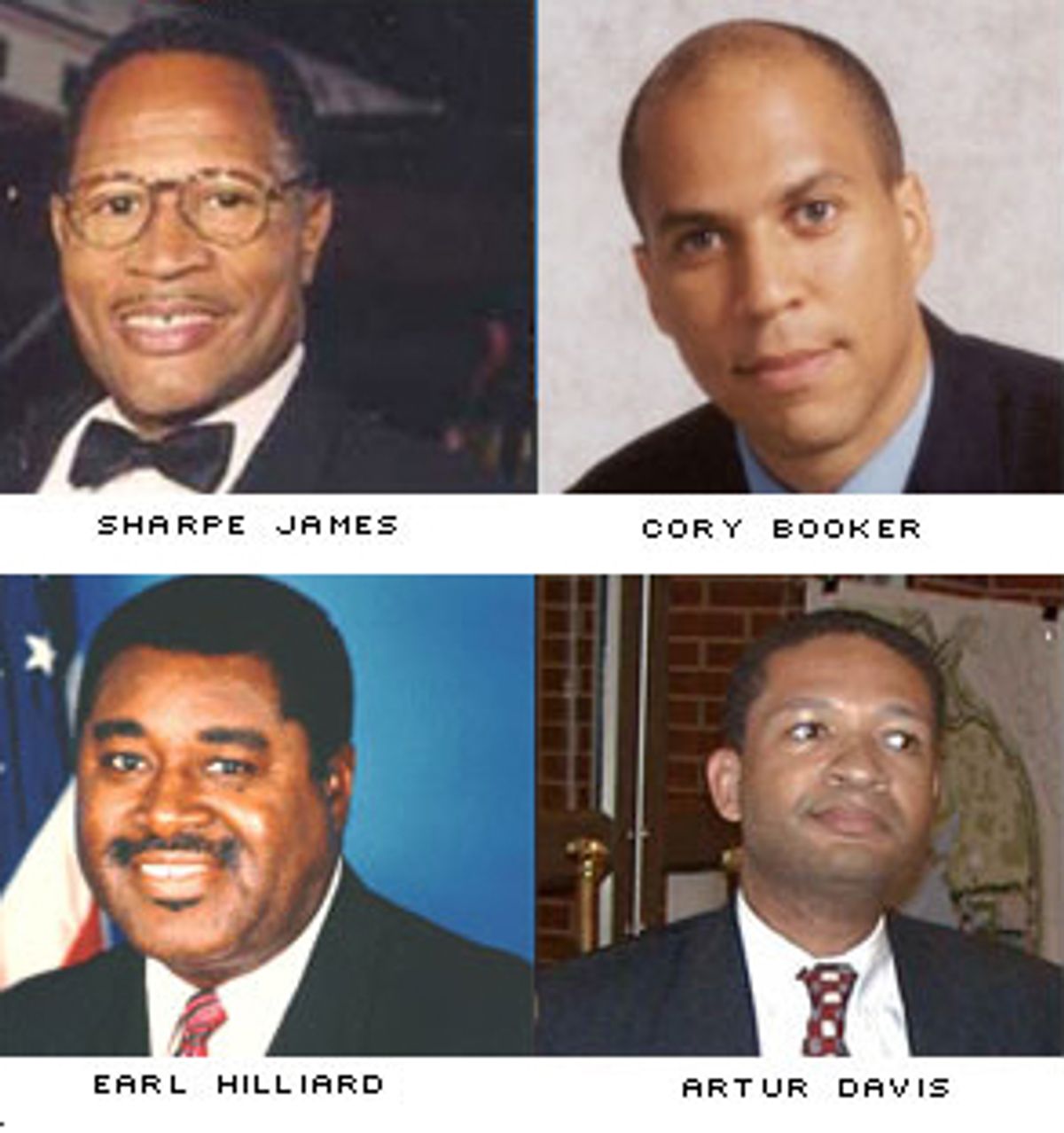

Newark (N.J.) City Councilman Cory Booker got the message pretty quickly. Mayor Sharpe James wasn't pleased that the young go-getter was going to challenge him, and told him privately that he would beat him with one simple strategy.

"I'm going to out-nigger you in the community," James told Booker, according to a source close to Booker.

Booker wouldn't comment about that story, and James could not be reached for his version of events. But that tactic does appear to be a key way James secured his victory, and won his fifth term as mayor last month, by a 53 to 46 percent margin.

With apparent sincerity, Booker still forces himself to remain respectful of his opponent. "I'm the beneficiary of a legacy of struggle," says Booker, "of the people who bled the beaches of Normandy red for me, of the people who bled the Southern soil. Martin Luther King and that generation --- including Sharpe James, that generation -- I am the product of that generation."

Like Booker, young African-American candidates have benefited from the trailblazing of older black leaders in very tangible ways: They're better educated, live in a more integrated society and attract myriad white supporters. They've grown up in a more colorblind society. But when they challenge their graying predecessors -- most glaringly, James and Rep. Earl Hilliard, D-Ala., who is fending off a serious primary challenge from Artur Davis, 34 -- these very opportunities are held against them. And suddenly, their loyalty to their own race comes under fire.

Even if the tactics aren't quite Sheriff Bull Connor-level, one can't help but contemplate the outcry had James and his army of patronage hacks been a lighter shade of pale. On election day in Newark, for instance, federal election monitors responded to reports that Newark police officers had been trying "to influence people to vote a certain way," according to U.S. Attorney Christopher Christie. The Web site PoliticsNJ.com reported that the police officers told voters to "do the right thing" by supporting James. When it comes to relinquishing power and fiefdoms, entrenched black incumbents are no more interested in surrendering than the bigoted white bullies whose corrupted kingdoms they helped topple decades ago.

These new candidates are not simply different politicians, they represent a larger zeitgeist shift among politically active African-Americans. According to a study published last year by the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies, a think tank focused on American minorities, there are substantial philosophical differences between the new and old generations of black leaders. Younger black elected officials "more strongly support school vouchers, are less positive toward the federal government and more in favor of devolution, are more supportive of the partial privatization of Social Security, are more pro-business," and are also three times less likely to consider "racism" the most important national problem.

Those qualities certainly seem to apply to Booker, who has praised school vouchers and found support across the river with the free-marketeers at the conservative Manhattan Institute. And while Davis says that he opposes school vouchers and some of the other more center-right positions Booker has flirted with, he does say that "I think certainly that I am of the New Democrat mold and Earl Hilliard is of a more conventional mold."

Younger black candidates are more likely to be politically independent (11 percent, compared to 7 percent of older officials), and less likely to be Democrats (69 percent, compared to 77 percent). "This is the same pattern found in the black population," Bositis writes, "where younger people (18-35 years) were more independent (28 percent) and less Democratic (62 percent) than black seniors (13 percent independent, 79 percent Democratic)."

Obviously these differences stem from different life experiences. Most older black elected officials attended segregated high schools and were twice as likely to have attended a historically black college than their younger counterparts. "The Sharpe James-Cory Booker race was almost an ideal representation of what's going on in the generational change that I studied and wrote about," says David Bositis, senior policy analyst at the Joint Center.

Equally instructive is the current face-off between the entrenched and ethically challenged Hilliard and Davis, a graduate of Harvard Law School who worked for the United States attorney's office -- credentials that would seem unimpeachable. A smart guy on the side of the law. But not to Hilliard.

"The only thing he's done for black people is put them in jail," Hilliard has said of Davis.

So a résumé that includes a law practice focused on criminal defense and workplace discrimination, a clerkship for Alabama federal Judge Myron Thompson (an African-American) and even an internship at the Southern Poverty Law Center is ignored so that Hilliard can actually criticize Davis for serving as an assistant U.S. attorney, where he prosecuted drug dealers.

(Not to mention the argument that prosecuting black drug dealers helps the black community, seemingly lost on those with Hilliard's view of the world.)

But that was nothing compared to a live TV interview on May 30, when Hilliard charged that Davis was forced to resign as a federal prosecutor "because of a date-rape charge."

Davis says he was "not surprised" by Hilliard's low blow, and believes the tactic backfired this time. After Hilliard made the charge, Davis' former boss, former U.S. Attorney Redding Pitt, now the state Democratic Party chairman, told the Birmingham News that there was "absolutely no basis" to Hilliard's charge. Davis says his campaign's polling numbers "showed that we surged dramatically after he said that."

"That's Earl Hilliard's pattern," Davis says. "Ten years ago Earl Hilliard put out racist fliers against a black opponent. Power is not surrendered easily."

Hilliard would not return calls for this story.

Davis' campaign against Hilliard in 2000 ended with Hilliard trouncing Davis, 58 percent to 34 percent. Two weeks ago, Davis had a strong enough finish in the primary, 43 percent to Hilliard's 44 percent, that he forced a runoff and the two will face each other again at the ballot box on June 25.

In some ways, Davis seems self-conscious about taking on a member of the revered old guard. "What we have tried to do is make the case that we are not challenging the civil rights generation, or questioning the civil rights movement," Davis says. "My candidacy and campaign are the products of the civil rights movement."

Hilliard, of course, blazed a trail in his first election to the U.S. House, in 1992, by becoming the first African-American to represent Alabama in that office since the 19th century. "It's no longer enough to be the first black elected since Reconstruction," Davis says. "Now it sets a high historical burden -- one that I honor but also one that I believe should obligate you to be a leader, to be one of the more effective and dynamic members of Congress." But on the contrary, Davis says, Hilliard has been among the least effective.

To say the least. Davis has no problem rattling off a list of Hilliard's ethics shenanigans. "He had unpaid taxes for a period of time. He was diverting county money to organizations that may or may not exist. He was diverting campaign money for personal use, and he was accused of misleading the House Ethics Committee about that. He has a wonderful penchant for getting into trouble." And unlike his bogus rape allegation, Hilliard's offenses have all been extensively documented.

As with Booker, the support Davis has been able to generate from "New" Democrats, many of whom are Jewish, has been used against him. At a political convention in April, someone distributed a flier about "Davis and the Jews," not surprisingly a combination described as "No Good for the Black Belt."

"Mr. Davis must simply understand that Jews the world over have never come to the aid of black or dark skin people because it was the right thing to do," the flier reads. "If the current invasions, murder and abuse within the Palestinian territory sound familiar, its only because in the not to distant past we seen the apartheid do exactly the same in the black villages of South Africa with Israel's support."

The sheet was signed, "By friends to re-elect Earl Hillard for Congress in the seven congressional district." Hilliard said he knew nothing about the flier, and accused Davis of generating it himself to drum up further Jewish support.

In this, James and Hilliard have more in common than do their respective opponents.

James "ran a campaign trying to appeal to people's fears, to their lesser angels," Booker says in an interview with Salon. "He ran a campaign trying to divide and conquer."

Booker, raised in nearby Bergen County, educated at Stanford, Yale Law School and Oxford as a Rhodes scholar, wasn't authentically black, James would declare. "You have to learn to be an African-American, and we don't have time to train you," James shouted, as if at Booker, at one rally. His campaign slogan became "The Real Deal." The usual race-baiting hucksters, like Rev. Jesse Jackson and Rev. Al Sharpton, came out to beat their usual drums. Jackson said Booker -- who worked on Jackson's 1988 presidential campaign -- has a "sheeplike appearance and wolflike characteristics."

What wolflike characteristics? Booker was, of course, a tool -- a way for whitey to get his meat hooks into Newark. James even accused Booker of taking campaign contributions from the Ku Klux Klan.

"This is about taking over Newark for power," James told a small crowd in early May, roughly two weeks before the election. "The people who left Newark could never believe we'd still be here. So they're sending someone in to take it over. They sent someone who acts like us, talks like us but is not us. They want Newark! They want our port! They want Newark Airport! They want our city! They want to cut down Sharpe!"

Booker tells Salon that James used "race-based appeals while we talked about real things." Like the low rate of minority-owned businesses in Newark, or the fact that nearly 90 percent of the city's municipal contracts go to firms outside the city. "He played to the fears; we talked about the real stuff, including issues that do have racial realities. Like the disparities in incarceration in New Jersey, which is worse than in Alabama, or Mississippi."

Like Hilliard, James had a less-than-stellar record that Booker could exploit, including a federal corruption investigation that ended with the conviction of James' chief of staff for embezzlement and his police director for bribery. And the fact that James, who drives a Rolls-Royce, has seen his salary go from $80,000 when he was first elected in 1986 to $248,000 today -- more than any governor, not to mention the mayors of New York City, Los Angeles and Chicago. More than one-quarter of the good citizens of Newark, not incidentally, live in poverty.

Booker was elected to city council in 1998 and almost immediately James started hearing his footsteps. The reaction was, sadly, typical for any entrenched hack, regardless of color. In the summer of 1999, for instance, Booker staged a 10-day fast and sit-in at the blighted Garden Spires housing complex in Newark to call attention to the community's problems. James had already been eyeing Booker warily, thinking him a media hog, and James' police chief announced that he wouldn't provide police protection for Booker and his supporters during their protest. (Eventually city officials were shamed into action and announced that they would provide the projects with a 24-hour police van and a security fence.)

In November 1999, Booker led a two-day march to draw attention to the kids of Newark and their high rates of teen pregnancy, dropoutism and infant mortality; City Hall officials initially denied Booker a permit for his march.

Then, during the May 14 mayoral primary election, city employees, including police officers, reportedly harassed Booker supporters at the polls. This after a campaign where a Booker campaign trailer was broken into and files were stolen, and one of James' closest aides was arrested for tearing down Booker's campaign signs.

During the campaign, it wasn't enough for James to slam Booker for his past support of school vouchers, for the support he had gleaned from suspect boosters (at least inside Newark) like George F. Will and Jack Kemp. While whisper campaigns slimed Booker for being gay, Jewish and white, James himself accused Booker of taking money from the Ku Klux Klan and Booker insists that James called him "the faggot white boy." (James has denied saying it.) Last August, a Booker supporter told the New Jersey Jewish News that he heard James accuse Booker of "collaborating" with Rabbi Shmuley Boteach -- a friend of Booker's from his Oxford days -- "and the Jews to take over Newark."

"I was not surprised by anything," Booker tells Salon. "I knew what I was going up against. I knew the exact attack."

Booker-James and Hilliard-Davis are but two races, and there are of course stark differences in addition to the similarities. Booker is more New Democrat than Davis, whose primary differences with Hilliard are over policy in the Middle East (Davis supports Israel while Hilliard is more supportive of the Arab world) and whether or not Hilliard is, well, a total disgrace. But the young guns also more likely represent races of Election Day future.

"This is a race between traditional political machines and more independent voters," says Davis, who says that in his district the Hilliard-backing machine has "steadily withered" over the last four election cycles. "We're entering a phase when black voters will be more independent-minded," he says, repeating the conclusions of the Joint Center's study.

In that sense, some previous races with similar dynamics may show both the promise and the limitations of this changing of the guard. In 1994, two entrenched and somewhat wanting black incumbent congressmen were successfully challenged by young black pols. Houston City Councilwoman Sheila Jackson Lee beat Rep. Craig Washington, D-Texas, and while Lee has proved to be more pro-business and a bit more mainstream than her predecessor, she too has become a source of some controversy, being chauffeured by a staffer from her home every morning to the Capitol one block away, having temper tantrums on flights when her various needs weren't met, tearing through and using up staffers like a flu patient with a box of Kleenex.

That same year in Philadelphia, however, then-state Sen. Chaka Fattah, 36, felled 62-year-old Rep. Lucien "The Solution" Blackwell, D-Penn., in the primary. Blackwell was propped up by the entire city power structure -- then-Mayor Ed Rendell and then-City Council president (and current mayor) John Street included. But Fattah won, becoming one of the more impressive liberal voices in Congress in the process, developing a real leadership role on education issues and demonstrating an ability to reach across the aisle and find common ground with conservative Republicans.

And in Georgia right now, Democratic Rep. Cynthia McKinney is facing a surprisingly strong contest in her primary from former state Judge Denise Majette. This is no generational challenge; both women are in their 40s. But McKinney -- who seemed to insinuate that the Bush administration allowed Sept. 11 to happen so its corporate buddies could subsequently make money -- belongs to a somewhat discredited old school of firebrand, and factually challenged, politics.

She's also seemed to go out of her way to stoke her constituents' paranoia of a Jewish conspiracy. Like Hilliard, McKinney has taken a controversial approach to the Middle East conflict, hiring as her press secretary a man who had worked for two organizations reportedly linked to the terrorist group Hamas. (He later resigned after writing a letter to a Capitol Hill newspaper calling it "disturbing" that Jewish members of Congress "sit on the House International Relations Committee despite the obvious conflict of interest that their emotional attachments to Israel cause ... The Israeli occupation of all territories must end, including Congress.") After Mayor Rudy Giuliani turned down the $10 million check from Saudi Prince Alwaleed bin Talal after the prince suggested the United States rethink its support for Israel, McKinney generously offered to take the check to fund various black causes.

The Atlanta Business Chronicle recently wrote that "Majette is seen as closer to the new type of African-American leadership that is emerging nationally -- liberal but more inclined to form coalitions. Like other emerging African-American leaders, she is conscious of the emerging African-American middle class in the suburbs, long ignored by McKinney ... It will be a referendum on [the incumbent] and her brand of politics. Voters will decide if they want a flamboyant representative who makes headlines for opposing sanctions in Iraq or one who makes headlines for bringing services into the community."

And McKinney has responded somewhat predictably to her new challenger, painting Majette as -- you guessed it -- a tool of whitey. "Denise Majette's candidacy is a Trojan Horse for the good old boys from the bad old days," one of McKinney's campaign statements recently proclaimed.

Booker asserts that his race, and similar ones, indicate that black politics are, in the end, just like everyone else's. "Every ethnic group in every political system tries to resist change," he says. "From Congress all the way down to local government, incumbents have power. Go back and read the Federalist Papers -- the system is designed not to resist change." He quotes Frederick Douglass, who said, "Power concedes nothing without a demand."

There has been some tension between the Democratic House leadership and the Congressional Black Caucus over how much money should be directed toward Hilliard for his primary race against Davis. But for the most part, Davis has seen civil rights heroes like Rep. John Lewis, D-Ga., campaign for his opponent despite Hilliard's ethical problems. And Booker saw himself slammed by not only the usual race-baiters like Jesse Jackson and Al Sharpton, but by every major politician in New Jersey -- including Democratic Sens. Bob Torricelli and Jon Corzine, and Gov. James McGreevey, who told voters that if they reelected James, Newark would get a stadium for the state's pro NHL and NBA teams. "Newark, you give me Sharpe James, you get the Devils and Nets!"

After James was elected, those plans seemed to go the way of the Nets' NBA championship hopes. The question for the Democratic Party is how much longer it will keep attaching itself to related, similarly empty promises.

Shares