The decision to make a sequel is almost always a business decision. Though spinoffs may be good for the bank account, they're usually bad for art. The general rule is that with each new installment the overall quality drops (think "Meatballs III," "Lethal Weapon 4," "Rocky V"). Serious artists don't work on the installment plan.

But don't tell this to Philip Roth.

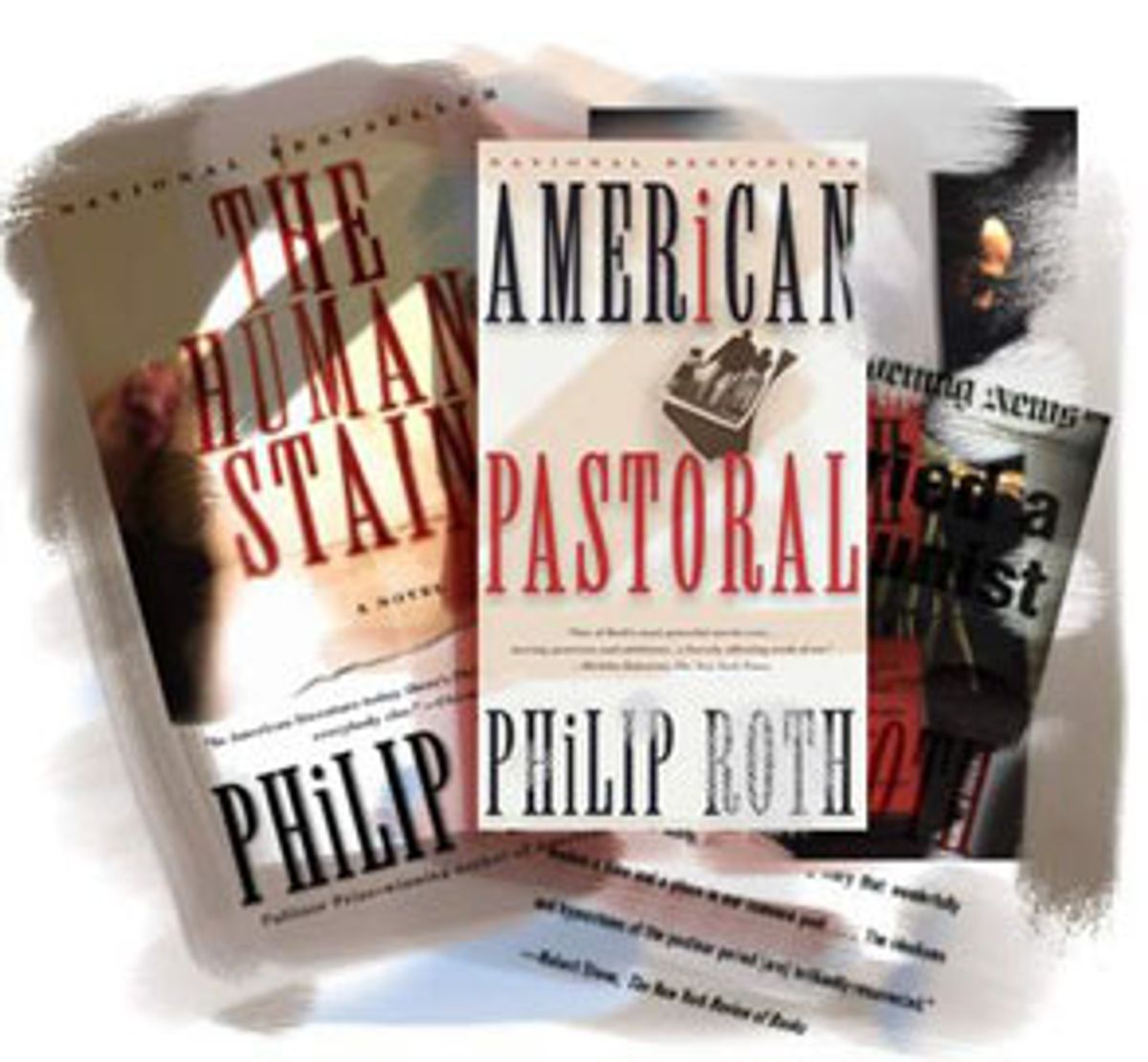

Over the past 21 years the 68-year-old novelist has published the most ambitious literary series of our time: the Nathan Zuckerman books. Taken together, these eight interlocking volumes -- a trilogy and epilogue ("Zuckerman Bound"), a stand-alone novel ("The Counterlife") and a second trilogy ("American Pastoral," "I Married a Communist" and "The Human Stain") -- form an awe- if not envy-inspiring masterpiece. Who knew that authors could still write on such a Proustian scale? The Zuckerman oeuvre weighs in at 2,215 clothbound pages, not counting Nathan's letter to Roth in the author's autobiography ("The Facts").

The hubris! The chutzpah! The word count! Who but Roth would dare pen eight books featuring a single embattled novelist -- "a being," as he writes in "The Facts," "whose existence was comparable to my own and yet registered a more powerful valence, a life more highly charged and entertaining than my own"?

Of course, neither Roth nor Zuckerman is a universally beloved character. Many readers have criticized them both for being narrow, misogynistic, self-involved and self-loathing. And while Roth's fictional Song of Self was too much for some people, he seemed, for a long time, incapable of writing any other way. "One's song isn't a skin to be shed -- it's inescapable, one's body and blood," he once wrote. "You go on pumping it out till you die, the story veined with the themes of your life, the ever-recurring story that's at once your invention and the invention of you."

The Zuckermania begins with the brick-thick "Zuckerman Bound." This book, which combines the early Zuckerman novels ("The Ghost Writer," "Zuckerman Unbound," "The Anatomy Lesson") and a novella ("The Prague Orgy"), covers events from 1956 to 1976, with the odd flashback to Nathan's Newark childhood. It engages us not just because of Roth's formidable intelligence and humor but because Zuckerman's themes -- the familial ambivalence, Nathan's women problems, the difficulties caused by autobiographical fiction -- intensify as we page through the stout volume.

The genius of the first four Zuckerman books is their recursive nature; they illustrate in vivid detail that the child is the father of the novelist, and that analysis is always interminable. We're shown the origin of every twitch of Zuckerman's psyche. For instance, when the 30ish Nathan explains to his mother about his third divorce -- "I just don't have the aptitude for a binding, sentimental attachment to one woman for life" -- we remember how the unmarried Nathan cheated on his girlfriend Betsy when he was 23. (He recalls struggling to undress this second lover, while she, "not resisting all that strenuously ... told me what a bastard I was to be doing this to Betsy.") We also recall what Nathan's mentor, the short-story writer E.I. Lonoff, told him in "The Ghost Writer": "You don't chuck a woman out after thirty-five years because you'd prefer to see a new face over your fruit juice."

Father figures like Lonoff abound in "Zuckerman Unbound." Usually Nathan is out to win their approval, but sometimes he squares off with them in Oedipal battle. Consider Milton Appel, a literary critic who tears into Nathan's work in print and then asks him to write an Op-Ed piece in support of Israel for the New York Times. This prompts Zuckerman, who worshipped Appel when he was young -- and who, in "The Anatomy Lesson," suffers from an undiagnosable pain -- to pick up the phone and shout (at the top of his doped-up voice):

"Milton Appel, the Charles Atlas of Goodness! Oh, the comforts of that difficult role! And how you play it! Even a mask of modesty to throw us dodos off the track! I'm 'fashionable,' you're for the ages. I fuck around, you think. My shitty books are cast in concrete, you make judicious reappraisals. Oh, I'll tell you your calling -- President of the Rabbinical Society for the Suppression of Literature in the Interest of Loftier Values. Minister of the Official Style for Jewish Books Other than the Manual of Circumcision. Regulation number one: Do not mention your cock. You dumb prick!"

Even when he's not drugged to the gills, Nathan's indecorous honesty and novelistic ruthlessness cause him to alienate just about everyone. Things get so bad that his podiatrist father calls him a "bastard" on his deathbed (instead of offering Dr. Zuckerman a loving goodbye, Nathan lectures him on the Big Bang). This leads his brother Henry to accuse him of murdering the old man by publishing his "Portnoy"-esque novel, "Carnovsky":

"Do you really think you can just go have a good time with the rest of the swingers without troubling yourself about your conscience? Without troubling about anything but seeing how funny you can be about the people who loved you most in the world? The origin of the universe! Oh, you miserable bastard, don't you tell me about fathers and sons! I have a son! I know what it is to love a son, and you don't, you selfish bastard, and you never will!"

But the bastard and Henry aren't through. They meet again in "The Counterlife," perhaps the most experimental of all the Zuckerman books. Here Roth imagines some life-and-death scenarios for both Zuckerman and his brother Henry (both of whom "die" in the course of the book). Yet even "The Counterlife" looks back at "Zuckerman Bound." When Henry flees his life as a New Jersey dentist to become a gun-toting Zionist in Israel, we think of the scene in which Dr. Zuckerman squashed Henry's college dream of becoming an actor ("not even Paul Muni as wily Clarence Darrow, not even Paul Muni live in their living room as patient Louis Pasteur could have persuaded Dr. Zuckerman that a Jew in pancake makeup on the stage was probably no more or less ridiculous in the eyes of God than a Jew in a dental smock"). In "The Counterlife," in Israel, Henry is still fighting to act:

"Henry, to make himself more comfortable, draped his field jacket over the back of his chair, the pistol still in one pocket. That's where he'd been carrying it during our tour of Hebron. Shepherding me through the crowded market, he pointed out the abundance of fruits, vegetables, chickens, sweets, even while my mind remained on that pistol, and on Chekhov's famous dictum that a pistol hanging on the wall in Act One must eventually go off in Act Three. I wondered what act we were in, not to mention which play -- domestic tragedy, historical epic, or straight farce?"

Had Roth dropped the curtain on Zuckerman after "The Counterlife," many people would have been satisfied. But that's not what happened. Instead, between 1997 and 2000, he published the new Zuckerman books. Three very different Zuckerman books: "American Pastoral," "I Married a Communist" and "The Human Stain." We were unprepared.

These three works, which ushered the era of what we might call the Historical Zuckerman, finally allow Roth's hero to move outside himself. Which, until the late '90s, was a dangerous thing ("If you get out of yourself you can't be a writer because the personal ingredient is what gets you going, and if you hang on to the personal ingredient any longer you'll disappear right up your asshole," he writes in "The Anatomy Lesson"). The new books minimize the personal ingredient in an unprecedented way. Roth keeps Zuckerman at the helm -- he remains the narrator -- but he's no longer the main subject. Instead he puts three new characters (Zuckerman's high school acquaintance, Swede Levov; his boyhood mentor, the radio actor Ira Ringold; and his neighbor, Coleman Silk) in three historical situations ('60s radicalism, '50 Communist witch hunts, '90s political correctness) where Zuckerman used to be.

The new selflessness is shocking. In "American Pastoral," for instance, Zuckerman reveals that prostate surgery left him impotent and incontinent, a fact he mentions briefly on Page 28 and then again -- less briefly -- on Page 51. The old Nathan would not have been so circumspect.

What happened? The new books seem to recognize the existence of other people. Or, rather, the fact that other people can be as endlessly fascinating and unknowable as Nathan Zuckerman. This new approach might well be summed up by a passage in "American Pastoral":

"You fight your superficiality, your shallowness, so as to try to come at people without unreal expectations, without an overload of bias or hope or arrogance, as untanklike as you can be, sans cannon and machine guns and steel plating half a foot thick; you come at them unmenacingly on your own ten toes instead of tearing up the turf with your caterpillar treads, take them on with an open mind, as equals, man to man, as we used to say, and yet you never fail to get them wrong. You might as well have the brain of a tank. You get them wrong before you meet them, while you're anticipating meeting them; you get them wrong while you're with them; and then you go home to tell somebody else about the meeting and you get them all wrong again."

But things haven't changed that much. Family conflicts still drive these late-model Zuckerman books, but now they're found outside the Zuckerman clan. Coleman Silk, for example, the light-skinned black man who decides to pass himself off as white in "The Human Stain," faces a whole different family struggle. Listen as Roth describes Coleman telling his mother that she'll never see his white wife or his children:

"He was murdering her. You don't have to murder your father. The world will do that for you. There are plenty of forces out to get your father. The world will take care of him, as it had indeed taken care of Mr. Silk. Who there is to murder is the mother, and that's what he saw he was doing to her, the boy who'd been loved as he'd been loved by this woman. Murdering her on behalf of his exhilarating notion of freedom! It would have been much easier without her. But only through this test can he be the man he has chosen to be, unalterably separated from what he was handed at birth, free to struggle at being free like any human being would wish to be free. To get that from life, the alternate destiny, on one's own terms, he must do what must be done."

Roth's brilliance here -- and we cannot overpraise this -- is that he found an entirely new way to tell Zuckerman stories. Judging from the energy and expanded vision in the latest trilogy, you have to conclude that Roth's not done yet. It's hard to imagine what the next Zuckerman book will look like, though it wouldn't be if we possessed Philip Roth's ridiculously vigorous imagination.

Shares