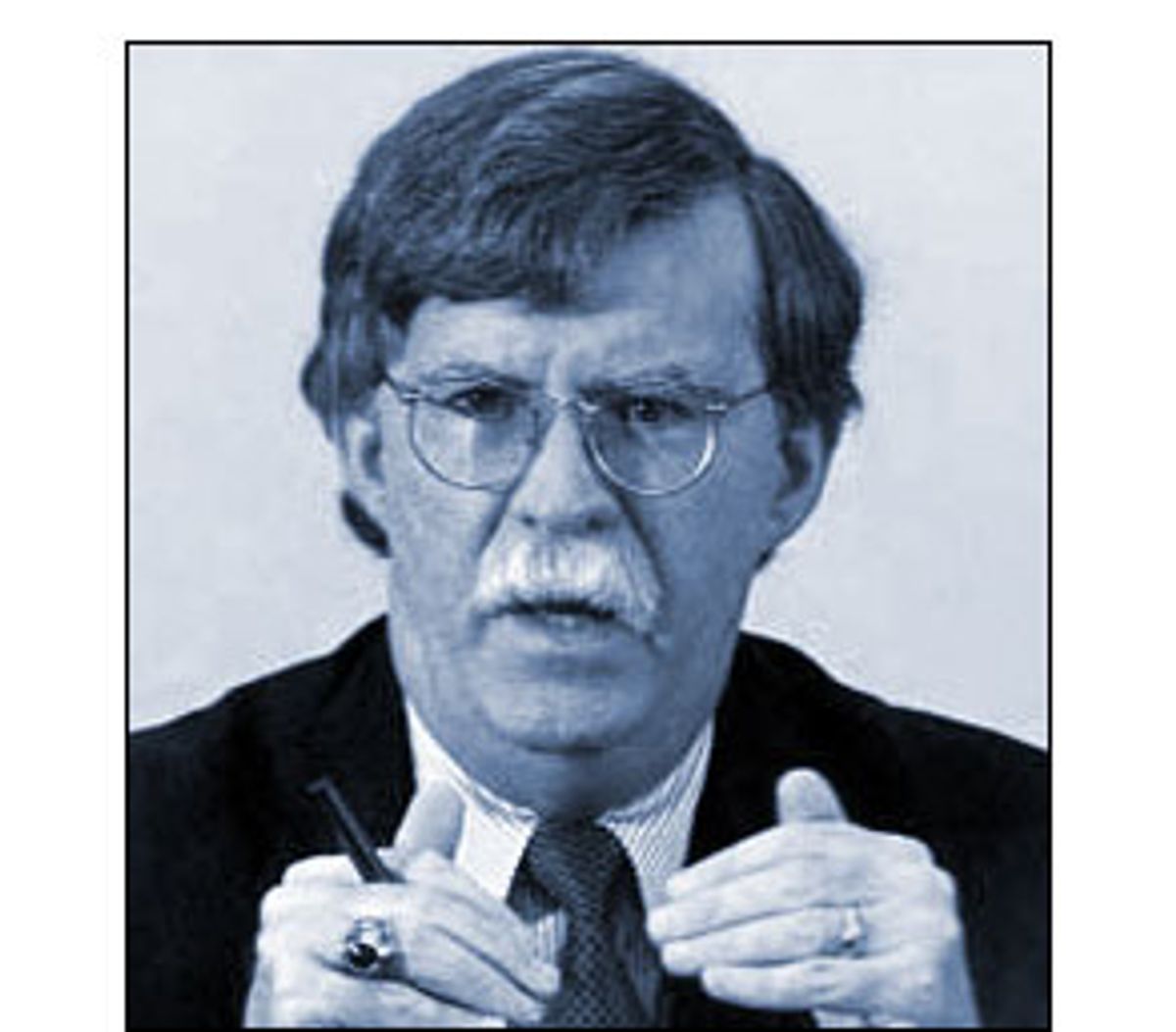

Monday was a busy day for Undersecretary of State John Bolton. In a speech to the conservative Heritage Foundation, he added new enemies to the administration's axis of evil hit list, telling the audience that Cuba, Syria and Libya had joined Iran, Iraq and North Korea as enemies and evildoers extraordinaire. That same day, Bolton sent a letter to the United Nations reversing President Clinton's decision to back the founding of the International Criminal Court.

The U.S. "does not intend to become a party" to the International Criminal Court, Bolton wrote, and therefore "has no legal obligation arising from its signature" on the Rome statute that established the ICC.

Reversing the ICC agreement was a strange role for Bolton, since as undersecretary of state for disarmament affairs and international security he does not exactly have the court in his bailiwick. But the busy Bolton has never let his job title blunt his ambition, and he has emerged as an energetic force trying to return the Bush administration to its pre-Sept. 11 habits of unilateralism, thumbing its nose at the rest of the world.

Bolton's usurping the ICC decision would seem to mean that he is successfully building a power base for unilateralism in the State Department, which his allies on the right have traditionally regarded as the bastion of soft, liberal multilateralism. At the time Bolton was appointed, Beltway scuttlebutt held that he was forced on Colin Powell against the latter's (much better) judgment. Certainly their positions and styles are poles apart.

So who is Bolton, and is his growing power worrisome? It depends on what you think of Sen. Jesse Helms' political legacy. The two men share the same contempt for the United Nations, and most of the rest of the world. Helms has praised Bolton as "a treasured friend," "a patriot" and "a brilliant thinker and writer." He served in the first Bush administration, as assistant secretary of state for international organizations, under another key mentor, James Baker.

During the Clinton years, Bolton endured his exile as vice president at the American Enterprise Institute, the conservative think tank that has housed Newt Gingrich, Richard Perle, Jeane Kirkpatrick, Lynne Cheney and others. He can also play the good soldier, heading down to Florida in November 2000 to help the Bush team recount disputed ballots in Palm Beach, under the leadership of recount czar Baker.

And despite years of attacking the U.N. -- in 1994 he said, "There is no such thing as the United Nations" and "If the U.N. Secretariat building in New York lost 10 stories, it wouldn't make a bit of difference" -- he was not above becoming James Baker's assistant on the egregiously stalled U.N. mission to the Western Sahara in 1997. Nor did his contempt for the U.N. stop him from taking $30,000 from the Taiwanese to write position papers on how they should go about becoming members of the organization whose credibility and very existence he has questioned.

Those who saw him at work both at State and on the Western Sahara testify to his deep loyalty and admiration for Jim Baker, which has sometimes served to get him to moderate his views. Baker was pragmatic in the old-fashioned way of Texas oilmen: Sometimes there is oil under other countries and you have to cooperate with them to get your hands on it, even if you don't like them.

Bolton has been around for a long time, and normally shows little reticence in stating his worldview, always through a right-angled prism. However, he can be very pragmatic when it comes to getting jobs. His contested confirmation hearings last year were a classic case of confirmation conversion, where he managed to fudge and hold his tongue for the duration of the hearings, and not say anything too controversial.

Since then, Colin Powell has not had the same leash on his unruly underling that James Baker did. While Powell seems to think that treaties and allies should be taken seriously, Bolton subscribes to what he understands as the Bush doctrine. The U.S. should "recognize obligations only when it's in our interest," he says. "But if we sign a treaty, we'll abide by it." Still, he'd rather the U.S. not sign many treaties. And he told a recent conference that treaties are "law" for domestic purposes only, and that in their international operation, they are simply "political obligations," presumably ones that can be ignored when inexpedient. And as for allies, he has asserted that "the Europeans can be sure that America's days as a well-bred doormat for E.U. political and military protections are coming to an end."

Giving Bolton the title of undersecretary of state for disarmament had a seriously Orwellian feel: There's no doubt that he wants a U.S. armed to the teeth. Helms endorsed his nomination with unintended irony: "John Bolton is the kind of man with whom I would want to stand at Armageddon, if it should be my lot to be on hand for what is forecast to be the final battle between good and evil in this world." If Bolton has his way, there are serious grounds for thinking that Armageddon is closer than the rest of us would like.

After the Senate voted not to ratify the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT), he gloated "CTBT is dead," although polls showed that more nearly 80 percent of Americans support a ban on all underground tests. Bolton mocked supporters of the test-ban treaty as "misguided individuals following a timid and neo-pacifist line of thought." In an interview with Arms Control magazine, after taking office, Bolton caused a stir by seeming to back off the "no first use" of nuclear weapons doctrine that has been the underpinning of the nonproliferation treaty.

"There is an axis of undersecretaries like Bolton who out of office were doing bad things, and now they're in office are doing even worse things," complains John Isaacs of the Council for a Livable World. "We may get an arms control agreement despite the likes of Bolton, if the grown-ups like Powell get involved. Colin Powell is careful where he picks a fight, and so far, he hasn't on this. So the State Department has taken a lot of positions on arms control that seem strange considering who's secretary of state."

Sen. Byron Dorgan, D-N.D., vigorously opposed Bolton's nomination, and the statement he made at his confirmation hearing was prescient. "To nominate Mr. John Bolton to be undersecretary of state for arms control defies logic. The answer from the president, it seems to me, in sending this nomination to the Senate is no; we don't intend to lead on anything. We intend to do our own thing notwithstanding what anybody else thinks about it, and notwithstanding the consequences with respect to the reduction of additional nuclear weapons and delivery systems. Mr. Bolton's appointment is another sign of the president's hard line on these issues, as a unilateral policy to abandon ABM, or to get rid of the ABM Treaty, or ignore it, build a destabilizing national missile defense system, ignore the Kyoto treaty, abandon talks with North Korea, and oppose the international criminal court and the international landmine convention."

Indeed, all of Dorgan's predictions have come to pass. But Bolton will not rest on his laurels. He is part of the faction pushing plans to attack Iraq under cover of the war on terrorism. Given the lack of evidence of Baghdad's involvement in Sept. 11, Bolton and his friends fervently hope that Saddam Hussein will be stupid enough to continue to refuse U.N. inspectors to give them a pretext for their move. According to the Washington Post, Bolton had the CIA investigate Hans Blix, the former head of the International Atomic Energy Agency who is now head of UNMOVIC, the U.N. team waiting to go in when Hussein has a rational moment. Bolton was reportedly very angry when the CIA could find no evidence of sympathy for Hussein by Blix. He led a successful three month battle to overthrow Jose Bustani, the head of the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons, who was deposed in April for trying to get Iraq to sign the Convention on Chemical Weapons.

And he does not like U.N. Secretary General Kofi Annan much better than Saddam. In October 1999 he wrote a screed for the Weekly Standard, "Kofi Annan's UN Power Grab," where he alleged Annan was trying to limit warfare and to establish the supremacy of U.N. forces. "If the United States allows that claim to go unchallenged, its discretion in using force to advance its national interests is likely to be inhibited in the future."

Some believe Bolton is positioning himself to succeed his retiring mentor, North Carolina Sen. Jesse Helms, as the intellectual power behind their brand of diplomatic redneckery. Bolton's signature on the "unsigning" of the ICC treaty would be a huge asset in an election campaign. The North Carolina senator has praised his heir apparent lavishly. "[H]e is a man with the courage of his convictions. John says what he means and means what he says," Helms says. Still, Washington insiders believe his political prospects are hampered by an intellectual arrogance that won't sit well with GOP activists, whose presidential figurehead seems to draw a lot of his popularity from a real or feigned stupidity.

Shares