My mother threatened to kill herself so many times -- rifling through the kitchen drawers to find a knife, getting drunk and swallowing pills -- that when my brother called to tell me that she and my stepfather had been killed, I assumed it was a double suicide. Or that she killed him, and then killed herself.

My last words to her were "Fuck you." The day before she died was the first time my family had gotten together since my father died the year before. We met at my brother's house in Orlando, and although things started out OK, by the end of the evening Mama started up her usual shit, and I, tired of it all, said the magic words. My stepfather tried to get me to apologize, but I wouldn't. Mama called later and talked to my sister, and I remember holding the receiver to my ear, listening to her cry, saying she was sorry. I didn't say I was, though. After 21 years of dealing with her, I meant what I said.

She was 48 when she died. It was 1981. She and my stepfather were driving home from Clearwater Beach, drunk, still wearing their swimsuits at midnight, their bare feet grainy with sugary white sand. They ran their light-blue Plymouth under a tractor-trailer, shearing off the top. Both of them were thrown into the weeds on the side of the road. The next day the sheriff handed my brother a brown paper bag with a stiff bloody bikini in it. Instant death, he said, but I knew better. My mother had been aiming for that moment for a long time. She couldn't have chosen a better ending to her story.

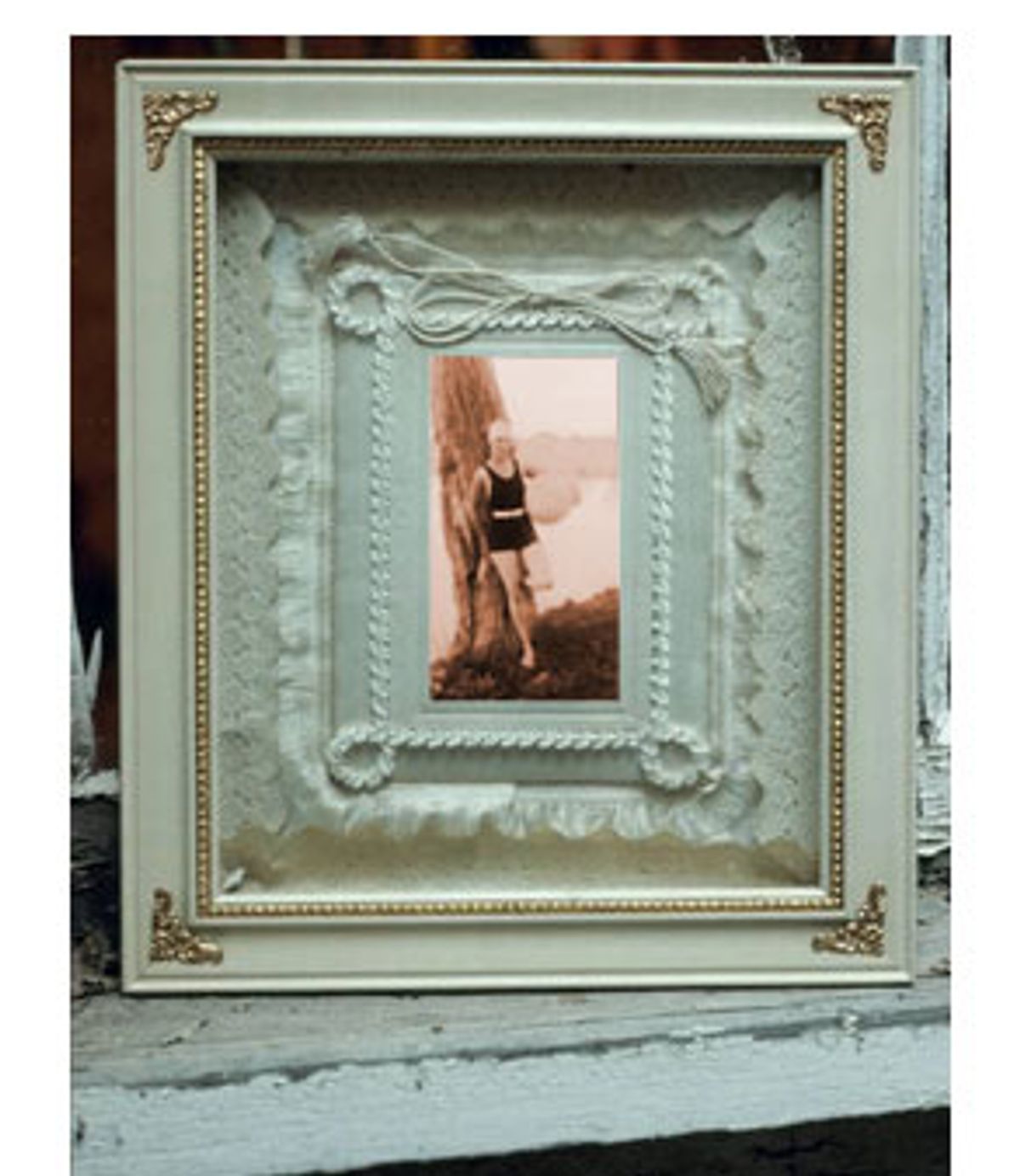

Her trajectory began inside the white scalloped edges of a photograph. She flirts with the camera, poses like a beauty queen standing in a small wooden boat on the shore of Lake Seminole, barefoot, hands on hips, head thrown back, a wide and bright smile. Open. She's wearing short shorts and she's conscious: "This is how I want to be remembered; I am as marvelous as Miss America." She gives herself to the camera, maybe to the eyes behind the camera.

I imagine my father before he was my father, smiling at my mother before she was my mother. He has a head full of glossy black hair. Squinting his eyes, bringing her into focus, he snaps this photo of her, thinks of butterflies resting on leaves, camouflaged, right before they are netted, pinned into boxes.

In the next photo, she and my father are leaning against an enormous pine tree near the banks of the Apalachicola River, right on the Georgia-Florida line. He's wearing shoes, thick brown brogans. She isn't. Her long slender feet are posed calendar-girl style. Daddy surrounds her with a bearlike grasp, his arm draped over her shoulder, his big hand pulling her to him. He smooches her ear with his mouth, whispering, "Baby, I love you, I love you so much." I can't remember my father's voice saying those words to my mother, but I know he did. Love her, that is, even if he did forget her birthday later.

Once, he did remember, and he hurt her feelings by buying her one pair of flimsy ladies underwear from the Dollar Store uptown and she wailed that nobody loved her, then threw the underwear in the garbage can beneath our pecan tree. But you can tell he loved her by looking at this photograph, the way his arm circles her, the way he holds her hand. She lets herself be contained, lets him whisper in her ear. This time the camera is peeping; Mama seems almost embarrassed at being watched; her eyes glance toward the ground.

Then there was a photograph taken after Mama had children. May 1962. That's three years after my sister was born. Four children in five years and all of a sudden she's wearing shoes, like she's afraid we're going to tramp on her feet. No more smiling, barefoot Miss America. The photograph is blurry, hazy. Mama's sitting in one of those old-fashioned shell-shaped lawn chairs, scrunched to one side as if she's going to share her seat with someone much smaller than herself. Her hands are clasped on top of her head, her legs crossed. She's smiling but it's a smile tinged with sorrow, the one I become most familiar with.

She sits beneath a tung oil tree, in front of a metal swing set. To her left is a clothesline, diapers fluttering in the breeze. In the corner of the photograph, there are bleary shapes, tiny feet, what seem to be hands. If you squint at this photograph you can almost see one baby helping another baby stand.

The stories I imagine behind those photographs seem as real to me as actual memories. What happened in real real life? The life I experienced? Consider me unreliable. I told my mother to fuck off, after all.

I am sitting in my mother's lap in my cousin Billy's backyard, a garden full of ferns, fountains, birds of paradise. Wind chimes dangle from the branch of a Japanese magnolia. Mama's chin is resting softly against the top of my head. The grass we sit on is so lush and green it's almost blue.

Even though I like sitting in my mother's lap, her chin pressed against the top of my head, my small body folded into hers, I want to get up and walk across that green grass and down the beaten path to the metal pens where my cousin's father, King, raised quail. I liked the smell of birdshit and cornmeal, the brownness of it all, the birds running back and forth in the powdery dirt, the worn wood, the earth beneath my feet.

When I think of that moment, I feel how torn I was between the quail and my mother. Her chin resting on my head was the completion of a circle, her body looped around mine. That circle said "You belong to me." I should've savored the moment, and I suppose I did or I wouldn't have remembered it, but the birds won, and I found myself edging through the azaleas to walk down the path bordered by weeds.

I looped my fingers into the wire pen, stared at the birds' speckled brown feathers as they darted back and forth. I hadn't learned yet to hold on to my mother's happiness while it lasted.

It never lasted long. One morning, completely flustered by trying to get my brothers and sister and I out the door and up the hill to school, she threw my satchel on the floor and started shouting, "I wish I'd never had any of you!" She ran into her bedroom, flung herself onto her bed and started crying uncontrollably.

I remember moving forward to touch her, feeling sick on my stomach, on the verge of tears myself. I don't remember what happened later that day -- my father probably came home, set things right. I can't remember leaving the side of her bed. In that memory I stand there, never moving, watching my mother sob into her hands, my heart forever breaking.

My mother was a study in opposites: a classic manic-depressive, full of light and dark. When she wasn't suffering from one of her depressions, she took me and my brothers and sister to the Gulf of Mexico where she wore a bikini and we had picnics and built sand castles and played Goofy Golf.

Back home, she took us out to the country to fly kites. She let us drive down red dirt roads before we were old enough, and took us fishing practically every day during the summer. She once saved a boy from drowning even though she couldn't swim herself, and she managed to laugh about the rattlesnake who'd crawled up under the quilt she sat on while she fished at Lake Seminole.

She would go into the bait store to buy crickets or worms, but she wouldn't answer the door at our house. Once when a favorite teacher of mine came to visit, my mother locked herself in the bedroom and wouldn't come out. Her inability to face people led to my having to go into the drugstore to get refills of the drugs she was addicted to, after my brothers refused to. I died of embarrassment every time.

Gradually, she began drinking, too, and once drunk, she'd climb out of the windows and sit hunched over in the dirt beneath the azaleas, not even speaking to us when we begged her to come back into the house.

When she and father weren't home, my sister and I snuck into their bedroom to snoop around. It was silent and still as a church, full of mysteries. My sister and I always dug in the cedar chest to look at the blue jumper Mama'd worn as a baby. In the beginning there were quilts and old pocketbooks, and a blue-and-green silk dress I never saw her wear, couldn't even imagine her wearing. There was a Nazi flag my father said he took from some dead Germans at the end of World War II.

Later, there were surprises, the things my parents hid, revealing they'd changed. We found a dirty-joke book in the closet; another time we found a manual on how to have sex. And then one afternoon, probably the last afternoon we snooped, there was a note in an envelope, a scrawl of words that said "Your wife is having an affair."

I was stung by the sentence, but it wasn't exactly a revelation. I figured she was running around with this black-haired cowboy she worked with. Something was going on. What was confusing was who put the note in the cedar chest. Who would even want to save a scrap like that?

Mama finally left my father and the black-haired cowboy or whoever he was, and moved to Tampa to live with another man. She came to visit me once during this period. She sat in my one-room apartment beneath a poster of flying dykes from the Michigan Womyn's Music Festival, uncomfortable, as if she were visiting a stranger. I sat across the room from her, staring at the shadows the yellow lamplight made on her face.

It wasn't until after she died that I found the note she stuck inside my dictionary that night. "Help me; I need your help," she'd scrawled on a piece of drawing paper. It was strange, finding those words stuck in my dictionary months after she died. It was as if she'd known I'd snooped all those years; as if she were saying, "Here, find this." I kept it, even though it reminded me of how sad she'd been and how little I'd been able to do about it.

After her death, my sister went down south to clean out my stepfather and mother's trailer. As she moved boxes outside, the woman next door came over and shouted at her: "They were nothing but a couple of drunks." In the end, I suppose that's how she appeared. Maybe that's what drove me to tell her to get fucked the day before she died. But that's not how she appears to me now. Maybe it's because I wish I could rewrite my last words to her, have the story end a different way.

Yes, she scared the hell out of me when I was a child. She hurt me. She stole corn from a field in the country, filled the trunk to the brim while I cried, worried she'd get shot. But she also took me to a Jackson County farm to pick hampers of White Acre peas she paid for. She taught me to appreciate the tinny sound of AM country-music radio. She let me drive to Panama City Beach when I was 12 years old. She bought me drawing paper when she thought I wanted to be an artist. She taught me how to bait a hook and how to hold a bream in my hand without getting finned.

I think of her at the oddest moments -- when my girlfriend and I travel to Central Florida on back roads and pass one of those rinky-dink horse-riding corrals. I stopped at one of those once with my mother, and still remember the way she looked in the dappled green shadows beneath the trees. I think of her when I go to the Gulf of Mexico or see a stringer full of silver fish, a varnished bamboo fishing pole, paper kites, a car driving down a road with a roostertail of red Georgia dirt blowing up behind it.

I can't remember my mother's voice anymore, how she sounded when she said, "I wish I'd never had you," but I remember how she looked in her white cotton nightgown, leaning over me at night, nibbling words into my ears, Mmmmmmm, I love you. Her breasts brushed against the sheets as she bowed her body over my bed. I remember her smell, the sweet, cherry-almond scent of Jergens Lotion. I can't remember the exact brown of her eyes or how long her eyelashes were or how her lips were shaped, but I can remember how her chin rested on the top of my head, making us a perfect circle, just for a moment.

Shares