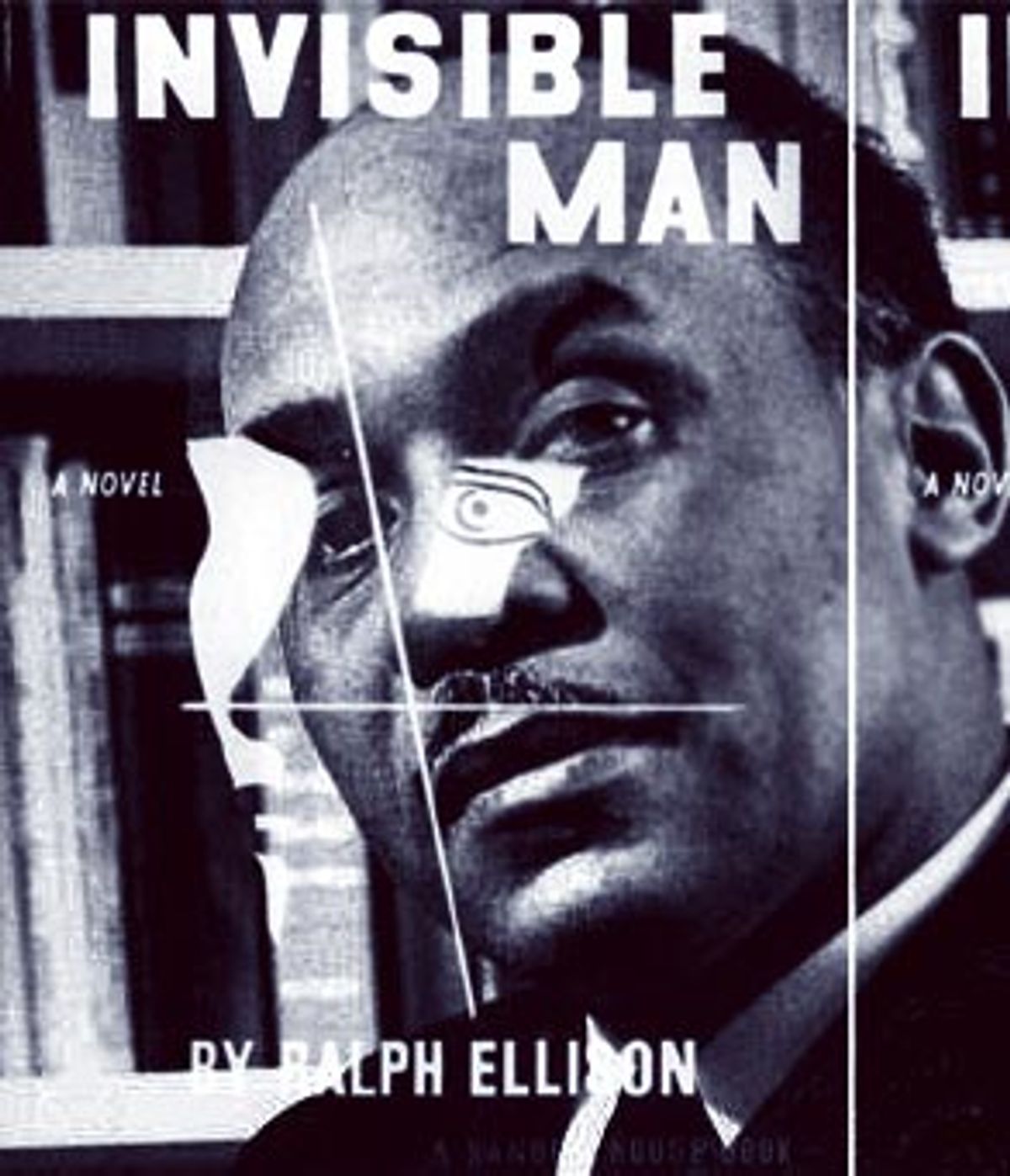

This year marks the 50th anniversary of Ralph Ellison's "Invisible Man," a sophisticated, allusive novel that captured the perennial human search for personal identity through the prism of a nameless black American character. Ellison intentionally created and crafted his protagonist so that, in the author's own words, the young man's "curiosity and blundering ... transcend any narrow concepts of race and hit us all where we live."

This quote, from a 1971 interview, says in direct language what is posed more quizzically in "Invisible Man," when the narrator concludes the epilogue by asking the reader: "Who knows but that, on the lower frequencies, I speak for you?" As we shall see, there are critics from the 1950s to the present who take exception to the notion of Ellison (or his fictional character) speaking for them. They, for various ideological reasons, claim that his vision is inadequate and that he was too politically disengaged or conservative.

In terms of widespread readership and critical acclaim, however, Ellison's first and only finished novel spoke with eloquence to many. "Invisible Man" was a national bestseller for 16 weeks after its publication in April 1952. It won the 1953 National Book Award for fiction, has been translated into 17 languages and has never been out of print. In 1999, a group of prominent writers and scholars placed "Invisible Man" in the top 20 list of the most influential fiction from the 20th century.

Yet from the start the novel and, later, its author attracted criticism from a wide variety of sources. In a recently aired documentary entitled "Ralph Ellison: An American Journey," broadcast nationally on PBS stations under the American Masters banner, writer-producer-director Avon Kirkland brings many of those complaints to light yet again. The poet and playwright Amiri Baraka (formerly LeRoi Jones) appears in the film, calling Ellison a snob, a skilled artist with "backward" ideas. A clip from the documentary, of Baraka screeching, "Come on out, niggers, niggers, niggers, it's nation ti-i-iime, it's nation ti-ii-ii-im-e!" is perhaps enough to discredit him in the eyes (and ears!) of many viewers. Baraka's stances have, since the '50s, been as a beatnik, an anarchist, a black nationalist, a radical Marxist and God knows what else. More than a few backward ideas adhere to this miasma of ideologies.

Jerry Watts, an author of critical texts on Ellison and Baraka, repeats the claim that Ellison, by attempting to transcend American confines, divorced himself from the collective struggles of black Americans. Although in the film African-American scholar Cornel West praises Ellison, when I asked West what he thought of the author several years ago at a public forum, West dismissed Ellison as a "highbrow aesthete." In a recent book, literary scholar Houston Baker, former head of the Modern Library Association, calls "Invisible Man" "Disneyesque," "a novel of American local color in its comically best minstrel manifestation ... the panoramic, black dis-empowering, white-reassuring view of race matters that 'Invisible Man' offers is exactly what white America always welcomes."

As I mentioned above, such sniping isn't new. Upon the publication of "Invisible Man," Communists and fellow travelers objected to its depictions of the Brotherhood, a doctrinaire, utopian, Marxist-style organization that uses social unrest in Harlem and the protagonist's passion and naiveti to further their own cause. When orders come from the Brotherhood's party leadership to change strategy and tactics, those orders are to be followed, not questioned. As did his friend and colleague Richard Wright, Ellison had direct experience working with Marxist publications and organizations in the 1930s, though he, unlike Wright, never was a card-carrying member of the Communist Party. Wright's "American Hunger" relates how the party "disciplined" those who were too "individual" in their thought. Likewise, Ellison's Brotherhood is interested only in the fulfillment of its political objectives, through blind loyalty if need be, and not in the Invisible Man's intellect, identity or culture.

Black nationalists were miffed at the character of Ras the "Exhorter/Destroyer," a rabble-rousing West Indian "community organizer" who views the world in "Invisible Man" almost exclusively through the lens of race. Ras is ready to resort to violence against his foes, black or white, to achieve his separatist goals. Even today, black nationalists are wary of Ellison's work; to them, it's too pro-American, and too inherently critical of their narrow or romantic preoccupations with Africa or with the blackness of blackness. Echoing Houston Baker above, Molefi Asante, perhaps the leading proponent of Afrocentricity, wrote in 1990 that Ellison's "aim is to write to a white audience, to show them the invisibility of the African -- if possible to create thought, guilt, understanding, liberation for the white man."

Others criticized Ellison himself for his seeming lack of active involvement in "the struggle." Few are aware that Ellison belonged to the Committee of One Hundred, an arm of the legal defense committee of the NAACP. He served for nine years on the Carnegie Commission on Educational Television, whose findings led to the formation of public television. He served as a charter member of the National Council of the Arts; he served as a witness at a Senate subcommittee hearing on urban issues in 1966. Yet even if these facts were not brought to bear, Ellison's true allegiance to the "struggle" remained a given, for the struggle includes and at the same time goes beyond the black American battle for justice. Ellison realized that the "struggle" is ultimately a fight over defining and improvising reality, and as such includes matters intellectual and aesthetic as well as political and economic.

Ellison resisted the kind of demands often put on artists because of their membership in particular groups. In fact, he considered art that placed politics before artistry not merely unfortunate, but actually inadequate and wrong. His nonfiction writings (many of which can be found in the Modern Library's "The Collected Essays of Ralph Ellison") provide an autobiographical and aesthetic context that frames this point of view. For instance, one theme that runs throughout Ellison's work is the correlation between morality and craftsmanship. In a 1973 Washington Post interview with journalist Hollie West, Ellison said, "If you describe a more viable and ethical way of living and denounce the world or a great part of society for the way it conducts its affairs, and then write in a sloppy way or present issues in a simplistic or banal way, then you are being immoral as an artist."

Ellison's perspective on the ethics of craft and technique wasn't based simply on aesthetic theory: It was a matter of personal, life-and-death experience. He compares the bad writer who lays claim to readers on the basis of his race or politics to the bad doctor who misdiagnosed his mother's tuberculosis of the hip as arthritis, an incompetence that led to her death: "A physician who insists that you patronize him because he is a black physician and then he has not mastered his craft, then he is immoral and he leads to the destruction of life ... Writers who are supposed to present visions of the human condition which will lead to some sort of wisdom in confronting existence or experience and who do not do that in a disciplined and informed way are immoral."

This isn't to say that race wasn't one of Ellison's perpetual themes; it's just that he placed more value on culture than on race. The lifestyles and traditions of black Americans are, in Ellison's eyes, much more than a sociological tale of unremitting woe, misery and defeat. The story of American blacks, central to the nation's struggle to realize its democratic principles, represents a heroic instance of a supremely creative response to social and economic repression. This is a story Ellison saw echoed in such characters as James Joyce's Stephen Dedalus. In "Invisible Man," Ellison wrote: "Stephen's problem, like ours, was not actually one of creating the uncreated conscience of his race, but of creating the uncreated features of his face ... We create the race by creating ourselves and then to our great astonishment we will have created something far more important: We will have created a culture."

And, as he put it in a 1961 interview with Richard C. Stern, "You know, the skins of those thin-legged little girls who faced the mob in Little Rock marked them as Negro, but the spirit which directed their feet is the old universal urge toward freedom. For better or worse, whatever there is of value in Negro life is an American heritage, and as such it must be preserved."

What, apparently, Ellison's critics don't understand is his adherence to a distinctly American notion of freedom, closely allied to the jazz musician's imperative to find and maintain one's own voice. He did not want to be a spokesman. From the same interview mentioned directly above, Ellison avers that rather than writing propaganda, "Instead I felt it important to explore the full range of American Negro humanity and to affirm those qualities which are of value beyond any question of segregation, economics or previous condition of servitude." Although some of his early nonfiction writing can be legitimately called propaganda, the mature Ellison refused to cast a shadow on his artistic integrity by engaging in agitprop because, to him, a writer bending "to some ideological line" actually limits both himself and the group because by doing so he deprives the group of the writer's uniqueness.

Even liberals quarreled with Ellison. Critic Irving Howe, for instance, took issue with "Invisible Man," calling it "literary to a fault." In the essay "Black Boys and Native Sons," Howe wrote that authentic black writing would focus on characterizations like that of Bigger Thomas in Wright's "Native Son," one in which embattled bottled rage boils over: "How could a Negro put pen to paper, how could he so much as think or breathe, without some impulsion to protest ... the 'sociology' of his existence forms a constant pressure on his literary work, and not merely in the way this might be true of any writer, but with a pain and ferocity nothing could remove."

Ellison took exception to this constricting notion of authenticity: "Note that this is a condition arising from a collective experience which leaves no room for the individual writer's unique experience. It leaves no room for the intensity of personal anguish which compels the writer to seek relief by projecting it into the world in conjunction with other things ... nor does it leave room for the experience that might be caused by humiliation, by a harelip, by a stutter, by epilepsy -- indeed, by any and everything in this life which plunges the talented individual into solitude while leaving him the will to transcend his condition through art."

"Evidently," he continues, "Howe feels that unrelieved suffering is the only 'real' Negro experience, and that the true Negro writer must be ferocious. But there is also an American Negro tradition which teaches one to deflect racial provocation and to master and contain pain. It is a tradition which abhors as obscene any trading on one's own anguish for gain or sympathy; which springs not from a desire to deny the harshness of existence but from a will to deal with it as men at their best have always done. It takes fortitude to be a man, and no less to be an artist. Perhaps it takes even more if the black man would be an artist."

Ralph Ellison's cultural project, with regard to America, was to "explore it, create it by describing it." This endeavor may not satisfy his naysayers. Nonetheless, their most incisive rejoinder may have been published in 1967 by Harold Cruse, who in "The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual" wrote of a left-wing group that could not "attack Ellison on craftsmanship, or even content anymore ... because none of them has written anything even remotely comparable to Ellison's achievements. Hence they must assail him on the question of participation in the 'struggle,' and the fact that Ellison once stated that art and literature are not 'racial.'" True then, true now.

Shares