There are few exercises as forlorn and masturbatory as liberals whining that "if Clinton did what Bush has done"... fill in the blanks. It's OK; we all do it, in the privacy of our own homes. But that kind of indulgent self-pity normally shouldn't seep out into public discourse. Cry into your beer, friend. Suck it up.

But the news that President Bush was warned of an al-Qaida hijacking plot before Sept. 11, after eight months of his boosters blaming the tragedy on Clinton, makes it hard not to smart at the double standard that the right wing, and much of the media, has used to judge this president and his predecessor.

The administration's handling of the August threat is personal to me. I flew from San Francisco to Boston Aug. 6, the very day Bush, on a monthlong vacation at his Texas ranch, got "generalized warnings" about an al-Qaida hijacking plot. Barely five weeks later, three planes either leaving from or headed to those two cities exploded into buildings, killing everyone on board and thousands on the ground.

I actually flew cross-country three times that month, but of course, I wouldn't have flown even once had I known what Bush did. And I'm the reason, according to National Security Advisor Condoleezza Rice, that the president couldn't reveal "all of the chatter," as she put it, about al-Qaida hijacking threats pre-Sept. 11.

"You would have risked shutting down the American civil aviation system with such generalized information," a nervous, harried Rice told reporters Thursday. "You would have to think five, six, seven times about that, very, very hard."

Indeed. I certainly hope Bush thought "five, six, seven times" about what he learned Aug. 6. I hope he thought "very, very hard."

In the days after Sept. 11, liberal critics of the president stepped lightly, striving quite rightly to place patriotism before partisanship. Even after these latest 9/11 revelations, it's important for Bush opponents to put the good of the country ahead of political posturing. We need answers that only an impartial investigation can unearth.

Yet posturing is exactly what we've been getting from the White House and its conservative defenders since CBS News broke the 9/11 warning story on Wednesday. Certainly, we shouldn't jump to conclusions, or simplistically insist the recent news means Bush could have prevented those 3,000 deaths on Sept. 11. But it's the White House, not its critics, that is trying hardest to spin the latest revelations, rather than explain them -- while, at the same time, blaming Democrats for playing politics. It's dizzying, but it isn't working so far.

Clearly the president's defenders want to minimize the seriousness of the August warning Bush received. Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld told his friend Rush Limbaugh Thursday that "through the spring and summer there was a great deal of threat reporting indicating a variety of different things all over the world, but without any specificity as to what might happen."

What is Rummy saying here: That al-Qaida didn't send dates, times and photos? In fact, evidence is mounting that the government had plenty of specificity about al-Qaida threats from the FBI alerts in Phoenix and Minneapolis, to the alarms sounded in Europe before the G8 Summit in Genoa, Italy, to Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak's dire warnings about an impending al-Qaida strike last summer. On Friday, yet another story broke that thoroughly undermined the Bush team spin that no one could have imagined an airplane-as-missile attack on a building. AP reported that in 1999, a federal intelligence study warned specifically that al-Qaida might crash explosives-filled airplanes into the Pentagon.

Maybe most chilling, we learned Friday from the Washington Post that the government's top counterterrorism official, Richard C. Clarke, gathered high-level leaders of the Federal Aviation Administration, Coast Guard, FBI, Secret Service and Immigration and Naturalization Service at a meeting July 5 and told them flatly: "Something really spectacular is going to happen here, and it's going to happen soon." All counterterrorism agencies were told to cancel vacations and nonessential travel. "For six weeks last summer, at home and overseas, the U.S. government was at its highest possible state of readiness -- and anxiety -- against imminent terrorist attack," the Post revealed. But the American public was told nothing, and it's still not clear if Clarke's dire warning was shared with the president. By the time Bush received his CIA briefing on Aug. 6, the government had begun to stand down from the alert.

How much did Bush know and when did he know it? This is obviously what Congress needs to get to the bottom of. But the Bush administration has been resisting inquiry into that very question for eight months. The president himself went to Senate Majority Leader Tom Daschle at the end of January and asked him to limit Congress' probe, insisting it would divert needed resources from the war on terror -- a rather suspicious request in light of the latest news. On Thursday, faced with bipartisan calls for an investigation, the administration resorted to its favorite tactic: intimidating the opposition by questioning its patriotism. An angry Vice President Dick Cheney, who's opposed congressional investigations into Sept. 11 all along, suggested that asking how much Bush knew in advance of the terror attacks was "incendiary," adding, "Such commentary is thoroughly irresponsible and totally unworthy of national leaders in time of war."

That's a breathtakingly arrogant statement, even from our imperial vice president. Cheney has spent too long in his bunker: This is America, and authoritarian bullying can't overpower democracy, even during wartime. Or unlimited anti-terror time, or however this period of ill-defined conflict might be described.

The Bush high command protests too much. They seem to be running scared. But let's take their objections at face value.

Let's assume the CIA's Aug. 6 warning to Bush wasn't terribly specific. The New York Times reported Thursday that the CIA briefing "was based on 1998 intelligence data drawn from a single British source." It would be enlightening to know exactly what that intelligence data was, and whether congressional leaders were given the same information. But let's assume it was a vague warning, one of many we know the president received last summer.

Let's also accept Rice's argument: Making public "all of the chatter" about al-Qaida hijacking threats would have disrupted the nation's airlines, and to some extent, the economy. It's certainly true that without the horror of the World Trade Center and Pentagon attacks, such a warning would have been a tough sell for the administration. The dislocation to the economy -- particularly to the travel industry during that peak vacation season -- would have provoked skepticism and no doubt criticism about whether the alert was justified. Definitely a political risk there.

And what if the president had imposed tighter airport security, including tougher scrutiny of Middle Eastern or Muslim men flying in the U.S.? Surely we'd have seen a spate of stories, maybe even in Salon, about racial profiling and the threat to civil liberties such moves represented, as well as push-back from Democrats in Congress.

But I have to say, So what? This administration braves criticism of its civil liberties policies and its handling of the economy every day. And the nation would have survived the temporary dislocation, just as it did after 9/11. The question is how much the Bush administration would have suffered politically if the nation didn't know it had to endure such hardships, or else suffer what we did Sept. 11. But risk is crucial to political leadership. Rice's demurrer is a coward's way out.

When the nation's top counterterrorism expert warns the heads of U.S. security agencies that "something really spectacular is going to happen here, and it's going to happen soon," I think Americans should be notified. If Clarke is a hothead prone to fanciful exaggeration, he should be relieved of his duties. If not, his warnings should be heeded and publicized.

We don't know if Bush was told of Clarke's dire warning. We don't know if he was briefed on the disturbing FBI alerts about Middle Eastern men in U.S. flight schools, or Zacarias Moussaoui's capacity, in one FBI agent's words, to "fly something into the World Trade Center." Condi Rice said Thursday she'd get back to us on that. We're still waiting for her answer.

Even if it turns out the White House wasn't informed about the FBI alerts, Bush is not off the hook. Enron executives used the same excuse -- we didn't know -- when confronted with their company's flagrant missteps. But of course executives are supposed to know. And if they don't, it's a poor reflection on their management skills. Blaming FBI officials smells strongly of passing the buck. As we all know, the buck stops in the Oval Office. That old liberal refrain -- "imagine if this were Clinton" -- rings true here. The Republicans and the press would never have let Bush's predecessor get away with blaming the G-men.

Meanwhile, Bush's defenders in the media are insisting this is a nonstory. I waited all day Thursday for Andrew Sullivan, one of the president's smartest boosters, to deal with the mess on his Web site, in vain. He talked about college anti-Semitism, a LEGO version of the crucifixion and the collapse of the Euro-left. It wasn't until around 2 a.m. Friday morning -- is that bar time in D.C.? -- that he weighed in.

"Several of you have written me asking why I haven't jumped on the story that President Bush was told of threats of al Qaeda hijackings before September 11. The reason is simple: it's not a story. So far as I can tell, there were no specific threats, no suggestion of commandeering planes to use as missiles, nothing that could be differentiated from any number of such warnings before or since."

This is absurd, and Sullivan would be the first to tear holes in this limp rebuttal if a Democratic president were in the hot seat. There were a growing number of specific terrorism alerts in circulation at the time. And if the Bush administration had decided before 9/11 that terrorism was a top security priority, the president would certainly have acted more decisively after his Aug. 6 briefing. But as the Washington Post reported on Friday, "Bush and his Cabinet advisers were not yet disposed to respond to al Qaida as a first-tier national security threat ... As late as Sept. 9, Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld threatened a presidential veto when the Senate proposed to divert $600 million to counterterrorism from ballistic missile defense."

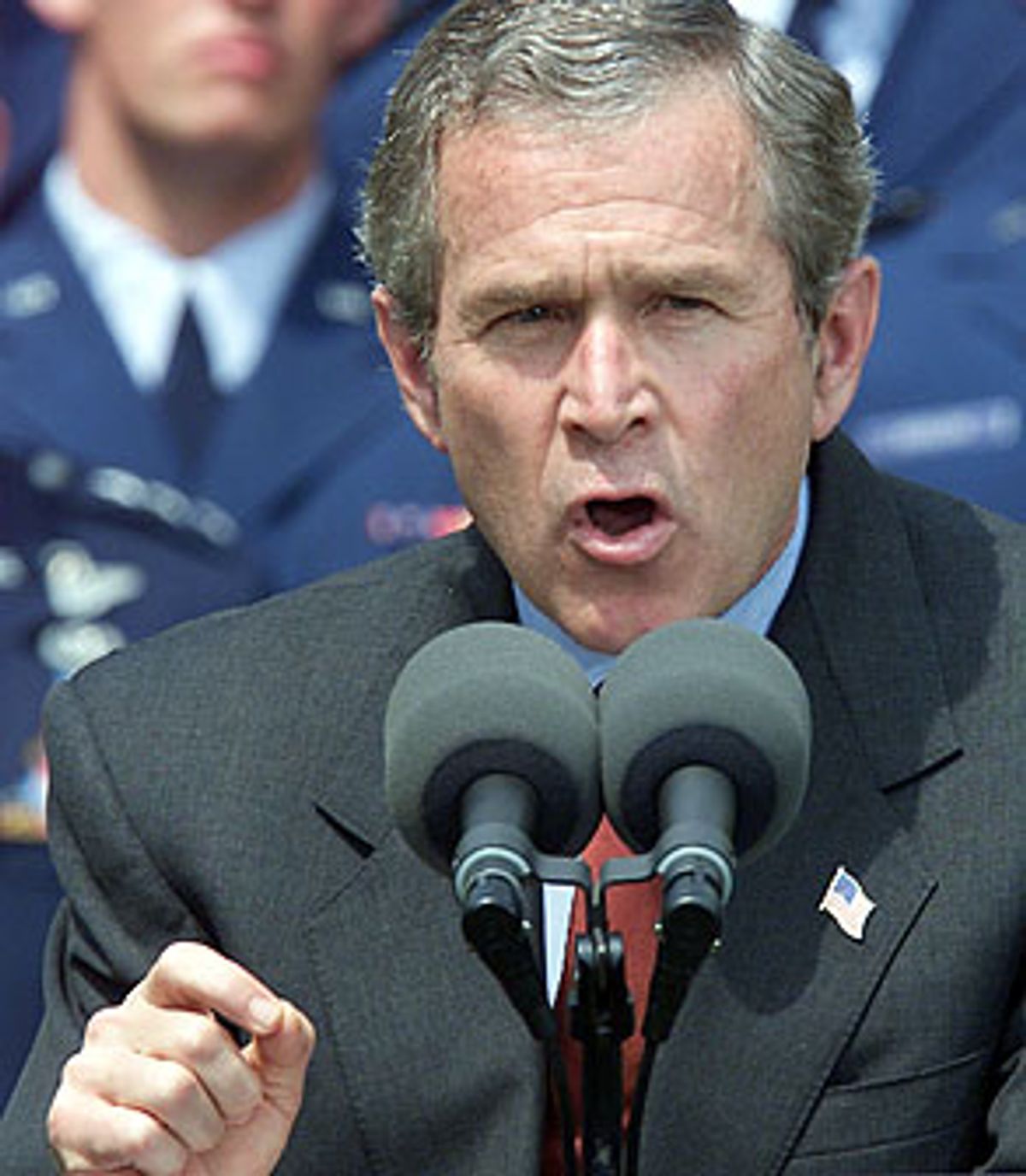

After letting Rice and other aides take the heat on Thursday, Bush himself finally talked about the growing scandal on Friday morning, at a Rose Garden ceremony to honor Air Force cadets and their football team -- his favorite sort of photo op because it doesn't allow for press intrusion. "Had I known the enemy was going to use airplanes to kill on that fateful morning, I would have done everything in my power to protect the American people," he declared, adding, "I take my job as commander in chief very seriously" -- a strange reassurance that should go without saying, but in this case, unfortunately, doesn't.

Bush's hiding behind his minions Thursday raised bad memories of Sept. 11, when he spent the day hopping around the country from one high-security location to the next while his advisors claimed (falsely) he was being protected from threats against him. This time, he needs to stand before the public and answer the dozens of tough questions that are being raised about his administration's state of awareness before 9/11. The White House needs to drop the script and put the president in front of the press corps. And it needs to cooperate with congressional leaders who have called for full and independent inquiries. Such investigations would not, as Ari Fleischer suggested this week, be a waste of taxpayers' money. In fact, this is a primary reason we pay the government our taxes -- to protect us, and when it does not, to find out why.

Shares