"Without race, we wouldn't have music, movies, prisons, politics, history, libraries, colleges, private conversations, motives. Dorothy Dandridge. Bill Clinton," writes essayist and journalist Richard Rodriguez in "Brown: The Last Discovery of America." And yet Rodriguez wants nothing more than to undermine race and usher in the idea of a "brown" -- impure, indistinct and contradictory -- America. For Rodriguez, the Catholic gay son of Mexican immigrants, "Only further confusion can save us."

"Confusion" might not be what readers are looking for when trying to make sense out of race and ethnicity. But "Brown," for the most part, is an optimistic, often romantic collection of essays that reflects what's already happening in America: A significant number of Americans define themselves as Hispanic, which, Rodriguez points out, is not a race. Americans continue to melt into each other, despite the census classifications and affirmative action programs that intend to deepen color lines.

"Brown" begins with the essay "The Triad of Alexis de Tocqueville." Rodriguez peels apart the scene from de Tocqueville's "Democracy in America" in which an Indian and an African slave care for a white child, Europe's daughter. The memory of this triad hovers over "Brown," each figure shifting periodically to face one of the other two head-on. How will blacks and Hispanics relate to one another, especially now that the government declares that Hispanics are overtaking African-Americans as the country's largest minority? Will this browning of America help African-Americans? "What I want for African Americans is white freedom," Rodriguez writes. "The same as I wanted for myself."

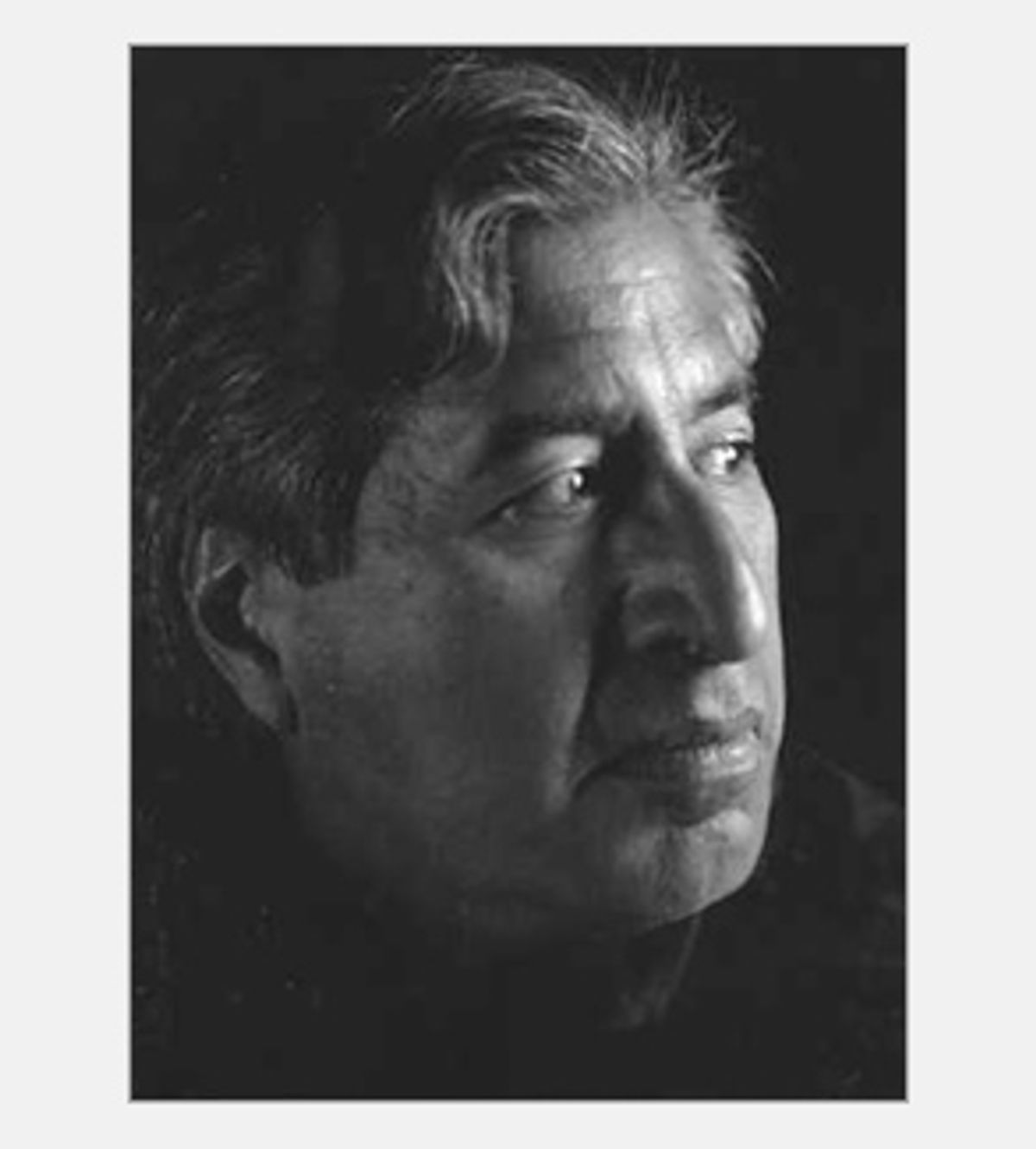

Rodriguez, whose acclaimed memoirs "Hunger for Memory" and "Days of Obligation" are the first two installments in his "trilogy on American public life," spoke to Salon from his home in San Francisco.

Most people might take a look at this book and think you're talking about pigment.

Yes. And Latinos.

But you're talking about "brown" ideas. Can you explain that?

What interests me about the color brown is that it is a color produced by so many colors. It is a fine mess of a color. Initially, I had a sense that most Americans probably regard Hispanics as brown. But my interest was not in the Hispanic part of that observation but in the brown part of it -- what is brown? And it seemed to me that the larger questions about America that the color raised is the fact that we are, all of us, in our various colors, our various hues, melting into each other and creating a brown nation. I tried to write a brown book, that is, brownly, by engaging contradiction and paradox, and rhetorical devices that suggest the way that I experience my own life. That is, for example, as the descendent of a conquistador and the Indian -- as a Hispanic.

Is that what Hispanic means to you?

I love that word "Hispanic" because it introduces a paradox that I live with: I live in an English-speaking world but as a descendent of the Spanish empire. And as a gay Catholic. All these brown facts of my life, I've tried to record in some way, rhetorically, through a brown style.

You mention this tension of being two seemingly contradictory things -- gay and Catholic -- as well as Hispanic. What does this ultimately do for your American identity?

It could lead to a quandary and to a sense of deep confusion. At some level, especially after Sept. 11 when the book was nearly complete, I did have the sense that brown might become a very dangerous color in the future. Osama bin Laden is a brown man in the way that I was trying to describe, not simply in his pigment. He was raised a cosmopolite. There he is in Vanity Fair at the age of 14 with his extended family, standing in front of the Beau-Rivage Hotel in Geneva, speaking French, smiling for the camera. And then two years later we learn that he doesn't want to be that, he wants to be only one thing, in a cave with other men who are exactly like themselves. There are indications throughout the world and in this country too that there are people who will react against their brownness by denying it and by trying to make the crooked line straight within themselves. For that reason, it could be a dangerous time.

But for me, the creativity of the moment is exactly announced by the woman who writes to me and tells me that she is the daughter of a New York Jew and an Iranian Muslim. That there are Jewish Muslims in America strikes me as a very interesting thing and potentially very creative. We're already tasting that on our plate -- Chinese Italian food at some chic SoHo restaurant. But what we are only tasting, we have yet to announce in any formulated way. A woman tells me that she's Korean-African, and then she tells me that's not even the half of it, she's a Baptist Buddhist. I tell that to a theologian friend of mine in Seattle and he says that's impossible. And I said, "But she walks, she exists, and somehow we have yet to hear from her."

And so is that why you say that the ability to talk about miscegenation is such a freedom, or so important?

In America, we have never been candid about the force of eroticism in our history. Maybe because our whole endeavor was individualistic and not communal. Latin America, by comparison, for all of its races -- racism in some ways is more intense there than I've experienced in America -- has always had a vocabulary for the various possibilities that exist when people meet and create children that have never existed before. But in the United States, Halle Berry wins the Academy Award and we're not able to say, to this day, that she is a mulatto, which Latin Americans would say quite plainly. There is this reticence and when someone breaks out of that, like Tiger Woods, for example, there is this sense that he is trying to deny or avoid something. The Latinization of the United States, which is proceeding, is going to come in this way -- toward a more playful and vivid notion of brown.

But all this resistance goes back to the one-drop-of-blood rule of racial identity, doesn't it?

Yes, the great scar and great guilt of America was slavery. The profound struggle of African-Americans to overcome the original sin of this country was always written within this black-and-white dialectic. Obviously, the one-drop theory was a part of this -- who was an African-American? -- in a country where people were beginning to melt. The absurd Jim Crow notion that if you had one drop of African blood you were black -- what that did for those of us who were not African, but were brown, was very peculiar.

What do you mean?

The whole experience of growing up brown in this country, where one felt this incredible sense of irrelevance. That little ditty that I used to hear as a boy -- "If you're white, you're all right, if you're black, stand back, if you're brown, stick around" -- at once you were completely free because you were outside the main conversation of America, but you were also irrelevant to it.

I remember playing with my cousin, whose father was from India and mother was from Mexico, about what she was. We decided one day -- we were children -- that she was an Indian Indian. That was the beginning of my knowledge that there weren't names for what was coming, this new brown meltdown.

And when you were young, you looked to black writers for a sense of identity. Or what were you looking for?

Fundamentally, I was looking for an understanding of myself, but as an American, which is to say I was looking for the most profound story of America. It seemed to me that within the struggle of African-Americans to secure their full freedom in this country, every one of us was implicated. I know some people have found it odd that at an early age I was preoccupied by not Mexican writers, but with the struggle of African-Americans. But there it was. It was the great story of my generation.

Ultimately, it implicated me because the strategies for alleviating the effects of anti-black racism in this country -- namely, affirmative action -- were extended to people who were not black and to me, a so-called Hispanic, in the 1970s. I became a beneficiary of all that, of all that suffering, of all the demonstrations, of the water hoses and of the bulldogs, and the violence of those years and the determination of a people to stand straight. I, brown Richard Rodriguez, son of Latin America, became the beneficiary of all that, which is the irony of my life.

And obviously you've had a problem with this for some time.

I left the university over the issue of affirmative action and I've always felt deeply ambivalent about that because I don't qualify in any way as someone who was the primary victim of racial discrimination in this country.

How do you mean?

I wasn't. I had a very light-skinned father who looked more European than not. My mother is more Indian-looking. But at a very early age in Sacramento when the family became middle class, we were invited not to be Mexican. The neighbors would start insisting to us that we were Spanish. My mother would always say, "No, no, we're Mexican." But in many ways it was clear to us that we were given a way out. In no sense was I held back by discrimination. I just wasn't.

So why do you believe that it's irresponsible for the federal government and the media to keep saying that Hispanics are replacing blacks as the largest minority in America?

It's not only irresponsible. It's outrageous. It seems to me that we do not replace African-Americans. I owe my existence to African-Americans. I mean that literally. I owe the fact that I have this voice, this determination and this confidence in America to their story, to their lives, to their voices. There is no one who speaks American English who is not indebted to the cadence of their voices. The notion that I replace them is ludicrous. And the notion that one group, which is based on ethnicity, Hispanics, replaces a group that is based on blood or race, African-Americans, is really oranges and apples. It is profoundly disturbing to me that we so misunderstand A) the long heritage of African-Americans and B) the ultimate significance of Spanish in this country, which will be not racial but ethnic.

Is this because we look at groups simply in terms of numbers and population without being sensitive to what "minority" implies?

Yes, that's exactly right. We've only used the term "minority" in a numerical way. I become a minority when I get a job at a newspaper because I am numerically underrepresented, but no one ever asks whether I'm a minority culturally, that is, do I see myself or do I feel myself culturally to be in a minority within the society that I live in? That difference made it possible for middle-class nonwhites in this country to advance as minorities numerically, when they were not cultural minorities. It really fudged the issue; not only did the middle class advance on the backs of the poor, but also we've allowed ourselves to ignore the situation of poor whites because they are not numerical minorities. They are in some sense represented in the New York Times or in the White House, but I keep saying to people, "In what ways are Appalachian whites represented in the New York Times?"

How can we avoid this, though? You acknowledge that race is at the center of everything in America. You want to move beyond race entirely then?

Oh yes, I intend to undermine race with this book.

Is that possible? Or are we already in the process of doing that?

Well, here we are, 36 million Americans who describe ourselves outside of a racial category. We describe ourselves as Hispanic or Latinos. That is not a race. When my mother watches Spanish-language television like Telemundo, she watches a show called "Cristina." There's this blond woman Cristina in Miami with her audience and we see there are blacks in the audience and whites in the audience and brown people of various mixtures in the audience. And my mother says, "Son Latinos" ["They are Latinos"]. She doesn't say, "Oh there's a black man and there's a white woman." By virtue of the culture -- which is to say the language in this case -- she identifies them as all belonging to this term called "Latino" or "Hispanic." That is radical. And no one has really understood the effect that has on so many people. Sammy Sosa is as legitimately Hispanic as Madonna's daughter, and in that sense we are undermining the whole notion of race in America.

In "Brown," you say that, historically, whites define themselves against their perception of black identity. How do whites define themselves in relationship to the idea of the Indian, or a brown person?

It seems to me that whiteness became a kind of freedom, and a kind of emptiness too. A woman called me yesterday when I was on a talk radio show -- she lived in Canada and now lives in the United States -- and she said when she was in Canada, she had an identity. She was Irish, Danish. Now she's come to the United States and she's only white. She has no identity. She's a blank slate. And I told her that that's a kind of freedom. What I hope for African-Americans, as indeed for myself, is the white freedom to play black music, or to eat Mexican food, or to leave one's ancestry behind in New Jersey, to do whatever you want in America. Blacks never had that kind of freedom and it seemed to me there was always this restriction of the black that has now become in some sense self-imposed.

I was just going to bring that up. That's quite a barrier to moving beyond race.

Yes, African-Americans, for example, criticize each other for straying too far from what is acceptable. I've heard teenagers do this to each other -- "You're talking white."

As far as the Indian ... it seems that within that original triad, the Indian represented the elusive figure for the so-called white. The figure of wildness. Appropriately so, when the mythology also assumed that the Indian was dead and, therefore, in some sense, the white men replaced him. Forget the fact that Indians are very much alive in this country and that a lot of them are coming from Latin America speaking Spanish. But within that mythology there was a sense that to be part Indian -- even Bill Clinton claims to be one-sixth Indian -- was never the same problem, rhetorically, that being part African would have been. The connection to the land and entitlement to one's place in America ... the Indian really had a different station within the whole romance of America. To belong to that was to claim some part of the land.

How do you see blacks and browns interacting with each other in this triad?

We're in furious competition. For example, in Los Angeles, these demographic changes have created enormous dislocation for African-Americans. All the black neighborhoods in Los Angeles -- Watts, South Central -- these are all suddenly becoming Spanish-speaking and Hispanic. You saw in the recent election in Los Angeles a very reputable Mexican-American candidate who was just narrowly defeated, largely because the African-American population voted against him. And they voted against him, in part, because there was all this drumbeat in Los Angeles about how Latinos are the sleeping giant, waking up and taking over the city. It was incumbent on African-Americans to say, you know, we are still here. We matter. We are not being replaced. There's a lot of tension of that sort in this country. Liberals don't like to talk about it because it doesn't fit into their notion of the happy rainbow.

Incidentally, there was a riot in Riverside County a few years ago between Hispanic students and black students at a high school. Hispanic students were protesting the fact that Latinos only get one week for history week, and African-Americans get a whole month. Obviously, Hispanics need more history lessons because not to realize that they are already part of African-Americans' history is to misunderstand the meaning of their own Hispanicism. These are not separate groups. We are African. It is part of what it means to be Hispanic.

What sort of books do you think young Hispanics will look to? Will they seek African-American authors for ideas about identity? Or only Hispanic authors?

Certainly anyone coming of age in later years tended to be compartmentalized, as I am indeed compartmentalized on bookstore shelves as a separate department altogether. And the very writers who created me are in their own little department. They're on another side of the bookstore. That's what I resent so deeply, the turning of literature into sociology.

How does this miss the point of literature? What is the point?

To connect you to lives to which you do not belong. The notion that all literature is a kind of membership club that mirrors your face or your sexual orientation or your handicap is an absurdity. I gave a reading at the University of Arizona and the lesbians are waiting for the lesbian poet and the Mexican-Americans come to my reading and never the twain shall meet. It is so antithetical to everything that I loved about literature.

I read in the Washington Post that you've stopped reading fiction. Why?

There were suddenly a lot of unfinished novels around my bedroom. Maybe 10 years ago or so. I just lost an interest in narrative. I still don't understand exactly what that is but in some sense as I developed as an essayist, nonfiction seems to me more urgent, more interesting as a reader, as well as a writer. For example, when there are writers who write both fiction and essays, I tend to prefer their essays. James Baldwin, for example. None of James Baldwin's novels, with the possible exception of "Giovanni's Room," are as interesting to me as his essays. Or Joan Didion. I just can't finish her fiction, whereas her essays are absolutely wonderful. I always yearn to sit next to Joan Didion the essayist at dinner parties in Santa Monica or on the Upper East Side, but I always end up sitting next to the Joan Didion novel-heroine, who instead, has just had a nervous breakdown.

Does this have to do with something about contemporary fiction in particular?

No, because it's as true about 19th century [novels]. It's something to do with the clanking of narrative. I could hear the devices clanking away. I just knew, "Oh God, now I have to be here for 300 pages of this." And it was also that I belong to an age where we have almost too much narrative. There are too many stories; what we are interested in is what the story means. Which is why in our graduate schools of literature, no one reads novels. They only read critical theory. All of my friends who are in analysis have plenty of stories to tell, but they have to hire somebody to tell them what the story means. There's that movement to try to deconstruct or decode or make sense of narrative. And in that sense, I think the essay is very much alive because the essay really engages the history of an idea. Within the essay, I dramatize how I come to know something. It becomes a kind of intellectual diary.

Let's move to Richard Nixon. I was surprised, as I'm sure many people were, to read that you identified with him. Was that it, though? You identified with him?

Yes. I love Richard Nixon. What I knew that night when I was watching him sweat on that first televised debate was that Whittier College [Nixon] would always be defeated by Harvard College [JFK]. That the game was fixed in America. And I knew that in the same years that I was going to professional wrestling matches -- that the whole thing was fixed. Columbia University and the New York Times are all in cahoots -- the whole game is fixed. Kennedy wins the Pulitzer Prize for a book that he may or may not have written and there's nothing to be done about it.

There were always those nights in Sacramento at the wrestling matches, when I used to go by myself in my Boy Scout uniform, and the crowd would move its affection away from the hero because we sensed at that moment that he was the villain. He was the liar because the game was fixed, but he always pretended to be virtuous. Whereas Gorgeous George, the bleached blond villain, was in fact telling us something true about himself -- that the game was fixed.

There was something about Nixon, his insecurity, his ruthlessness and his crudeness that always struck me as true in the same way, in a way that the Kennedys never satisfied me. They always seemed, in their noblesse oblige, to be spooky people.

Then, Richard Nixon becomes my godfather and teaches me how to cheat in America by playing at being Hispanic. Richard Nixon the Californian -- perhaps wanting to undercut the black civil rights movement, but nonetheless begins to describe America in color, as white, black, Asian/Pacific Islander/yellow, American Indian/Eskimo/red and Hispanic/ brown. It is under Richard Nixon's administration that the whole spectrum now exists. After Nixon, it becomes easier for people to say that you have an ethnicity, you are Hispanic, you are Latino.

I thought you were against those classifications, though.

I disagree with it, but in its acknowledgement that we do not live in a 1950s television world of black and white, it seemed to me that Nixon was saying something important. In actual fact, though, I consider myself brown -- of all colors. Brown is not a singular color; it is the metaphor of impurity. By saying that I'm brown I'm saying that I'm Chinese, that I'm Irish, and I have to mean that I'm African.

Did Nixon also have that impact on you because it touched on your sense of the importance of class rather than race?

I was moved by Nixon's story. And Benjamin Franklin was very important for the encouragement he gave me to strive and to strive and to succeed. That basic American narrative I got from Franklin. But it was Nixon's conniving and dark eyes that also told me about the scheming that goes on in America. And his willingness to betray his own memory of himself by anointing me Hispanic was part of the seaminess of the whole story. It's a very complicated affection I have for Nixon. That chapter is probably my favorite. I weep when I come to the end of it. It's so sad. It's sad the way that "Citizen Kane" is sad. There's a dark story in America. Nixon comes very close to telling it for me.

Toni Morrison said that Clinton was our first black president and most people took that as a tongue-in-cheek statement. You write that Bush is the first Hispanic president. What do you mean?

Texas is the first state that seems to be on a north-south axis in a way that New York isn't. Certainly the intellectual-literary New York that I visit is so preoccupied by London so as to be almost an embarrassment. Maybe the advantage Bush had of growing up in Midland and maybe because the long acrimony between the Mexican and the Texan had such a deep influence on the way Texans understand themselves ... in Texas, there is always the sense of the South and the North and the inevitability of that. And I think when George Bush comes up with solutions to our energy crisis that engage Arctic wilderness areas and Mexican oil fields, it's inevitable for him to think that way. Most other Americans still think on an East-West map.

And I really do think that he has a kind of physical ease of a sort that Clinton had with black audiences. I've seen Bush with Hispanic audiences, especially when he's allowed or allows himself to speak high school Spanish. There's just this kind of physical pleasure that he has with it. And it's true. It doesn't seem to me fake; it seems to me a true joy that he has.

You say that Americans care more about their future than their past and you seem to feel that this is a good thing. But don't you think that Americans' inadequate knowledge of their own history is a problem?

Certainly, I speak as a son of immigrants, but that was also a great joy in America that my father did not dwell on Mexico, that we didn't have to look back and that I didn't have to become my father. My father made false teeth for a living, that's what he did. I knew as early as I began to speak American English that that would not be my destiny, that I did not have to have this past, that the whole point of this country was culture and I could move into a new culture. Culture gap. Culture shock. The whole notion that you could change your life that way was really quite amazing to me as a child, which is why I turned to Franklin. He was the son of a man who made candles and the family was large and had no money to send him to school. He was apprenticed at a young age and it broke my heart because that wasn't what I wanted from Franklin. I wanted the reassurance of his success. A country that had no past meant that you didn't have to be mired in memory of grandmothers. It was free.

But still people of different backgrounds seem to look for or hold onto some sense of authenticity, which implies that they're looking for something in the past.

You may be onto something really important. This lack of a sense of history has allowed us a kind of romance with race and ethnicity that is fanciful. I did a documentary some years ago about America and teenagers and the past and all these kids who were announcing themselves as wanting to recover their history, as though it was some reassurance, when everything I've ever read about American history is an embarrassment. It's filled with tragedies of all kinds. The notion that we would study history in order to feel better about ourselves is just ludicrous. But we have this romantic sense because we know it so little, our past really seems noble.

I don't look to Aztec Mexico for any reassurance about my identity. I'm aware that Aztec Mexico was a decadent society; its bloodlust was so extreme that its ultimate sexual energy was its pursuit of death. There's nothing in that history for me that leads me to the romantic calendars that you see in Mexican restaurants with the Aztec, almost naked with the feathers coming out of his head, and the Aztec princess at his knees. Nothing of that is convincing to me. History is a terrible, terrible burden which we need to confront, but I don't think the search for authenticity begins there. In many ways, that's a false romance that Americans are engaged in -- by seeing themselves as black or white or Scottish or Mexican through this search for authenticity.

In the end, you have an optimistic outlook for this browning of America.

In many ways, I do, yes. "Brown" has allowed me to reconcile myself to myself, that is, to allow for the unevenness of my life, to allow for its contradictions, to not have to figure everything out in my life, to see it as whole rather than as partial. Maybe this is some wisdom of middle age too, but I realize now that life is uneven, that I will always be Catholic as inevitably as I will always be a homosexual, that I will always be at odds with my identity, that I will always belong in some odd way to Latin America and that I will always belong to this other place, this country that is not at all like Latin America. That I will have all of those identities and that I will live with them in a brown way. For a man who has struggled with this and has sort of turned his life into an odd exercise in self-laceration, it comes with some great peace, almost as though I don't need to write anymore.

It's interesting because you write that our sexual history had so much to do with the violence of our history -- meaning miscegenation and so forth -- and then in the end, you're saying that our sexual future might have a lot to do with reconciliation.

Oh, yes. My advantage as this gay little boy was to always know that the most dangerous thing I could say was "I love you." What I learned from that repression was to notice just how often it occurs in history and to always look for it, especially where it was never announced.

There's a woman who shows up at my family Christmas every year, this blond lady who comes with all my relatives from India. I keep bothering my mother, "Who is she?" and my mother says, "Why do you keep asking about her? She's married to your uncle's nephew. She met him at Berkeley when they were law students. That's who she is. What do you want to know?"

What I want to know is how did she come to be here? Where does eroticism take us? Where does desire take us? Well, it takes us to this brown Christmas with Dr. Gupta singing Hindu hymns over the turkey and my mother with her American English accented by Spanish. What I realize now was that that woman's blondness was not an exception to our brownness but was deepening our brownness, was darkening our brownness. Her very blondness was making our brownness deeper and richer.

Shares