took off the hat and coat, and did his material. The Brits ate it up, the naughty American making jokes about the "United States of Advertising." Bits that had gotten a cool reception in a U.S. comedy club were understood in the nation that invented wit. Maybe this was Hicks' destiny, the direction he was heading -- a rock and roll theater act, with a smart audience instead of drunk tourists at a club.

Toward the end of the year, Hicks' management sent me another package of materials. A press release described projects in the works. Besides the book and magazine offers, he was nominated for an American Comedy Award. HBO was planning to air the "Revelations" show. Channel 4 in the U.K. had signed him to do a new program. The package also included a home videotape of Hicks performing at Igby's, a Los Angeles club, in November 1993.

This would be one of his last-ever performances, and it was a memorable one -- onstage for over an hour, a cavalcade of what he called the "comedy of hate." The audience was with him all the way, cheering even through a perverse scenario of Rush Limbaugh lying in a bathtub, with Reagan and Bush peeing on him, and Barbara Bush defecating into his mouth. At the end of the show, Hicks played Rage Against the Machine, singing along with the chorus, "Fuck you, I won't do what you tell me!"

I've screened this video to friends over the years, and the reaction is chilling. Comedians in particular stare at the screen like they've seen a ghost. It isn't the Bill Hicks they remembered, performed with, opened up for, introduced to the stage. No trademark black shirt and jeans. He was frighteningly skinny, wore a patchy beard, tweed sport coat and saggy khakis. Three months away from dying, and he was going for it, still in the saddle, riding the horse all the way down. The performance was sharp as a tack.

Magnuson and Hicks had agreed to shoot their film Jan. 23 during a performance at San Francisco's Punch Line. The date crept closer. Magnuson still hadn't heard from Hicks. The upcoming week of shows was suddenly canceled due to Hicks' stomach flu. Hicks called up Magnuson and told him they'd have to wait. I was faxed a press release alerting everyone that Hicks was "seriously ill."

January morphed into February. Hicks put all commitments on hold and moved back home to stay with his parents in Little Rock, Ark. Magnuson befriended Hicks' parents, and passed me their address. In a daze, I wrote Hick a final letter while sitting on a train, one of those dopey letters you write to someone who has inspired you. I thanked him for furthering the cause of enlightened rednecks everywhere, and slipped a photo of JFK's head autopsy into the envelope. He died a few days later, on Feb. 26. His manager Colleen McGarr and I ended up on the phone, and she started sobbing. A great one was taken from us much too early. A memorial service in Little Rock attracted comedians from around the country.

Bill Hicks passed away with a TV deal in the works, a finished film script and two albums waiting to be released. It would take his estate another three years to put out the material that was already recorded and compiled. Magnuson told me he made Mary Hicks, Bill's mother, promise not to edit any of the original recordings. And so in 1997, when Ryko released its 4-CD set, "Dangerous, Relentless, Arizona Bay, and Rant in E Minor," he noted that Mrs. Hicks had kept her word.

Joining these original CDs as part of the Hicks legacy is a greatest-hits compilation, "Philosophy," released late last year, and the new biography, "American Scream," by Cynthia True. For someone who never saw or met Hicks, True has done a thorough job of examining his life and career. She wisely stays out of the way, and lets the chronology unfold through quotes and dates, without analysis. Hicks fans will appreciate the attention to personal details, and since another biography doesn't seem imminent, this book is, for the moment, the sole full-length version.

What strikes me about her book is the differences in how it was marketed to the U.S. and the U.K. Hicks was perceived quite differently by the two nations -- in the U.K. he was stopped on the streets for his autograph, and yet in his home country he was censored off television. The American cover is a photo of Hicks sitting in a chair, in front of an American flag. On the U.K. cover, Hicks is lighting his cigarette from a burning American flag. The U.S. back cover runs a quote from Dennis Miller. The U.K. back cover prints an excerpt of the pro-life/Christians routine that was cut from Letterman's show. The U.S. version features a forward by Janeane Garofalo, a recognized Hollywood name, but it doesn't really introduce readers to the text. The U.K. edition carries a forward by Irish comedian/writer Sean Hughes, who describes the first time he saw Hicks take the stage at an Australian comedy festival. Hicks himself would have pointed out the differences, that the U.K. readers understand the wit and irony, and good old literal America, his home and birthplace, still needs to have everything explained very simply. And safely.

The United States thrives on "protecting" its citizens, and despite the Land of the Free hokum, if you dare to speak your mind and have more than 10 people ever hear it, you'll encounter offers of compromise. You'll hear unqualified taste-makers in every industry say the same things: Where can we fit you into what we're doing? No, no, no, we don't care what you think or how you feel. Can you do what this other guy did, only slightly different? How about a combination of x and y? Can you tone this down, beef this up? Can you be edgy? (A magazine editor once told me to make an article sound "undergroundy.")

And if we pretend to embrace our job so we'll always have a job, it's fairly easy to pretend to embrace the rest of the nation, right? Even if it's ironic. Once you place yourself in that proper frame of mind, it's a snap to live in America and get excited, even if it's cheap irony, over the daily distractions of unnecessary celebrities, unnecessary TV shows, unnecessary "news you can use," unnecessary electronic gizmos, unnecessarily large vehicles and the rest of the shit culture we gleefully produce, consume and export around the world. You tell me where Hicks would fit into this picture. I'd like to go there. I'd like to live there.

Among Hicks' favorite targets was the empty-headed celebrity, whether it was George Michael, Debbie Gibson, Michael Bolton or country singer Billy Ray Cyrus. One of the bits censored by Letterman was a new television show Hicks would host, called "Let's Hunt and Kill Billy Ray Cyrus":

"I think it's fairly self-explanatory," Hicks said. "Each week we let the Hounds of Hell loose and chase that jarhead, no-talent, cracker idiot all over the globe 'till I finally catch that fruity little ponytail of his, pull him to his Chippendale's knees, put a shotgun in his mouth -- POW!"

To help them run the estate, Bill Hicks' mother and father have hired an attorney from Nashville, who counts among his clients ... Billy Ray Cyrus.

Shares