It's cold and muddy. Israeli soldiers have just fired tear gas and percussion grenades at a large crowd of peace activists gathered at the entrance of Ramallah to protest Israel's military operations in the West Bank. Aviva Weisgal, an Israeli mother of two, is doubled over, crouching between parked cars and trees, trying to escape the noxious cloud without giving in to panic.

"Now that's real bravery," she says between coughs, referring sarcastically to the soldiers' show of force against unarmed demonstrators. Nearby, an old Palestinian woman, overcome with stinging fumes, falls hard to the ground. People scream for a doctor, men and women share water and onions to recover their breath. A little boy watches and visibly shakes with fear.

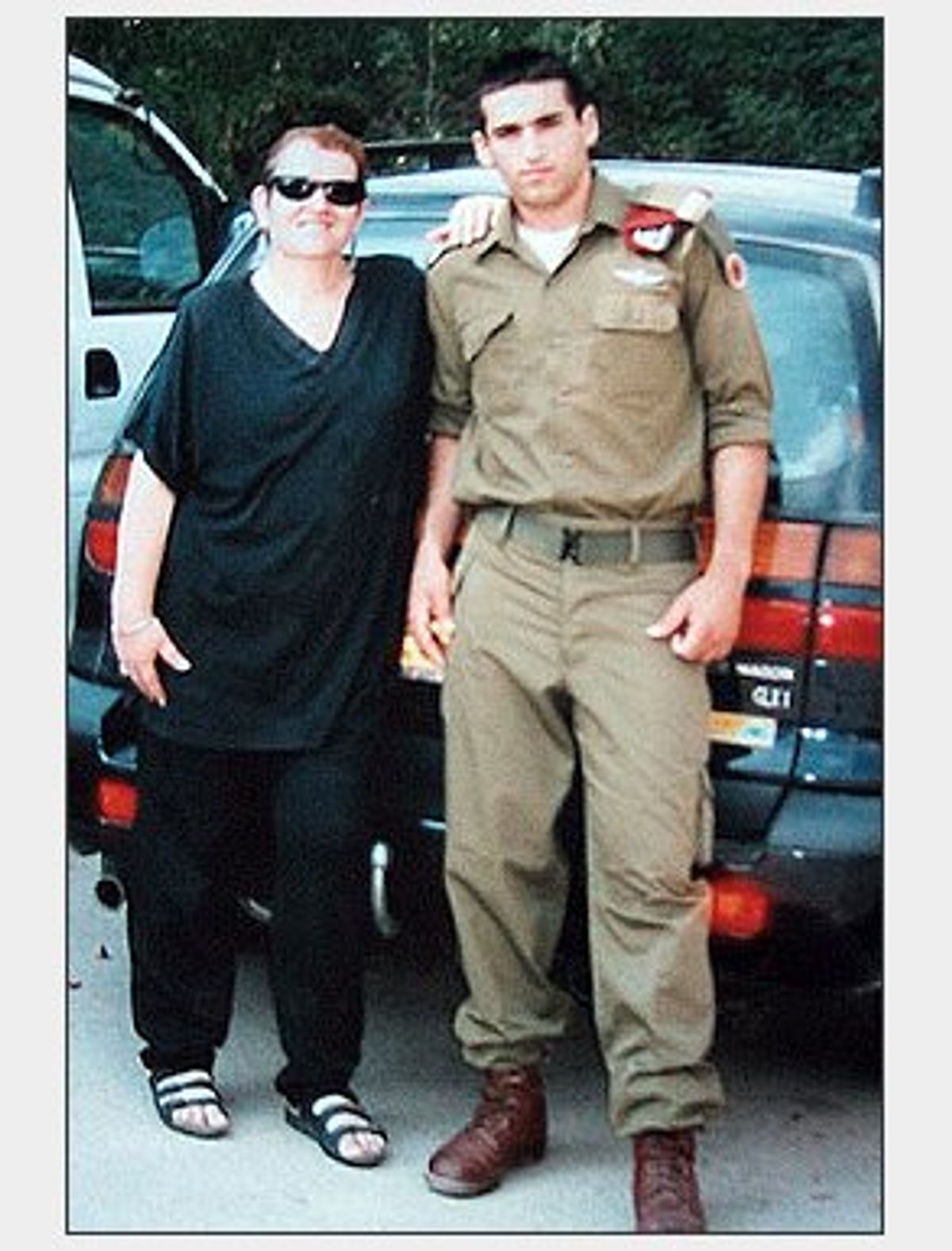

Days earlier, in her home on a kibbutz just west of the city, pacifist Malka Tezmach takes a quiet, but equally provocative stand against the violence. Her son, Tal, was killed in his sleep by a Palestinian commando on March 19 while serving in the Israeli-occupied Jordan Valley. Malka, her voice infused with terrible grief, refuses to call for revenge. Instead, she makes statements that infuriate those who demand retaliation.

"We saw pictures on television of the terrorists who came [to the Israeli training camp where Tal was serving]," says Tzemach, a 49-year-old nurse with short red hair and a weary expression that reflects strength and exhaustion. "I know people who saw them. Many curse them. But I was so angry and I'm so angry still that I can't direct my anger at them specifically. I'm angry at the bad people on both sides. I'm angry at the situation.

"I don't understand how for so many years we've allowed people to be killed without doing anything to stop it," she goes on. "My fear now is that a friend of Tal's will be killed. I can't tolerate that even a friend of his friends will get killed. How will we keep on living through all the loss?"

Weisgal and Tzemach are members of Women in Black, a group of women who have held silent vigils for peace at major intersections around the country at the same hour every week for almost 15 years. In the past, the demonstrations have been uneventful, rarely marred by conflict more serious than name-calling. But in these chaotic times, marked by seemingly endless bloodshed on Israeli and Palestinian sides, women like Weisgal and Tzemach are coming out in greater -- and louder -- numbers, risking more than ever to voice opposition to what they see as a senseless war.

On Wednesday, Jewish and Israeli Arab women were supposed to march from Jerusalem to Kalandia, a checkpoint at the entrance of the West Bank city of Ramallah, to show solidarity with a Palestinian women's group stuck on the other side. But a special army roadblock kept the women away from the Kalandia checkpoint, and the peace rally became confrontational when it was hijacked by more aggressive male demonstrators and politicians.

Despite the setbacks, turnout for the march was impressive (more than 2,000 people showed up), and it emboldened women trying to throw a wrench into the Israeli-Palestinian war machine. "There's a growing number of women who are saying: 'Enough, I don't want to take part in this,'" says rally participant Magdalena Hefetz, a member of Women for Human Rights, an Israeli group founded last year that monitors the behavior of Israeli soldiers at checkpoints.

A growing number of Israeli pacifist women, many of them anxious mothers with draft-age children, are bringing their nonviolent message to bear on a bloody, testosterone-charged conflict. They are challenged by others, including Women in Green, a group based in a West Bank settlement that favors continued military response and retaliation. But as Israeli military and political figures have raised the volume on calls for more punitive strikes and wide-scale military actions, women against the war have responded with new vigor, publicly questioning the rationale of aggressive policies that carry a high cost in human lives.

It is difficult, at this point, to say exactly how many Israeli women are currently engaged in the fight for peace. Women in Black is not an organization of card-carrying members but rather a peace network that provides a framework for women wanting to express opposition to war and the occupation of the West Bank and Gaza. The group was inspired by Argentinian "mothers of the disappeared" who have gathered every Thursday in the Plaza de Mayo in Buenos Aires for more than two decades to demand news of their missing children. Women in Black now has chapters around the world -- in the U.S., England, Italy and also in Serbia, where women bravely protested against Belgrade's violent tactics.

Weisgal says she doesn't know how many women participate in vigils in Israel these days. At her particular intersection, on a secondary road south of Jerusalem, about nine women show up every Friday. But Weisgal believes the movement is gaining momentum.

"After a gap of several years when we thought peace was on track, women are returning to the vigil [organized by Women in Black]," she says, in the minutes before tear gas breaks up the rally. "It's hard because every five minutes you hear about a new suicide attack, and people who used to drive by our signs saying 'Stupid women' are now much more aggressive towards us.

"But every voice counts," insists Weisgal. "I'm worried for my children. I have a 15-year-old boy and a 16-year-old girl, and I don't want them to serve in the army."

Weisgal says her son would rather do some sort of civilian social work than raid Palestinian houses or shoot tear gas at unarmed demonstrators. "He says it would be more brave to work with old people or disabled children than to be a soldier," says Weisgal, a 47-year-old schoolteacher. "But I'm afraid that by draft age, peer pressure will take its toll."

Many of the women's organizations agitating for peace also lobby for alternatives to compulsory military service. They want a legal alternative to service for conscientious objectors, who now face three months in prison for refusal to join the army. The women's proposal got a big boost recently, when hundreds of Israeli reservists announced publicly that they would no longer serve in the territories occupied by Israel since 1967.

"Sisters and mothers of the refuseniks [as the reservists are called] are becoming active, getting involved in various organizations. It's great," says Hefetz. "It's just a little bit too late -- 35 years too late."

Too late, certainly, for Tal Tzemach.

"My son was killed because of the occupation," says Malka Tzemach. Some Israelis would vow revenge and cultivate hatred for Tal's assailants. Some would take pride in the fact that Tal, a second lieutenant promoted in his death to first lieutenant, was defending his country. But Malka says she will not let grief interfere with her beliefs -- if anything, it strengthens them.

"For a long time I've believed that we treat Palestinians unfairly," she says. "When my son was killed I couldn't switch off those feelings and think suddenly about how terrible the Palestinians are and how virtuous we Israelis are. My impression is that life isn't really important to us. I see it in our treatment of our enemies -- if we can call them enemies. We're contemptuous of them, and in the end we cheapen our own lives."

It would be easier for Tzemach to believe her son did not die in vain. But Tzemach dismisses the argument that Israel must fight and maintain troops in the occupied territories in order to protect the Jewish heartland from terrorist attacks. "We believe our own propaganda," she says. "Since the Gulf War [when Iraqi Scud missiles reached Tel Aviv], we know the Golan Heights and the Jordan Valley don't really matter. Security is just an argument we cling to in order to justify ourselves. You can say the land is ours, we don't want to give it back -- that's a different story. But it has nothing to do with security."

Tzemach sees the occupation of the territories seized by Israel in the 1967 Six Day War as the root of all evil. For her, the occupation provides motivation for Palestinian terrorists and corrupts the behavior of Israelis. "Even traffic accidents are related to it," she says. "It has turned us into aggressive macho people who don't care about each other."

Israel's repeated conflicts with Palestinians and Arab neighbors also have created a suffocating narrative in which militaristic values are extolled and war is celebrated as the nation's finest hour, says Tzemach. "Friends come into my house and speak about the army with pride, exulting in what the army did in the past. All the stories and boasting about the army is what keeps the conflict going," she says, expressing a belief over which she and her husband, David, frequently butt heads.

Like other Israelis his age, Tal was deeply moved by the assassination of Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin in 1995, says Malka. In fact, Tal and many of the soldiers fighting today were part of the "candle generation" that mourned Rabin's death, and called for peace, at candle-lit memorials across the country. "We were at the peace demonstration where Rabin was killed," says Tzemach. "After that, I took the kids to all the demonstrations I could. Tal told a pen pal in Canada that he was very happy when the Oslo accords were signed and very happy with the withdrawal from Gaza and Jericho.

"But when he joined the army," says Tzemach, "we stopped talking politics. I would show him interesting articles from time to time, that's it."

Tzemach had mixed feelings about her son serving in the army. "All these years he was told that it's important to serve, that it's important to contribute to the security of your country. At a demonstration recently, I met women who taught their sons from age zero not to go in the army. It wasn't our way."

."Now that [Tal] is dead I understand we really put these youths in a terrible situation," continues Tzemach. "They're bombarded with messages about protecting the homeland, messages sometimes of indifference and hatred. Without this mental preparation, soldiers couldn't do what they're doing. They stop asking questions and adopt a defensive position."

"There are soldiers in my living room right now," she says. "Friends of Tal's come to pay their condolences. I keep quiet because I don't want to create friction. But I believe Sharon hasn't reached the point of orgasm yet, that's why he's continuing this war."

One of Tzemach's close friends, a woman who, like Tzemach, joined Women in Black during the Jerusalem riots of 1996, pipes in with the kind of feminist and pacifist opinion that is the group's trademark.

"We're holding Arafat. What's next?" says Laurie Handel. "I think women would worry about the consequences. But here it's like the Wild West, you draw guns first and think later. As a mother, we can say 'OK, you win the fight, and then what?'" By ending the occupation and giving in to Palestinian demands, says Handel, "I get my son back, he'll be safe at home. It's not that we love Palestinians. But I'm not afraid of losing face. As women we know very well how to lose face -- we do it several times a week."

Weisgal believes that instant Israeli retaliations to Palestinian attacks come from a deep-rooted dread of being perceived as passive. "[Israeli men] are gung-ho for the war," she says. "It's how they demonstrate their bravery. Other ways are considered passive, and there's the feeling that if we don't answer with violence, Palestinians will think we're willing to go to our deaths like sheep."

The shadow of the Holocaust is difficult to shake, she says. So, too, is the feeling of revulsion caused by suicide attacks -- whether carried out by men or, recently, by young women. "It's horrific no matter who does it," says Weisgal. "But it certainly doesn't push women forward in Palestinian society. All it does is make Israel a little less confident in its ability to defend itself."

Although Israel's women's groups rarely have an effect on government policy, there is a precedent that gives today's pacifists some hope for success. When Israel pulled out of Southern Lebanon in May 2000, after nearly two decades of war, a women's organization called Four Mothers was credited with helping rally Israeli public opinion behind the move.

Right-wing politicians like Prime Minister Ariel Sharon, then the leader of the opposition Likud Party, harshly criticized the army pullout as caving in to the guerrilla tactics of Hezbollah, a fundamentalist organization backed by Iran and Syria, and argued it would hurt Israel's deterrence. But in countless interviews and opinion pieces, the Four Mothers -- women who lost their sons in the Lebanon war -- helped focus the debate not only on security issues but on the young lives that would be saved by putting an end to what was being labeled as Israel's Vietnam -- a war against guerrilla fighters on foreign land with victory nowhere in sight.

The Four Mothers spawned a group called the Fifth Mother, which is now agitating, like Women in Black and a half-dozen similar women's organizations (Daughters of Peace, the Coalition of Women for Peace, and others), for an end to the occupation of the West Bank and Gaza. But the battle is much tougher now, says Hefetz, one of the peace activists braving the rain and tear gas at Wednesday's rally. "Many people feel we're not occupiers and that [the West Bank and Gaza] is our land. In Lebanon, it was much clearer. There was a border and it was a different state."

The lack of national consensus over the facts of occupation and the tension created by repeated terrorist attacks cause many people to have little patience for female pacifists, who are easily dismissed as sissies and dreamers. At the Nahshon junction, the intersection where Tzemach, Handel and Weisgal stand vigil with a handful of other women every Friday afternoon, insults and even physical violence are more and more common.

According to Handel, most of the barbs are laced with sexual innuendo ("Why don't you sleep with Arafat? You probably haven't been properly laid in a long time") or target the families of the demonstrators ("I hope your children all die"). They've been flashed and spat on, and a few months ago, four men came out of a van, pushed a woman to the ground and destroyed their signs. "They attacked us because we're women," says Handel. "They wouldn't have dared if there were men with us."

The trick is not to react, says Hefetz, who's been pestered -- including by right-wing women -- during her work as a peace activist helping Palestinians cross Israeli army checkpoints around Jerusalem. "Soldiers tell us to go back to our kitchen, but it's OK," she says. "Women know how to ignore provocation. It's men who always have to react."

Meanwhile, the mere presence of women at the checkpoints, the scene of tense and often humiliating transactions between Israeli soldiers and Palestinian civilians, is beneficial, she says.

"It's good for the soldiers. They have the feeling that their mothers are watching, so they behave better."

Shares