As the situation in Israel and the occupied territories descends into ever deeper circles of hell, some Israelis can cling to the threadbare satisfaction of knowing that they predicted it. For many liberals here, the collapse of the Oslo peace process, the smashing of the Palestinian Authority, the rise of terrorist attacks and the total militarization of the conflict were all preordained when Ariel Sharon was elected prime minister 15 months ago.

For months, increasing violence has threatened to explode in Israel and the territories. In late March, it finally did. For the last three weeks Israel has been engaged in the largest military operation in the West Bank since the 1967 Six-Day War. After the "Seder massacre," a suicide bombing in the seaside city of Netanya that killed 29 Israelis, Sharon launched a furious offensive against the Palestinians. Tanks and armored cars smashed into a half-dozen West Bank cities, with helicopter gunships hovering overhead, pounding into submission densely inhabited Palestinian neighborhoods, including the historic casbah in the biblical city of Nablus. Thousands of Israeli reservists have been called up to man the guns, and the word "war" is used more and more often as a matter of course to describe the campaign's staggering death toll and reach.

The heart of the devastation is at the Jenin refugee camp, where the number of dead buried beneath tons of rubble is unknown and a bitter and momentous controversy about what happened there is raging. Palestinians charge that a massacre took place, with hundreds killed; the Israelis deny their army did anything wrong and put the number of Palestinian dead in the dozens. Human rights groups and British and European officials, fearing that atrocities took place in Jenin (from which journalists were banned until a few days ago), have called for an international investigation. Chris Patten, external relations commissioner for the European Union, warned that if Israel did not accept a U.N. investigation, its reputation would suffer "colossal damage."

Blasted Jenin is quiet now, but the Israeli army and Palestinian gunmen are still engaged in two tense standoffs, one in Bethlehem around the Church of the Nativity, the other in Ramallah at Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat's West Bank headquarters, where Israelis charge that those responsible for the assassination of an Israeli cabinet minister are holed up. And Israeli soldiers are still arresting and processing hundreds of fighting-age Palestinian men -- including on Monday afternoon Marwan Barghouti, the West Bank head of the Fatah political party affiliated with Arafat, a big fish Israel says is responsible for ordering terrorist attacks on Israelis. The fighting in the occupied territories has largely subsided, though shooting flared up again Wednesday at the Church of the Nativity.

The intensifying crisis led the Bush administration to belatedly get involved, sending Secretary of State Colin Powell to the region. But as many predicted, Powell departed the region Wednesday with almost nothing to show for his trip. Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon continues to bluntly rebuff vacillating U.S. calls for an end to the invasion, while Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat, who has been confined to his devastated headquarters in Ramallah for weeks, refused to call for a cease-fire until Israeli forces withdraw from the occupied territories. A final meeting between Powell and Arafat on Wednesday produced no breakthrough; indeed, after Powell left, angry Palestinians asserted that his intervention had achieved nothing. Chief Palestinian negotiator Saab Erekat said, "The situation on the ground is that Secretary Powell leaves the situation much worse than he came."

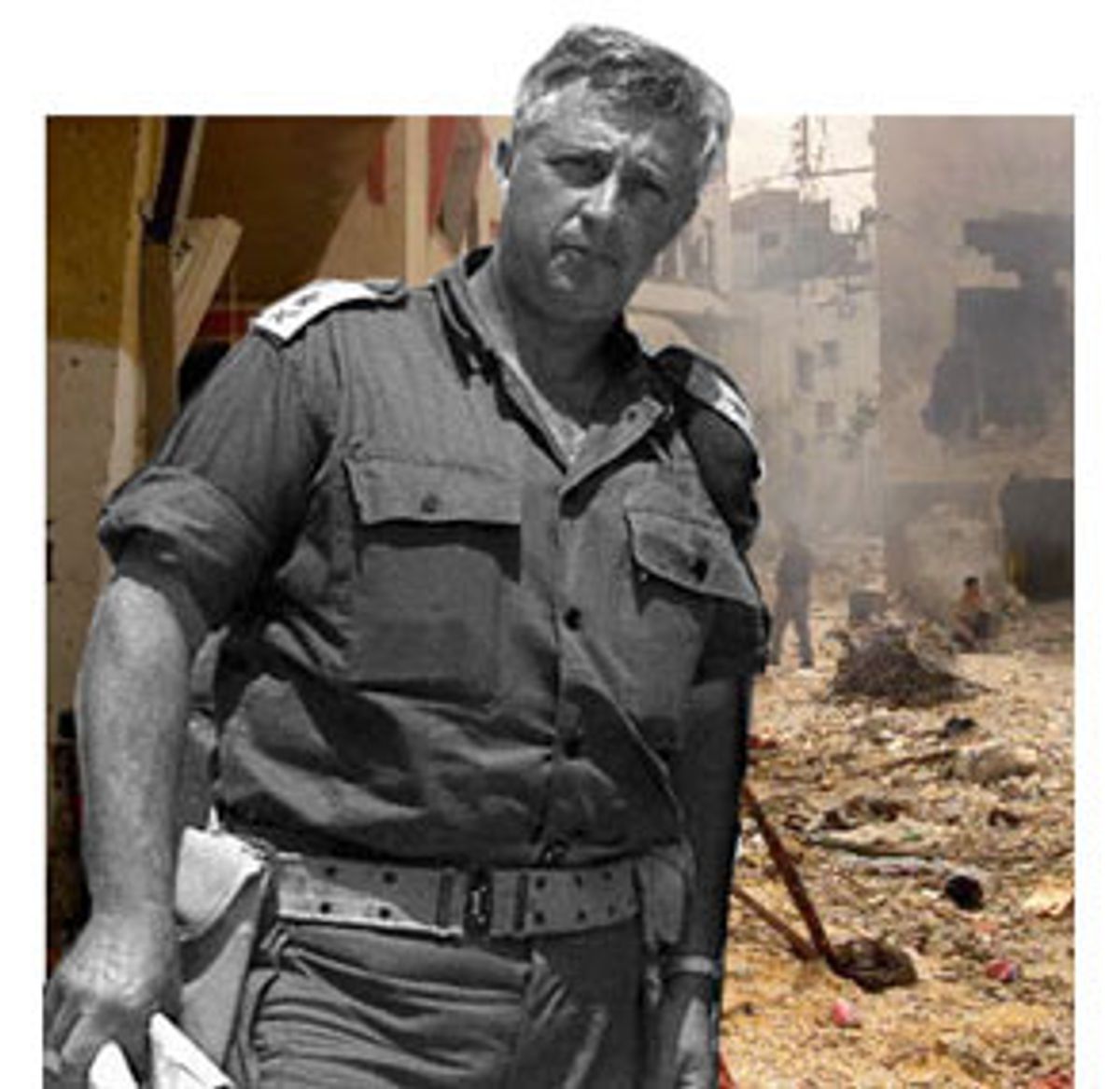

As the world waits for the next development -- which painful experience indicates will probably be a dreadful one -- a question arises. How did the Israeli-Palestinian situation deteriorate so far so fast? How did the so-called Al-Aqsa Intifada, which began after Ariel Sharon, accompanied by hundreds of policemen, made a controversial visit to set foot on the esplanade of the most contested holy real estate in the world in September 2000, move from riotous stone-throwing to full-fledged war?

The violence had an escalatory dynamic from the start: Israeli police brutality and the rage following the first Palestinian funerals produced increasingly violent riots. Palestinian gunmen and Israeli soldiers traded bullets. Israel's policy of knocking off wanted Palestinian militants (and innocent bystanders) angered Palestinians who vowed revenge. And Palestinian terrorist attacks on Israeli civilians whetted Israel's appetite for drastic military action. These are the "cycles of violence" that diplomats have urged, over and over again, both parties to break.

But for left-wing Israelis who campaigned against Sharon's election as prime minister in February 2001, the terrible events of the last year have come as no surprise. In fact, they predicted them with uncanny accuracy -- and lay responsibility for them directly at the feet of Ariel Sharon.

The left-leaning Ha'aretz, Israel's most prestigious newspaper, reminded its readers last week of the advertisement run by Labor on television 15 months ago. The clip, which predicted in graphic detail what would happen if Sharon were elected, forecast the reinvasion of Palestinian territories, hundreds of deaths, the deterioration of Israel's relations with Jordan and Egypt and a massive call-up of reservists. In a publicity gimmick that was much criticized at the time, mock call-up cards were also sent to reservists to stress the danger inherent in choosing Sharon, a man known for his ruthlessness and checkered military past, as leader of the Jewish nation. The admen "should be congratulated on their prescience," wrote Aviv Lavie in Ha'aretz.

"From day one, Sharon's main decision was to ruin the Oslo peace process and destroy the Palestinian Authority," says Ron Pundak, one of the early architects of the Oslo accords, now director of the Peres Center for Peace in Tel Aviv. "It was just a question of timing and a matter of how tactfully and skillfully to create an environment most conducive to reducing U.S. pressure and domestic opposition to his plan. It took him a year until he reached this moment and unfortunately Arafat played into his hands."

Ha'aretz commentator Doron Rosenblum predicted the current crisis two and a half months ago. In a savage column titled "The State Rejoices, the Nation Bleeds," Rosenblum wrote, "[T]he inevitable and the obvious happened quite quickly: The mask of the restrained grandfather dropped. Sharon is Sharon is Sharon -- escalation, provocation, complication and all. Even as prime minister, he has turned out to be a 'one-trick pony,' obsessively repeating the exercise of encircling, tightening and siege remembered from the days of the Second Army in Sinai, through Beirut and on to Ramallah ... The suspicion arises that even the Lebanon War will turn into an aperitif to the dish Sharon is now boiling up in the territories in a huge pressure-cooker. By closing off all the openings for negotiations, sealing the lid on his personal foe and raising the temperature of the motives of hatred and revenge, it seems that he is consciously cooking up some big explosion."

During the election campaign Sharon himself was candid about his tough intentions. He promised "peace through security," not the other way around. And ever since the Oslo accords were signed in 1993, Sharon had harshly criticized, in opinion pieces and Knesset speeches, the land-for-peace negotiation process. This was not surprising, since Sharon's entire career has been defined by battling the Palestinians and other Arabs militarily, on the one hand, and masterminding the building of settlements in the West Bank and Gaza to create "facts on the ground" that would make it impossible for Israel ever to give back the territories it occupied after the 1967 war, on the other.

Like other Israeli politicians, he toned down the virulence of his criticism after Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, the accords' signatory, was assassinated by a rabidly pro-settlement and religious Israeli who believed that Rabin had betrayed the Jewish people. But in a well-publicized interview with Kfar Chabad, a religious weekly, last January, Sharon declared: "The Oslo agreement no longer exists. Full stop." He said he would never give up a single Jewish settlement in the West Bank and Gaza nor divide Jerusalem. When pressed by other journalists to define his vision of a Palestinian state, he described an entity with no control over its borders, cut up by security roads, ruling over at most 45 percent of the occupied territories -- in short, the status quo, preserved indefinitely through "long-term interim agreements" and elusive promises.

The Palestinian response to Sharon's hard-line positions was equally clear at the time of his election. "What [Sharon] has proposed means that it is impossible to reach an agreement," Saeb Erakat told the New York Times. "The result is a description of war."

So when Sharon was elected in a landslide last February, did Israelis expect war? "Many did," says Yaron Ezrahi, a political analyst at the Israel Democracy Institute, a Jerusalem think tank. "There was a mood after the collapse of [talks at] Camp David, that if the diplomatic general [Ehud] Barak [then Israel's prime minister] had come home empty-handed and Arafat had sent us his armed people, we needed to send them the neighborhood gangster [Sharon] and use force against force."

There were other signs that the conflict would escalate under Sharon. Operation "Defensive Shield," as the current campaign is known, was triggered by the deadly suicide bombing in Netanya on the first night of Passover. But the option of reinvading the West Bank and/or Gaza had been discussed as a contingency plan by politicians, pundits and generals months before. Similar operations, on a smaller scale, had been launched repeatedly over the past year: Tanks moved into Palestinian cities after the murder of the Israeli Tourism Minister Rechavam Zeevi last October, for example, and soldiers practiced urban warfare against the Balata refugee camp at the beginning of March. Those were clearly dress rehearsals for the big operation Sharon had been planning all along, says Pundak.

That Sharon's true intention was not simply to put an end to the suicide bombings that have been crippling Israeli life but to smash everything that might make up a Palestinian state is shown by the type of people and buildings the army has targeted in the current campaign, says Pundak. "At the same time as the army is fighting the so-called terrorist infrastructure, it is ruining the Palestinian Authority, breaking in offices, destroying records and dismantling police forces." The population registry, for example, no longer exists. While Israel pounds what remains of a crippled, ineffectual Palestinian administration, Sharon has allowed "the leadership of Hamas and Islamic Jihad [who oppose all peace agreements with Israel] to go on living happily in Gaza," says Pundak. Ironically Sheikh Yassin, the spiritual leader of Hamas, the organization behind the most lethal terrorist attacks, hasn't been disturbed, he says -- "not even his afternoon nap."

Other Israeli analysts, however, caution against charging Sharon with "premeditated war." Nahum Barnea, a political columnist for Israel's highest-circulation newspaper, Yedioth Ahronoth, says Sharon has "master instincts," not a "master plan." "Saying it looks like a plan is a way of relieving the burden of responsibility on Arafat, but it's not right," says Barnea. "From day one foreign journalists have portrayed Sharon as a very strong person. He is not. When he became prime minister, he was torn between contradictory agendas, caught in the political and military situation. It's not easy being prime minister of Israel and go to sleep only to be woken up four times at night by news of bombs or soldiers being killed."

Other analysts argue that Sharon did not necessarily set out to roll back the concessions made since Oslo. "There's no question in my mind that when Sharon went to the Temple Mount he intended to derail Oslo," says Hirsch Goodman, senior research associate at Tel Aviv University's Jaffee Center for Strategic Studies. "Sharon saw a prime minister of Israel [Barak] ready to give back 97 percent [the actual percentage of land offered by Barak is in dispute] of the West Bank and Gaza and to divide Jerusalem and he thought he had to stop it." But Goodman adds: "His intention was to stop Oslo where it was but not to destroy it. He was ready to have a Palestinian state declared without borders and to negotiate long-term interim agreements."

Pundak disputes that, painting the picture of a man who would never accept a peaceful compromise on the basis of Oslo. "[Sharon] thinks Palestinians don't deserve more than limited self-rule. He doesn't trust Palestinians and thinks we're engaged in a conflict that will last another hundred years. His thinking, shaped by his experience as a general and the climate of the 1960s, is that a Palestinian state would be a bridge to other outside Arab forces [like Iraq] who would use it to destroy Israel. He thinks it's a lousy arrangement to help them with a peace process."

In any event, "Oslo as a process was already dead after Camp David," notes Barnea. After putting major issues like the status of Jerusalem holy places, the fate of refugees and the shape of final borders on the negotiating table, there was no going back to the incremental land-for-peace process begun at Oslo. And then there was the second intifada, in which Arafat has embraced violence. "Sharon didn't have to send soldiers in Jenin to shoot it," says Barnea of the Oslo diplomatic process. "He only had to bury it."

That doesn't mean the yearlong slide toward war was entirely involuntary. "Nothing is involuntary," says Barnea. "Arafat and Sharon have both accomplished their basic agendas."

According to him, "Arafat wanted to have a grand finale and not to finalize the diplomatic process. He wanted a final act involving lots of violence and he got it. It was a question of historical legacy but also because he believes he has no chance to get what he wants with a signed agreement. He sees a signed agreement as only one way of achieving his goal. When he committed himself not to use violence at Oslo, he did not mean it. That is what has offended Israel most -- the notion that he resorted so easily to violence after the failure of Camp David."

"In Sharon's case, his agenda goes back much earlier than Oslo. Every Israeli leader has a certain amount of suspicion for signed agreements with Arabs, but Sharon takes that suspicion to the extreme," says Barnea, who's been observing Israeli politics up close for years. "He has a problem with having an agreement with Arafat."

"I remember a trip in Washington in the spring of 2001," says Barnea. "It was late at night and I asked him, to distract him, what he thought about bin Laden. This was before Sept. 11. He looked at me with surprise, as if wondering why I wasn't asking him about Bush and Arafat, and said, 'Arafat is bin Laden.' I got a quote but I think it also reflects his way of thinking. His idea of Arafat was crystallized in 1982 in Beirut and he's never changed it." (In 1982 Sharon, using the attempted assassination of an Israeli diplomat by a dissident Palestinian faction as a pretext, launched a full-scale invasion of Lebanon with the intention of smashing the PLO and setting up Lebanon as an Israeli client. Arafat and his troops, trapped in Beirut, were forced to flee Lebanon for Tunis. Sharon recently said he regretted not giving an Israeli sniper an order to kill Arafat as he boarded the ship.) To this date, Sharon has always refused to shake the Palestinian leader's hand -- even at the Wye River Plantation where he joined then-Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu and Arafat for intensive talks in a secluded setting.

Then there is the question of settlements. The Jewish implantations in the West Bank and Gaza are Sharon's brainchild and legacy, a project he has overseen in every ministerial role he has held over the decades. "When he was elected people said that now that Sharon is old, he will put the safety of his children and grandchildren before the settlement enterprise, but they're wrong," says Barnea. "His real grandchildren are the settlements, the ones built in the middle of Palestinian population. It would be very difficult for him to evacuate them. For him Israel has to be in Paradise, living in a state of utopia, in order to give up one settlement."

Critics have accused Sharon of deliberately scuttling chances for a cease-fire in the past year by approving provocative military actions -- in particular the so-called targeted assassinations -- at times when Palestinian guns were quiet. Sharon's ultimate goal, they charge, is to buy time and avoid reaching the phase of painful political concessions that would require freezing construction of new housing in the territories and, eventually, dismantling his life's work by giving Palestinians control over most of the West Bank and Gaza.

Political analyst Ezrahi argues that Sharon planted the seeds of the current war simply by promoting settlement-building on conquered land. "It was terribly short-sighted and unsophisticated. Anyone who knew anything about national liberation movements knew that [settling territories conquered in 1967] would be untenable and could only end in bloodshed. Sharon was driven by narrow conceptions of history and Darwinian perceptions of the relationship between Israelis and Palestinians."

But if the settlement enterprise was "the worst act taken by Jews against themselves since 1948," Ezrahi stresses that Palestinians have also made a fatal historical mistake by resorting to terror: "Terrorism has profoundly infected the Palestinian movement," he says. "It wakes up terrible memories of the Holocaust. It was the worst possible way of forcing us [Israelis] to compromise."

The general consensus among analysts, however, is that Sharon is following his instincts and doesn't have a long-term plan for what Israel and its relationship with the Palestinians should be. "I don't know what his vision is. He's a brilliant tactician but not a very good strategist," says Goodman -- who makes clear that he also believes Arafat planned all along to use Oslo as a Trojan horse that would lead to the destruction of Israel. Moreover, Sharon is not an ideologue about the settlements, he says -- distinguishing him from the ultranationalist and religious parties and individuals that believe that "Judea and Samaria" were given by God to Israel. "He's primarily concerned with security-oriented issues and he thinks settlements are key to Israel's security."

"It would be an error to take the positions he voiced as a member of the opposition and to project them to understand Sharon's present behavior," says Ezrahi. "These positions were meant to galvanize his constituency. Of course, what he does now is not entirely apolitical. He does it with the intention to crush Netanyahu who has been calling for more action [against Palestinian militants]. Netanyahu is the silent partner, the Iago in this play, inciting Sharon's Othello to go further."

Explaining Sharon's "master instincts" and his failure to have a coherent endgame strategy, Barnea says, "Sharon has principles that are the product of his childhood, of his time in the army and the issues he faces on the political scene. At the same time he has to think about the survival of Israel, his coalition ... All master plans melt in the Israeli sun. Israeli politics are so intensive and constantly changing, that it's very difficult to implement a plan."

"If there are no results to the military offensive, the [Israeli] public can easily turn left and not right," says Barnea. "The Israeli center is zigzagging. You see it in the polls. There is overwhelming support for both military action and wide political concessions. There is no contradiction here. Israelis hate to be impotent and solutionless."

The question, then, is whether after a year and a half of escalating violence there will be a reasonable Palestinian partner to talk to. "Without a different Palestinian voice and a different Palestinian vocabulary [from the current rhetoric of hatred and intransigence], it will be very difficult to convince Israelis who see that Sharon's way has failed to vote for an alternative," says Pundak, who spent many hours with members of the Palestinian Liberation Organization (then an illegal terrorist entity) secretly plotting the Oslo breakthrough. "The track record of Palestinians is bad. They have a history of doing the wrong thing at the wrong moment," he says. "But there are still pragmatists among them and we can still make a deal."

Pundak mentions Marwan Barghouti as an example of a Palestinian pragmatist who would embrace a deal along clear political guidelines. An hour later, Israeli television killed that hope, reporting that the Israeli army had just seized Barghouti, once an outspokenly pro-peace politician who had many meetings with Israeli doves. Israeli officials charged that Barghouti was responsible for turning the Tanzim civil guard, part of Arafat's mainstream Fatah movement, into a militia that carried out suicide bombings against Israelis. Israeli security officials and politicians were divided about the wisdom of arresting the highly popular West Bank leader. Politicians on the right called for a public trial and Barghouti's execution, those on the left called for his release. Centrists defended his arrest, but warned that it would lead to bloody reprisals or kidnappings.

Ezrahi joins an increasing number of observers who believe that Sharon and Arafat, two old warriors who cannot change their ways, stand in the way of peace. "It's a tragic conflict fed by unforgivable misconceptions on both sides. Sharon and Arafat are like Siamese twins. There can be no victory of one against the other because of our territorial and demographic proximity. But the real big losers in this war are the Israeli and Palestinian people."

Shares