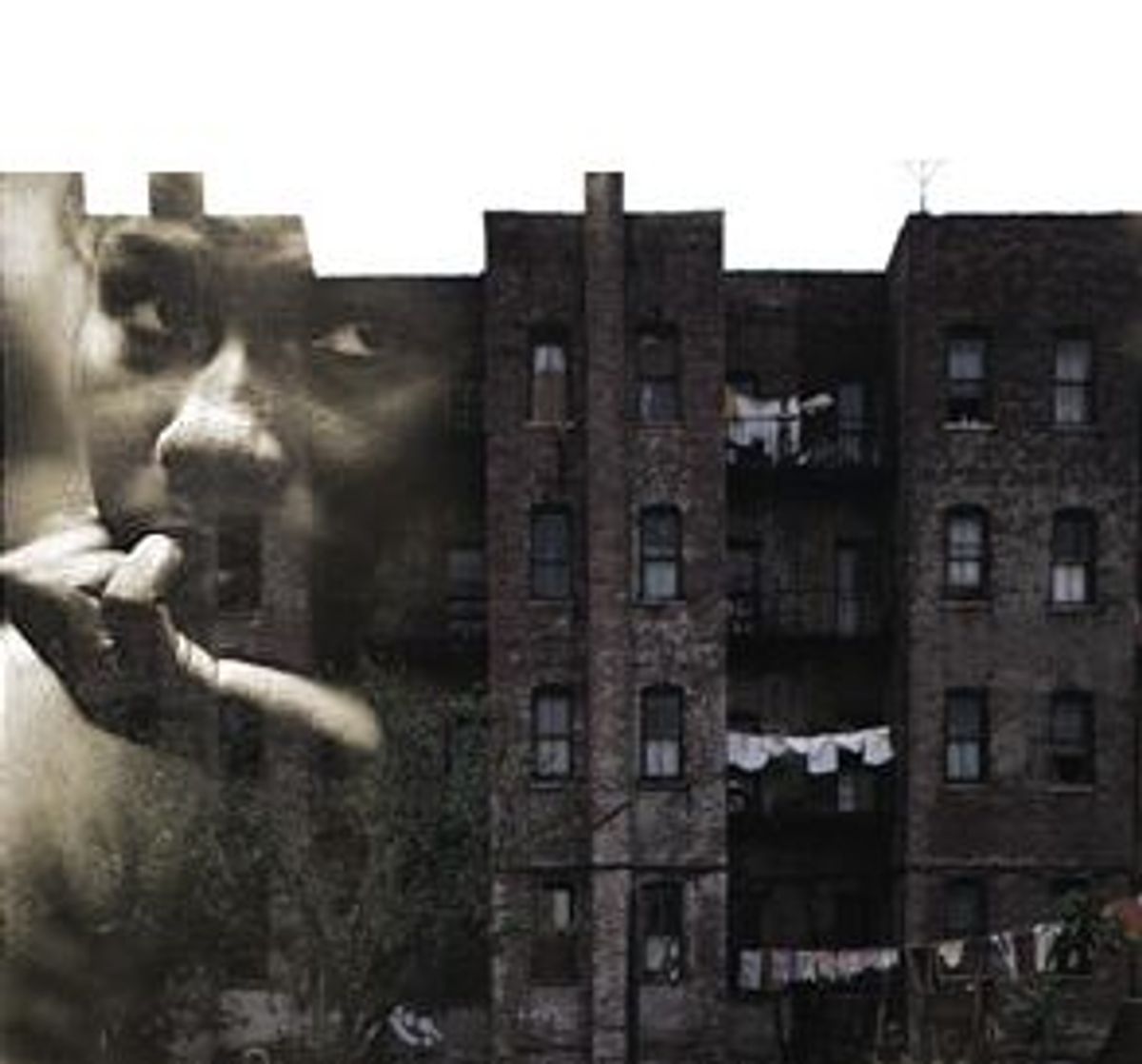

At 10 a.m. on a recent Friday, the housing projects at 531 Bay Street are mostly deserted. The stairs reek of urine, there's a broken shopping cart hanging upside down over the edge of the concrete balcony. Two sullen boys hang around a denuded courtyard.

Alma Lark squints down from the third-floor balcony. Behind her, 8-year-old Nefertiti watches from behind an iron grille on their apartment door. She and her sister came to live with Lark, their grandmother, when their mother, addicted to drugs for almost 20 years, couldn't care for them anymore.

"Are the boys there?" Alma asks nervously. "They here every morning, selling the drugs."

Lark doesn't know the boys. They don't even live in the housing project. But today, in the wake of a Supreme Court ruling earlier this month, Lark's future -- along with the future of her grandchildren -- is tied to the teenage strangers. Their behavior, long an annoyance to Lark, is now a threat to her well-being.

Under the terms of a 1996 law upheld by the court, any public housing resident can be evicted from his or her apartment if anyone living in or visiting their home is discovered using drugs, or participating in other criminal activity. The rule means that Lark, already overwhelmed with the business of mothering, has to take on the role of cop. If she wants to stay in her apartment, she has to make sure that no one in it -- friends, visitors, her addicted daughter -- takes drugs, sells drugs, hangs out with drug dealers or commits any crime. If she fails, she could be evicted.

"When you live in public housing it's a challenge all the time," Lark says. "You have drug activity around the building and young people trying to get other children involved in the activity."

And increasingly, there are few activities to offer as alternatives to drug activity. Even as the Supreme Court upheld the One Strike rule, as the eviction law is called, the Bush administration is eliminating programs that have been successful in reducing drug use and crime in public housing. The Public Housing Drug Elimination Program -- started in 1989 to direct $345 million annually to special police enforcement, youth initiatives and drug addiction programs within housing projects -- was credited with helping reduce drug use in public housing by up to 44 percent in some communities. Bush ended the program last year. Public housing advocates, devastated by the loss, predict that crime rates will begin to rise again as a result.

The One Strike rule was created by the Department of Housing and Urban Development during the Clinton administration to curb drugs and crime in public housing. It was to be a tool, says Jon Gresley, executive director of the Oakland Housing Authority, to give residents like Lark authority in their own families, and power in their housing projects. But enforcement of the rule demands relentless vigilance and enormous responsibility. It requires grandparents taking care of grandchildren, who constitute many of the projects' residents, to regard their own family members with panicked suspicion; to monitor their activities, even when they are not at home. And if the grandparents detect bad behavior, they have to stop it, or lose their apartments.

This was the dilemma of plaintiffs in the Supreme Court case. Willie Lee and Barbara Hill were threatened with eviction when their grandchildren -- first-time offenders -- were caught smoking marijuana in the parking lot of their Oakland, Calif., apartments. Grandmother Pearlie Rucker came to the brink of eviction because her developmentally disabled daughter was caught smoking crack three blocks from Rucker's apartment. Disabled senior Herman Walker is in trouble because his caretaker secretly brought crack into Walker's home. (As of this week, only Walker still faces eviction. The others have been given another chance.)

The fate of these elderly people is frightening to their peers, who aren't just afraid of eviction, but wary of the estrangement that the burden of household law enforcement may bring. The One Strike rule pits love against reason: If the surrogate parents of abandoned kids must now view the children as potential liabilities, they may not have the courage or ability to take them in at all.

Says Anne Omura, attorney with the Eviction Defense Fund in Oakland, and lawyer for some of the plaintiffs in the Supreme Court case, "Realistically, it's going to stymie alternative families, because you can be punished and held accountable for the acts of another person. It chills the freedom of association with their own family members.

"You may love your grandson and want to take him out of a bad lifestyle," she adds, "but if he screws up once you will lose your home. I just hope family members don't have to file restraining orders against their own families to save their homes."

According to data collected by the Department of Housing and Urban Development, there are some 3 million people living in 1.2 million public housing units: 360,000 are elderly and 1 million are children. HUD's statistics say that roughly 25,000 minors are being raised by their grandparents within public housing, but these numbers are considered unreliable, thanks to the countless public housing residents who underreport the number of family members living with them. More data can be gleaned from the U.S. Census, which reports that 2,354,121 grandparents nationwide are raising their grandchildren; about 60 percent of those are single grandmothers, and of these families, almost two-thirds are living in poverty.

Gresley, of the Oakland Housing Authority, says families headed by grandparents constitute a "very significant" percentage of the total families in his projects. He suggests that the same is probably true around the country in communities where drugs -- in particular crack -- have destroyed families. Certainly, grandparent-run families are common enough that in some cities, entire housing programs have been created to cope with the trend. The GrandFamilies home in Boston, for example, is a much-lauded program that gives homes to 26 grandparents who are raising their grandchildren. The program, created by the mayor's office in conjunction with Boston Aging Concerns -- Young and Old United, has proved so popular that its organizers are opening a second, 16-unit home, and hope to expand across the country.

These programs attempt to address the overwhelming challenges faced by elderly people raising kids who are 40 to 50 years younger than they are, challenges that are compounded in communities plagued by poverty and drug use. Founders of the dedicated programs suggest that within the confines of the community, housing projects in particular, grandparents don't need more responsibility or higher stakes for discipline, they need backup.

"I know some grandparents have a hard time laying down the rules with the kids sometimes," says Elmer Eubanks, executive director of Boston Aging Concerns. "How much can they control a 13-year-old if they start being disrespectful? We need to look for resources to help them learn to deal with the kids; they want to spoil them as grandparents, not be the disciplinarian again."

Adds Omura of the Eviction Defense Center, "You have an elderly grandmother just trying to do right by a grandkid, but is she really supposed to be following him to school and back, going to the basketball courts with him?" This is a task, she points out, that younger adults, rich or poor, have a hard time pulling off with their children, and when they fail, unless they live in public housing, they don't lose the roof over their heads.

An even thornier problem for grandparents like Lark who take in the grandchildren of addicted parents is the behavior of their own adult children, many of whom want to visit or just hang around for a meal and a temporary place to sleep. These visitors bring the risk of eviction if they show up on drugs, or buy drugs on the property, or get in a fight there. In order to keep her apartment, Lark had to prohibit her drug-addicted daughter from visiting her own children: When her daughter showed up at her door, Lark would only let her speak to the kids through a locked iron grille. To live by the letter of the One Strike law, Lark shouldn't even have opened the door to her daughter.

Essentially, she can't win. If she doesn't come down like a cop, she could lose her apartment. But by taking a hard line, she could drive her daughter further away, and earn an 8-year-old's confused resentment.

There are no exact statistics that indicate how many public housing residents have family members or close friends who have struggled with drugs or been in trouble with the law, but common sense dictates that the number is high. According to HUD's statistics, in the first six months of 1999 alone, 559 public housing authorities (out of more than 3,200) reported a total of 79,212 crimes, which covered offenses from homicide to burglary to rape.

This would mean that the odds are excellent that a majority of all housing project residents -- at one point or another, with or without their knowledge -- have played host to someone who did something illegal on or near the property. Lark says she sees drug dealers in her yard every day. To keep them from doing something that could lead to her eviction feels about as easy as winning the lottery.

Public housing authorities argue that the One Strike law is not as Draconian as it sounds. They say that the Supreme Court ruling does little more than allow housing authorities to keep their properties safe. Sunia Zaterman, executive director of the Council of Large Public Housing Authorities, believes that the powers that be can be relied upon to take mitigating circumstances into consideration.

"It's a false notion that authorities are proceeding with eviction at the drop of the hat," she says. "They see whether it's appropriate or not." She contends that housing authorities will not order an eviction before considering whether a crime is a first-time offense or a minor infraction, and whether the family in questions is headed by a diligent grandma or a crack-addicted mother.

Yet the cases ultimately considered by the Supreme Court demonstrate that housing authorities aren't always forgiving of minor infractions. Lee and Hill, for example, faced eviction the first time their grandsons were caught smoking pot -- an infraction, incidentally, that often merits only a fine. And in a supporting brief to the Supreme Court case, the Brennan Center for Justice cited eight examples of frivolous One Strike evictions, including a grandmother who was evicted because her mentally retarded granddaughter threw her baby out the window and a woman who was evicted because her boyfriend broke into her home and beat her up.

Kimberly Preston of Crescent Park has a similar story. She faced eviction two years ago after her 16-year-old son was put in juvenile hall for two days. He had been standing outside with a group of teenage boys in the projects when the police arrived and began looking for drugs. Preston says that the police found no drugs on her son, but they did find a wad of cash in his pocket -- money, Preston contends, that she had just given him to go shopping. Nearby, however, the police found a ball of crack in the ivy. While her son was never charged with a crime, Preston was told to move a few weeks later. With the assistance of the Eviction Defense Fund, she battled the eviction and eventually won.

"They try to put you out on anything!" she complains. "It was the first time they'd ever talked to me." She says the authorities are focusing on the wrong people, and should be nailing the itinerant dealers who hang out in Crescent Park instead of putting out employed mothers like herself: "The whole place is infested: killings, murders, all kinds of things. They call this the G Lot -- the gangster lot."

Preston and other housing project residents concede that One Strike has had some measurable impact. Drug use and crime have been reduced, says Preston, as the most egregious families have been booted out of the buildings. But, she says, the same effect could be achieved by the police, if they would do their jobs. And eviction doesn't remove a drug dealer from the premises, say Preston and other residents. Even if they no longer live there, they still hang around. Within the 14 units in her courtyard, says Preston, four mothers have been evicted because of their children's drugs and crime. And yet even after their families were evicted, the kids that were making trouble are still hanging around the projects, she claims.

"Even though they put these people out, I still see them roaming around: They have a nice place to do their business," she says. "It's ridiculous. Lock their ass up and put them away and then you won't have a problem. But if you just put the family out, the kids still come back. They don't care."

One goal of the One Strike law was to give some teeth to parental discipline, to inflict the fear of eviction on kids tempted to break the law. As Gresley describes it, "Youth respond to having rules and discipline and a consistent set of expectations; perhaps having it clear what the housing authority will tolerate will assist grandparents in controlling their grandkids." But, as Preston points out, the penalty seems to have more of an impact of adults than kids. What is needed more than punishment is distraction, she says.

Eubanks says that the main task of GrandFamilies has been to provide grandparent-helmed families with diversions for aimless teenagers. "We need to keep the kids occupied with activities and provide respite services for grandparents who can't take the kids out," he says. "We need more supportive programs and after-school activities; homework centers and tutorials -- activities that will let the kids learn rather than just being punitive. If the grandparents end up on the street, the kids end up in foster care."

But the dearth of funded activities, many of them part of the Public Housing Drug Elimination Program that Bush killed last year, means that the majority of kids hanging around the projects have few alternatives. Meanwhile, more and more families, driven by rising rents, are packing into the subsidized apartments, further increasing the odds that evictions will start to rise. Sunia Zaterman says that in many cities, particularly large ones, the housing markets are so tight that there is considerable amount of doubling up. Much of it, says Zaterman, is unnoticed by housing authorities.

"People that can't afford market rent and have nowhere else to go often move in with family members," she says. "You've got people in the household not on the lease, or not directly members of the family, and not allowed to live there."

Housing projects represent shelter of the last resort. The alternative is usually the street. When families in public housing take in family members, many of them troubled or in trouble, they do so as an act of kindness. And if the reward for this act of charity is a greater threat of eviction, many more people will be on the street -- forced there because their relatives can't afford the risk of taking them in. Ultimately, say advocates for residents of public housing, this will cost more money and destroy families. Surely, for an administration that favors less spending and stronger family values, this is not a good thing.

Is it possible for any parents, whether they live in a gated community or a housing project, to completely control their kids or their kids' friends, effectively stopping them from trying drugs or participating in any illegal behavior? Says Jim Grow, an attorney at the National Housing Law Project, "This is everybody's life in modern America. Yes, you can do what you can do as a parent to try to educate your children and teach them to be responsible about drugs and criminal activity. But we don't always succeed as parents."

Just ask Jeb and George Bush. If the actions of their children had been subject to the One Strike law, much of the Bush family would be homeless. And maybe they should be. After all, they live, for the moment, in public housing.

Shares