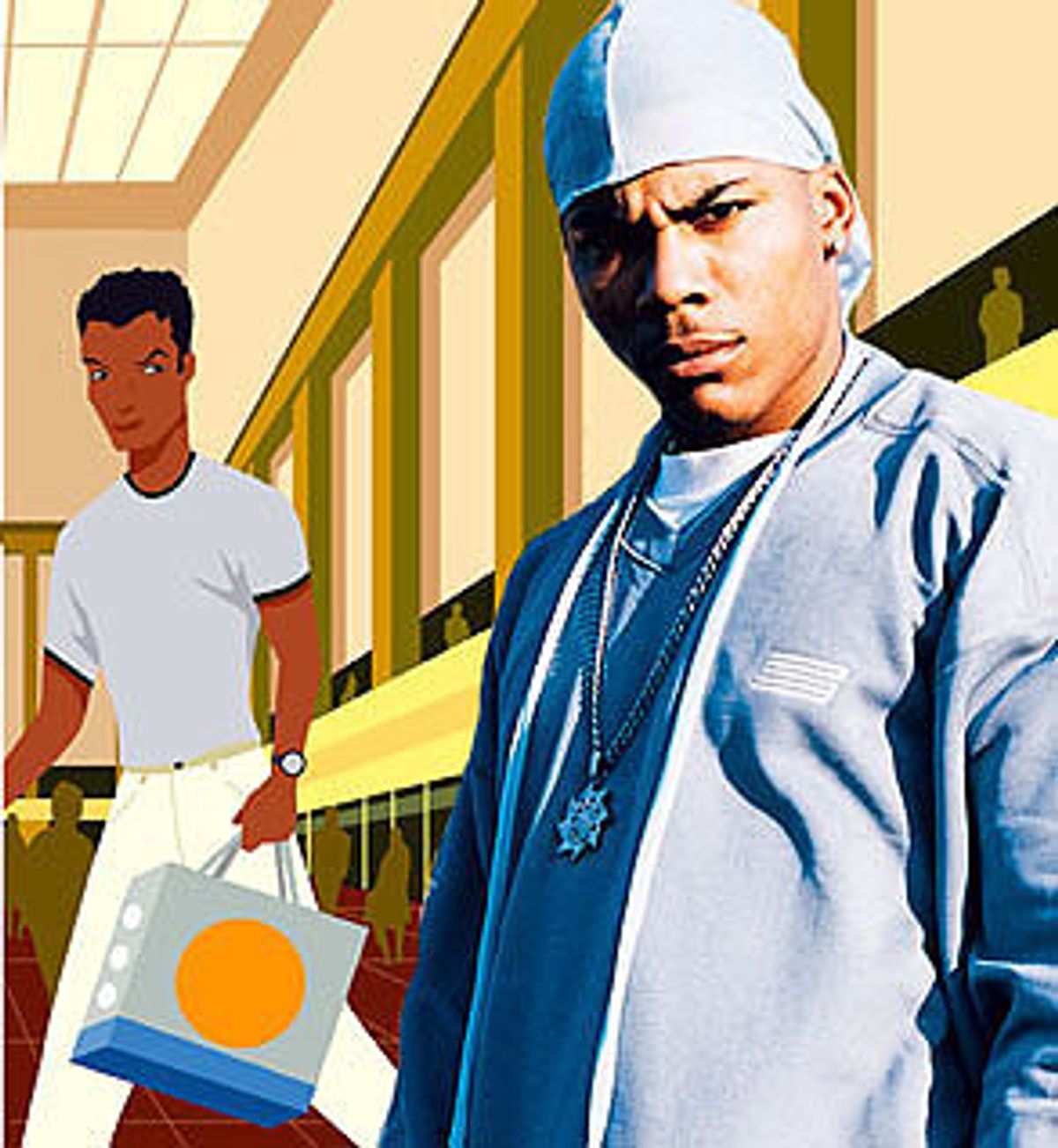

In late April, the rap star Nelly entered the Union Station Mall in his hometown of St. Louis to purchase 20 Cardinals jerseys for a video he was shooting at Busch stadium. Nelly (given name, Cornelius Haynes Jr.) is a local celebrity whose presence is usually welcomed. But on this day he was asked to leave by the Union Station security staff. The reason? He was wearing a do-rag, which is explicitly prohibited under the Union Station dress code as an item of "commonly known gang-related paraphernalia" -- a category the mall defines as "including, but not limited to: wearing or showing a bandana or do rag of any color, a hat tilted or turned to the side, a single sleeve or pant leg pulled/rolled up and flashing gang signs."

It's hard to believe that a rapper whose Grammy-winning "Country Grammar" album sold more than 8 million copies and put St. Louis on the hip-hop map would head down to Union Station Mall to engage in "gang-related" activity. But in this mall, as in many others across America, one doesn't have to be a gang member to be evicted under anti-gang ordinances; one merely has to dress in a way that makes one look like a gang member, as defined by the mall in question.

The mall, insist mall operators, is private property, and as such, its owners can make any rules they like without consideration of their patrons' constitutional right to free speech. Dress codes, which they claim are based on profiles of gang paraphernalia provided by local police departments and the FBI, are created, they say, as safety measures, not, as one critic of the Union Station Mall insists, as a thinly disguised method of "ethnic cleansing."

A familiar question arises: Do clothes make the man? In this case, a legal query follows: Do clothes make the man dangerous? After decades in which so-called gangster fashion has borrowed from and infused the mainstream, we have entered an age in which kids imitate hip-hop stars imitating gangsters who often imitate gangsta rappers (who may or may not have anything to do with real gangsters). At this point, it is nearly impossible to say whether a particular item of apparel signifies anything at all. "Gang-related" clothing can look very much like clothing favored by African-American youth and the kids of all races who have picked up on the popularity of hip-hop fashion. It also can be the clothes of a someone ready to pick a fight at the mall.

So when is a fashion victim a security risk? The mall owners say that on their turf, they get to decide. But a growing number of complaints and lawsuits have been filed -- by activist groups, the ACLU and individuals -- that challenge the claim that malls are private. Even if a mall is considered private, with the same rights as entities like stores and restaurants, its owners cannot enforce rules that result in racial discrimination.

But the battle is not only legal, it is cultural as well: Even if a mall defends itself legally against a lawsuit, being publicly accused of racism can be a public relations disaster, not to mention economic suicide for a retail outlet whose profits depend on the goodwill of its community. Yet a mall can expect a similar dive in revenue if patrons are too afraid of potential violence to shop there.

In St. Louis, on the day after Nelly was asked to leave Union Station Mall, the local chapter of the National Action Network (NAN), an African-American activist network whose national chairman is the Rev. Al Sharpton, issued a "travel advisory" warning black shoppers to stay away from Union Station. The group has staged two protests so far -- the first on May 7, followed by a second on May 20 -- led by the Rev. Horace Sheffield III of the Michigan NAN, and Lizz Brown, a local radio personality. About 150 people, many wearing bandanas and do-rags, marched through the mall to protest the so-called anti-gang dress code, which they claim is really an "anti-black" dress code designed to keep African-Americans out of the mall.

And on the day of the first protest, Brown, later quoted by the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, explicitly equated the dress code with pre-civil rights racial segregation: "Years ago this station had a sign outside that said, Whites Only," she said. "They took down the sign, but they continued the policy."

For its part, the Union Station management team claims in a recent press release that the policy is enforced without regard to "age, race, or economic standing." They stop anyone -- black, white, Asian, Latino, or famous musician -- who violates the dress code, which the mall operators say was adopted after a security consultation with the St. Louis Police Department and the FBI. So far, said mall spokesperson Jennifer Jones, the code has resulted in an 11 percent increase in retail sales.

But Sheffield believes that whatever gains have been made by Union Station have come at the cost of its African-American customers. "The overall issue is that when you have urban gentrification, it often takes the form of ethnic cleansing," he says. "They want to homogenize the space so that white upper-class patrons feel comfortable, by getting rid of the African-American patrons who frequented their businesses when times were bad."

Whether malls are private or "quasi private-public" entities is the focus of much debate. In 1972, the Supreme Court ruled in Lloyd vs. Tanner that shopping centers were considered private entities, and could therefore limit speech activities on their premises. But in a case eight years later, the court ruled that states could grant greater free-speech rights than those in the Constitution. The Supreme Court has not since ruled on a case that would overturn Lloyd vs. Tanner; but many state lawsuits over the past few years have attempted -- sometimes successfully -- to redefine shopping malls and restaurants as public spaces governed by constitutional law.

Denise Lieberman, legal director for the Missouri ACLU (which has not yet taken up the Union Station case), says there is an argument to be made that malls are the modern-day equivalent of town squares -- places where all members of the community can gather. That argument may be bolstered by the fact that malls often advertise themselves as public spaces where the whole community can shop, eat and be entertained.

According to Lieberman and others at the ACLU, the presence of government offices -- like a city police substation, or a post office -- or the use of public funds for infrastructure in the building of a mall, also leaves shopping malls open to lawsuits alleging that they fail to grant patrons the right to free speech.

In fact, in 1998, the Missouri ACLU successfully secured a $40,000 settlement for an African-American teenager who claimed to have been illegally detained for more than two hours by security staff at the Northwest Plaza Shopping Center for violating an unwritten dress code by wearing a bandana around his leg. As part of the settlement, the mall also agreed to dismiss charges against 19 other shoppers who had been detained for dress code violations.

But other state courts have ruled that shopping malls are under no obligation to uphold free speech. The Minnesota Supreme Court upheld the Mall of America's right to limit the speech of animal rights protesters this March, deeming the use of government money to build the mall's infrastructure to be "irrelevant."

Many more similar cases are pending. In New Mexico, the SWOP (Southwest Organizing Project) and the ACLU have filed a suit against three local malls, seeking to have dress codes abolished and to secure the right to picket and leaflet on mall property. These groups argue that the mall, which rents space to government agencies for public services such as voting booths and motor vehicle department offices, is a public entity.

It now appears that the NAN coalition will prepare a similar case against the Union Station Mall. Sheffield says that in their lawsuit they will argue that the Union Station Mall has received government funds but has failed to protect the First Amendment rights of its patrons.

But even private entities are not allowed to discriminate against patrons on the basis of race, and any group that can prove that a private entity is practicing systematic racial discrimination is likely to win in court, regardless of the company's status as a public or private entity.

One such case is pending against Dick Clark's Restaurants Inc., alleging that the management of one restaurant, located in a Philadelphia mall, attempted to get rid of African-American clientele (whom management allegedly referred to as the "Norristown element") by firing black security guards, banning hip-hop music, raising drink prices, and enforcing a dress code -- no baseball caps, football jerseys or Timberland boots -- that prohibited fashions popular with local African-American youth.

Lawyers representing the fired security guards say that when they sent black and white customers into the restaurant, all of them dressed in apparel that violated the dress code, only the African-Americans were asked to leave. "We sent investigators in there, Caucasians, dressed in violation of the code, and nobody bothered them," attorney Robert Adshead told the Philadephia Inquirer. "One sat under the sign that said what you couldn't wear, and he was waited on the whole night."

The claim by Union Station Mall management, and the operators of other malls across the country, that they enforce dress codes without regard to age or race, could be difficult to defend. "Whenever you build a profile on a person's appearance, rather than their actions, you are in slippery territory," says the ACLU's Lieberman. "If your profile of appearance is skewed towards a cultural or a racial group, then that is racial profiling."

But if the appearance of patrons is designed to imitate gang-bangers, and gang activity is what the mall seeks to eliminate, crisp debate quickly devolves into subjective sparring. Not only does the definition of "gang-related" clothing appear to differ from mall to mall, the willingness of management to talk about dress codes varies wildly. Some malls claim to have no rules but refuse to confirm the lack of rules. Some mall representatives say they don't know if they have rules and don't know how to find out if they do or not. Many malls have rules but refuse to describe them.

Told of the list of attire prohibited at Union Station Mall, Monica Davis, marketing manager for the Mall of America in Bloomington, Minn., says, "Holy cow, we don't have anything like that here!" There are some rules, she says -- minors under the age of 15 must be accompanied by an adult on Friday and Saturday nights -- but the only item of clothing banned in the mall are masks, which are prohibited by a Bloomington city ordinance. "We react or respond to conduct, not dress," says Davis, though she admits that gang violence in the mall and the outlying community is rarely a problem. "You can tell the rappers that they are welcome to come here."

Managers at a handful of other malls were not as forthcoming as Davis. For the most part, they were uncomfortable explicitly stating policies on dress and how their security staffs identify potentially disruptive customers. For comparison, I called about a dozen malls across the country, randomly selected for geography (both coasts and the Midwest), location (urban and suburban), the affluence of the surrounding community (I also looked to see if their flagship stores were say, Saks and Neiman Marcus, or J.C. Penney and Sears) and their proximity to areas with frequent reported gang activity.

At the Beverly Center, an upscale mall located in Beverly Hills, a spokewoman expressed shock at the inclusiveness of the Union Station dress code. She said that she had never heard of anything like that at the Beverly Center, but she passed me on to public relations. Public relations refused to comment without first obtaining permission from the marketing department (who later passed me back to public relations). So there aren't any publicly posted guidelines for conduct or dress? I asked. "I can't comment on that."

Eventually, I was allowed to speak with Mary Beth Bartlett, the head of Beverly Center security, who told me that the only dress code at Beverly Center is that shoes and shirts must be worn at all times. "Everything else is welcome," she said. "We react specifically to behavior, not dress, and we absolutely do not profile our customers based on their clothing."

The security guard at Tanforan Plaza in San Bruno, a suburb outside San Francisco (whose flagship stores are J.C. Penney, Target and Sears) also expressed shock at the wide range of the Union Station policy. At Tanforan there is an anti-gang policy, but it is more limited: You can't congregate in groups larger than three, and you can't "show off your colors," which the guard defined as having a red or blue bandana, or a colored belt that hangs off the pants.

"But we won't just stop anyone," she said. "They have to look gang related." How does one know if a patron is gang related? "We know," she said. "The gangs in San Bruno have been here forever. We're very familiar with them." You mean you recognize their faces? Yes, she said. When I asked for her name, however, she said she couldn't give it to me.

Defenders of dress codes like to give the impression that their codes are based on science. Many, like the Union Station Mall, claim that their profiles of potential gang members come straight from local law enforcement and the FBI. But if there are such profiles, the FBI is not aware of it.

Ken Neu, acting section director of the Violent Crime and Major Offenders Division at FBI headquarters, says that he is not aware that the FBI has published profiles for public dissemination. "If they are saying they got this information from the FBI, they probably mean that we may have taught a class or a symposium for local law enforcement," says Neu.

Gang members who wish to advertise their affiliation do so in incredibly specific ways, and it would be next to impossible to compile a general profile that is relevant in every region, says Neu. And, as others have pointed out, gangster fashion goes through brief cycles -- once gang members invent a style, it is quickly adopted by the mainstream, and the actual gang members move on to a new innovation, starting the cycle all over again.

Teenage boys are the group most often stopped for dress code violations in malls, but Neu warns, "It's important not to confuse gang activity with juvenile delinquency. They are not the same thing. While there are often a few juveniles affiliated with a gang, the vast majority of gang members in the United States are not juveniles."

Still, the danger from actual gang members is real, says Neu. "If you know you have two rival gangs in the neighborhood, you don't want them to re-enact "West Side Story" in the middle of your mall."

But it is really only the gang members themselves, and specialized law enforcement units assigned to keep track of them, who are most fluent in the code of the street. They may certainly react in a violent way to a rival gang's signature styles, but those signs often are so subtle that they can be decoded only by other gangsters. In this way, dress codes may only speed up the gangster fashion cycle. Ban bandanas, and they'll start tilting caps; ban caps and they'll start pushing up sleeves and pant legs -- the sartorial possibilities are endless, and the end of the cycle is nowhere in sight.

Which may be one reason that, while malls like Union Station and others are busy kicking out shoppers for "gang-related" clothing, some other urban malls take it for granted that their customers will not only dress like gangsters, but will also actually be gangsters. A Nexis search for mall dress codes over the past decade turned up several stories of malls, many located in areas with a fairly high level of gang activity, who have given up trying to police clothing and have gone back to simply policing conduct -- even in response to actual gang violence in their mall.

In 1994, after a gang-related shooting at a mall in Fort Worth, Texas, the owners of several Tarrant County malls considered adopting an anti-gang dress code, but at least one director of public safety at those malls said that they dropped the code after five months, because it was impossible to distinguish between teens emulating gangster fashion, and actual gang members.

Interestingly, the confusion of mall managers, who insist that they are trying to protect patrons and profits, appears to be something that rapper Nelly understands. So far, he has refused to take part in the protest against Union Station. Through his publicist, Jane Higgins, he has said that he does not consider his treatment at the hands of Union Station security to have been racially motivated.

This equanimity has angered those who protested Nelly's eviction from the mall -- so much so that some have even called for a boycott of his music. Sheffield does not personally support the Nelly boycott, though he does feel that, as a role model for African-American youth, Nelly should stand up for their right to wear the fashions that he inspires.

"He was kicked out of the mall for his choice of apparel," says Sheffield, "a kind of apparel that kids will choose to emulate because they see him wearing it, and may have to suffer the same consequences. He has a responsibility, if he is encouraging this kind of dress, to stand up against this policy."

But responsibility is the crux of the whole argument -- the responsibility of the mall to protect its patrons and tenants; the responsibility of the protesters and their lawyers to protect the Constitution and its tenets.

It's possible that the best way to minimize the security risk and maximize the rights of customers and the profits of the malls is to ignore clothes and focus on conduct. Such a policy has been successful -- not just for malls in areas far from gang territory, but for some in the middle of it.

For example, after rival gang members opened fire on each other in a West Covina, Calif., shopping mall in 1992, representatives from various nearby malls told the L.A. Times that it didn't make sense to ban known gang members from their malls after the incident -- unless they were explicitly seen engaging in criminal activity.

"If they're walking through the mall -- just that alone is not going to cause us to bother them," said Glendale Police Sgt. Matt Wojnarowski, who worked in the police substation at the Glendale Galleria. "They need to buy clothes, too."

Shares