From the Senate floor, Sen. James Inhofe, R-Okla., preached what was essentially a sermon about Israel last December. "The Bible says that Abram [Abraham] removed his tent, and came and dwelt in the plain of Mamre, which is in Hebron, and built there an altar before the Lord," he said. "Hebron is in the West Bank. It is at this place where God appeared to Abram and said, 'I am giving you this land' ... This is not a political battle at all. It is a contest over whether or not the word of God is true."

As Inhofe's speech suggested, for elements of the Christian right, pro-Israel fervor has ascended to the realm of the sacred. Christian leaders Ralph Reed and Gary Bauer both say that their support of Israel -- and Israeli expansionism -- is partly rooted in biblical injunction. Bauer says, "There are a variety of Old Testament scriptures in which God is saying to Abraham that the people of Israel will occupy all the land between the sea and the river," which he says means the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan River. "There's a belief that this is covenant land," he adds.

Such views have concrete consequences -- as Nicholas Kristof wrote in the New York Times, evangelical internationalism is a "broad new trend that is beginning to reshape American foreign policy." Many Jewish leaders have welcomed evangelical support on Israel. Yet despite feel-good talk of ecumenical alliances, conservative Christians aren't just acting as backup for their Jewish brothers and sisters. They have an agenda of their own. For now, it coincides with mainstream Jewish concerns. It won't always.

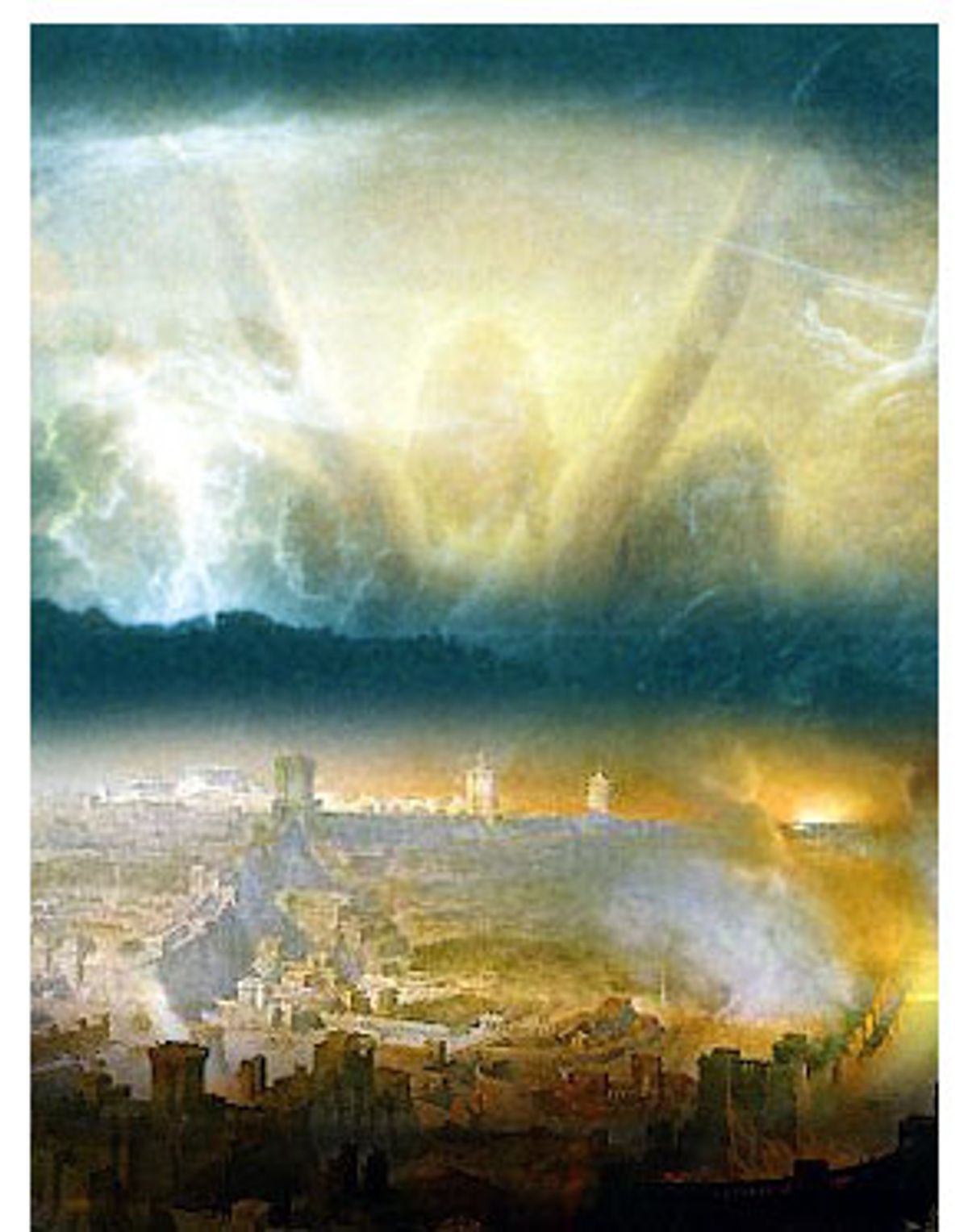

Put baldly, millions of evangelical Christians see forewarnings of Armageddon in the crisis in the Middle East. Followers of dispensationalism, a major strain within American evangelical Christianity, they believe that the return of Jews to Israel and the restoration of Jewish sovereignty over the Temple Mount is a precondition for the rapture, the apocalypse and the return of Christ.

"I believe that Jesus can only return when all of the Jews have returned to their land," writes Norbert Lieth, author of 18 Christian books, in the dispensationalist magazine "Midnight Call." Television preachers like Jack Van Impe and John Hagee and bestselling Christian writers like Hal Lindsey explain the current struggle over Jerusalem, Gaza and the West Bank as prophesy made manifest. They see their interpretation of Daniel and the Book of Revelations played out every day on the news.

For them, there can be no negotiation over what they call "Judea and Samaria" despite the fact that many Israelis, and Jews worldwide, hope Israel eventually pulls out of the territories. Randall Price, jet-setting founder of World of the Bible Ministries, says, "In the book of Genesis, there are territorial dimensions for the land that is given to Abraham and his descendents. It's from the river of Egypt to the river of the Euphrates." In his view, Israel's right to that land, which extends into modern-day Iraq, is absolute. As for the Palestinians, Price says, "Ishmael has said that his descendants would live to the East of their brother. There's a much larger geographical territory allotted to them."

The Palestinians, he says, have "no historic claims" to the land they're on now and should move to an Arab country outside Israel's dominion.

Seen in this light, Dick Armey's comments to an incredulous Chris Matthews on MSNBC's "Hardball" a few weeks ago make more sense. "I am not content to give up any part of Israel for that purpose of that Palestinian state," he said. "I happened to believe that the Palestinians should leave." After all, Armey might have added, the Bible says so.

While Armey has made his evangelical Christianity clear, there is no evidence that he believes in dispensationalism. According to his communications director, Armey's Zionist stance stems from solidarity with Israel in the war against terrorism. Similarly, a spokesman for Inhofe insists that dispensationalism "has not really figured into his support for Israel."

Reed and Bauer also distance themselves from dispensationalism. "My support for Israel has little or nothing to do with theology of the end times," says Reed. "Evangelicals have a fairly expansive view of God's sovereignty. I believe that he'll be able to work out Israel's role in the end times without our help."

Bauer concurs, "I've always been uncomfortable trying to discern prophetic literature. Christ himself says no man knows the hour or the day, so in my own faith life I've stuck pretty much to the basics of my belief in Jesus Christ as the son of God and have left it to others to argue out what at times are fairly esoteric differences."

There is no reason to doubt either man's sincerity. At the same time, it is crucial to note that while both minimize the influence of dispensationalism, neither will explicitly disavow it. Meanwhile, at least one Republican leader seems to believe the rapture is imminent -- a plaque in Tom DeLay's office reads, "This could be the day."

That's one reason that Chip Berlet, an analyst with the progressive think tank Political Research Associates, argues, "The current administration in the United States is packed with people who are literal Bible believers and who see in Israel a specific role in the end times." The most visible believers, says Berlet, are Attorney General John Ashcroft, Armey and Delay. "My argument is that you don't have to say, 'I am a dispensationalist' to be a person influenced by these apocalyptic metaphors. The more you're embedded in a Christian fundamentalist culture, the more you're going to be influenced by these ideas even if you claim you aren't."

Gershom Gorenberg, Israeli journalist and author of "The End of Days: Fundamentalism and the Struggle for the Temple Mount," cautions that we need to pay attention to these views. "There's a tendency which is very common among secular-leaning people not to take theology very seriously," he says. Yet evangelical leaders are hardly reticent about the central role that religion plays in everything they do. Gorenberg adds, "When Jerry Falwell says, 'I don't think there's a West Bank, there's Judea and Samaria,' why shouldn't I take seriously that he's deriving that from the bible?" As Gorenberg points out, important elements in Israeli society take these people very seriously indeed. When Binyamin Netanyahu visited Washington during the '90s, he met with Jerry Falwell and other Christian leaders before he met with Bill Clinton. American evangelicals have raised millions to return diaspora Jews to Israel. Fundamentalist groups like the Christian Friends of Israeli Communities fund settler movements, "those pioneers now fulfilling the covenant to Abraham, Isaac and Jacob regarding the restoration of all the land God has allocated to Israel," as one pamphlet said.

Yet despite its international influence, most people on America's godless coasts have never heard of dispensationalism. It's one of those words that reveals the yawning ideological gulf between red states and blue. To secular urbanites, it might seem like just another example of fringe American madness, something akin to UFO cults. But it's thoroughly mainstream -- far more so than agnosticism. Darrell Bock, research professor of New Testament studies at the Dallas Theological Seminary, says that the most prevalent view among evangelicals is an unequivocal support for Israel, and that dispensationalism plays a large role in their conviction. And Gorenberg says, "Dispensationalism is a predominant belief among fundamentalists."

It matters that a lot of evangelicals are dispensationalists because a lot of Americans are evangelicals. According to a Gallup Poll taken in March, "46 percent of Americans describe themselves as 'born-again' or evangelical." In a 1999 Newsweek Poll, 71 percent of evangelicals said they believed that the world would end in a battle at Armageddon (which is itself a corruption of the name of the Israeli town Megiddo) between Jesus and the antichrist.

Of course, not every Christian who believes Jews have a God-given right to Palestinian territory is an end-time fundamentalist. "I'm not going to deny that it's a factor, of course it's a factor, but it's an insignificant factor," says Reed. "I think it shows a misunderstanding of both the complexity and the character of Christian support for Israel and the Jewish people."

As Bauer says, Christian support for Israel can be explained partly by the fact that evangelicals typically take a hard line on foreign policy. "American Christians were generally supportive of a more hawkish view in the cold war. It was seen in moral terms. Reagan would refer to us as a shining city on the hill, and many Christians did see it that way. I think now there is a strong sense among American Christians that there is a clash of civilizations going on, and broadly speaking, Israel and the United States are defending Western civilization."

Israel aside, evangelicals tend to be hostile toward Islam, as demonstrated by Billy Graham's son Franklin's statement that it is "a very evil and wicked religion."

"It's certainly seen as an illegitimate faith," says Bock. "Judaism supplies the roots for Christianity and Jesus was Jewish, so there is a recognition of kinship that doesn't exist with Islam. There is also a history of Islam's violent treatment of Christians and Jews that has accelerated this reaction that you've seen. Certainly something like 9/11 takes it high on the charts -- if that can be done as an act of religious faith, this is not a religion worth respecting." Evangelicals point out the horrors perpetrated by Sudan's Muslim government against the country's Christians -- including the widespread slave trade -- as evidence of the religion's amorality.

Yet if end-times prophesy can't completely account for the Christian right's embrace of Israel, it also can't be disentangled from it. As Gorenberg says, "There's a package deal going on here. The same people who hold this particular Christian theology are also conservatives in other ways. They tend to see the world as divided between good guys and bad guys and they tend to see force as the proper solution." They may speak in geopolitical terms, he says, "but they're influenced by a mythological view of the state of Israel."

Besides, even Republicans of the Christian right who don't believe we're on the cusp of the second coming have to appease the evangelicals in their constituency, and among those evangelicals, dispensationalism is as much a part of the culture as is "Star Wars."

Perhaps the most overwhelming evidence for the prevalence of dispensationalism is the success of the "Left Behind" novels. Co-written by Tim LaHaye, former leader of the Moral Majority, and Jerry B. Jenkins, the books are end-time thrillers that have sold more than 50 million copies. As Brodrick Shepherd, owner of the prophecy clearinghouse Armageddon Books, says, the books "have had a tremendous amount of influence in bringing awareness to the idea of dispensationalism."

There are currently 10 books in the series, which tell the story of those left behind after the rapture to deal with the tribulations. The books begin with a ferocious military assault on Israel. A group of Christians, shamed by the weakness of faith that caused them to miss the rapture, band together to fight the antichrist and, among other things, protect the righteous Jews who urge their brethren to turn to Jesus. Meanwhile, a deluded Jewish Nobel prize-winner colludes with the antichrist, one of whose first acts is to forge a cynical peace with Israel. Another popular dispensationalist novel, Hal Lindsey's 1996 "Blood Moon," features an Israeli prime minister who heroically launches preemptive nuclear strikes against the major cities of the Arab world.

It's not just fiction spreading the word about Israel and the last days. "Jack Van Impe Presents," which bills itself as "a weekly news program which analyzes and evaluates world events in the light of Biblical prophecy," is broadcast in all 50 states and throughout the world. So is a program by Pastor John Hagee, who has written that Jesus will only return after the "most devastating war Israel has ever known." End-times teachings are popular on "The 700 Club" and on many of the 1,300 Christian radio stations that are part of the National Religious Broadcasters association. There are Dispensationalist magazines like Endtimes, Midnight Call and Israel My Glory. According to Shepherd, who is fascinated by end-time prophecy but critical of dispensationalism, "When you walk into a Christian bookstore, everything you find on prophecy is going to be from a dispensationalist viewpoint."

For some Jews, the prevalence of dispensationalists has been a boon both politically and economically. Orthodox Rabbi Yechiel Eckstein, author of "Understanding Evangelicals: A Guide for the Jewish Community" and head of the International Fellowship of Christians and Jews, distributed $14 million last year that he raised almost exclusively from American evangelicals. Most of the money went to resettle diaspora Jews in Israel and to help care for new arrivals. He has an office in Chicago staffed by 50 people, most of them evangelical Christians, and one in Jerusalem staffed by Jews. There are 3,500 churches involved with his organization. Recently, he said, the Israeli prime minister's office asked him to start doing public relations work for Israel in the Christian community worldwide.

"The Jewish community over the years has struggled with the question of whether these people are our greatest friends and allies or our greatest adversaries," he says. "I obviously wouldn't be in this business unless I felt that they were among our greatest friends."

Abraham Foxman, executive director of the Anti-Defamation League, doesn't go that far, but he's also not terribly concerned about the evangelicals' motivation. "Some [evangelicals] are motivated theologically, in that for the Second Coming of the Messiah, one of the prerequisites is for Jews to be safe and secure in the Holy Land," he says. "That's not a reason for us to reject them. I believe that when the Jews are safe and secure in the Holy Land the Messiah will come for the first time. So what?"

After all, as Foxman indicates, Christians certainly aren't the only ones with a messianic view of Israel. While secular or reform Jews -- that is, most Jews -- tend to see the need for a secure Jewish homeland as a political matter and are thus willing to negotiate its borders, Orthodox Jews share the evangelicals' conviction that Israel is covenant land. That's why when it comes to issues like settlements, Rabbi Eckstein says, deeply religious Jews have more in common with Christians than with the Jewish mainstream. Israel, says Eckstein, "is the Holy Land for both the religious Jew and for the evangelical Christian. It is a miracle, the ingathering of the exiles. It is God's redemption."

But the two versions of redemption are starkly different. In the evangelical one, the Middle East is convulsed by unprecedented violence and most Jews die.

The vast majority of Jews desperately want to avoid a full-scale conflagration between Israel and the Arab world. Dispensationalists don't. In the dispensationalist narrative, Christians will be raptured to heaven before all the fighting between Jews and Muslims starts. Everyone left will face mass death and destruction. "Some people see some of the imagery in Revelations being caused by nuclear weapons," says Brodrick. Thus evangelical Christians' support for policies like the permanent takeover the West Bank and Gaza and even, in some cases, the expulsion of Palestinians into Jordan, should be understood in the context of a worldview in which world war is inevitable.

Eckstein recalls an ad for a prophesy book in Charisma magazine that said the post-rapture tribulations would "make the Holocaust seem like a party." Though he believes most evangelicals are more "humble and responsible" than that author, he says, "There are those who are so definitive and absolute about the future, and their theology does entail the destruction of millions of Jews in the battle of Armageddon. I believe it says in the Book of Revelations that the blood will be so high that it will reach the bridle of a horse."

Dispensationalist Christians believe that this is all in the service of establishing the reign of Christ on earth. Yet while they chase this fantasy, they're content to put real lives -- Jewish lives -- on the line. "It doesn't make me feel any better when they tell me to keep the whole West Bank when I don't think that's for the benefit of Israel politically," says Gorenberg. "When somebody's hope for where Israeli policy will lead is Armageddon, clearly they're going to be judging things differently."

For now, as Jews and evangelicals work together, those differences might not matter. Yet as American government support of the mujahedin shows, realpolitik partnerships against metaphysical evil can turn rancid. When people believe their politics are endorsed by God, today's ally can be tomorrow's Satan.

Shares