As the New York Times reported it, a recent Supreme Court argument on whether public schools may impose drug tests on their students was “intense and sometimes downright nasty.” Before the court was a school district’s regulation requiring drug tests of students involved in any extracurricular activity. Although there was no reason to suspect that the plaintiff, Lindsay Earls, had ever used drugs, she was called out of choir and tested — specifically, ordered to urinate under a teacher’s supervision. Earls passed, but brought suit against what she believes was an invasion of privacy and an unconstitutional search. It’s an important case: Many school districts are expected to institute routine, random drug testing if the court finds it constitutional, and expulsions of students who fail are sure to follow. It could also inflict severe damage on the Fourth Amendment, which for two centuries has protected individuals from searches and seizures unless there is at least some ground to suspect wrongdoing.

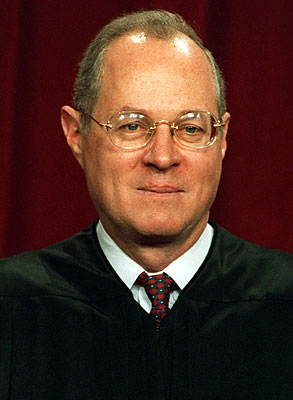

“Most surprising,” said the Times, “was Justice Kennedy’s implied slur on the plaintiffs.” The justice imagined a school district with a “drug testing school” and a “druggie school,” and told the lawyer representing the Earls family that no parent would send a child to the druggie school “except maybe your client.” This was remarkable in two ways. First, it was indeed a slur: Lindsay Earls had passed the drug test, and her cause was not drugs but the Fourth Amendment. Second, the very irrationality of Kennedy’s remarks, coupled with his demeanor — the Boston Globe described him as red with emotion as he launched his “bitter verbal attack” — betrayed an uncontainable anger toward a litigant that is entirely absent from Supreme Court arguments on even the most heinous murder cases.

Irrational anger is one kind of prejudice, and a federal law exists to insulate judicial rulings from it. This law requires a judge to “disqualify himself in any proceeding in which his impartiality might reasonably be questioned.” As Kennedy himself said in another case, “any judge who understands the judicial office and oath” would insist on his own recusal when his attitude even appears to be less than detached and impartial.

In some ways, though, Kennedy’s breach was not remarkable at all, but emblematic of the harsh and contemptuous treatment dished out to those on the wrong side of the drug war. We shouldn’t be surprised that the drug war can vanquish the impartiality of a respected jurist when it routinely undermines so much else that we value. Most obviously, it trumps liberty; the drug war has given us the most incarcerated population in the industrialized world, with one-quarter of our 2 million inmates imprisoned for nonviolent drug offenses, and over 1.2 million arrests annually for drug possession alone.

It also trumps much of our national agenda. There’s the drug exception to public health: Federal law denies health benefits and food stamps to ex-drug offenders. Equal justice? African-Americans comprise 13 percent of all monthly drug users but 74 percent of those imprisoned for drug possession. Homelessness? Last month the Supreme Court unanimously ruled that families can be evicted from public housing on the basis of their child’s use of drugs, even if it takes place out of the house and the family knows nothing about it. Compassion? Consider the Justice Department’s aggressive effort to ensure that cancer patients don’t get the medical marijuana that could alleviate their pain. In short, the dehumanizing prejudice once conveyed by the epithet “junkie” remains entrenched 50 years later, promoting a thoughtless disregard for the lives and welfare of those Justice Kennedy now calls “druggies.”

In recent years students have become targets of the drug war too. Many thousands of students have been forced to forgo college by a federal law that denies them college loans because they were once convicted of a drug offense, and thousands more have been removed from secondary education under the zero-tolerance drug possession punishments that exist in 90 percent of public schools. The court now seems poised to decide that even without any grounds for suspicion, all students are suspect. By most accounts, Kennedy will be casting the deciding vote — a vote that will transmute Kennedy’s unfounded assumptions about Lindsay Earls and “druggie schools” into an unfounded constitutional presumption about all schoolchildren.

Justice Felix Frankfurter once wrote that when a judge cannot “think dispassionately and submerge private feeling” he should recuse himself. The occasion was a case concerning the constitutionality of employing Muzak on D.C. buses, an innovation the justice detested. He looked into himself and found his “feelings so strongly engaged” that he should not participate in the judgment. In recusing himself, Justice Frankfurter honored the court and its commitment to “the rule of law, not men.” Justice Kennedy would do well to follow his example.