Where have all the flowers gone? Gone to head shots everywhere. When will they ever learn?

But then, would we want them to? Has our appetite for starlets ever abated, even for a minute? Pinups and nudie shots from the '30s, '40s and '50s, gathered in calendars and art books, have become staples of ironically appreciated kitsch, icons for pop-culture hipsters.

No hip irony has yet attached itself to the contemporary equivalents, those two-page portraits of some up-and-comer in Vanity Fair or Esquire, shot not by some sleazy photographer operating out of a seedy Spanish-style apartment in L.A., but by the likes of Herb Ritts or Patrick Demarchelier. These girls (and sometimes guys), the layouts say, are about to be news -- or what passes for it -- and you are here at the birth of a star. The starlet shots that are the raison d'être of Maxim, Stuff or Gear don't even pretend that significance. Sometimes the models are known, sometimes they aren't. Nobody at the lads mags are seriously claiming that good work or even stardom awaits these girls; they're promising just enough barely concealed tits and ass to make readers hope there's more to be glimpsed inside.

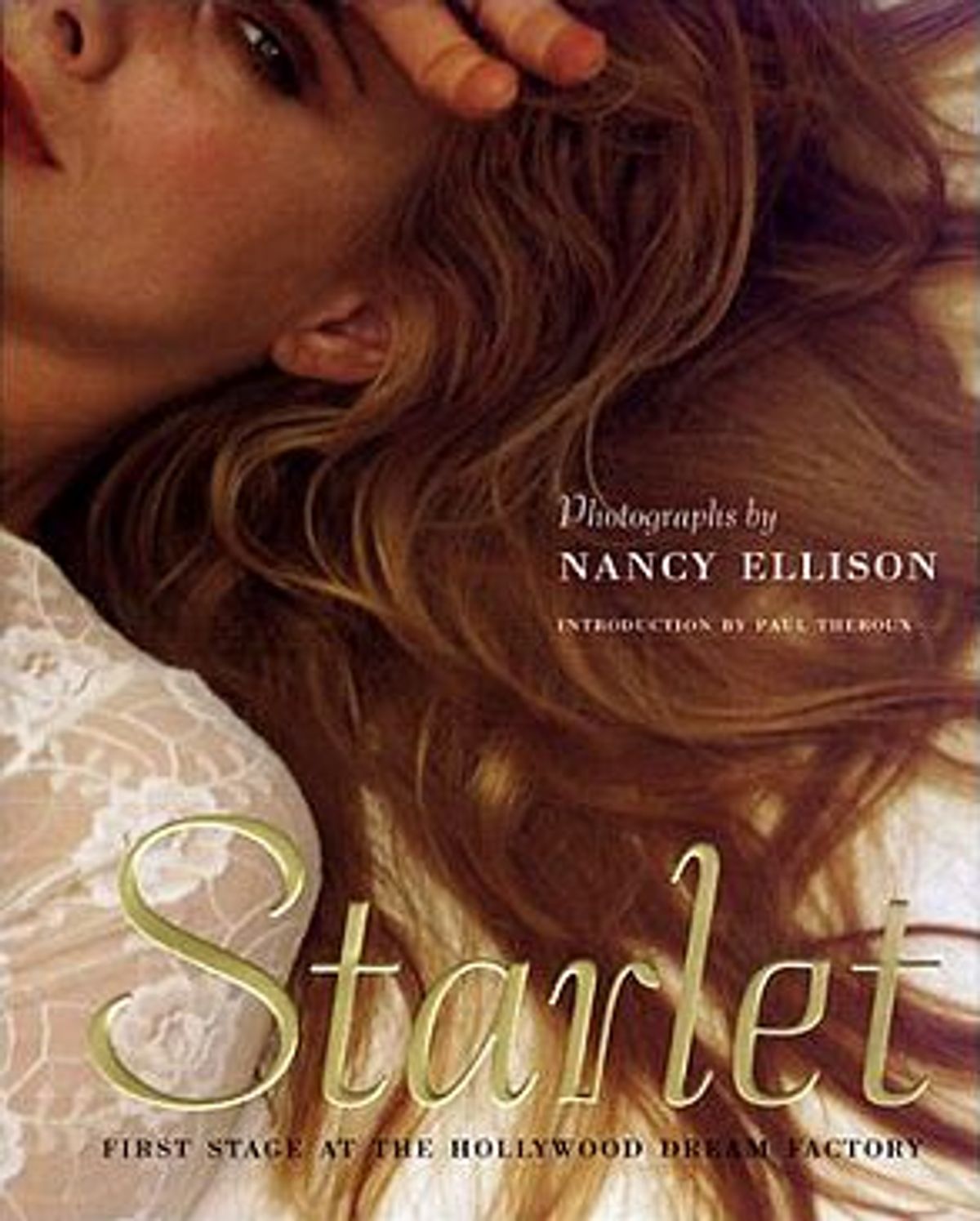

No claims for future greatness are to be found anywhere in the photos that make up Nancy Ellison's "Starlet." Ellison specializes in photos of would-be stars on the rise, the type of shots, she writes, that were once crafted by the studio publicity departments. These photos, taken from the mid-'70s to the early '90s, are removed enough from today that, by now, the subjects have either made it or faded back into obscurity -- sometimes made it and thenfaded back.

"Starlet" doesn't offer anything as homey as a "Before They Were Famous" layout in People, or home movies dug up for an E! Entertainment profile or a Barbara Walters special. In those contexts, the humble origins of stars are presented as cute diversions; we can relax and enjoy George Clooney in the car he drove cross-country, or Cameron Diaz's high-school yearbook photo, because we know they survived.

Some of the women included in "Starlet" have survived; others, God knows where they are. Sex objects fall into predictable fantasy roles. Ellison lists some of them in her introduction: "the virgin dreamer, the Loralie Eve, the bored sex object; the girl next door who might let you touch; the sun goddess, the bimbo, the harem siren, the mistress, the hippie, free lover, the brassy secretary." These photos conjure up their own fantasies: the star in chrysalis; the flash in the pan; the has-been; the oddity; and, inevitably, the victim. The young women in "Starlet" are poised to become Marilyn Monroe, or perhaps the Black Dahlia, Betty Elms or Diane Selwyn.

And yet that's an easy bit of moralizing. Of course stardom is brutal, and it's only rational to say that behind the photos in "Starlet" are stories of humiliation and indignities. But to see the women in the book only as potential victims is to fall into the prudish voyeurism fed by phrases like "the Hollywood Dream Factory," a phrase that promises truth and delivers melodramatic mystique. It's to turn into a finger-wagging hick, warning that heartbreak and disgrace await anyone who ventures to that wicked city; it's to become Piper Laurie as Carrie's crazy Bible-ridden mother looking at her daughter's prom dress and saying, shocked, "I can see your dirty pillows."

Americans harbor enough vestiges of puritanism to think that expecting the worst is equivalent to being sensible. But as Jacqueline Susann once said, there are plenty of girls who went astray without the help of books or movies -- just Uncle Clem and the hayloft. After all, we never look at photos of male starlets and feel the same kind of disapproval or moral superiority. It's likely that River Phoenix, included in a brief section here on male starlets, lived a hell none of the women in the book did. Without pretending that everyone in "Starlet" landed on their feet, it's important to remember that the scold looks at "glamour" photos and makes the subjects over in a different sort of fantasy object: the lamb gone astray who'll serve as a warning to us all.

Knowing the careers many of the women in "Starlet" have gone on to puts the images they adopt in these shots into a kind of relief. Look at "Dynasty"-era Heather Locklear in a honey-blond modified Farrah flip, smiling coquettishly in a puffy-sleeved white-lace peasant dress showing a lot of leg and shoulder. She's the quintessential prettiest girl in high school, too sunny and nice to seem really sexual. But just like those girls, she has confidence in that smile. It might be the protection conferred by all-American beauty, the Glory Days glow that will give way to settled middle-class comfort of husband, kids, nice suburban house. Who could have known that the confidence of that smile was the mark of a shrewder mind than "Dynasty" allowed, the hell-raising parodist of "Melrose Place," the crack comic displayed on "Spin City" or the "Saturday Night Live" host with the manic gleam in her eye? (Her portrayal of an infomercial hostess spouting racist garbage while never losing her June Cleaver cheeriness remains one of the farthest-out comic bits I've ever seen.)

For others, there's a kind of regret that has nothing to do with the pictures. Looking at Lesley Ann Warren sitting up in bed swathed in a fluffy pink robe can make you rueful that she hasn't had the career she deserved, has had only the intermittent chance (usually provided by Alan Rudolph, who directed her in "Songwriter" and "Choose Me") to show what a sensational actress she is.

And Sharon Stone, as always, makes you wonder what went wrong. Movies are a place to get away from virtue and respectability. That's why, as moviegoers, we've always taken more pleasure in villains and bad girls than we do in upright heroes and truehearts (who would you rather watch: Scarlett or Melanie?). Was it bad choices or bad luck that kept Stone from ruling Hollywood after "Basic Instinct"?

There's a certain amusement to be had in "Starlet" at the photos that contradict later personas or confirm them. It's fun to see Catherine Hicks, the preacher's wife on that WB virtue-fest "7th Heaven," smiling behind a white top hat, a tantalizing expanse of leg encased in white fishnets. (They're an unconscious link to the seminude layout that Jessica Biel, the actress who plays her daughter, did for Gear in an attempt to get out of her contract with Aaron Spelling.) The amusement to be had in the photos of the French actress Arielle Dombasle, best known here for her role in Eric Rohmer's "Pauline at the Beach," is a little more complicated. Rohmer, an art-house favorite and longtime critical darling, makes precise, talky, "civilized" pictures (some of them charming entertainments, and a couple, like "Summer" and "My Night at Maud's," masterpieces). But though his movies are filled with the most beautiful young women, no one ever remarks that, with his obvious eye for young female flesh, he's the Roger Vadim of the art house. Looking at Dombasle topless in red, white and blue bikini bottom, or stretched out on a couch, her pert little rump even more alert than she is, you feel that Nancy Ellison is living out Eric Rohmer's fantasies, taking the pictures he's too fastidious to take.

"Starlet" reminds us of why these photos are so tantalizing and so misleading. There are shots here, of Janet Jones and Kathryn Harrold, for instance, that are more intriguing than those women have ever been on-screen. On the other hand, there are some that capture the subject's essence. Ellison's shots of Rosanna Arquette (taken before, to use Greil Marcus' phrase, "the black hole of 'Desperately Seeking Susan,' " that numbskull movie that effectively ended her career) all contain the sexuality that not only defined her best early performances but also made her the object of desire of countless young men (I was one of them). Yes, they feature her lovely breasts and her wide, generous mouth, but also something more intangible: It's too simple to say that she was sexy because she seemed "natural," a little closer to the mark to say she was naturally sexy. Her self-presentation was too unself-conscious to seem like a pose. In other words, you looked at Rosanna Arquette and believed that what you saw was what you'd get.

The single sexiest shot in "Starlet" belongs to Arquette. She's standing in a doorway, wearing a wide-brimmed hat, tan suede cowboy boots (always hot), a denim jacket open to reveal the curves of her breasts, and a pair of skimpy white panties around which peek little curls of pubic hair. You'd never see that today, when shaved pubic regions have become de rigueur among models, actresses and porn stars. Which is not to say that the photo is sexy because of some retro-hippie rebellion against the illusion of glamour shots. Those bits of pubic hair are the essence of Arquette's unself-conscious sexuality, of the way her sexuality never seemed like a thing apart from the rest of her.

For all the glimpses of known faces, it's the pictures of the ones that didn't become stars that make "Starlet" most intriguing -- not just the mystery of what happened to them, but the unplumbed mysteries of the personalities suggested by their shots. Was there a sexy comedienne waiting to be revealed in the dewy, Marilyn-manqué Linda Kerridge? Could Leilani Sarelle (who plays Sharon Stone's girlfriend Roxy in "Basic Instinct"), with her wised-up eyes, the sort of eyes that look bruised and defiant, have become the new Dorothy Malone -- the bad-girl actress she most resembles? And what about the ones whose names even Ellison doesn't remember? The ones listed as "Unknown"?

For me, the first picture in the book, appearing opposite the title page, is the most resonant. Maybe because when it was taken, 1973, I was coming into my own adolescent sexuality, and it calls up memories of the pictures I looked at surreptitiously in Playboy or Esquire, pictures that held out all sorts of thrilling, then-unknown possibilities. It couldn't be more typical of its era, as typical as the Navajo tapestry hanging behind the model. The vestiges of hippiedom hang about the picture, an infatuation with the natural that, by then, was expressing itself in things like Earth shoes and macramé. It's a descendant of those Playboy concessions to student protest that showed girls in headbands flashing the peace sign.

In it, a model sits wearing a pair of jeans, the zipper undone in a teasing promise of what lies beneath. She has full, open lips, wears her hair long and wavy, and has a macramé shawl draped around her, opened to show her breasts. It looks as if she's been caught somewhat unawares; her hand is held tentatively between her breasts, as if maybe she'd been toying with the idea of touching them before she was glimpsed. It's all very come-hither, except that her expression doesn't quite match, and in some ways that's the most erotic thing of all. She's not a polished model, has none of the protection that you see even in the shots of Rosanna Arquette. So something of a real personality comes through her attempt to be sexy. (She also has a smooth, unbuffed body that now, when models have all worked out to perfection, holds all the promise of the exotic.)

The photo might be from the beginning of a session, before the subject relaxed, but a more "professional" pose wouldn't be anywhere near as sexy. The questions in the model's wide eyes, which betray a mixture of determination and uncertainty, can stand for the whole book: Is this the right thing to be doing? Where will it get me? Do I look sexy enough? It's the book's "before" picture, a glimpse of the clay Ellison worked with to shape the carefully modeled fantasy images of the following pages. And its mixture of fiction and reality conveys a deeper, more mysterious and lasting eroticism than anything else in "Starlet." Real can be the sexiest pose of all, and the questions the model appears to be asking herself give way to questions she seems to be asking those of us looking at her: How much do you want to take from me? And if I give it, will you remember my name?

Shares