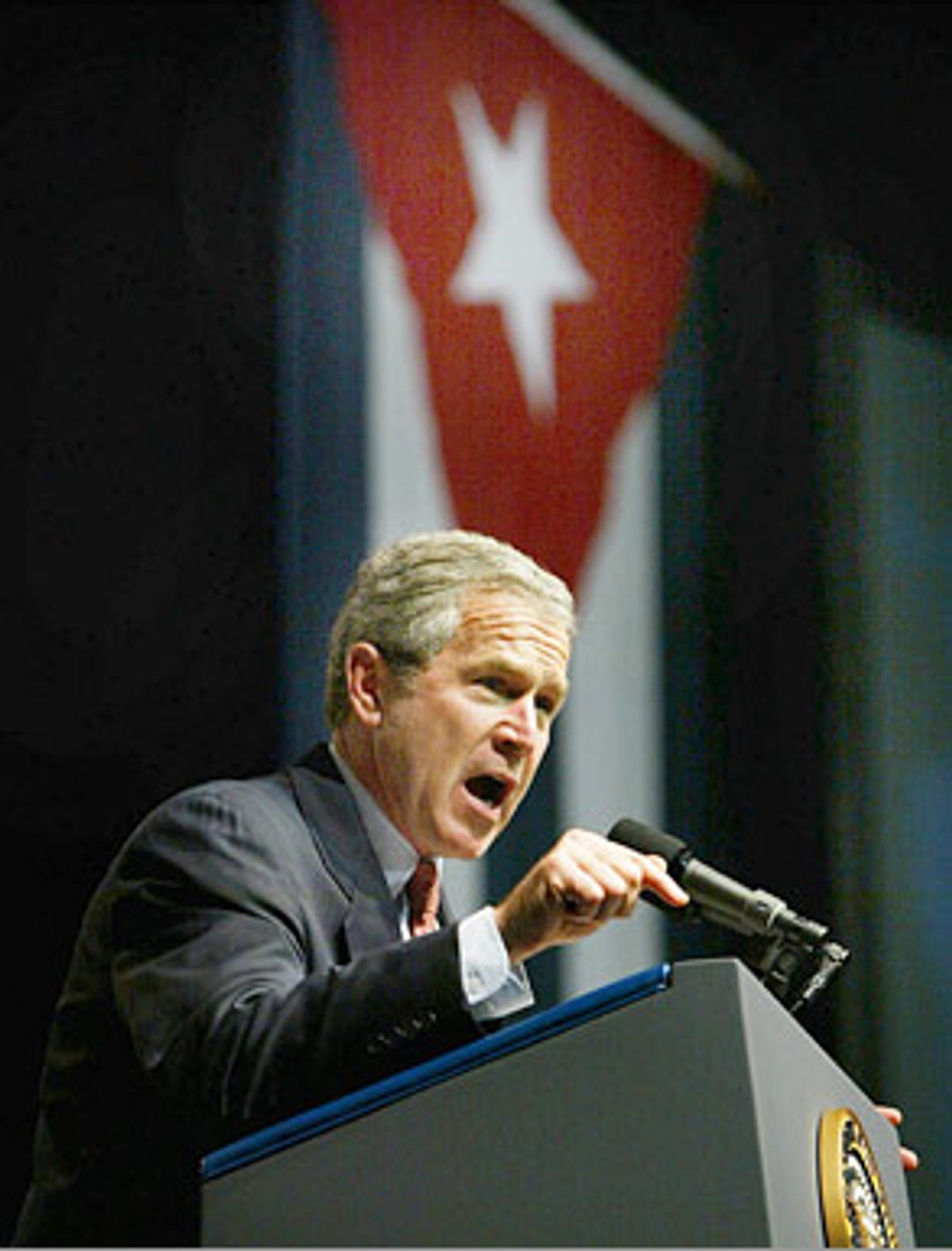

During President Bush's Monday address in Miami, in which he offered modest policy alterations toward Cuba, his language was brimming with denunciations of Fidel Castro -- including references to the Cuban leader as a "relic of the past" and a "tyrant" -- tailor-made for an audience of fiercely anti-Castro exiles.

Bush has good reason to tell them what they want to hear: Cuban American voters were crucial in the razor-thin 2000 presidential balloting in Florida. Stung by the actions of the Clinton administration in the Elián González affair in 2000, more than 80 percent of Cuban Americans in Florida voted for Bush, according to exit polls, compared with the 62 percent of Cuban Americans who voted for Bob Dole in 1996. The swing represents tens of thousands of votes, bolstering the claim of some Cuban Americans that they won the presidency for Bush.

Monday's event appealed directly to these voters. Gov. Jeb Bush, running for reelection in November, introduced his brother, the president, at the event, which had many of the trappings of a campaign rally, including a speech by Jeb in Spanish. The president later attended a $25,000 per couple fundraiser for the Republican Party at the home of Cuban American real estate developer Armando Codina, Jeb Bush's former business partner. Ironically, President Bush's Miami pep rally and his undying commitment to continuing a hard-line policy toward Cuba took place when support for such a policy is declining, not only with former President Jimmy Carter, who visited Havana last week, or the bipartisan Cuban Working Group, which consists of 40 members of Congress who last week called for easing sanctions, but with an emerging majority of Cuban Americans, as well.

A recent poll, for instance, showed a statistical dead heat among Cuban Americans on the issue of unrestricted travel to Cuba, even though the poll, commissioned by the Cuba Study Group, a loose association of a dozen wealthy Cuban Americans, probably skewed slightly conservative by excluding the responses of those Cuban Americans who said they were not interested in Cuba issues. (When asked why they weren't interested, the most frequent answer was that they did not agree with exile politics.) And a poll conducted by Florida International University in 2000, which included Cuban Americans and a national sample of U.S. residents, showed 53 percent of Cuban Americans in Miami and 63 percent of all Americans nationwide supported unrestricted travel to Cuba. Support for the unrestricted trade of medicine and food was also substantially higher for both groups.

Evidence in the Cuban American community of a trend toward increased relations with Cuba also exists outside of polls. Last March, a group of prominent Cuban Americans hosted an anti-embargo conference at the posh Biltmore Hotel in Coral Gables that was attended by more than 300 people. Such a gathering would have been unthinkable in the climate of intimidation present in Miami just a few years ago. This time, Reps. William Delahunt, D-Mass., and Jeff Flake, R-Ariz., leaders in the 40-member congressional Cuba Working Group, addressed the crowd, while outside two dozen peaceful demonstrators failed to cause any disruption. The event, titled "The Time Is Now" (to revise Cuba policy), did prompt Reps. Ileana Ros-Lehtinen and Lincoln Diaz-Balart, hard-line Cuban American GOP Congress members from Miami, to call a press conference at an adjoining facility to denounce the event.

But even the Cuban American National Foundation (CANF), historically the most powerful hard-line group, is moderating its rhetoric while holding onto its support for the embargo. The Cuban Liberty Council, a group of ultra-hard-liners who broke with CANF over the new approach, continues to espouse hard-line policies and spew shrill rhetoric. But the group represents a declining sector of older exiles, and no longer the majority.

The trend toward moderation poses the question of why the Bush administration sticks to a failed and increasingly unpopular Cuba policy. The modest policy proposals Bush outlined include ending restrictions on humanitarian assistance by U.S. NGOs to Cuban civil society groups, working to restore direct mail service between the two countries, offering scholarships to the children of Cuban dissidents and modernizing Radio and TV Marti. There is not very much new in these policies, and few observers give them much chance of producing major changes in Cuba, where they are sure to be rejected.

But a good number of Cuban Americans still support the embargo, mostly those who've been here the longest and are vastly more entrenched politically and economically than more recent arrivals. They are more likely to be naturalized and registered to vote, with a much greater capacity to make political contributions. They may no longer be the majority of exiles, but they are the most important political demographic. As such, they pretend to speak for the community as a whole.

So in the immediate future, Bush's veto power, along with the capacity of the GOP leadership of the House of Representatives to thwart the will of the majority of members through legislative maneuvers, equals little or no change in the status quo. But the increasing numbers of opponents to the embargo, even among Cuban Americans, won't be able to be ignored much longer.

Shares