Moishe is a 10-year-old boy with a plan. When he becomes prime minister of Israel, he says, his first move will be to get rid of all the Arabs in Jerusalem. For now, he wishes they would just fly away.

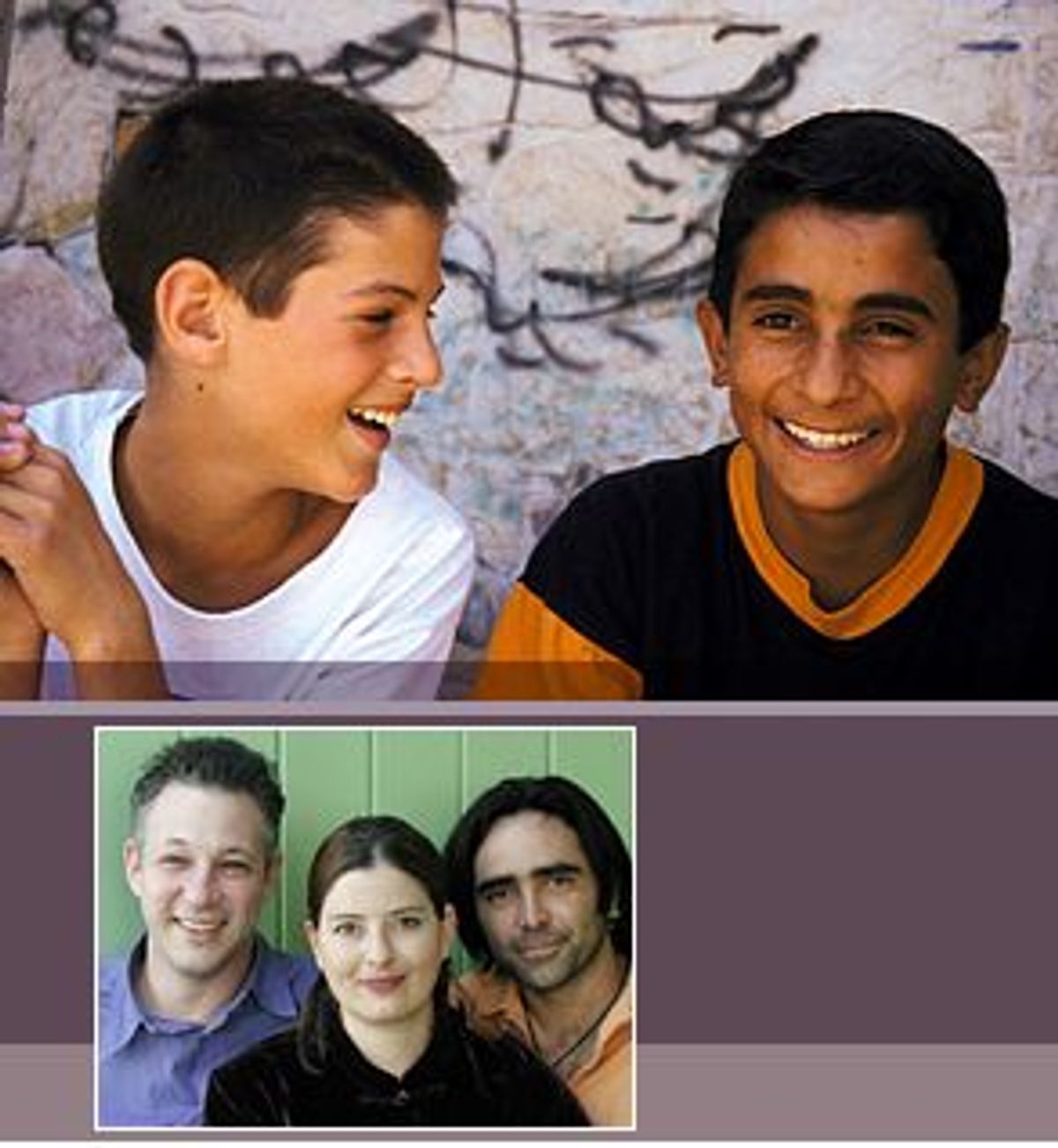

One of seven children featured in the film "Promises" -- a strong bet to win the Academy Award for best documentary on Sunday night -- Moishe has never met a Palestinian. Still, he is convinced he can't stand them. Speaking directly to the camera, in his husky, high-pitched voice, he tells us he comes from the West Bank settlement called Beit-El, "a place where people who hate Arabs live."

In the Muslim quarter of Jerusalem, blond-haired, blue-eyed Mahmoud is equally antagonistic toward Israelis. His family owns a coffee shop near the Al-Aqsa mosque, and every day Mahmoud prays for the end to Israeli occupation. Although neither boy can speak the other's language, their rhetoric is almost interchangeable.

"If the soldiers miss their aim it's OK, because they might hit an Arab," says Moishe breezily, while cycling past an Israeli firing range.

"The more Jews we kill, the fewer there will be," says Mahmoud, his baby face clenched in defiance, as he proclaims support for Hamas, the radical Palestinian militia.

In news reports from the Middle East, children usually play a symbolic role: We might see pictures of a Palestinian boy dying in his father's arms, or tiny coffins placed in Israeli graves after the latest bombing. But we rarely hear personal accounts from those growing up in the shadow of violence, where death stalks the land and innocence is often the first casualty.

"Promises" is one of a modest handful of efforts to capture a child's-eye view of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Between 1997 and 2000, filmmakers B.Z. Goldberg, Justine Shapiro and Carlos Bolado traveled into and around Jerusalem, interviewing young people between the ages of 9 and 12. Goldberg, an Israeli-born American journalist; Shapiro, the Berkeley, Calif.-bred host of the U.K. travel series "Lonely Planet"; and Bolado, a film editor from Mexico ("Like Water for Chocolate," "Amores Perros"),combined their diverse talents and perspectives for this finely crafted, deeply moving feature, which has scooped up multiple awards at festivals worldwide. ("Promises" first aired on PBS in December and is currently playing theatrical engagements in New York, Boston and Los Angeles, with other cities to follow .)

Along with Moishe and Mahmoud, "Promises" takes us into the daily lives of Sanabel, a Palestinian girl who lives in the Deheishe refugee camp and whose journalist father has spent two years without trial in an Israeli prison. Sanabel takes part in protest marches and performs traditional Palestinian dances. Faraj, also a Palestinian refugee, channels his frustration into competitive sprinting; in one especially emotional scene, the filmmakers take Faraj and his grandmother to see the land his family fled in 1948.

In Jerusalem, twins Yarko and Daniel, from a secular Jewish family, question the existence of God but still pray at the Western Wall for victory in an upcoming volleyball game. An entertaining and photogenic double act, Yarko and Daniel are more interested in school and sports than in their so-called enemies. But when they ride the school bus, their eyes dart left and right, in fear of terrorist attacks. On the other hand, Shlomo, the bookish son of an Orthodox American rabbi, says he feels safest in Jerusalem, because it is a holy city for both Jews and Muslims.

All these children are neighbors, living only minutes apart, but they live in alternate realities. There is much talk of war in "Promises," and any of these cute kids could grow up to be instigators of violence, but the film's underlying theme is an appeal for some kind of neutral ground. Of course, making a film that calls for peace in this region is itself a kind of political statement, a rejection of the extremist rhetoric in which both sides have engaged. In "Promises," the message comes across more as a prayer whispered between the lines than as a pamphlet shoved into the hands of the audience.

Director-producer Goldberg appears as confidant and mediator in the film, engaging with the children in both Hebrew and Arabic. It's a risky but ultimately rewarding move, for we warm to his presence through the way he relates to the kids. When Mahmoud spits against Jews, Goldberg reminds him that Goldberg himself is a "Jewish boy." The camera zooms in on the boy's hesitant expression, as he wrestles with his mixed feelings for the man he now calls his friend. "You're not a real Jew," Mahmoud finally insists. "You're American."

Goldberg's role is also central to the film's turning point. When he shows Yarko and Daniel a Polaroid of Faraj, the twins ask if they can meet him. Faraj is unreceptive at first, but after Sanabel's encouragement, he invites the twins to his camp. In one of the more touching moments, we see the fiercely proud Palestinian boy in front of the mirror, slicking back his hair and wearing his best shirt, to prepare for his guests. The meeting breathes hope into the film, but it's punctuated by a wrenching scene in which Faraj breaks down in tears because his new friends, including the filmmakers, will soon leave.

Even more painful is the film's epilogue, shot two years later. Sadly, most of the children remain polarized. Checkpoints have prevented Yarko and Daniel from returning to Deheishe. The fire that was burning in Faraj has been dimmed. One look into his eyes tells you everything you need to know.

Particularly in light of the region's present state of affairs, "Promises" can make for wrenching, even heartbreaking viewing. But there are surprisingly hilarious moments, largely thanks to children's natural tendency for slapstick and unwitting humor. The funniest sequence comes one afternoon when Shlomo is walking through an Arab neighborhood of Jerusalem. As if on cue, a Palestinian boy confronts him, loudly burping in his face. Shlomo continues talking to the camera, but after a couple more eruptions, the future rabbi cannot help but respond. The scene rapidly becomes a belch-off, leaving the kids and the audience giggling. Boys will be boys, after all. It's also a suggestive metaphor: How much of the political positioning on both sides of the Israeli-Palestinian divide can be reduced to hot air?

After a February benefit preview of "Promises" at a screening room in New York's Tribeca neighborhood, the filmmakers talked about their ongoing relationship with the kids and described what each is doing now. Sanabel continues to dance, Shlomo is focused on his religious studies, while the twins are still glued to their volleyballs. Mahmoud is more interested in girls than revolution, and Moishe has more fun translating Harry Potter books into Hebrew than hatching plots to banish the Arabs. Interestingly, Goldberg notes that Mahmoud and Moishe enjoy the same music: Britney Spears and 'N Sync. (Apparently, bad taste knows no boundaries.) Faraj is still despondent and dreams of emigrating to America.

A couple of days later, I sat down with B.Z. Goldberg and Justine Shapiro to discuss the kids in "Promises," the future of the Middle East and the sometimes agonizing, shoestring-budget production process through which they made this extraordinary film.

Where did you find these wonderful kids?

Goldberg: We were looking for children who represented the major forces in the conflict, children who were articulate, who liked us and who were interested in the process of filmmaking. And whose mothers cooked good. It's true, some of their mothers were incredible cooks, and as a starved, broke film crew, we found ourselves gravitating back to those houses.

Were any of the parents hesitant to get involved?

Goldberg: Once they saw that we were not in for a cheap, quick news interview, that we actually were having a relationship with their kids, and their kids trusted us, then the parents, by and large, were very open. Also, cameras are so prevalent in the Middle East, with film and video and news teams, they're just part of daily life. So it was less strange to have a camera around than it would be to make a film about a family here.

Were you really surprised that Faraj, a Palestinian boy living in a refugee camp, wanted to meet Daniel and Yarko, the Israeli twins?

Goldberg: Oh my God, we were not ready for that at all. I mean, literally in the middle of an interview, he said, "I want to call them." And that telephone conversation was edited down to a few minutes in the film, but it was close to an hour and a half long.

When Faraj started crying, and then the camera cuts to you in tears, how did you feel about that choice?

Goldberg: Carlos Bolado, our cinematographer, insisted in putting that in. I fought him because I thought it was too self-indulgent. But he convinced me that it showed something of our relationship. So it's hard to watch, it's something that in this culture is not particularly appreciated. A Russian guy walked up to me at the film festival in Berlin, and he looked me in the eyes and said [puts on accent], "I see your film in Rotterdam. This is best film I seen in years. I cry in your film." I explained to him that in America, men are macho, and no American man would tell me, "I cried in your film." That's just not something you would show off. And he said, "Russian men very macho too. But, you cry in film, so I can tell you I cry." So, that was a moment where I started to feel OK with it.

Why did you choose that particular age group?

Shapiro: It was really what kind of motivated us to make the film. For some reason we ended up meeting amazing kids at the beginning of our research in 1995. Moishe was the first one we met. He was 8 and a half years old and he was like this 50-year-old man, with his body language. I don't speak Hebrew, but I was just mesmerized by this character. What was amazing about the age group is they were so candid, so uncensored. When they parroted their elders, they would say things that I don't think their elders would have said so readily on camera. Also they weren't teenagers yet, they weren't cool, so they weren't so self-conscious. And they were still at that age where, like Faraj, he changes his mind, and you just don't see adults do that very often.

I also think it really humanized the issues, because even though you can't believe some of the outrageous things that Moishe or Mahmoud say about the other group, at the same time you're responding to this person who's just a child.

Shapiro: It's disarming to hear this stuff from kids, and the feedback we've gotten reflects that. People come to this issue with very strong opinions, and I think this film really opens hearts. Despite themselves, people end up reengaging with the conflict. A lot of Jews respond to the Palestinians very interestingly, like, I didn't know Palestinians could feel. Most Israelis don't know a Palestinian.

Goldberg: They definitely don't know them intimately.

Visually, the film is so striking. Justine, I suppose your "Lonely Planet" experience made you focus on geography and landscape?

Shapiro: One of the most exciting discoveries I made in the process of making the film was understanding the geography and what the landscape feels like. Jerusalem is the holy city, but it's also congested and poorly planned. So, you know, as long as we're humanizing these characters, let's take the veil off the city. It's not just the Al-Aqsa mosque and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, and the quaint cobbled roads of the Old City. It's also this urban nightmare.

It's amazing to see the geography, with everyone 10 minutes away from each other.

Goldberg: And they don't know each other.

Shapiro: Yeah, when the film played at the Jerusalem Film Festival, Sanabel and Faraj were a 15-minute drive away and they couldn't come to see it.

Goldberg: Maybe what's even more ludicrous is that few of the people at that screening had ever been to that area [the Palestinian refugee camps], even though it's so close. And now it's become even more difficult, in fact impossible, to go there.

What was your biggest challenge in getting this film off the ground?

Shapiro: People were really skeptical. Here were these two Jews who'd never made a film before, coming from the liberal San Francisco Bay Area. What's their agenda? A lot of conservative Jews thought that the film must have a pro-Palestinian agenda because we were liberals, and a lot of Palestinians thought we had no business making the film at all. But one South African woman that we met in 1996 saw our first fundraising clip and thought the film was really important. She donated probably a ninth of our budget, and told us, "You guys are going to win an Academy Award." It's funny, the day the nominations were announced, she was the very first person to call at 7 a.m. and congratulate us.

In terms of funding, were there times when you thought that this just wasn't going to happen?

Goldberg: Were there times when we didn't think that?

Shapiro: You know, it's funny, I'm still close to all the years of struggling to make the film. We had close to 200 hours of amazing footage, but what I didn't know was, how are we going to craft a film that will have the same qualities that make a feature film work. What's our narrative? What will the arc to the story be? How will the characters change? We really wanted the film to work as a cinematic piece, not simply as a worthy social documentary. B.Z. and I had never made a film before. We were just really interested in the subject, and in storytelling, and in the medium of film. So we involved Carlos Bolado, because we needed to work with somebody who really understood cinema. Our intention was that a mainstream audience would respond to this film. And one of the benefits of having to fundraise, and having it be such a hard, long road, is that we ended up staying with the project probably twice as long as we anticipated. It was a gift in a way, because we ended up spending much more time with the kids.

Where was "Promises" first screened?

Goldberg: It was in Rotterdam, and I was sweating bullets. Everything was in a crunch that week. I took the wet print of the film down to L.A. for the subtitles to be done. And everything went wrong at the subtitle house that day; they had just fired their general manager, the account manager had quit, one of the simulation machines was broken. There were spelling mistakes, and I didn't have time to proof. And I think they were working on the Spanish subtitles for "Tarzan" at the same time. I carried the print back up to San Francisco, and it was too late on Friday to go to the lab. Saturday everything was closed. Sunday, first thing in the morning we flew to Rotterdam with the print. So on Tuesday at the festival was the first time anybody had seen the finished film. I was convinced, in my heart of hearts, that the film was going to have the subtitles to "Tarzan" in Spanish. Once the subtitles seemed to be OK, I was then convinced that the audience was about to get up and leave. I was holding onto the chair for dear life.

Shapiro: We had no idea that the film would have such a great reception. We were rejected by Sundance and HBO also turned it down. There are not many venues for documentary film. We never expected it would have a theatrical distribution. I was putting up posters in Rotterdam, the festival was ending in two days and somebody came up to me and said, "Congratulations, your film's at the top of the audience poll." I didn't even know there was an audience poll!

B.Z. mentioned that at first he was uncomfortable being in the film.

Shapiro: B.Z.'s role in the film is sort of tricky. You know, we were all concerned that if his role weren't calculated, he would become a buffer between the audience and children. So the extra time helped us sort out these inherent issues, and persuade him that it would help the narrative work. B.Z. was so connected with the kids, it seemed really silly not to show that to the audience. I think having him talk to them directly also helped the kids express themselves more candidly. It's just more natural.

Justine, you were born in South Africa. Did you grow up there?

Shapiro: We left when I was very young.

Many people compare the historical situation in South Africa, during the apartheid era, with what's happening in the Middle East. Do you feel that, coming from that background, you had a particular sensitivity to these issues?

Shapiro: You know, although I didn't really grow up there, my family is South African and we went back several times. I remember once we had relatives visiting us, and my mom, sister and I were in their hotel room. And my uncle was saying to my mom, "Ach, man, those bloody gorillas, what do they want, eh? They want more, those monkeys, all they do is take, take, take." I was 10 and I remember thinking, which gorillas and monkeys? I couldn't get it, but I knew there was something odd going on, and my mom said, "Girls, I think we're going to go now." She explained it to me later. We were living in Berkeley at the time, so there was a lot of consciousness about race relations. On the other hand, the first time I met Palestinians was in Hebron, prior to making the film. And I remember thinking: Gosh, I've always thought they were terrorists. I don't think so anymore, having met them and got to know them. I realized that we're all so brainwashed, especially prior to Oslo, when the Palestinian Authority and the flag wasn't even relevant. I was thinking the other day about what happened to Vanessa Redgrave. She was practically blacklisted in Hollywood for supporting the PLO.

Goldberg: In some ways she's still blacklisted, even though everyone is talking to the PLO now.

Shapiro: She basically sabotaged her career. And I remember at the time my relatives, and even my 15-year-old self, were like, gosh, how dare she do such a thing?

B.Z., you grew up in Israel. Was this your first time venturing into the Palestinian territories?

Goldberg: No, I had been in a lot of these areas during the intifada with news crews. But it was the first time I stayed for any length of time, talking to people and trying to understand what their lives were like.

Did you have any concerns, as a Jew, before you went or while you were there?

Goldberg: No, I didn't. I was probably stupid. I also tried to be very honest with people about how I felt, and about my own biases.

Did you worry that, with two Jewish filmmakers trying to represent both sides, you might overcompensate for the Palestinian view, so you wouldn't appear biased?

Shapiro: Well, three of us really made this film, and so I think when any one of us had a strong opinion or agenda, we kept each other in check. Every word of the narration was very carefully considered. And the response has actually been amazing from both the right-wing and left-wing press in Israel. It's received nothing but favorable reviews. I mean, if you ask the [Jewish] settlers [living in the West Bank], some of them thought the film was wonderful, but many of them probably don't like the fact that Palestinians are humanized.

Goldberg: They don't like the fact that Palestinians are in it, period. They say the Palestinians have too much airtime.

Shapiro: But the vast majority of Israelis have responded really well. And Arab-Americans have responded well to the film as well.

When the kids speak, you hear how the conflict really comes down to these simple core beliefs that are hard to shake. Has anyone accused you of using children to oversimplify the situation?

Goldberg: We worried people would say that. In fact, I think we have escaped criticism. There have been times, especially in Israel, when people have said, oh, you did this or that wrong. And I say look, we made this film. We hung out in these areas, we met these kids and this is what we saw. And now you're angry that we didn't make it the way you wanted us to make it.

Shapiro: You work for five years unpaid, if you want to!

Goldberg: If you want to make your own film, great. But this is just our story. People take it so seriously because of the power of film to reach mass audiences.

Shapiro: And the importance of the subject.

Goldberg: Some people are just not going to like the film. I've watched, and they sit there looking for something to dislike. And when they find it, the film's over. The criticism I've received in Israel has mostly been about a word here or there. You can see that the person watched the film for 20 minutes, heard a word they didn't like and for the rest of the movie they were formulating their attack plan on me. And I feel bad, because you could have formulated your attack plan after the film. I'm really happy to sit here and be attacked, but it's too bad you missed all these kids. Because they have, I think, a lot to teach us. So the people who criticize the film ...

Shapiro: Fuck 'em!

Goldberg: They weren't going to like it to begin with. And there were other people, Palestinians, who tell me they came looking for a fight.

Shapiro: No wait, they say, I saw the film made by Shapiro, Goldberg -- what are two Jews doing making this film?

Goldberg: This Palestinian woman who saw the film last year told me, "I came ready to tear your film apart, and I'm embarrassed that I have nothing to say. It was so moving."

You were talking after the screening the other day about trying to stay positive, in spite of all the violence on both sides that's going on right now.

Goldberg: I got dressed down at the first screening by a friend, who basically said, "We cannot afford to be realistic. We have to be optimistic." Because I said, "I'm being realistic, what do you want? I'm not optimistic right now, I'm scared, I'm in pain about it." But she sort of reminded me that I do feel, despite it all, that somehow, someway. Maybe only because it makes it easier to get up in the morning. Also, I guess I was trained to pray for peace, and to believe that peace is possible. Maybe it was an abstract idea as a kid. When I was growing up [in Israel], there was no question of what you would wish for if you saw a shooting star, or blew out your birthday candles. You wished for peace. You had no idea what it meant, but it was kind of ingrained in you. And I've grown to see that it's not all that simple. It's going to take a lot of concession, and a lot of pain, and an enormous amount of moral and spiritual courage, from both Israelis and Palestinians, in order to get to any kind of agreement that's going to be vaguely workable for both sides.

Shapiro [to Goldberg]: So, let me ask you a question. In the film, Yarko writes at the Western Wall that his wish is to win the volleyball game. Do you think that now, considering all that's going on, if Yarko was taken to the Wall, he'd write for volleyball, or for peace?

Goldberg: I think he'd write for volleyball.

Shapiro: Still?

Goldberg: His life is so enmeshed in volleyball. I also grew up in a really different time than Yarko. Now the violence is small-scale, one person, 20 people, five people, very targeted, it happens at certain flash points. I grew up in a period where 5,000 Israelis or 20,000 Egyptians would be killed. We were wishing for peace to end the wars. And in a way those wars have already ended. It's bizarre, but there's a certain kind of peace that's come to the land already, in that there is no all-out war going on in the Middle East. And it doesn't look like there's going to be one in the near future. Maybe that's a silly thing to say, because you never know what's going to happen in Iraq, what's going to happen with Iran, who the United States is going to bomb next, who's going to retaliate, if Israel's going to get involved. So I don't know. But I also didn't play volleyball.

What's next for you?

Goldberg: Sleep?

Would you like to collaborate on another project?

Shapiro: You know, in a way this job has just begun because we're learning that you have to work really hard to get people to see a documentary film. It's expensive going to the movies, a babysitter is $10 an hour. To go to a movie for two, it's like a $60 evening. So to convince people to see a documentary about the Middle East? That's kind of our job right now, to encourage people to make that choice.

A good way would be to tell people about how funny this film is.

Shapiro: You see? I agree with you, because this is what I've heard over and over again. People say, I didn't expect to find myself laughing in a film that's about the Middle East conflict. And that's just the best feeling, to hear the audience laughing. It opens them up to the crying part.

Did you expect it to be that funny?

Shapiro: B.Z. and I had a great time when we went out in 1995. It was just the two of us, doing everything on a shoestring. We had no idea of what we were getting into, and it was just such an incredibly innocent time. Every day we learned so much. And it was so complicated, and often so disheartening, that you had to deal with it with humor sometimes. The funniest people I know are people who came from really abusive families. Then when we started working with Carlos, the three of us would have to diffuse the tension with humor. And kids are funny, despite themselves. That age group, they're just weird! We were really enjoying these kids, and we wanted the audience to enjoy them as well.

That burping contest!

Shapiro: That was amazing, you know, that was one of those things where you just know there's a God. It's like, there's tape in the camera, the cameraman's not taking a cigarette break, the battery's charged, it was one of those incredible magic moments. But then, when you're shooting that much footage you sort of deserve a few magic moments.

Shares