Mick Jagger had a point when he announced "it's the singer not the song" -- the young Rolling Stones were perfectly content to beg, borrow and steal material their charisma machine could strut to. The songs of Bob Dylan, which at first were his career, are now reshaped nightly in performance by an artful renderer. And as a singer, Paul McCartney has never been anything but the lucky sod who gets first crack at all of Paul McCartney's compositions.

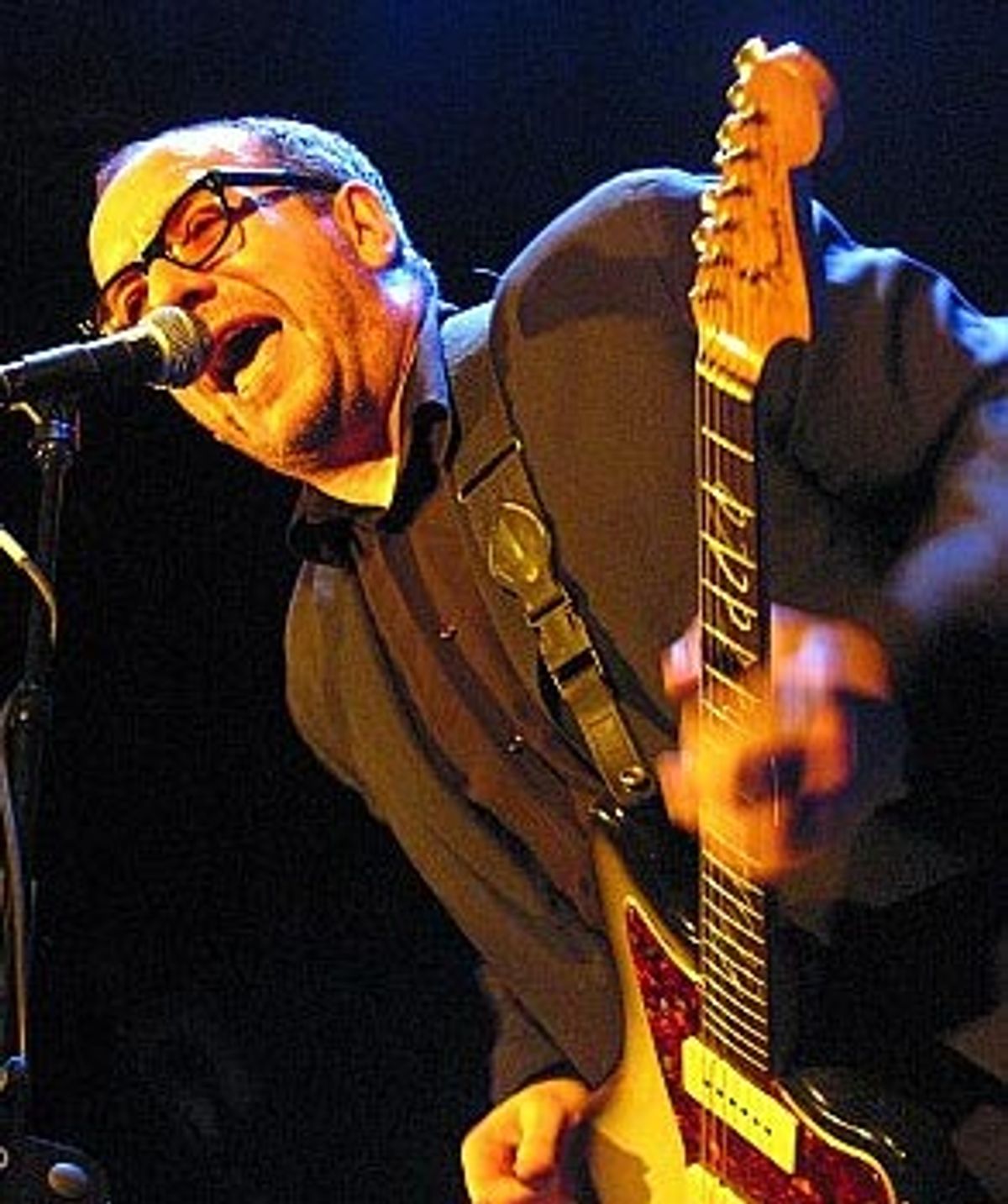

Elvis Costello has to have it both ways. He's a true singer-songwriter who respects both ends of that hyphen. For years, live and on record, this overachieving dynamo of lyrical and melodic invention took pains to serve up his bitter words with the choler of the freshly wounded. Later, when he outgrew rock to face the setting sun of pop gone by, he looked up Burt Bacharach to author a songbook of standards all his own. He didn't stop there. Without renouncing the excesses of his past, Elvis has become a subtle master of virtually any genre he fancies singing.

In 1993, answering a plea for one original tune from 15-minute British pop star Wendy James, Elvis banged out an album's worth in a weekend, scraps of brilliance delivered with the evident effort of a waiter clearing a table of spilled caviar. So inept was her handling of this bounty (no Jagger she), it largely escaped notice that E.C., in his distinctive and compelling style, had provided gimmicks and retreads -- more than adequate to her needs, but nothing he'd be bothered to sing on his own records. Had he kept them, other than a few standouts the songs might have made useful B sides, bonus tracks or shelf-sitters awaiting that extra jolt of ambition. Maybe artists as talented as Costello have trouble gauging the creative exertion each project demands. Maybe the line separating genius from hubris is hard to hold over time.

Writing songs for Wendy James was one of a sequence of events that led Costello to reconvene the Attractions -- the supple English trio that abetted Elvis's many moods until his need for new challenges became overwhelming in the mid-'80s -- for the potently invigorated "Brutal Youth" in 1994. Since then, Costello has primarily explored the land beyond rock, in collaboration with Bacharach, jazz guitarist Bill Frisell, opera star Anne Sofie von Otter and others.

All of this makes "When I Was Cruel" -- which begins brashly with "45," an acknowledgment of the artist's advancing age that cleverly fits 7-inch vinyl and the war years under the same numerical heading -- a significant test of Costello's ability to reinsert himself into the world he willingly (and not unwisely) left behind. If the preceding era didn't exactly spoil Costello for rock, it did leave that part of his muse a bit out of whack. "When I Was Cruel" is no great late addition to a brilliant career, no sudden burst of creativity in unexplored realms. "Stop me if you've heard this before," he sings in the cloying, overlong "Alibi," and those familiar with his work of the '80s will surely detect echoes of those years in nearly every song here.

The most compelling tunes, "Tear Off Your Own Head (It's a Doll Revolution)" and "My Little Blue Window," recycle the past to delightful effect, but that shouldn't be the best that can be said of a new album by an artist of Costello's caliber. In the shadow of a catalog containing such taut earthmovers as "She's filing her nails while they're dragging the lake," "Sometimes I think that love is just a tumor/ You've got to cut it out" and "Your mind is made up but your mouth is undone," there's not much to say about mundane choruses like "15 petals/ One for every year I spent with you/ Jewels and precious metals will never do" or "Well I believe we just/ Become a speck of dust."

The presence of keyboard player Steve Nieve and drummer Pete Thomas (who never got full credit for the tension and power of Costello's early records) only commits the Elvis youth reclamation project deeper to the past tense. (Davey Faragher, a veteran of Cracker and John Hiatt's band, does the Bruce Thomas bass parts here.) Singing with unabashed vigor, gamely chucking up doses of aggressive guitar distortion and a spot of squalling harmonica, Costello gives the old days another go. But other than testing his own mettle -- for whatever that's worth to someone who's written with Bacharach, covered Charles Mingus and sung for Tony Bennett -- what's it for?

There's more wrong here than the inevitable maturation of a no-longer-angry middle-aged man. No one is going to attack a happily married fella for loving his wife and singing about it. In his pop-crooner mode, love and loss are the language spoken, and a cutting remark would be gauche, but writing rock songs again sets him in competition with some of the smartest, most trenchant music ever written and recorded. The iceberg tipped by the euphoric rush of "Lipstick Vogue," "Pump It Up" and "Radio Radio" is a massive obstacle for this album to navigate. If the performances here reclaimed the sputtering, spastic fury of Elvis and the Attractions in their prime, it might not matter that Costello came to play without indelible melodies and jaw-dropping lyrics, but they really don't and he largely did.

The album's charms, which do exist, are slow to emerge. The seductively personal and disarmingly serious lawyer plaint "Soul for Hire" is sparely arranged with scraping sound effects to offset the vocal syncopation; "Daddy Can I Turn This" is oblique and ominous; "Radio Silence" is a solemnly played current-events coda in the vein of "Shipbuilding" or "Pills and Soap." But "When I Was Cruel" drifts more than it drives, jumping stylistic periods, with forced, graceless hooks and the sort of rote character studies ("Spooky Girlfriend," "Tart") his pop life might have rendered obsolete. "Dust 2 ..." and "... Dust" split one sentimental idea in two for no-waiting déjà entendu. While Costello is too smart for self-parody, "Episode of Blonde," with its lunatic lyrics and patches of Dylan shtick, comes mighty close, and "Dissolve" is essentially "5ive Gears in Reverse" without a melody. Even the album's centerpiece, "When I Was Cruel No. 2," stretches the gripping atmos-noir of "Watching the Detectives" into a lengthy bore.

Endurance presents a different challenge in rock than it does in jazz, blues or pop. Physicality, youthful allure and creative momentum are less relevant to the aging titans of those musics than to rockers struggling to beat the clock. Credible artistic careers of 30 or 40 years, the rule in many realms, are the exception in rock. Costello's reinvention as a vocalist was a prudent move, and this belated attempt to have it both ways is proof. If he hasn't lost the ability to rock with conviction, at the very least he's shown that it's no longer a simple matter of choice. "It was so much easier when I was cruel," he sings, and he's undoubtedly right.

Shares