Let me place my card on your tray. I lived as a celibate priest for 22 years and have now lived for 25 years as a married man. While a priest I headed the psychological panel of a multidisciplinary study of the American priesthood that was commissioned by the country’s Catholic bishops. As a psychologist I have been privileged to hear from the inside how priests live the celibate commitment that is required in the Roman Church.

With the misplaced confidence of people who think their troubles will end if they win the lottery, some say that the church’s problems in recruiting priests would end if celibacy were abolished. Celibacy is, I believe, a valid choice for mature men and women who want to give their lives and energy to a special cause, such as serving the poor or teaching the young. Only healthy persons — those who give without taking back more in return — can make such a choice, and the world is filled with dedicated priests and nuns who are models of this. Celibacy should, therefore, be made optional and should no longer be an absolute condition for becoming a priest. (On Friday the Boston Archdiocese’s official newspaper ran an editorial calling for an examination of this issue.)

The wider world does not lack for celibates. These are people so involved in their callings that they are fulfilled as they fulfill others. For many people, who give so much time to their work that they hardly recognize their own children, a secular celibacy would make sense. They could stay in their laboratories or their offices and avoid the collateral damage they do to wives and children by chronically neglecting them. Is there a story sadder than that of a grown-up who has spent all his life trying to find his father — that man, neither celibate, married nor mature, who was never really present for his children? Narcissists, for example, are a menace sexually and humanly, consuming people without a backward glance. They, rather than priests, should live lives of enforced celibacy.

When you hear good people speak honestly about their lives, whether they are priests, professors or private eyes, you are more touched by the poignancy of their accounts than appalled by the problems of their sexual experiences. You emerge, blinking into the daylight, feeling the profound truth of psychiatrist Harry Stack Sullivan’s observation that “We are much more simply human than anything else.”

All the tales, whether of men seeking to preserve or to lose their virginity, are touching for they are variations on the theme of how, despite years in cloistered monasteries or in wide-open modernity, so many struggle to understand their sexuality and to meet the expectations, whether heavenly or worldly, of being a man in serene and confident control of all the elements of sexuality.

For the most mature of men — that’s the short line over there — sexuality is often as much a puzzle as it is a test. It may be compared to a choir of voices that seems to have been organized without consultation with the person involved. Despite rehearsals it never sounds like the Mormon Tabernacle choir. There are times when the harmony is almost complete but, as in anything human, it is never perfect and stray notes and flat tones are often heard. Sometimes the choir surprises us with what they choose to sing; sometimes they refuse to sing at all.

How human, all of this concern, attested to by every rack of magazine covers, the women’s magazines trumpeting what men want and the men’s magazines explaining what women want, month after month, year after year. One feels like the French priest who, after hearing confessions in the mud and blood of World War I, told André Malraux of how like children most men were.

I have, therefore, listened with a sympathy born of the at-heart innocence of so many men who have felt every emotion of obsessive self-appraisal and self-doubt in trying to live as sexual beings. Next to sex, and perhaps related to it, only golf finds men talking so much about the game — how they play it, how they played it, how they will play it next time — except that they play it with each other and are sometimes terrified that, if they let women into the club, they will charge into the locker room and find them all naked. There is, I believe, less sin and certainly less sophistication than is supposed concerning sex in American men.

Celibacy means the unmarried state. It has been a requirement for the Roman Catholic priesthood since the 10th century, when Pope St. Gregory the Great forced it on the clergy to end the abuse of their passing on church lands to their heirs. It has always been and is still considered a discipline rather than a virtue. Chastity is a virtue and applies not just to priests but to all men as a condition of their fidelity in their marital relationship.

Celibacy as an optional choice for dedicated people must argue for itself. Its possibilities are so often dismissed, and its repeal is considered the answer to all church problems, because the traditional arguments for it are based on a corrupted image of human personality and highly questionable biblical citations.

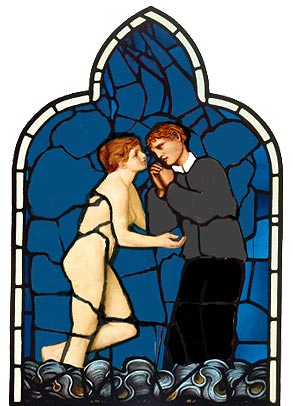

The image, as graven as any in a pagan temple, of personality as divided into antagonistic elements, has caused many good and decent people to feel guilty for being human and having sexual feelings and longings. That model, nowhere to be found in the attitudes of Jesus, explicitly says that the spirit is good and the flesh is not; that the soul is imprisoned in a betraying body, and that religion is a matter of the will rather than the imagination. It is wrong on all counts and has caused great and unnecessary suffering in a world in which there has never been a shortage of pain. A healthy attitude toward the person — not to be confused with some men’s magazine advocacy of me-first, you pick up the check, sexuality — heals the wounds that have been kept open for centuries because of the official church’s distorted perception of personality.

The scriptural and theological arguments offered to support celibacy as a spiritual ideal recommended by Jesus do not hold up under current scholarly examination. The famous quotation from Jesus, “Let him who can take it, take it,” refers not to celibacy but to his teaching a truly revolutionary doctrine about Jewish marriage. Up until that time, men had been allowed to dismiss their wives for trivial reasons, such as bad housekeeping, but Jesus condemns this, saying that they cannot marry again after discarding a wife so casually. Even a nonscholarly reading of the passage (Matthew 19: 3-13) confirms the reference (Jack Welch, among others, please take note).

How, then, do priests, forced to accept this condition, live it? In our in-depth study of priests (The Catholic Priest: Psychological Investigations, United States Catholic Conference, 1972) we learned that well-developed men observed the celibacy requirement with great fidelity. Yet these, the most mature of priests, did not live it as this sweetly singing virtue, as much as they adjusted to it as a bland circumstance of their service to their people.

How did they adjust to it? The only way that priests adjust well to celibate living is through a network of strong supportive human relationships. At that time, the culture of the priesthood provided such relationships in the high-spirited fraternity that characterized their life together in rectories. Additional research at the time revealed that almost all successful celibates also had close nonsexual relationships with women, often with one of their sisters but just as often with a member of the parish — a mother and wife, perhaps, who welcomed the priest into her family life.

Priests who were less well-developed displayed a range of maladjustments, ranging from an isolated bachelorhood to severe psychological conflicts. Celibacy, however, did not so much cause these problems as it brought them out in people who brought into seminaries their long-standing serious internal difficulties.

Celibacy, then, was clearly oversold as a virtue and underexamined as a manner of living. Since that time, and largely because of changes in the source and number of candidates for the priesthood caused by sociological upward mobility of Catholics in general, church officials have accepted men less psychologically robust to fill the empty places. These men have evinced greater problems understanding and managing their sexuality but, again, these are conflicts they brought in their baggage to the seminary. Among these has been a small but substantial number of men with poorly differentiated sexual identities. These preadolescent priests, victims first of the system that accepted them, went on to victimize in numbers almost beyond belief the children placed in their care.

Celibacy is not the cause of priestly pedophilia. It is, however, a condition and requirement that needs what the pope refuses to allow, namely an in-depth examination of the real-time, real-life celibate existence. Unexamined and falsely and fragilely celebrated as a great virtue, it has become at least the partial source of an ongoing misunderstanding and misinterpretation of human personality in which flesh and spirit, soul and body, imagination and will, are made antagonists in a long unrelieved siege. That is the wound that remains unhealed in the church, a wound that has affected not only the lives of priests but of men across cultures who are puzzled by being made to feel guilty for being human and having sexual feelings.

The dedicated celibate priest may well be able to express his generativity through giving of himself to his parishioners and their families. Still, the man capable of choosing optional celibacy for the right reasons is relatively rare. Most priests adjust to celibacy and find ways to adjust to their sexuality as well. They are very like other men in the way that they do this and they certainly are not strangers to sexual expression. While many of them are truly heroic, others feel the burdens of their state very greatly. What they miss is not so much sexual gratification as a relationship with a woman of which sexual intimacy is a rich and confirming element.

That, of course, is what every person seeks. Seeking it, they may have one-night stands and the next-morning blues — that touching symptom and side effect of America’s search for true love — and that surely reveals nothing but their humanity. So I look with great sympathy on all men and women and think that the church should do everything it can, as Pope John XXIII said, “to make the human sojourn on earth less sad.” Making celibacy optional would help, affirming the unity of the human person would help more, doing everything to support people as they search for love would be best of all.

I was happy and very busy as a celibate. I am happier and just as busy as a married man. It is not the state in itself that guarantees that but the nature of the human relationships involved. I am that lucky fellow, a happy man, who found in relationship to my wife the kind of love that can never be found in friendship. While officials in the church tried to humiliate me for choosing to leave the priesthood for marriage, I have been fortunate that whatever is healthy in me and my wife has always been stronger than what is ill in many church officials.

Sexuality is an integral part of loving someone else. Nobody is married long without realizing that nourishing the relationship in a hundred small ways is the best seasoning for sexual intimacy. Sexual relations outside tenderness and an understanding of our fundamental human imperfection will never sustain love. It is just the other way around. Perhaps it would be better to teach courses, in seminaries and grade schools, about the mysteries of friendship and love rather than sex education.

I cannot close without a special word for a group of men who deserve great understanding and great praise. These are the priests, many of them old men now, who remained courageously and dutifully in the priesthood even though they never really wanted to be priests in the first place. So powerful was the culture when they were adolescents, however, and so demanding many of their mothers that there should be a priest in the family, that they felt that they had no choice and stuck it out, serving well with a great secret sorrow.

One of them spoke to me recently of how the once dominating institution of the church forced him to accept a celibacy that, as he sees it now, “robbed my life from me.” He paused, “I feel it,” he said, “when I see children who could be my grandchildren and great grandchildren. They could have been mine, these little ones with their daddies. That is how I feel the loss.”

He sighed, this good man, worn out and worn down and filled with dreams of what might have been. It is clearly not the sex that he longs for but the family life that is beyond his reach now. “As I talk,” he said, “it may sound as if I am criticizing the church. I am an American and I can criticize it. I’m a Catholic and proud of it. Does the church really understand celibacy? I don’t think so. What I have seen is the institution’s heartlessness, the way it controls men this way. These feelings are buried in a lot of guys.”

He speaks for many priests, yes, but he speaks for American men as well. He speaks for all those who, under the shadow of the institutional church’s negative and divided view of personality, suffer unnecessarily just for being human.