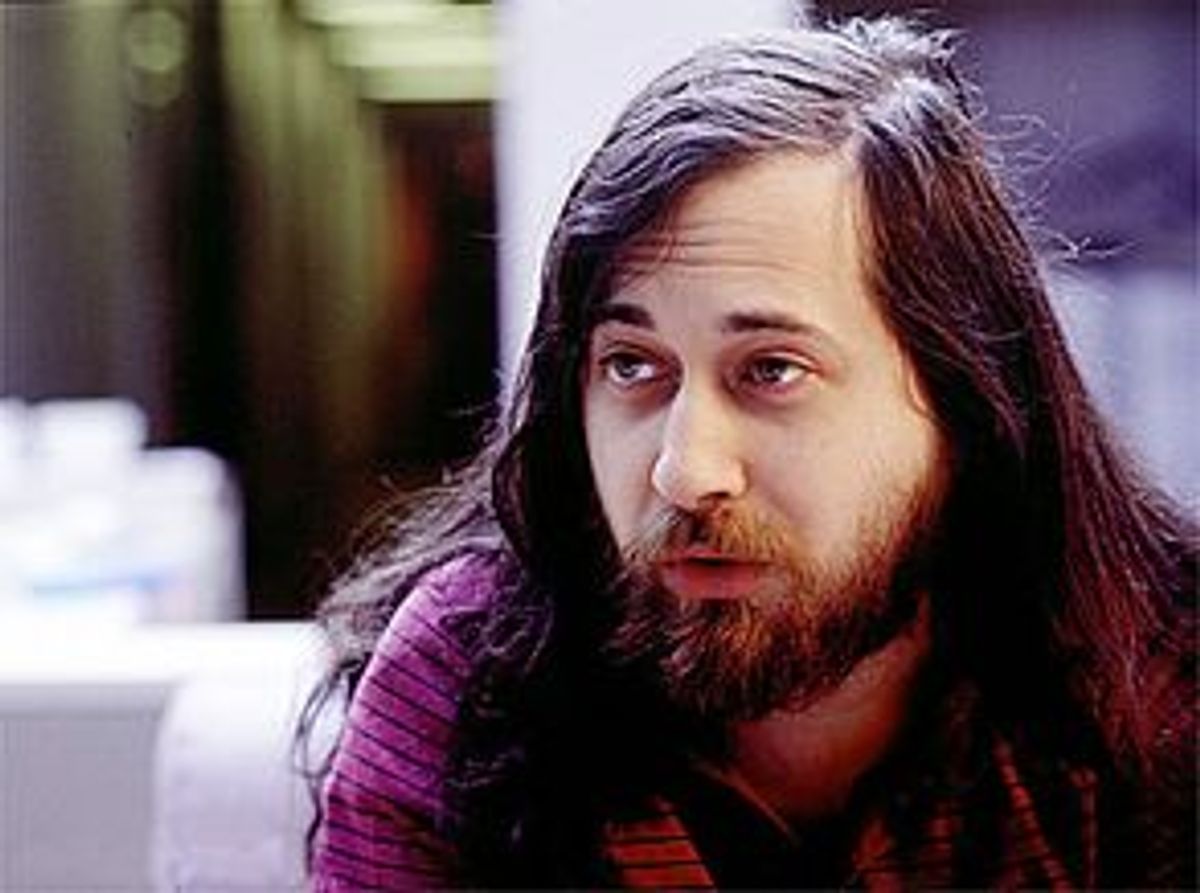

In the fall of 2000, Sam Williams, author of "Free as in Freedom," sent me an e-mail asking me if he could discuss an ethical question about Richard Stallman. I had to smile. I didn't know Williams personally, other than as a journalistic colleague who covered the free-software/open-source software beat, but I could easily imagine what the trouble was. Stallman was being prickly, and a prickly Stallman is no fun.

Williams was in a jam. He had completed some preliminary work on a book about Stallman, including two lengthy in-person interviews. But the publisher of the book was balking at some of Stallman's requirements. Stallman wanted the book to be freely reproducible, just like the software that Stallman fights for with every breath. Stallman was threatening to withdraw his cooperation, and Williams was unsure whether he could morally use the material he had already gathered.

I couldn't give Williams any useful advice, other than to confirm what he already knew, which is that in the world of top-notch computer programmers, where stubborness is almost an entrance requirement, Stallman reigns supreme. He will not bend and he will not break, and if you want to dash your head against his rock, you must be willing to accept the brain damage that will undoubtedly result.

In the end, "Free as in Freedom" was published by a different publisher, and under a license that Stallman could live with. All's well that ends well -- particularly for readers, who get to benefit from a nuanced, detailed picture of Stallman that includes much that will be new even to close followers of the free-software movement.

That in itself is an achievement. Stallman is not publicity shy. He has been the subject of numerous profiles, including an elegiac chapter in Steven Levy's "Hackers," and he has a prominent role in the cluster of recent books chronicling the rise of free and open-source software (that branch of the software industry in which code is made publicly available, rather than kept proprietary, as is the case with software produced by corporations such as Microsoft). Stallman's own prodigious output of words -- transcripts of speeches, essays, Usenet News postings -- is available online in intimidating quantities.

But Williams uncovers details of Stallman's upbringing -- his family life, his adolescence, his Harvard years -- that bring fresh insights into the evolving mind-set of one of the most influential programmers in the history of computer software. Covering ground that many have covered before, he still manages to bring out details of Stallman's psychology that are fresh and compelling.

In high school, Stallman got A's in math and physics, but he failed English because he adamantly refused to write essays of any kind. Williams speculates that Stallman may be mildly autistic, or even suffer from Asperger's syndrome, and he supports the theory with numerous observations from family and friends. Even in high school, other gifted math and science geeks were alienated by Stallman's out-of-kilter inability to socialize.

The product of a broken home, Stallman had unhappy relationships with both his parents. At the same time, his father fought in WWII and then protested the Vietnam War, and his mother worked to reform the Democratic Party; those influences helped shape an uncompromising activist unafraid to challenge the powers that be.

As an undergraduate at Harvard, where he discovered a passion and a talent for folk dancing, Stallman displayed an aptitude for math that dazzled his fellow students. He is often called a genius by his admirers, but Williams digs deeper into the details, and shows us some of the truly amazing feats he was capable of, whether they were programming stunts or displays of pure math brilliance.

And yet, possibly the most interesting question in the book is left unanswered, although not for lack of trying. What will Stallman's legacy be? Visionary hero who changed the world, or Don Quixote tilting at windmills? Pioneer, or flash in the pan? The answer changes according to the rising and falling fortunes of free software itself -- which makes it all the more interesting to ask the question now, in 2002, when software hackers are no longer countercultural heroes able to command huge salaries on a whim.

In "Hackers" both Levy and Stallman refer to Stallman as the last hacker on earth -- the lone remaining survivor of a nearly extinct tribe. And even in 1998, when I spent a day following Stallman around Palo Alto, he exuded a vaguely tragic aura. He was anxious that his role in the free-software movement was being written out of history, that usurpers like Linux creator Linus Torvalds were getting credit for achievements that rightfully belonged to him. The rise of use of the term "open-source" software, a business-friendly label explicitly meant to be distinct from the more moralistic "free software," was particularly grating.

But as Williams points out, no matter what you call it, the cultural and economic phenomenon of free software at the turn of the century was one of the best things that ever happened to Stallman. In 1999 he was suddenly speaking to crowds in the tens of thousands at LinuxWorld conventions. If he'd had his way, they would have been called GNU/LinuxWorld conventions, thus giving proper respect to the GNU software project that Stallman spearheaded -- but in any case, the rise of Linux meant that Stallman was suddenly delivering his personal peroration on the moral imperative of free software to a greater audience than ever before.

And even as the dot-com boom imploded, and the economic model underlying attempts to cash in on open-source software collapsed, Stallman's star continued to rise. Today he is in huge demand for speaking engagements across the globe. He is the co-recipient, along with Linus Torvalds, of Japan's Takeda Award in 2001 (worth approximately $268,000). Stallman continues marching along, even as many of the magazines that profiled or otherwise covered him are gone.

Today, when it already seems almost anachronistic to talk about the free-software "movement," Stallman's concerns about the corporate mandate to make information proprietary put him squarely in the middle of the digital era's most simmering hot spots. The extension of copyright at the behest of corporate mega-conglomerates like Disney, the battle over whether copy protection should be mandated by federal law, the questions of what kinds of information individual users have a right to redistribute and what they don't -- all of these issues connect directly to Stallman's heartfelt beliefs.

Looking ahead, one can imagine at least three possibilities: In one scenario, profit-seeking corporations intent on carving out proprietary domains win the day. Microsoft's .Net usurps control of the Internet from the world of open standards. Hollywood ensures that every single time you listen to a snatch of music or watch some video, you pay a toll. Patent and copyright law squelch any attempt by independent hackers to create nonproprietary software solutions. In that world, Richard Stallman's legacy might be the same as Ned Ludd's -- doomed to be remembered as just another foolish mortal who tried to turn back the tide.

Or the opposite: Free software proves to be everything its proponents say it is -- a low-cost, highly efficient, morally persuasive strategy for software development that is as unstoppable as the Internet itself. The power of corporations to dictate the to's and fro's of the software marketplace is broken, with incalculable public benefit as billions of world citizens are empowered by their access to cheap productivity tools. Neither Hollywood nor Congress is able to stop the redistribution of digital information, with the result that new business models for rewarding creative brilliance are formed, to the benefit of artist and entertainment consumer alike, if not Sony or AOL Time Warner or Disney. In this future, Stallman would be more like Gutenberg or Edison, a visonary innovator whose contributions form the bedrock of the modern world.

Or, as is most likely, the future plays itself out as a mix of contradictory forces: Free software spreads at the same time as do corporate assaults on consumer liberty. Microsoft continues to mint money and the Net continues to stay out of any single entity's control. Patents continue to get filed and hackers continue to find workarounds.

Where does Richard Stallman fit into that future? Footnote or founding father? The real answer may be that it doesn't matter. As Stallman says to Williams, "I've never been able to work out detailed plans of what the future was going to be like ... I just said 'I'm going to fight.' Who knows where I'll get?"

There's something comforting about Stallman's intransigence. Win or lose, Stallman will never give up. He'll be the stubbornest mule on the farm until the day he dies. Call it fixity of purpose, or just plain cussedness, his single-minded commitment and brutal honesty are refreshing in a world of spin-meisters and multimillion-dollar marketing campaigns.

One could easily imagine the author of a biography of Stallman coming out of the project hating his subject, or at least completely sick of him. But despite the torment that Williams acknowledges feeling at several stages, at the end, his feeling is one of compassion and respect for the force of nature that is Richard Stallman. Stallman is no fool striving to roll back the tide -- he is the tide.

Shares