Joseph Byrd recorded a pair of experimental psychedelic albums for Columbia Records in the late 1960s. Since then, he says he's earned a few thousand dollars in composer's fees but hasn't received a single penny in artist's royalties.

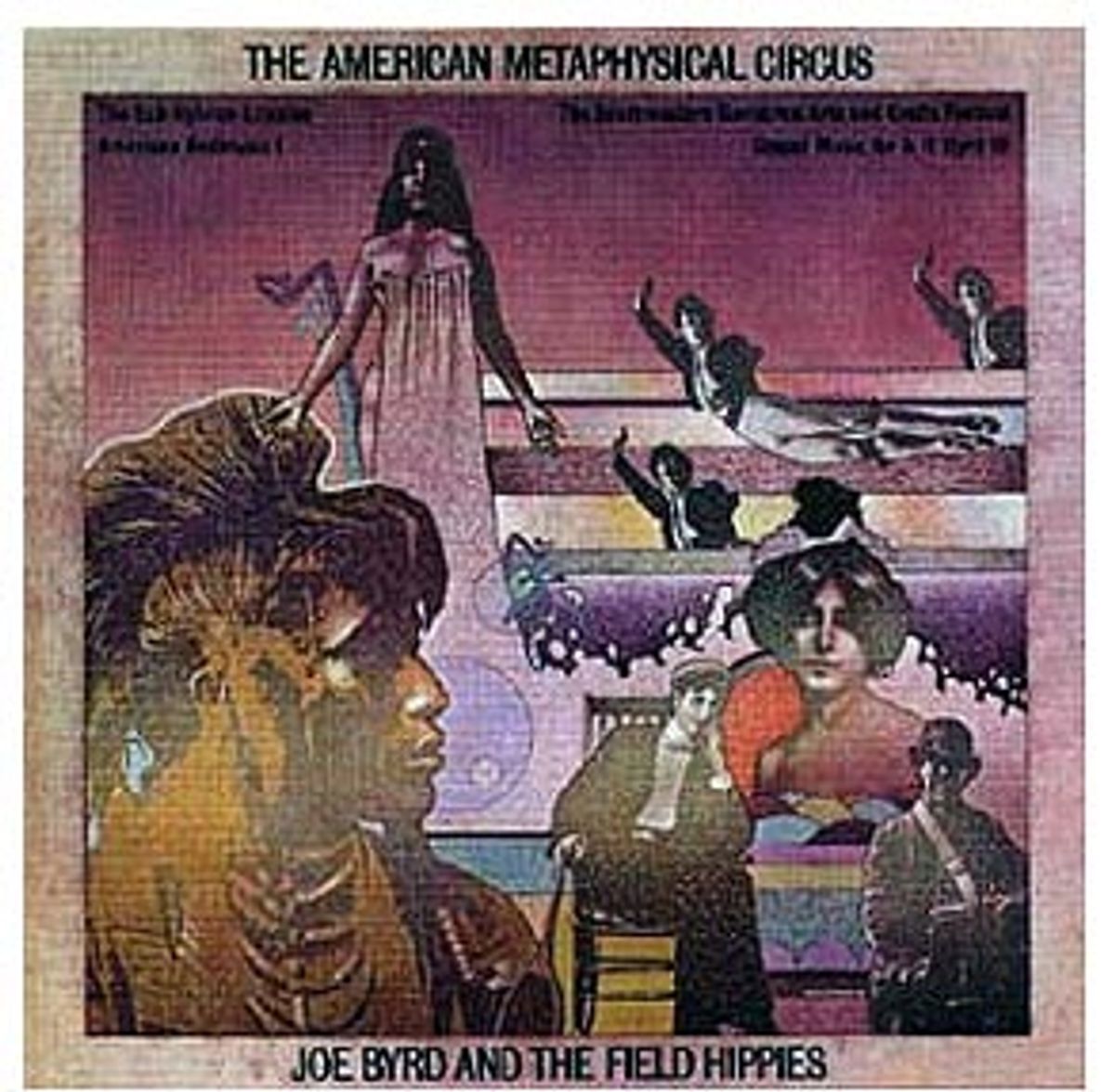

It's not for lack of trying. Byrd says he sent his first letter of complaint to the label in 1976, and over the years he's repeatedly asked for financial statements on album sales and royalties. Letters have been sent, phone calls have been made. But even as his recordings -- "The United States of America" and "The American Metaphysical Circus" -- began to reappear on compact disc, Columbia and its parent company (Sony) continued to ignore Byrd's pleas.

On Feb. 27, the mild-mannered professor -- Byrd teaches music history at the College of the Redwoods in Northern California -- decided to take his case to Marilyn Hall Patel, the federal judge overseeing the labels' lawsuit against Napster for copyright infringement. He wrote Patel a letter detailing how Sony had been giving him the cold shoulder for decades. His situation, he added, was hardly unique.

"I am not alone," he wrote. "Literally thousands of musicians like me, who are purportedly represented by record companies and distributors in the current Napster case, are in my situation."

"The record companies' representation that they are legitimate agents for their artists is false," he continued. "The only payments they make are to those who have the means to force them to be accountable; to the rest, a vast majority, they pay nothing. Therefore, allowing them to collect fees in our behalf does not serve the public interest. I personally would prefer to allow my music to be freely shared, to the present situation, in which only the corporations stand to gain. Until this is changed, the record companies and publishers deserve nothing."

Byrd is hardly the first artist to express his distaste for how record companies do business. But Byrd's letter comes at a time when the music industry is in a crisis. Record sales are down for a variety of reasons, and consumers are in open revolt. While KaZaa and other free file-sharing services continue to grow, the Department of Justice is investigating whether the industry colluded to undermine pay-for-play competitors to its own online services. Meanwhile, artists of all stripes, from Byrd to Sheryl Crow, are challenging the status quo.

Some, through nonprofits such as the Future of Music Coalition and Don Henley's Recording Artists' Coalition, are uniting and testifying before Congress. Others, like 1950s pop star Peggy Lee, who led a class-action settlement that restored unpaid royalties just before her death on Jan. 22, have gone to court and won. Even bruised and battered Napster, shut down since last July, has helped shift the balance of power away from the industry by persuading Judge Patel to issue an order that forces the major labels to prove that they own the songs that were once available on the file-trading service.

All of these developments "give you a keyhole view into the way the industry works or doesn't work," says Steve Cohen, one of Napster's lawyers. The music industry's crisis, he argues, is bound to have an effect on the way that artists are treated. "It's like someone has taken one of those snow scenes in a bubble and shaken it up."

Byrd, having been ignored for decades, doubts that the entertainment industry will alter the way it does business. File-sharing and legal scrutiny can only go so far because, he says, "very few people can afford to turn down the exposure you get from a major label or film distributor." As long as the big labels and media companies are big enough to launch careers, he says, they'll have the ability to relegate artists to near-servitude status.

Byrd's failure to earn artist's royalties stems in part from his inability to find a copy of his contract. "I've looked everywhere," he says. "One of the only things that I am sure of in this case is that it's nowhere to be found."

Sony also couldn't unearth Byrd's contract in time for this story, but if it was like others from that era, suggests one entertainment lawyer, Byrd may not be owed as much as he thinks, if he's owed anything at all. Contracts from the decade of free love made it particularly difficult for artists to make money, says Walter McDonough, a lawyer who works with the Future of Music Coalition.

"For a lot of people who recorded in the '60s, the royalty rates were a lot lower," he says. "A lot of the contracts paid royalties that are two-thirds of what they are now."

Specifically, after production, marketing and touring are paid for, today's contracts pay out about 15 percent of record sales; artists get about $2 for every $14 or $15 CD that's sold. Contracts from the 1960s era typically paid about 6 or 7 percent, or $.50, for records that cost about $7 at the time. And it's not even clear that Byrd's albums ever recouped their initial production cost, which, according to Byrd, was about $45,000.

Byrd says that "The United States of America," his first album, largely flopped on release. But the album was re-released on compact disc in the 1980s and is still available. In a 1999 letter to Sony, Byrd noted that, in light of the re-release, it "certainly has royalty payments due."

"The American Metaphysical Circus" has been more successful, says Byrd, although he doesn't consider it his best work; he's actually a bit embarrassed about the album's odd, trippy feel. But there appears to have been enough of an interest to keep the album on record-store shelves. "I went to a record bin a while ago, and 17 years after it was recorded, there it was," Byrd says. "I asked a clerk and he said it was still in the catalog."

Byrd believes that the album wouldn't still be available if it weren't selling. So even if only a few thousand albums or tapes or CDs are sold each year, Byrd figures he's owed several thousand dollars. His experience with other albums confirms his sense that there is money due. In 1978 he produced an album for Ry Cooder called "Jazz." "That cost $75,000 to make and it took about two years to pay off the debt," he says. "Then I started getting royalties."

It's not as if Sony has no idea who Byrd is, either. Five years ago Sony's publishing wing called to ask Byrd for his signature because the British band Portishead wanted to cover one of his songs.

Composer rights, which are due publisher royalties, are different from artist's royalties; labels oversee the latter while publishing royalties are distributed by the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP). But up to that point, Byrd had received neither.

"I said I would not cooperate until I had received a statement of royalties due me," Byrd says. "In response I received no statement, but a letter of agreement that in exchange for $6,000 I would waive all rights to past composer royalties. I signed in a New York minute. Since then, the publishers have sent a yearly statement and royalty check (the most recent was $1,800)."

But still no artist's royalties. Byrd's problem may have been caused by simple oversight, says McDonough. Sony's purchase of CBS Records and Columbia in 1987 is only one example of an ongoing massive industrywide consolidation, "and with consolidation, there are fewer people doing more work," McDonough says. "They don't have time to dedicate to these kinds of things." He suggests that Byrd hire a lawyer and an auditor who would check Sony's books and get a copy of his contract.

But Byrd says he doesn't have the money to pursue Sony in court. Teaching music history, cashing the occasional royalty check -- his income doesn't do much more than pay the bills. "The contract I signed was subject to New York state jurisdiction," he says. "I could not even walk in the door of a Manhattan entertainment law firm without a check for $10,000, and I have no proof that the royalties would be enough to pay for that."

He knows that the Dixie Chicks sued Sony last summer (alleging that the label owed them $4 million in unpaid royalties) but, Byrd argues, he and most other so-called middle-class artists don't have the resources or incentive to mount a legal challenge.

"Unless you have the Dixie Chicks kind of potential for vast sums owed, who can afford to sue?" he says. "To say nothing of the cost of an audit, if matters got that far."

The lack of alternatives -- given the futility of his position and Sony's refusal to answer the nine or 10 letters he's sent since 1976 -- has yet to make Byrd particularly angry. He says he is bothered by what he calls the industries' "cynical confidence," the way the Recording Industry Association of America can claim with a straight face that it is fighting the file-trading scourge on behalf of artists. But his overall reaction has largely been one of amazement at "the fact that nobody has ever managed to make these people do business like businesspeople," he says. "If they can screw Peggy Lee or the Dixie Chicks, then they can pretty much get away with anything."

The RIAA and groups like the Future of Music Coalition beg to differ. Both organizations, though usually lined up on opposite sides, contend that artists are stronger and better off now than ever before.

"The industry has changed dramatically since those days [when Byrd was recording]," says John Simson, executive director of SoundExchange, a record industry group that collects webcasting royalties. "Artists have better resources than they ever did in terms of lawyers or other people who understand the business. And there's been a significant change in contracts: They've gotten shorter; the royalty rates have gotten higher, and so have the advances."

Artists have also won more legal protection. Webcasting royalties became mandated by law in 1995 thanks in part to artist support. And in 2000, artists successfully rebelled after the recording industry persuaded legislators to amend the 1976 Copyright Act to allow them to treat recorded music as "work for hire" -- which would have allowed labels to keep some copyrights for up to 95 years instead of giving them back to artists after 35 years.

The Recording Artists' Coalition and the Future of Music Coalition are now confidently pushing for other legislative changes. The RAC is lobbying the California legislature to repeal the Seven Year Statute, which among other things allows labels to sue artists for undelivered albums. The FOMC sent a letter to federal legislators in late March that proposed giving the rights to out-of-print titles back to the original artists.

"Our suggestion to the House and Senate judiciary committees is that there should be a compulsory license where the rights go back to the artist when the record has been out of print for two years," McDonough says. "If the label isn't using it, if it's been out of print, then an artist should be able to have the rights."

Many industry observers believe that the combination of file-sharing and legal changes will be enough to change the industry's business practices. "[The online copyright battle] raises all these issues that artists wouldn't otherwise be thinking about," says Napster's Cohen. "Their filing system is a lot like the way I file things in my house: I put it all in a box and file it in the basement. It's hard to blame them; they own millions of titles. But when people start asking questions about ownership, when people have a reason to say, 'Show me; I want to know who owns it,' suddenly people in the industry have to be able to answer those questions. So the way they behave in the future will be different. They're going to make sure they don't make these mistakes again."

Still, the victories that artists have won come against an industry that is also fighting vigorously for its tried-and-traditional profits. Napster, after attracting 60 million users, is now essentially dead. The file-sharing services that have risen in its wake are also under significant legal pressure.

In the face of growing uncertainty about the future of their business model, labels have grown increasingly conservative and combative, says Simson. After years of working with artists to give them greater control and higher returns on their own work, he says, the recording industry is now trying to retrench and is largely succeeding.

"What's happened is that with the new digital changes, everyone is very concerned about the business model, so it's made everyone very worried about how to make money," he says. "No one has a crystal ball; people are trying their best to figure things out. But progress has been slowed down because of the uncertainty."

Listeners are already suffering, says Dr. Demento, a friend of Byrd's and the host of a well-known comedy and music radio show. "The majors' broad-brush actions have the probably unintended effect of making the music of Joseph Byrd and other relatively obscure creators of out-of-print major-label releases harder to find than it might be otherwise," Demento says. "And that's unfortunate."

The situation could get worse, says Byrd. "The industry has a history of success, with Congress bailing it out when the courts won't," he says. Take the Betamax case, "which they [the entertainment industry] lost, then won with the mind-boggling legislation mandating payment of royalties for sales of blank VCR tapes!"

"I don't think it's cynical to say that the entertainment business is so corrupt that nothing could change how it does business, short of an entire new Bill of Rights for artists," he says. "And for that to happen, there would have to be a public angry enough to demand that Congress stand up to Hollywood. When was the last time that happened?"

Shares