The reputation of Donatien Alphonse François, otherwise known as the Marquis de Sade, is much better known than his actual writing. Plenty of adolescents -- and a good many curious grown-ups -- have picked up his books hoping for a sizzling read, only to find themselves snoozing through the mighty, gaping spaces between the flagellation of buttocks and the cutting off of bosoms. That's not to say that Sade wasn't an interesting fellow, or that his work doesn't have anything to offer scholars: It's just that, for the rest of us, an old "Red Shoe Diaries" video is likely to get us hotter.

And so it was only a matter of time before someone reinterpreted Sade as a tasteful historical figure. It sure wasn't Philip Kaufman, in his wickedly saucy 2000 "Quills": Kaufman saw what was funny about Sade as well as what was twisted, and decided that more often than not, the two qualities were as intimately twined as the braided cords on a cat-o'-nine-tails. Geoffrey Rush, as Sade, wore the character's slumped, knackered-out old man's body as proudly as he did Sade's tattered finery. It was a badge of sorts, an assertion that he knew his appetites couldn't outlive his own flesh, and he wanted to make damn sure he was the first one to have a bitter laugh at it.

But with the new "Sade" (now playing in New York and on its way elsewhere), French director Benoît Jacquot genuflects so deeply and so reverently that you wonder if the real Sade wouldn't have kicked him over with a mighty cackle. The movie is as far as you can get from racy, to the point where it almost stops the blood flow to your brain; it has a dull, costumey feel.

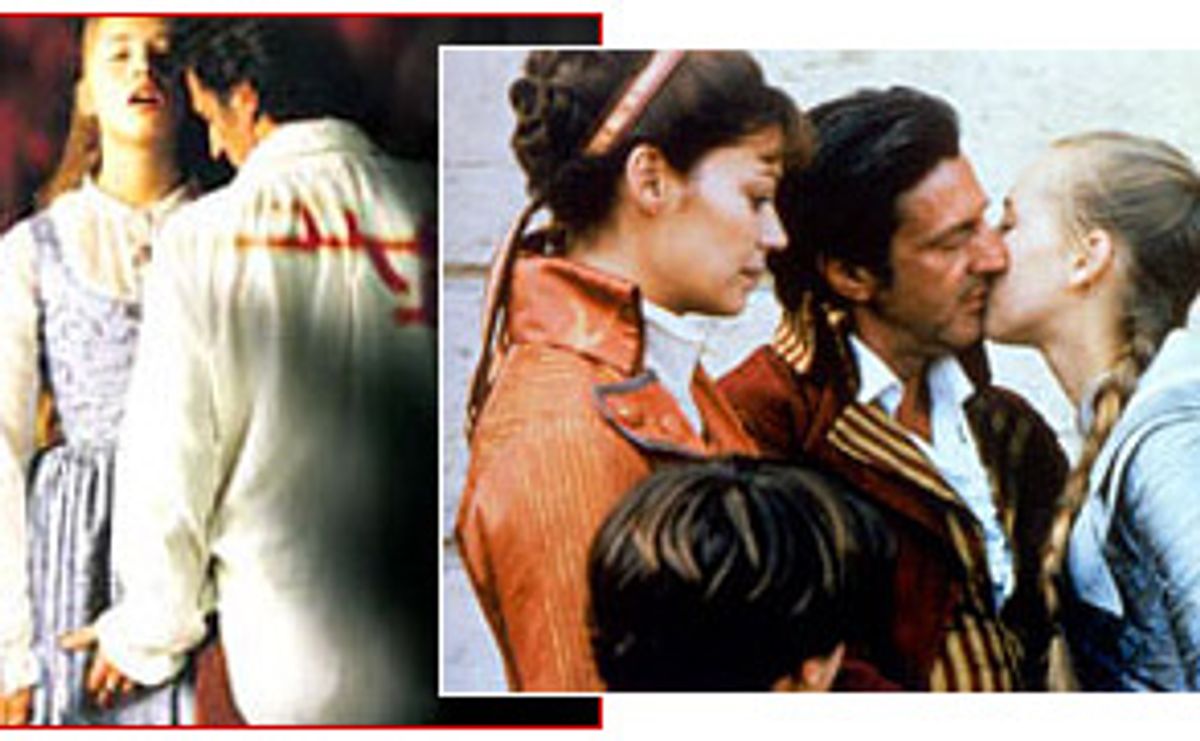

"Sade," with Daniel Auteuil in the title role, covers one portion of the Marquis' life, the time he spent in an upscale jail known as Picpus, hiding out from the Great Terror with other assorted aristos. There he tarries with Emilie, a persistently sullen blond teenager (Isild Le Besco, the hot French babe du jour, who can also be seen in "Girls Can't Swim"). He also receives visits and provisions (things like writing paper, good wine and alpaca sheets) from a woman he calls "Sensible" (Marianne Denicourt), with whom he has been involved. She's devoted to him, at least partly (but not wholly) because of the financial support he has provided to her and her young son.

The plot of "Sade" consists mostly of young Emilie's repeated and wearying trips to Sade's quarters (she has been forbidden by her parents to associate with him, which immediately gives him more cachet than Justin Timberlake), where he challenges her with brain teasers in an effort to warp her little mind. In every scene, Le Besco wears the same expression of sullen teen contempt born of nothing but bored self-absorption. When Sade wisely refuses to let her read the manuscript he's scribbling away at, she pleads and begs; he relents. We see her reading the words, first with curiosity and then with disgust, until, as if on cue, she flees the room as fast as her little silk slippers can carry her. You'd think he'd asked her to touch his thing! But no, that comes later.

So, naturally, she comes back. Over and over again. You can't really blame her, considering that neither Jacquot nor Auteuil has succeeded in making Sade seem particularly dangerous or predatory. Twice we see him setting a large black carved dildo, resolutely, on a tabletop. Sacre bleu! The man is a fiend! Similar silly curlicues of shorthand pile up but don't add up to much. We're supposed to leave the theater having reached the sensible conclusion that while Sade may have been a perverted guy, he had some really cool ideas about the connection between cultivating a strong sense of self and getting one's rocks off.

Anyone who has read anything about Sade -- like Francine du Plessix Gray's delightfully readable "At Home With the Marquis de Sade," for example -- will suspect that Sade was a little more complicated than that. But Jacquot, working from a screenplay by Jacques Fieschi and Bernard Minoret (adapted from Serge Bramly's novel), is more interested in presenting Sade as the 18th century's most lovable libertine, a grand thinker whose unorthodox, tiger-size urges paled in comparison to his role as a fighter for personal freedoms. This Sade utters lines like, "What can I tell you? Yes, I was a libertine," and "I took the byroads when they wanted me to follow the highways." Just like Sinatra, he did it his way.

It's a minor saving grace that this Sade is played by Auteuil, who has been doing astonishing work these past few years, most notably in the otherwise lackluster "Widow of St. Pierre" and "The Lost Son," a finely wrought picture about a child-porn ring that was never released in this country. Auteuil has some terrific moments here, especially in his scenes with Denicourt (a marvelous actress with whom many American moviegoers may not be familiar, but whose work in pictures like Jacques Rivette's "Haut/Bas/Fragile" is worth seeking out; she also appeared with Auteuil in the "The Lost Son"). He's tender with her but also brazenly, hungrily sexual. Denicourt's catlike smile suggests that, even though she is respectable and kind, she meets him more than halfway.

Their scenes together are the most honest in the movie, and they're the only moments in which the picture burrows in any satisfactory way into Sade's character. That may be because when Auteuil shows us Sade's tender side, we can easily trace the arc to its polar opposite, his self-absorbed aggression. The Sade who loves Sensible is a much darker, more complex character than the one who philosophizes handily to anyone who cares enough to listen -- or even than the one who keeps a big black dildo on his desk.

If you're looking for thrills, you should know that you have to wade through a good seven-eighths of the movie before Sade does anything remotely disreputable, and even then it's a rather mechanical bit of business that would have been more effective (and more disturbing) if it had been handled with a bit of humor.

But then, humor would have interfered with Jacquot's obvious goal of making a certified thinking person's movie. If only the director had paid more attention to Sade himself, who says right there in the movie, while educating the eminently innocent Emilie, that he has never made a distinction between the mind and the body. To demonstrate, he points to la tête and then grabs le dick. It's the second part that Jacquot needs to work on.

Shares