Even as he remains holed up in his crumbling Ramallah compound, hungry, dirty, besieged, Yasser Arafat has enjoyed a good week. His meeting with Secretary of State Colin Powell on Sunday yielded little, but Powell is expected to return to see the Palestinian leader on Tuesday. And Israel's supposed concession on Sunday -- calling for an international peace conference, but without Arafat -- was roundly rejected by Arabs and Palestinians, who said there could be no peace talks without the Palestinian Authority chairman.

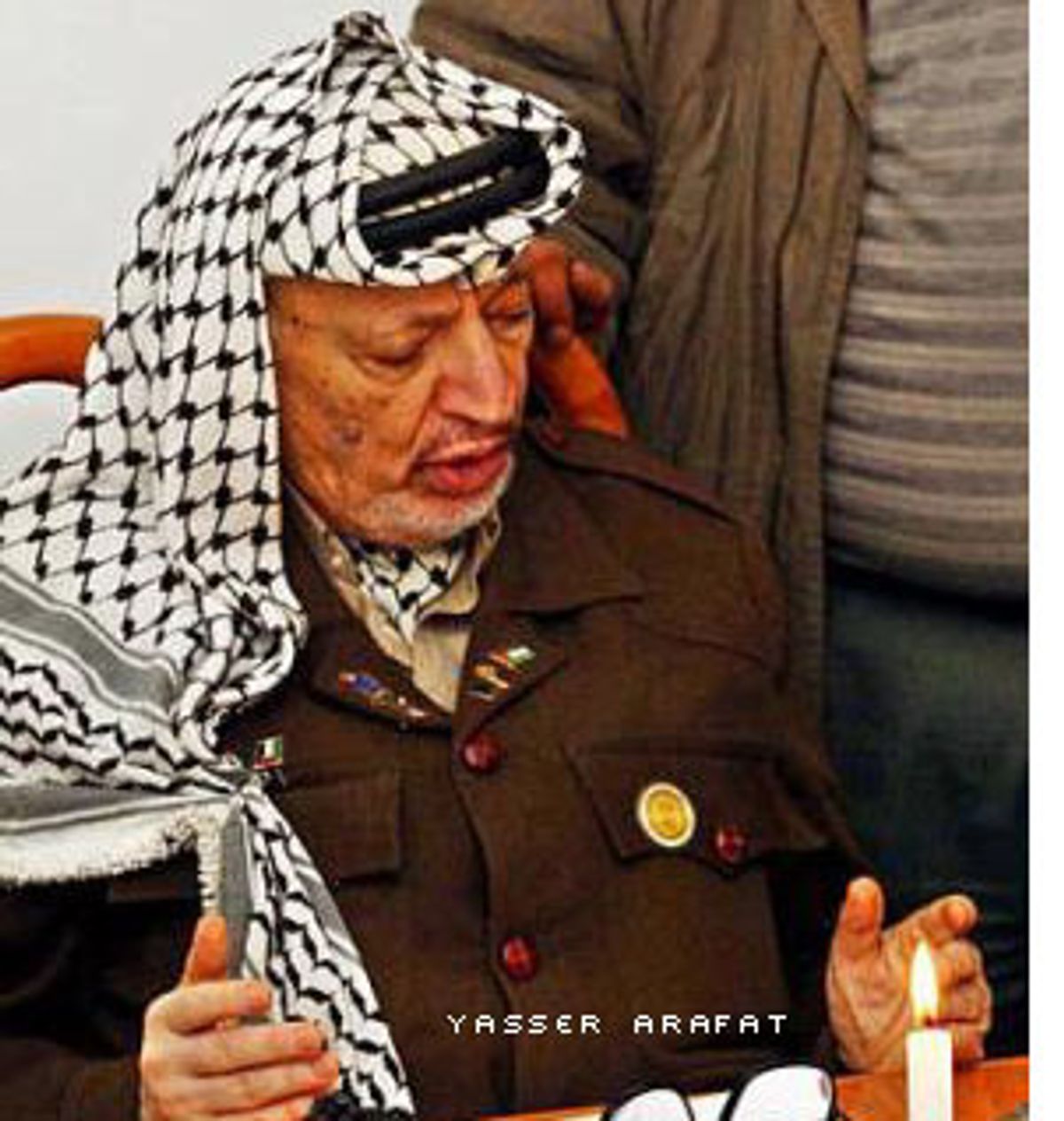

"People have no choice but to rally behind Arafat now," said one West Bank man, speaking on condition of anonymity. Before Israel isolated him at his Ramallah compound, Arafat's approval rating was hovering around 20 percent in polls cited by the BBC and others. But now, pictures of the Palestinian leader trapped in his headquarters, working by candlelight, are circling the globe, bringing Arafat his greatest glory since Oslo. In fact, Israel's military campaign has so far had the exact opposite of its desired political outcome, which was to isolate and discredit Arafat. Instead of clearing the way for independent leadership to emerge, as Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon and President Bush both publicly said would be desirable, Israel's military sweep has reinstituted Arafat as the ultimate symbol of Palestinian nationalism, and America's lone Palestinian partner in peace.

This is, of course, not the first time Israel has helped elevate the status of the Palestinian leader. Since the beginning of the Oslo peace process, Washington and Israel's desire to deal with a Palestinian strongman -- who could control his population, keep a tight lid on popular dissatisfaction in the West Bank and Gaza and deliver on promises to the West -- has consistently salvaged Arafat's standing with his people, despite his increasingly repressive ways. The start of the early 1990s peace process, for instance, was marked by Israel and the U.S. abandoning talks with leading West Bank independents and moderates, to embark on secret talks with the exiled PLO chairman instead. Former Israeli Prime Minister Itzhak Rabin used to defend shaking the hand of a man most Israelis considered a terrorist by arguing that only Arafat could handle Hamas and other troublemakers without worrying about "the Supreme Court and [the human rights organization] B'Tselem."

Even today, pick up any glossy newsmagazine and you are likely to come across a discussion on the possible successors to head the Palestinian Authority after Arafat. The fact that Americans and Israelis have traditionally discussed Palestinian politics as a "succession question," rather than a democratic process, is telling. The quest for a Palestinian moderate has always focused on the strongmen around Arafat -- his deputies, cronies and security chiefs. Most notable among these were West Bank security czar Jabril Rajoub, Gaza security chief Mohammed Dahlan, the secretary general of the PLO Mohammed Abbas (alias Abu Mazen) and Ahmed Qureia (aka Abu Ala), the speaker of the Palestinian Parliament. Some have identified Fatah commander Marwan Barghouthi, arrested by Israel Monday, as another possible Arafat successor, but he was probably too radical to ever have gained the U.S. support a Palestinian leader requires. But all of Arafat's possible successors have been his protigis, men who preside over various Palestinian apparatchiks and owe their position to their direct association with Arafat and his organization, Fatah. Never mind that large sectors of the Palestinian public had become disenchanted with the corruption and the despotism of Arafat's government, that human rights abuses had increased under his security structure, that journalists and opponents complained of daily infringements on free speech, that corruption by P.A. officials is legendary. Arafat's henchmen have always been hot, hot, hot in Washington.

But the quest to anoint one of them Arafat's successor has so far failed. American favorite Jabril Rajoub, the 48-year-old Palestinian security chief, found himself caught up in the latest military sweep, his security compound stormed by Israelis, his men arrested. Rajoub's story is illuminating. Like an ambitious young Roman notable in the court of Julius Caesar, Rajoub rose among peers and allies in the West Bank over the last few years of Palestinian self-rule to emerge as a leading contender to replace Arafat. Among the myriad security and intelligence units of the burgeoning Palestinian administration, Rajoub's Preventive Security Service was arguably the best-equipped and the least tainted by involvement with attacks on Israelis. With great ties to Israel's security brass and the Central Intelligence Agency, and the leader of 10,000 armed loyalists, for a time Rajoub seemed Israel and Washington's best hope in their search for a Palestinian Karzai.

Americans helped build and finance Rajoub's police network -- a key element of CIA director George Tenet's cease-fire plan -- as the Palestinian Authority's primary channel to exert control over the population and implement counterterrorism efforts. In Monday's disparaging New York Times column, William Safire called him "Tenet's Palestinian," and suggested the CIA director had been fooled by Rajoub's supposed moderation. But even many Israelis whispered discreetly in Washington corridors that Rajoub was a "moderate" they could do business with. He spoke good English and Hebrew, thanks to doing some time in Israeli prisons back in the pre-Oslo days, and had good friends in important places in Jerusalem and Washington. While Israel has been targeting Arafat's police force and his top security brass over the last year, Rajoub's forces were spared. He was rumored to have been taken on a regional tour of the Gulf countries and Jordan by the CIA, being touted as a future Palestinian leader.

It mattered little to his American sponsors that Rajoub, like Arafat, was hardly a man of democratic instincts. Driving a Mercedes and living well like most top officials, he also got his share of the Palestinian public's contempt for corruption within the P.A. Rajoub was also disliked by the intellectuals who saw Arafat's Fatah crowd as a group of thugs who returned from exile in Tunisia in the '90s to run the country. (Palestinians like to joke, "We were once under Israeli occupation; now we live under the Tunisians' occupation.") But unlike the Palestinian leader, he lacked charisma, and also unlike Arafat, he was willing to cooperate with the Israeli security brass and publicly condemn suicide attacks. Gradually he became unpopular among Palestinians due to the perception that he was too closely affiliated with Israel.

All that of course came to an end April 2, when Israel's military sweep of Palestinian towns and camps targeted Rajoub's CIA-financed Ramallah headquarters to arrest those inside. Tanks closed in amid Israeli allegations that the building was sheltering fugitives, including a dozen Hamas prisoners. The ostentatious marble and wood paneling inside was destroyed by shelling, along with Rajoub's office (where the police chief reportedly kept a framed picture of George Tenet).

But the Israelis were not just after those militants. Rajoub had clearly fallen from grace in some deeper way. An Israeli spokesman accused the burly Palestinian chief of sending two suicide bombers to Jerusalem in March. Officials claimed that Rajoub -- yielding to pressure from Arafat and hoping to get ahead in the succession struggle waged by Arafat's deputies -- had recently changed his position regarding the use of violence. Israel, one spokesman told the media, planned to "isolate" Rajoub in the same way it did Arafat.

But the security chief was not inside his besieged compound, so he could not be isolated there. In the subsequent showdown, the Israeli Defense Forces launched a serious attack on the complex using heavy machine guns and other weapons. "Surrender is not in our culture," a defiant Rajoub told reporters in Ramallah over the phone. But that same afternoon, the standoff came to an end when the CIA and Rajoub himself negotiated the surrender of more than 200 of his men. He is said to be in Ramallah.

Hamas, which already distrusted Rajoub, immediately issued leaflets calling the security chief a traitor. Arafat's close advisors told the media they had no idea that surrender was in the works, hinting that Rajoub had cooperated with the Israelis on his own. Arafat, long uneasy about his lieutenant's rising prominence in the West, remained silent. (In February, the increasingly volatile Arafat reportedly pulled a gun on Rajoub, accusing him of conspiring with the United States and Israel to take over the Palestinian Authority.) Meanwhile, Israelis say they have captured evidence at Rajoub's compound that he sold them out and collaborated with suicide bombers. Now, although he has eluded both Israeli arrest and Palestinian reprisal, Rajoub is hardly a contender to replace Arafat.

But no one has emerged in his place. "I don't think, I don't want to think, that Rajoub was ever thought of as a top man but the strong man behind the [next] leader," a prominent Palestinian businessman said in a phone interview. "To have him propped up as a leader would have been an insult to us Palestinians. He's now pretty discredited in any case." In some scenarios, Rajoub would have been a No. 2 to parliament speaker Ahmed Qureia (aka Abu Ala), but Ala too has gravitated closer to Arafat in the current crisis, as has Mahmoud Abbas, a key figure in the Oslo process.

Rajoub's Gaza counterpart, the dashing Preventive Security Chief Mohammed Dahlan, has likewise lost immensely in the eyes of Palestinians and Israelis alike, with Palestinians resenting him for working with Israelis, and Israelis feeling he betrayed their trust by siding with Arafat at the last minute and backing attacks against Israel. Sharon's inner circle has turned against all of them, and they have clustered loyally around Arafat.

It may seem too pie in the sky, at this time of military crisis, to talk about Palestinian democracy. But there are many Palestinians and Israelis alike who believe the current crisis can be traced to the failure of Israel and the U.S. to back a democratic government in the territories.

"Israelis did not care about democracy and nor did we," said a former U.S. official, looking back. "There was almost a level of racism [in the decision to court Arafat's men] that Palestinians, as all Arabs, aren't entitled to democracy. What they really need is someone really strong." Democracy was unnecessary, the reasoning went; Rajoub had all the guns needed to succeed Arafat.

And while the West poured millions of dollars into democracy and civil society initiatives in the West Bank and Gaza, the P.A.'s moves to bypass the Palestinian Legislative Council, arrest dissident journalists and opponents, and stall elections met little outcry from Western governments. Eager to write the final chapter on the Middle East as a success story, Europeans were happy to overlook the mismanagement of millions of dollars and Arafat's repression here and there. Elections were held two years after Arafat moved back from exile in 1994. In 1999, only 28 percent of Palestinians believed that their political system was headed toward a democratic form of governance that protected human rights, according to a poll by the independent research house Center for Palestinian Research and Studies.

A month ago, when asked why the U.S. was not pushing for elections in the Palestinian areas, a State Department official explained to me how inconvenient elections would be right now, although Arafat's electoral mandate expired in 1999. He pointed out that there were no clear successors and Hamas was gaining popularity. "Although conceivably, some time in the future, it could happen," the American official said unconvincingly.

"I am so ashamed as an Israeli," said Yigal Carmon, who heads the Washington-based Middle East Media Research Institute. "People said there wasn't any alternative, but just because we didn't know people didn't mean they did not exist. We're not here to advance democracy, people were saying. Arafat reluctantly held elections, quickly set up nine security organizations, and was given the authority to run people's lives."

Over the last few months, an article by Palestinian intellectual Edward Said, "A New Current in Palestine," announcing the birth of a "new secular nationalist current" led by well-known intellectuals, has been making the rounds in cyberspace. But such a movement is likely to back down in the face of Arafat's increasing prominence since the Israeli military sweep.

Unhappy with Arafat's rule and weary of the fighting, a large chunk of the Palestinian society remains moderate, eager for a settlement and hungry for democracy. And yet the Palestinian "silent majority" does not seem to feature in Washington's radar at the moment.

"Sure, what is needed is somebody with both stature and charisma," said the Palestinian businessman. "But the question should no longer be who comes after Arafat, but what type of a system Palestinians could establish to move forward. Otherwise, there is no point in appointing someone."

Shares