In March 1998, two months after the Monica Lewinsky maelstrom had begun convulsing the political and media establishments, I was invited along with two other Salon editors and our Washington reporter to attend an afternoon reception at the White House. The gathering consisted mainly of a group of young White House fellows; I think the Salon contingent was invited out of curiosity about this maverick West Coast Web site that had begun breaking stories on the Whitewater investigation and its ties to the secretive anti-Clinton operation known as the Arkansas Project. The idle chit-chat in the room where FDR had delivered his fireside chats suddenly paused as Hillary Clinton breezed in, followed shortly after by her husband and his entourage. The president worked his way through the room and when he got to us, he immediately began discussing Salon's allegations that Ken Starr's chief Whitewater witness, crooked Arkansas judge David Hale, had received cash payments and legal assistance from the Clinton-haters who financed and ran the Arkansas Project. Clinton, quite understandably, wanted to know, "When is the rest of the press going to pick up on this stuff?"

After Clinton moved on, I drifted over to a knot of people gathered around the first lady. Several weeks before, she had elicited scorn and derision from the media with her comments about a "vast right-wing conspiracy" arrayed against her husband. Her small audience that day, however, was more sympathetic. After all, Salon was in the process of documenting the conspiracy, which if not "vast" was certainly extensive -- stretching literally from the swamps of Arkansas to the top of the GOP -- well-coordinated and financed, and relentless in pursuit of its prey. She talked with feeling about how difficult it was to withstand the intense political and media pressures, which had reached a frenzied level. And then she told us something that I don't believe she had said in public before, or has since: "When we were getting ready to announce for the 1992 campaign, the Bush people said to us, 'Don't run this time -- wait four years and you'll have a free pass. If you do run, we'll destroy you.' And I said to Bill, 'What are they talking about -- how could they do that?' And now we're finding out."

The Washington commentariat would have had another field day with these remarks -- they would have cited the story as one more example of Hillary's inclination toward political melodrama and exaggeration. But even though I didn't get the chance to ask her more questions, I believed the story and still do. It came back to me as I was reading David Brock's stunning new memoir of his days as a right-wing character assassin, "Blinded by the Right." There has been a dark and ruthless side to modern Republican politics ever since the Roosevelts were reviled as Jews and black-lovers and Joe McCarthy and Richard Nixon worked their poisonous craft. But in the last decade, as Brock documents in often repulsive detail, this virulent conservatism -- which one of its more cunning practitioners, Lee Atwater, famously referred to as "extra-chromosome" Republicanism when even he grew exasperated with it -- has taken full control of the party.

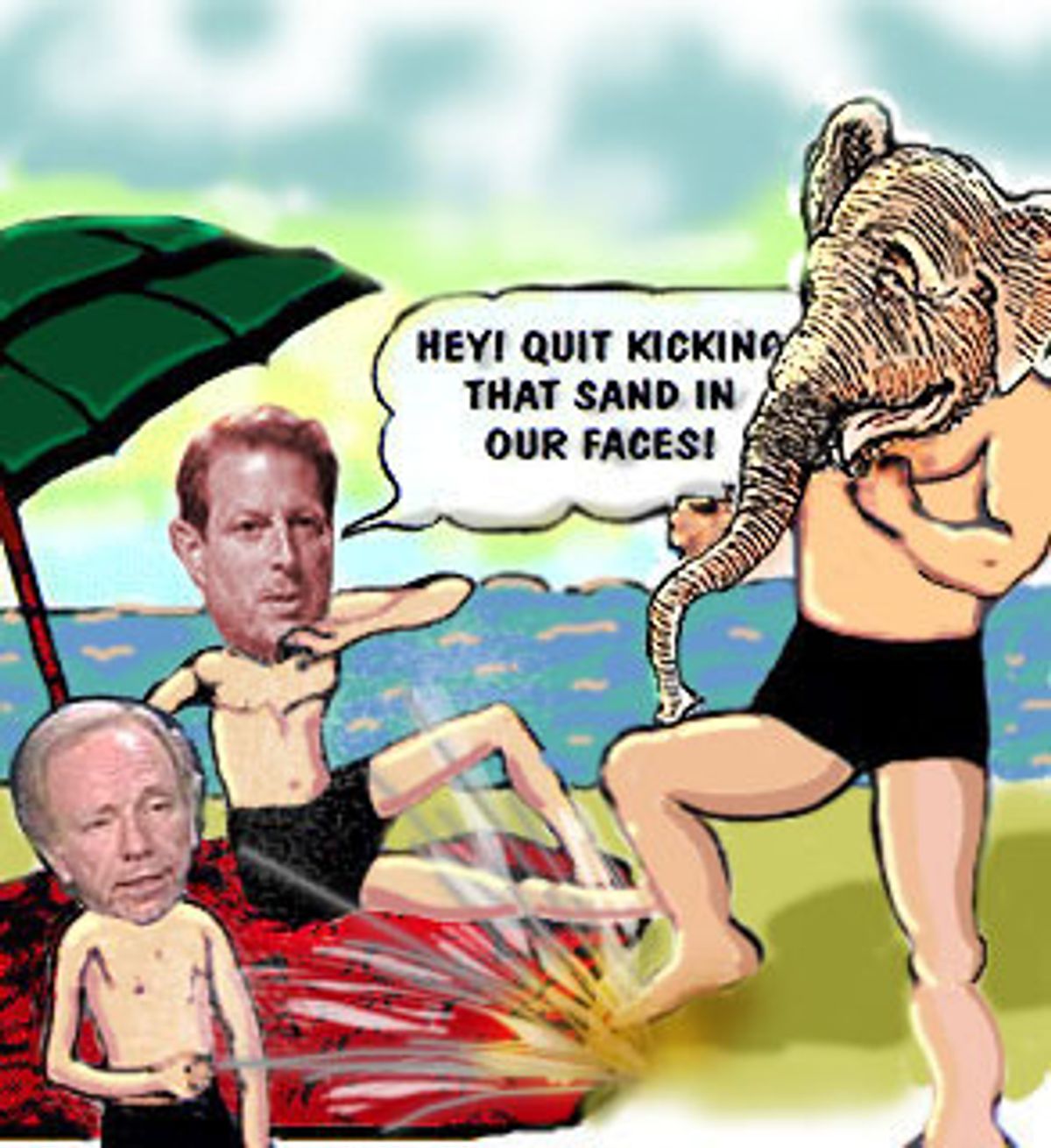

Confronted with these relentless opponents, the Democrats have all too often caved in. When Al Gore blasted Bush last week, it was a painful reminder of what he and Joe Lieberman didn't do in Florida, when GOP bullies simply ripped the presidency out of their hands. Until the Democrats learn to fight for what they believe in as tenaciously as their opponents, they will never be an effective political force.

Brock paints a baroque portrait of the conservative movement and its GOP Jacobins, including the paranoid and reclusive billionaire Richard Mellon Scaife, who, through generous disbursements of his fortune (including to the American Spectator magazine's Arkansas Project), was able to make his hatreds and delusions those of the party; the movement's roly-poly Lenin, Newt Gingrich, who when not inveighing against the moral rot of 1960s demon seeds like Bill Clinton was pursuing the illicit delights offered by a young congressional aide; Ted Olson, the distinguished barrister and current Solicitor General who was not above penning anonymous smears of Clinton, soiling himself in the funky loam of the Arkansas Project and whose late wife, Barbara, once led a bizarre raiding party that, in search of more White House "Travelgate" dirt (remember that gravely important issue the GOP and Washington media so dutifully rubbed in the Republic's face?), trespassed onto the gated grounds of a private Georgetown compound to peep through the windows of a White House aide; the esteemed Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas, who in his never-ending campaign to discredit Anita Hill and her supporters, leaked to Brock embarrassing personal information about a former female colleague that had been sealed in divorce court documents; C. Boyden Gray, the former Bush White House counsel whose attempt to pull off an "October surprise" against Clinton in 1992 would help spark the serpentine Whitewater investigation and who in graceful defeat kept urging Brock to pursue Vincent Foster murder tales and other gothic Clinton lore.

And these were the high-profile guys! The bit players in the conservative revolution, as described by Brock, were an even seamier lot. Lonely, fat, horny lawyers who brooded bitterly over Clinton's easy way with women; sleaze-peddling Arkansas troopers out to make a dirty buck; upright, gay-bashing conservatives who tried to bed Brock -- and then there's filthy-minded Lucianne Goldberg, who secured her footnote in American political history as Linda Tripp's accomplice, delightedly hawking a story to the equally spiteful New York Press about Clinton "finger-fucking" his daughter Chelsea.

There was simply nothing that these people were incapable of saying or doing to advance their political agenda. They shamelessly and self-righteously crossed dozens of lines that marked what once were the acceptable bounds of political battle. Everything was permissible, the Leninist Gingrich told them, because this was a war to the finish. The Clinton presidency was illegitimate, "a cultural coup d'état," they informed the country -- this from the same people who denounced Democrats for not "moving on" after George W. Bush was handed the presidential election by a stacked Supreme Court.

Brock's book, which must rank as the most sickening -- and entertaining -- exploration of the underside of American politics ever written, has rocketed up the bestseller lists. But the book has, for the most part, prompted an eloquent silence from Brock's former allies in the conservative propaganda wars -- Clarence Thomas, Ted Olson, Bill Kristol, Rush Limbaugh, Laura Ingraham, Ann Coulter, John Fund and so on. Some conservatives have tried to airily dismiss the book as the work of an unreliable observer -- "He says he lied about Anita Hill and Troopergate, how can we believe him now?" is the standard line. (To be fair, Salon's Kerry Lauerman asked the same question. ) Of course, Brock was lying on behalf of the conservative cause back then -- and despite how quickly the media dismantled much of his American Spectator reporting (and how some right-wing colleagues personally knew Brock's anti-Clinton charges were at the very least shaky), none of these conservatives questioned his veracity in those days. It's only now, with "Blinded by the Right," that conservatives have grown a sense of journalistic skepticism when it comes to Brock.

The fact is, none of Brock's most damning allegations in "Blinded by the Right" have been knocked down by the media or his conservative critics. In a letter to the New York Times Book Review on Sunday, Brock's old boss at the American Spectator, R. Emmett Tyrrell, attempted to salvage the shredded Troopergate story as well as defend Ted Olson against the Brock charge that he "encouraged conjecture that [Clinton counsel Vincent] Foster might have been murdered." But since Tyrrell, a clownish self-promoter and Clinton conspiracy freak whose own attempts at journalism never even reached Brock's old standards, is the conveyor of this rebuttal, it's safe to dismiss it as self-serving twaddle. With the exception of David Horowitz, who strongly denies Brock's claim that he made homophobic comments to a book editor he did not know was gay, no one has plausibly challenged even Brock's minor charges.

Yes, there is something disturbing about the way Brock writes of his consistently unheeded pangs of conscience -- which began plaguing him as early as his Troopergate story for the American Spectator in 1993, and which Bill Kristol, to his credit, was the only conservative to advise Brock not to publish. "Bill told me that conservatives should focus on substantive disagreements with the Clinton administration, and he warned that the piece would stigmatize me as a tabloid journalist." (Unfortunately, Kristol would abandon this principled position in the following years as the GOP escalated its personal assault on Clinton.) But if it took too long for the scales to fall from Brock's eyes, he is brutally honest about the reasons: An ambitious young journalist whose gay sexuality had estranged him from his conservative parents, he grew intoxicated with the sense of moral righteousness -- and the creature comforts (a sleek black Mercedes and a posh Georgetown address among them) -- that his role as the conservative movement's Bob Woodward afforded him. "I bought it all because I wanted to. War for war's sake was really the only way I knew since coming to Washington ... I also had career considerations."

What matters most is that in the end, Brock did the right thing, beginning with his refusal to smear Hillary Clinton in his 1996 book about her (which began to fracture his relationship with the conservative crusade) and continuing with his apologies to Anita Hill and others whose characters he had assassinated, all the way to "Blinded by the Right." His former comrades on the right accuse him of mercenary motives, but as Brock responded last Saturday on Tim Russert's CNBC show, it's certainly not a "clever career move to admit to everything I did. Most people in my profession are loath to admit their mistakes."

One of the most repellent aspects of Brock's book is his reminder of how the right-wing sleaze campaign eventually succeeded in dictating mainstream news coverage. The most avid bulldog on the Clinton sex beat was not an American Spectator hack, of course, but Newsweek's Michael Isikoff. Brock reports that while he was researching his book "The Seduction of Hillary Clinton," Isikoff passed on to him a number of Clinton sex tales that his Newsweek editors decided weren't up to their standards, in the apparent hope that they would meet Brock's less exacting ones (they didn't).

Even the New York Times played an instrumental role in the criminalizing of the Clinton administration, with Jeff Gerth's seminal -- and specious -- reports on Whitewater. Gerth's principal blunder was allowing himself to get taken in by the hucksters and con men who worked Arkansas' anti-Clinton carny show. Brock, himself a frequent visitor to these gaudy peddlers of political dirt, writes that it was Sheffield Nelson, the grandaddy of Clinton smear artists, who put Gerth in touch with his Whitewater source James McDougal. Speaking of being loath to admit their mistakes, a decade later Gerth and the Times' editorial mandarins have yet to concede the bankruptcy of their investment in the Whitewater story, even after two relentless and politically malicious special prosecutors failed to find any proof of crimes on the part of the Clintons. The Times' editorial excellence is matched only by its breathtaking arrogance. By now it's abundantly clear that it was the scrappy, independent reporting of dogged journalists like Murray Waas in Salon and Joe Conason in Salon and the New York Observer that had it right about Ken Starr and Whitewater -- not the Times or the Washington Post.

Sheffield Nelson, who had lost a bitter governor's race against Clinton in 1990, was also behind the peddling of the Juanita Broaddrick rape charge against Clinton. While researching his Hillary Clinton book, Brock worked tirelessly to corroborate the story. But even he had to finally conclude that "Juanita came up with the rape claim ... after having consensual sex with Clinton ... to get herself out of trouble with her boyfriend (and later husband) Dave Broaddrick." But in a familiar pattern, the Wall Street Journal's editorial page injected the poisonous story into the legitimate news stream and in the subsequent media feeding frenzy, NBC aired a Lisa Myers interview with Broaddrick that its producers had formerly considered too sketchy to broadcast.

No news organization sullied itself more during the Clinton years than the Wall Street Journal. The tabloidization of the Journal's editorial pages in the service of the get-Clinton propaganda campaign is one of the great scandals of American journalism. It was one thing for publisher Peter Kann, long before Clinton, to encourage editorial czar Robert Bartley to turn his pages into a forum for aggressive conservatism. It was quite another to allow Bartley and his fellow zealots to publish every crackpot defamation of the Clintons that excreted its way into the right's imagination. They loudly and repeatedly suggested that White House counsel Vincent Foster had been murdered (perhaps, Brock surmises, to deflect attention from their own role in his death; Foster, clearly ill equipped for Washington's increasingly savage climate, pointed to "WSJ editors [who] lie without consequence" in his suicide note). They brooded obsessively about "mysterious Mena," the Arkansas airport where Clinton and his cronies allegedly trafficked in drugs and where "Clinton death squads" murdered two teenagers to cover up their nefarious business. It is unclear whether Bartley, who emerges as one of the strangest fishes in Brock's weird aquarium, really believed any of this Clinton frothing or whether he had simply sold his journalistic soul to the far right. But the more important question is why the top editors and executives of the Journal allowed him to get away with it. Bartley no longer runs the Journal's opinion section; he's been kicked up the corporate stairs. But in his golden years he has been awarded his very own column, where recently he took a typically wild swipe at Brock as "the John Walker Lindh of contemporary conservatism." Like his fellow right-wing propagandists, Bartley could offer nothing of substance to rebut Brock.

At the White House reception I attended, Clinton remarked, "Maybe I'll be remembered as the president who took the poison out of American politics." This theory has since been embraced by a number of political commentators, including the New York Times' keen-eyed Frank Rich, who characterized Brock's memoir as a chronicle of a faded, pre-Sept. 11 era. But this, unfortunately, is wishful thinking. The Old Testament fervor that inflamed the GOP and the conservative movement throughout the Clinton era is still very much alive, from the attack ads on Tom Daschle comparing him to Saddam Hussein for his opposition to Alaska oil drilling to John Ashcroft's suggestion that anyone who opposed his attempts to shortcut the Constitution was on the side of terrorism. The excesses of the current conservative crusade may not match the outrages documented by Brock -- but only because Bill Clinton, or any other Democrat, does not occupy the White House. And it's not necessary for the GOP to go scorched-earth when, ever since Sept. 11, the Democrats have obligingly turned themselves into "war wimps," in Rich's phrase.

But now that even chronically cautious Al Gore has begun raising his voice against the Bush administration, it seems that political life might be coming back in America. This means the holy warriors of the right will once again be on the march, eager to put any moral or political enemy (generally one and the same) to the torch. With the Bush political operation run by the win-at-any-cost heirs of Lee Atwater, and the GOP ranks filled by passionate Christian activists, the Republican cause still carries the air of a religious war, even without revolutionary prophets like the disgraced Newt Gingrich (who undoutedly is plotting a Nixonian resurrection).

The question that arises for any liberal or moderate, especially after reading Brock's book, is how do you fight successfully against this kind of political ruthlessness -- without doing even more damage to democracy. Can you counter the GOP's ferocity by attacking opponents with equal ferocity on the issues and not on their human flaws?

Politics is a blood sport, but it doesn't have to be so savage that it subverts our political system, as Republican zealots like Bob Barr, Ted Olson and Robert Bork did when they began intriguing for Clinton's impeachment long before the nation heard of Monica Lewinsky. The problem for Democrats in recent decades is that the party's national standard bearers have often felt unsuited or uncomfortable at playing this sport, preferring governance over politics. But as John Kennedy observed, you can't have one without the other. When JFK was reminded of Eisenhower's disdain for the very word "politics," he responded, "I do have a great liking for the word 'politics.' It's the way a president gets things done." The Democratic candidates who obviously were more enamored of policy than politics proved to be losers -- Dukakis and Gore. The ones who thrived at the game of politics -- JFK, LBJ, Clinton -- have been the party's winners. And they knew how to play the game hard.

If John Ashcroft's team at the Justice Department can invoke the spirit of Bobby Kennedy in their war on terrorists (let's hope it's the spirit of Bobby's crackdown on organized crime, not his law-bending surveillance of Martin Luther King Jr.), Democrats should be calling on RFK's political fighting spirit. The feckless Gore recount battle in Florida cried out for the Kennedy brothers' brawling Irish machine. In fact, Democrats don't even have to conjure ghosts from as far back as Camelot. The party simply needs to clone a lot more Ragin' Cajuns. The single-minded commitment to framing the debate ("It's the economy, stupid") and the "instant response" counterpunching methods developed in James Carville's war room during the first Clinton campaign need to become part of the Democrats' DNA.

In their new book, "Buck Up, Suck Up ... And Come Back When You Foul Up," Carville and political partner Paul Begala argue that it's possible to employ "smash-mouth" tactics without resorting to the politics of personal destruction. Carville, who is married to Dick Cheney advisor Mary Matalin, must live out this "love your enemy, hate his (or her) ideas" sentiment every day of his life. But Republicans have long claimed it was the Democrats who kicked off the modern era of trash politics with their aggressive 1987 battle to block Robert Bork from the Supreme Court. So primal was this wound to the Republican psyche, that to this day whenever a conservative ideologue is rejected by the Senate, the GOP screams he's been "borked." The truth is, however, that while the liberal rhetoric against Bork sometimes grew inflamed, Bork was rejected on the basis of his legal record, which included opposition to the 1964 Civil Rights Act and Roe vs. Wade -- not because of any personal attacks. As the Washington Post's former Supreme Court correspondent John P. MacKenzie recently wrote, it was not "smear tactics or dirty tricks" that defeated Bork, it was his own "caustic writings and rigid philosophy." Bork's extremist pronouncements in recent years -- including his endorsement of a radical conservative call during the Clinton administration to reject the American "regime," including our system of government, as "morally illegitimate" -- demonstrate the wisdom of his rejection from the highest court. (Republicans have a better case for Democratic foul play in the Clarence Thomas hearings; Anita Hill undoubtedly told the truth, but Thomas' tacky personal behavior was irrelevant to the proceedings and should not have been used as a last-ditch gambit to derail him.)

The Republican attack machine has a habit of crying loudly -- and even calling for government intervention -- whenever their bullying brings them a punch in the nose. Take the case of Salon's 1998 story about Henry Hyde's adulterous past -- or as Hyde, in his late 40s at the time of the home-wrecking affair, preferred to call it, "his youthful indiscretion." By the time this story was brought to Salon by a friend of the family that was destroyed by Hyde's affair, it was clear that the Republican Party planned to bring impeachment charges against the president of the United States solely on the basis of a consensual sexual affair. There was nothing in Ken Starr's report to Congress about Whitewater; the machinery of government was convulsed over a blow job. (Yes, yes, it wasn't about sex, as the right wing never grew tired of telling us, it was about the law -- but the American people knew better.) Salon normally would not have published a sex exposé of this kind -- and indeed we have rejected many over the years. A public figure's consensual sex life should not determine his or her fitness for office. And that was the whole point -- in the hands of the GOP impeachment machine, private sexual behavior was about to determine the fate of the presidency. As many in the Washington and media establishments knew (but weren't telling the public) -- and as Brock's book would vividly detail -- the sexual hypocrisy on display in the impeachment frenzy was stunning. Hyde, who was to preside over the House impeachment hearings, and GOP leader Newt Gingrich, who vowed to use Monica Lewinsky in every speech he made, were just two of those in glass houses throwing stones at Clinton.

By publishing the Hyde story, Salon shattered the self-righteous hypocrisy that cloaked the impeachment crusade. And though Republicans like Tom DeLay denounced the Salon story as "an assault on the institution of Congress" and called for an FBI investigation to find out if the White House had leaked the information to us (they hadn't, as the media quickly determined), the public drew its own conclusions. Democrats and Republicans alike have human flaws -- that's no reason to paralyze the government, let's move on.

One of the key lessons of the 1990s witch hunts should be this: Keep sexual McCarthyism out of the political fray. Those who live by the sexual sword can die by it. Though Clinton's hope of detoxifying American politics might be too unrealistic, perhaps the attack dogs on the right can agree with this hard-won wisdom: If you dump your wife while she's in a cancer ward, if you desert your marriage for a young aide, if you expose yourself to park rangers, if you beat your girlfriend, if you advertise in swinger magazines for buff men to help enliven your marriage bed, if you frequent prostitutes, if you avidly collect hardcore porn (all of which prominent moralistic conservatives were revealed to have done in recent years) -- then it's probably not a good idea to launch holier-than-thou attacks on heathen Democrats.

If Republicans need to learn to take the fire-and-brimstone out of their politics, Democrats need to turn up the flame. This doesn't mean resorting to dirty campaigning. It means fighting to win. On Saturday, Al Gore emerged from self-imposed exile to stir the party faithful at the Florida Democratic Convention, amping up his rhetoric on Bush ("I'm tired of this right-wing sidewind!") -- and finally embracing the Cliinton-Gore legacy (hey, better late than never). But not all of the assembled partisans were willing to buy this new action-man Gore. Florida Rep. Corrine Brown told the New York Times she was undecided about backing Gore in 2004: "He has to be hungry." Like many other Democrats in her state, Brown is still haunted by Gore's wilting act there during the presidential recount. "[The Republicans] sent in the lions. And he let them take it away from us."

If David Brock's book is a must read for every liberal and moderate who wants to know what the conservative movement is capable of doing to win power, there is another book that is equally important for Democratic voters to read as they contemplate the political future. This is a book that shows not just how Republicans win, but more important, how Democrats lose. It is Jeffrey Toobin's "Too Close to Call: The 36-Day Battle to Decide the 2000 Election." Published last fall while ground zero was still smoldering, the book did not get the attention it deserves. But as Al Gore and Joe Lieberman emerge again into the political spotlight, it is essential reading for any voter who dreads a replay of the 2000 election.

To read about the Gore-Lieberman "battle" in Florida, if you can call it that, is to read of cows lumbering toward slaughter with bovine equanimity. Toobin describes the glaring "passion gap" between Gore's and Bush's post-election campaigns. While the Bush camp, under the masterfully cunning leadership of James Baker, treated the contest as the political battle that it was -- putting protesters in the streets, inciting the always volatile Cuban community, fighting for every ballot (even the patently illegal overseas ones) -- Gore generals Warren Christopher and Bill Daley took a cautious and dithering approach, relying entirely on the legal system, and winding up in the abattoir of the Rehnquist-Scalia Supreme Court.

From election night on, Gore's camp exuded a defeatist air. Ever attuned to the elite media, Gore decided to concede as soon as the networks reversed themselves and called Florida for Bush. It was President Clinton, exiled from the campaign but still the consummate political player, who thought to phone Gore's own vote counter in Florida to double-check the networks' tally. While Baker was telling his troops that victory alone mattered, the anemic Christopher was advising Gore, "You can run again. You don't want to be known as a sore loser. You don't want to fight for too long." Daley, who fretted more about pundits calling him a crooked ballot-stuffer like his old man than about winning, soon fled the Florida battleground altogether for the serenity of Washington. Then there was Joe Lieberman -- a warrior for victory in private strategy meetings, but a wimp whenever he went before the cameras, even conceding in one interview that the Bush team should be allowed to count illegal military ballots. (Toward the end, Lieberman would not even go on TV, whining to the Gore camp that he was "overexposed.") Like Lieberman, Gore's main concern was to appear fair and reasonable to the Washington establishment and the New York Times editorial board. So while Gore ordered Jesse Jackson to pull his protesters from the streets -- he found the demonstrations "incompatible with the solemnity of the recount process," writes Toobin -- the "Brooks Brothers" riot of GOP congressional aides succeeded in shutting down the Miami-Dade County recount. Late in the game, Gore had second thoughts about conceding even the streets around his house to Karl Rove-organized protests. "He finally grew so irritated by the Republican chants outside his home at the Naval Observatory that he asked [campaign manager Donna] Brazile to arrange for some counterdemonstrations to drown them out. 'These people don't want to go to your house,' Brazile told him. 'They want to go to Florida!'"

The tougher Gore combatants in Florida soon grew fed up with the gentility of the Democratic strategy. "You don't understand," said one exasperated operative to his Washington colleagues. "This is Guatemala down here."

How should the Democrats have fought the Florida battle? The way the armchair general back in the White House -- a man who knew something about how to beat the Bush family -- was telling anyone who would listen, which unfortunately did not include the Gore circle.

"Whereas Gore regarded the battle as primarily legal, Clinton saw it as political -- and fierce," writes Toobin. "Gore wanted no demonstrators in the streets; Clinton wanted lots of them. Gore worried about pressing his case in court; Clinton thought the vice president should have sued everybody over everything. Gore believed in muting racial animosities about the election; Clinton thought that Democrats should have been screaming about the treatment of black voters. Gore believed in offering concessions, making gestures of good faith; Clinton thought the Republicans should be given nothing at all but should rather be fought for every single vote. 'He got more votes -- more people wanted to vote for him. This is the essence of democracy. But the fix is in. This thing stinks.'"

These are the instincts and passions of a winning politician. And this is why Clinton always elicited rage from his political enemies, while Gore only drew contempt. "Why did they hate me so much?" Clinton likes to say. "Because I won."

There's a chance, of course, that Al Gore has learned to become a winner during his long, dark night of the soul following Florida and what Toobin calls "the crime against democracy." But he has to prove it, and it won't -- nor should it be -- easy. The Democratic Party should treat him as just one more candidate for its 2004 nomination, putting him through the type of crucible he was largely able to avoid in the 2000 primary contest. During the upcoming primary season, the winning Democratic candidate must show that he or she can not only weather the most withering assaults, but punch back, cleanly and devastatingly. The Democrats will need a Kennedy or Clinton-style battler to face the Bush reelection machine in 2004, because the Bush dynasty has amply demonstrated it will do whatever it takes to win. And the Republican candidate will be surrounded by a movement of true believers that, as David Brock has revealed in gory detail, will do even more than that.

Shares