For the last seven months we've been living in an era born from the destruction of buildings; in a way, few professions have been more profoundly affected by Sept. 11 than that of the people who design buildings for a living. Few architects, in turn, have felt a more personal connection to the disasters in New York and Washington than Cesar Pelli.

Pelli designed the World Financial Center complex in downtown Manhattan, a collection of foothills intended to soften and humanize the monolithic World Trade Center nearby. The four buildings, nearly 15 years old now, make up what critics have called the best urban space created in New York since Rockefeller Center. Now that the Trade Center is gone, the World Financial Center faces a future in a way Pelli never intended: on its own.

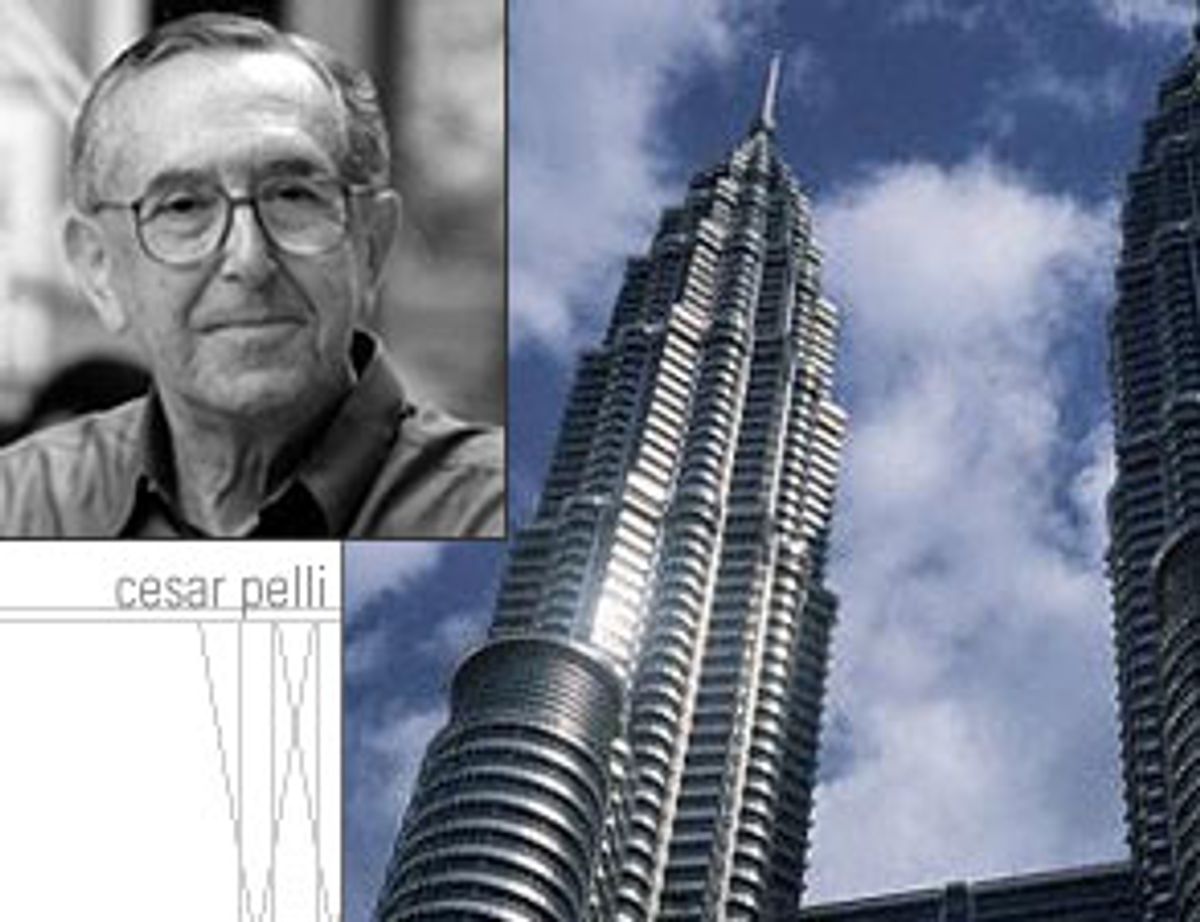

And there are other buildings for Pelli to keep an eye on: Completed just four years ago, his Petronas Towers in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, are now the world's tallest -- a title once held by the World Trade Center. He downplays any threats to their safety.

Born and raised in Argentina, Pelli got his start in the office of famed architect Eero Saarinen, working on such midcentury modernist classics as the TWA Terminal Building at New York's JFK Airport, and Morse and Stiles Colleges at Yale University. Pelli later served as dean of Yale's School of Architecture, and wrote the book "Observations for Young Architects."

Perhaps Pelli's greatest lesson has been his boundless passion for his work, which has kept him busy well into his 70s. He is the embodiment of Frank Lloyd Wright's assertion that all fine architectural values are human values. As we decide exactly what should rise from ground zero -- officials in New York recently announced they had accelerated the timetable for developing the World Trade Center site after criticism that the process was moving too slowly -- voices like Pelli's are all the more important. Salon recently spoke to Pelli by phone.

Where were you on the morning of Sept. 11?

I was in Washington, D.C. I had given a lecture the evening before at the National Building Museum, because there was an exhibition of my work scheduled. That morning when I was having breakfast a young lady came in with a very pale face and said, "Have you seen the TV? They have bombed the World Trade Center." So immediately I ran to the TV in my room. Unfortunately, I caught the second plane hitting the tower and both buildings collapsing, feeling total horror and disbelief.

Were you thinking of the buildings at a moment like that?

All I could think about was those images of people jumping from the upper floors. I knew that over 50,000 people worked in the World Trade Center, so I was watching this and imagining the many thousands of people that must be dying. At a time like that I was reminded how architecture is very unimportant compared to human life. There's no way I can understand in the slightest the state of mind that would possess people to do something so evil and on top of that to immolate themselves. How can man be so twisted?

What's it like for you seeing your World Financial Center buildings without the World Trade Center rising high above them?

I had never imagined them existing without the towers until Sept. 11. But as architects we try to create buildings that fit within their context yet would also be handsome in themselves. It's not as if you were removing one of the legs from a tripod. The aesthetic balance of the World Financial Center was always complete. They just were intended to be good neighbors to the towers.

How do you see downtown Manhattan now?

An interesting change has taken place. Up until Sept. 11, the World Trade Center towers completely dominated the composition. Now that they're gone, you realize that this is still a composition of very large buildings. They just don't seem so tiny anymore. In some ways, all of those other buildings have gained a great deal by being restored to their previous relationship to each other and the city. So I have real mixed emotions. Of course it was a terrible act that caused their disappearance. But beyond that, I have to say I believe downtown Manhattan looks handsomer and more humane than it did before.

How will it change the street-level urban setting?

The World Trade Center was for me not only out of scale vertically, but it was also out of scale in plan. It occupied several blocks that were all massed together. I hope they will not re-create that huge isolated parcel that was the World Trade Center. I hope that the streets will be reopened. Downtown is being transformed not just into a place for finance, but a much more complex working and living place. Look at the extraordinary success of a place like Tribeca. Those kinds of transformations I think are very good in a city. Something terrible has happened but you cannot go back. It's impossible.

You also designed the Petronas Towers in Malaysia, the tallest in the world. Is the era of the skyscraper over?

No, not at all. I think once the current threat is gone and we all feel comfortable again, the desire to build tall buildings will reassert itself. I believe that it's part of the nature of human beings. Very tall buildings have appeared in different forms and different guises throughout the world: pagodas, minarets, steeples, campanulas, solar symbols. I believe these styles will return, although unquestionably there will be a hiatus. Even aside from the fears we have at the moment, that's an appropriate act of deference to the terrible catastrophe that happened and the people who were involved.

What should be built at ground zero?

There is not a simple answer. I believe the only successful solution will be one that incorporates the feelings and thoughts of a variety of people, not only the key players like Silverstein and the Port Authority, but everybody in Manhattan who for any reason feels affected by what happened. I know that there are people who would like to build nothing at the site, to leave it as a memorial. Other people would like to build exactly what was there before. Between that I've heard almost every other option. From my point of view, I think a significant memorial is highly desirable. The footprints of the two towers have become hallowed ground. It would be very strange to propose buildings there.

Do you believe Sept. 11 was a watershed moment in architectural design?

No, I believe that while it made a terrible impact and we're greatly moved, I don't expect any particular effect in how architects approach design. There may be some changes in building codes, but I don't see any stylistic departure that you'll be able to attribute to Sept. 11.

What about the trend in architecture that was already happening, the end of postmodernism in favor of a renewed taste for the modernist tradition of Ludwig Mies Van Der Rohe and Louis Kahn?

I would not describe it in the terms you have. Clearly the kind of postmodernism that was at heart a caricature of historic styles had a short life, and it's wonderful that it is gone. But what we're seeing now is only superficially related to traditional modernism. There are a number of architects doing very idiosyncratic, individual forms. That's something that modernism was definitely against. Modernism called for architecture at the service of society, not of the people who design them.

Speaking of which, do you think the international market for "signature" architecture sparked by Frank Gehry's Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, ended with Sept. 11?

I don't think Sept. 11 will affect that particular trend. I think it's something else. Frank Gehry really had a wonderful building in Bilbao, and it's also a great tool for attracting a kind of tourism that city didn't have before. But I believe many other institutions and places that are trying to repeat this are going to be very disappointed. The kind of architecture that Frank does is extremely difficult to pull off. Plus with today's economy it's more difficult. Unquestionably there is a great demand for signature buildings. But like all fashions -- and this is unquestionably a fashion -- it will pass.

Unlike Gehry, you don't have one identifiable style. What's your approach to design?

I realize that having a style would be very beneficial for my practice from a marketing standpoint, but I can't do it. I believe my responsibilities as an architect are to design the most appropriate building for the place. Each place has a distinct culture and function, which for me requires an appropriate answer. I need to design a building that fits there very well.

I will say that that's also one of the great things about the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao. That building fits in that particular place where Frank put it extremely well. I've seen designs by other architects who are trying to do something as idiosyncratic and artistic as Frank Gehry, and they don't fit very well. They stick out like sore thumbs.

How does being an immigrant affect your outlook in the United States?

One of America's strengths has always been its openness to the new: both new ideas and new people. We may see a slight slowdown in immigration temporarily, but I think we will and should continue accepting new people and new ideas. I don't see a long-term change to immigration. People may need to bring more documents and prove more things in order to get into the country, but those are things we can put up with under the circumstances.

Do you still enjoy practicing architecture as much as you did before Sept. 11?

Yes, I enjoy it all, every part of the process. For example, I just found out about half an hour ago that we've been selected to design some laboratories for the University of Houston. Oh, my God, it'll be fantastic in so many ways! It's wonderful how all the ideas develop at the beginning, and then the building starts taking form.

Sometimes getting to that point is difficult, because the forms and solutions that go into a building have to be just right. But when we come up with those correct ideas, and I think about the building performing for the scientists and the students there, it's just fantastic. And I love it when I go back 10 years later and people tell me about how happy they are.

You've been practicing architecture for half a century now. When did you first know you wanted to be an architect?

I was 17 years old. I had entered the School of Architecture in my hometown of Tucuman, Argentina, but I wasn't sure yet that I wanted to be an architect. This was a beaux-arts school, so we were doing lots of formal designs for temples and parapets and tombs and urns. I couldn't make any sense of how learning this would really help serve my hometown. Halfway through the year, though, some young architects came to the school and brought the ideas of modernism, that we could design buildings that would contribute something to making people's lives better: hospitals, schools, bus stations. Suddenly I realized that architecture could have a deep social purpose. That was a revelation to me, and I knew it was something I wanted to do for the rest of my life.

Shares