The 1780s were not a pretty time to be a working-class lass in Mad King George's England. If you were lucky enough to have a job, say, as a milkmaid or a shopgirl or a laborer, you were likely to lose it to one of the 130,000 military men just returning home after a rousing defeat in America. Or perhaps you'd get booted from your job because of a new tax on maidservants over the age of 15.

Utterly abandoned by your government, you would likely end up living in a boarding house, sharing a mattress with a few other "disorderly girls" and paying for your gin and your fatty meat by shoplifting or prostitution or other petty crimes. If you were picked up by the police you'd be thrown into a crowded, typhoid-riddled jail to await one of several dismal fates including death by burning at the stake or "Transportation to Parts Beyond the Sea" -- namely, Sydney, Australia, a starving, muddy colony surrounded by tribes of Aborigines.

Sian Rees' "The Floating Brothel" chronicles the voyage of the Lady Julian, a ship that transported 237 female British convicts to Sydney, Australia, in 1789, part of the so-called "Second Fleet" (the First Fleet sailed in 1788). The women were sent off to colonize Australia for two convenient reasons. The first was to empty the jails, which, thanks to an epidemic of disorderly girls who had hit hard times, were seething pits of filth and disease. The second was so the girls could serve as brides, wombs and sexual playthings for the lonely men of Australia -- a motley collection of convicts, researchers, colonialists and marines -- who at the time outnumbered female colonists by roughly 5 to 1. It wasn't a lovely fate.

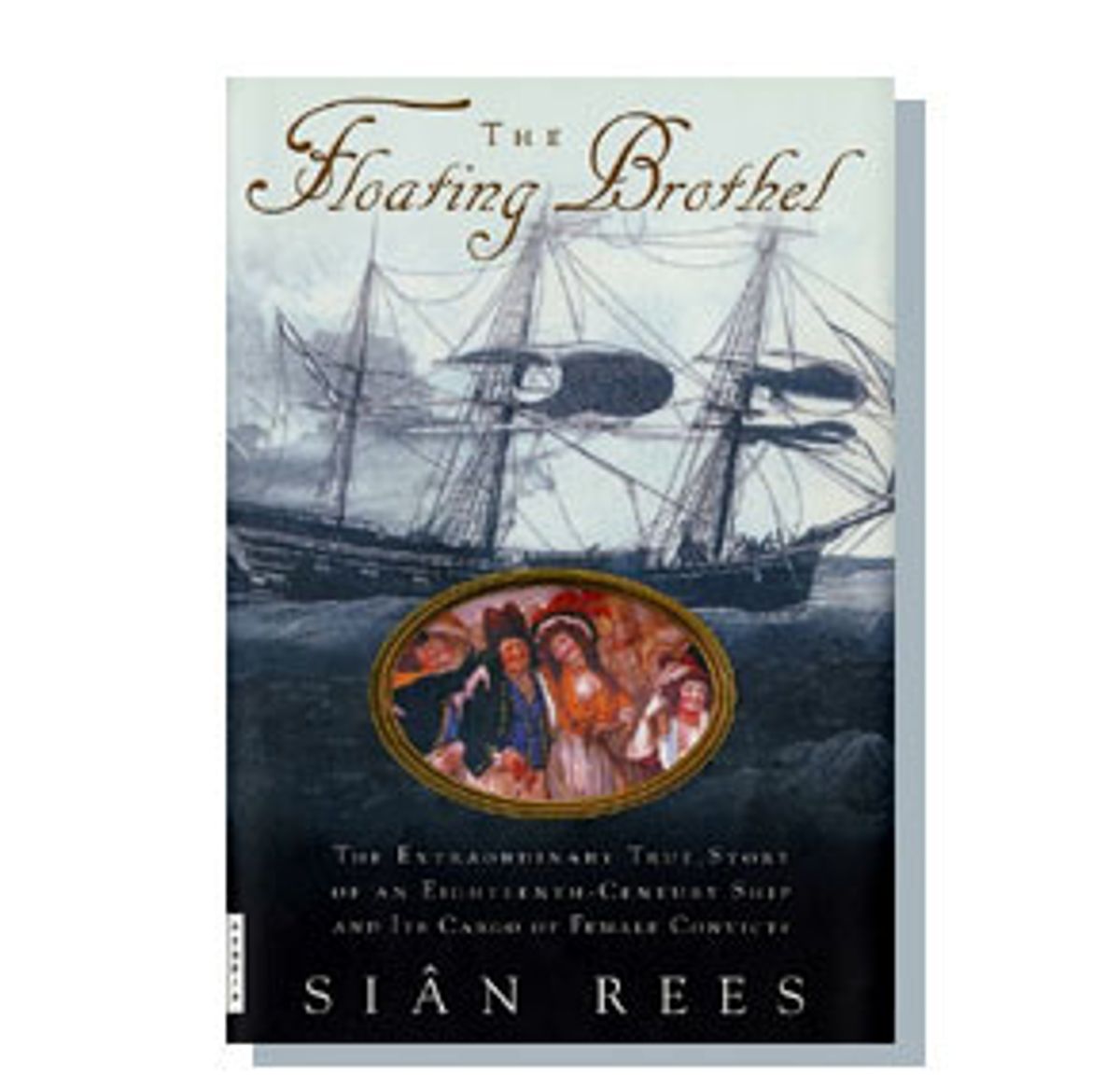

Make no mistake: "The Floating Brothel" is not a titillating tale of 18th century high-seas hanky-panky. Despite its evocative title and bawdy cover, which features a bare-breasted lass lecherously grasping a portly gentleman, "The Floating Brothel" discloses very few details about lustier aspects of sex-for-hire in the late 1700s. Rather, it is a meticulously researched historical treatise that chronicles the sexual, physical and emotional exploitation of the Lady Julian women from a lively feminist perspective.

Readers will, however, learn plenty of other fascinating facts from this period, such as the menus served to sailors of the era (salted cabbage); the symptoms of scurvy (black pustules all over the body); the nature of waste removal on ships (think "floating piles of excrement"); and the percentage of monstrously deformed babies born in the 1780s (one in every 241). Not exactly sexy stuff, but interesting just the same.

Unfortunately, there are few first-person historical accounts, such as diaries or memoirs, of the 237 women aboard the Lady Julian (hardly surprising, considering that most weren't even literate enough to sign their own names); as a result most of Rees' material was cobbled together from court and legal documents. Rees' research gold mine was the memoir of John Nicol, the Lady Julian's steward and the hapless lover of 19-year-old convict Sarah Whitelam, who was shipped off to Australia for stealing a closetful of clothes (including a "Raven Grey Conventry Gown" and "One Chocoloate [sic] Ground Silk Handkerchief").

The tale of Whitelam and Nicol is hardly a stirring love story. As it turns out, all the sailors on board the Lady Julian were promised a female mate for the trip, a common practice among ships that carried female convicts. The women who were on board, ranging in age from 11 to 68, were parceled out as temporary "wives" to the sailors for the duration of the voyage (more than 11 months). Although a few of these pairings actually bloomed into real relationships (Nicol, according to his memoirs, actually did feel real love for his bedmate), most seemed simply relationships of convenience. For the sailors, a "wife" was a convenient sexual plaything; for the convict women, the relationship was a way to escape the crowded convict holds below deck for a more comfortable bed and a bit of special treatment during the voyage.

"One can only speculate on the attitude of the women towards the men on board and whether they believed it possible to have a relationship with any man which was not principally characterized by coercion," writes Rees. She guesses that the main reason to compete for a position of sailor's mistress was protection. "Most on board had come from extreme hardship and were, necessarily, selfish and cunning ... Some must have regarded the sailors coldly as a source of extra food, extra drink, extra privileges and some safety from the stealing, cheating and bullying going on at the bottom of the ship." These women weren't, in her eyes, merely victims, but in fact were quite savvy ladder-climbers even if they were starting at the bottom rung.

Besides bedding the sailors and officers, there were ample opportunities for the women on the Lady Julian to use their bodies to their advantage along the way. The Lady Julian made several stops during the trip, in Spain, Portugal and, due to some unfortunate sailing mishaps and a shipboard bout of scurvy and pregnancy, Rio, at which point the prostitutes on board would avidly service the locals and sailors from the other ships at port. In most ports, hookers would row out to the sailors; with the Lady Julian, it was the locals that arrived at the side of the ship. Apparently, seeing the Lady Julian sail into port was an 18th century version of Heidi Fleiss showing up on the Queen Elizabeth with a boatful of hookers in Manolo Blahniks.

When the ship finally sailed into port in Australia, the women were parceled out yet again and married within days. Their grooms were famished, sex-starved and barely-alive colonists who, lacking farming and hunting skills, had been barely clinging to existence while they awaited reinforcements. Many of the women had husbands back in England, had kids in tow, or had given birth to children during the trip. No matter -- a willing female was a willing female for the colonists.

The sailors returned to the ship and the female convicts started yet another series of advantageous sexual relationships as a way to jump-start their lives in Australia. Sarah Whitelam, despite her supposed true romance with Nicol -- who had promised to return for her as soon as he could -- was married the day after he sailed off for Canton.

It's unclear who played the primary role in all these sexual shenanigans, and Rees implies that rather than "blaming prostitution on the prostitutes," perhaps the men of the ship should be fingered. Were the women sexually exploited by the sailors, or was everyone involved simply making rational choices? Were the hookers who sold themselves in the ports savvily earning some petty cash en route to their new homes in Australia -- or was the captain of the Lady Julian serving as a pimp and skimming a profit off the top of these illicit trades? And once the convicts arrived on shore, were the women smart enough to coordinate their own marriages, or was the decision-making all on the part of the men? Who was zooming who?

Unfortunately, we never really find out -- in part because Rees simply has no idea. Because there are no first-hand accounts from the women of the ship, the book is filled with speculation of what they might have thought or done. That is where the "The Floating Brothel" breaks down. Although the book is filled with delightfully colorful details about life in England and on board ships in the late 1780s, it is free of actual narrative specifics about the Lady Julian. Even Nicol's memoirs are vague and inaccurate; for example, although his "wife" gave birth to their son during the voyage, he neglects to offer any details about her pregnancy or childbirth, so Rees is forced to speculate about the pain, the birthing stool, the presence of a midwife.

Though Rees seems to want to turn her book into a kind of feminist discussion of the exploitation of these women, and often returns to the subject of the moral implications of this sex trade, this is the most tenuous part of her research. "The Floating Brothel" is more solid when she provides specific historical details: explaining, for example, that prostitutes used to insert molded bits of wax into their vaginas as a barrier to prevent pregnancy, or providing gory details about the epidemic of smallpox in Sydney, which killed scores of aborigines and left piles of bodies on the beach for the dingos to eat.

Considering how little primary material Rees had, however, she does an admirable job of piecing together the value of sex as a commodity for these impoverished, cutthroat and disadvantaged women. Sex was all they had to offer, and they used it wisely; and for those who survived the trip and matched themselves advantageously once they landed on the Sydney shores, it actually served them well. Of the 237 women shipped off to Australia, only a handful ever returned to England. The rest of the hookers and thieves became the colonial founding mothers of Australia, peopling the country with their legitimate and illegitimate spawn, and destined for a far more glorious history than they might have experienced had they stayed behind.

Shares